Abstract

Septic complications after coronary stenting are extremely rare. The occurrence of cardiac related sepsis after rapamycin eluting stent deployment has not been previously reported. The potential role of drug eluting stents in locally blunting the innate response to bacterial agents is discussed.

Keywords: infection, rapamycin, stent

Septic complications after coronary stenting are extremely rare.1–3 The occurrence of cardiac related sepsis after rapamycin eluting stent deployment has not been previously reported. In this report we present a patient undergoing repeat coronary intervention with drug eluting stents for in-stent restenosis who eventually developed a cardiac related sepsis and died. The potential role of drug eluting stents in locally blunting the innate response to bacterial agents is discussed.

CASE REPORT

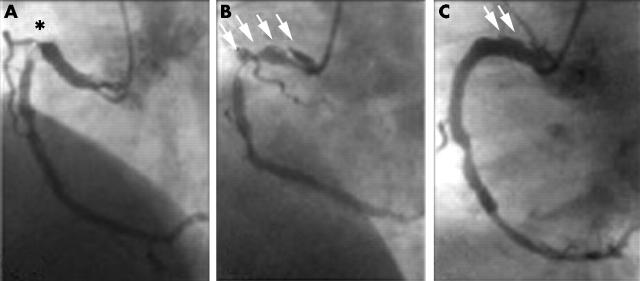

A 47 year old man was admitted for angina six months after bare metal coronary stenting. Angiography showed tight focal in-stent restenosis in the proximal right coronary artery. Two rapamycin eluting stents were successfully implanted to completely cover the target in-stent restenosis and to treat a balloon induced proximal coronary dissection (fig 1). The procedure, however, was cumbersome and prolonged because of vessel curvature and poor guiding catheter back up. After the intervention the patient remained asymptomatic and no changes in cardiac markers were detected. Two days later he started to have fever, chills, and malaise. Despite exhaustive screening for a potential source (including transthoracic echocardiography) no infectious focus was detected. Serial blood cultures yielded cloxacillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Oral cloxacillin was started but occasional febrile relapses occurred during the following week associated with progressive anaemia and C reactive protein rise. Intravenous cloxacillin and gentamicin were administered.

Figure 1.

(A) Severe focal in-stent restenosis on the proximal right coronary artery (asterisk). (B) A large dissection was induced after balloon dilatation of the lesion. The dissection (arrows) extended to the most proximal segment of the vessel. (C) Two rapamycin eluting stents were implanted to treat the in-stent restenosis (distal) and the proximal dissection. Small arrows indicate small persistent residual dissection at the end of the procedure.

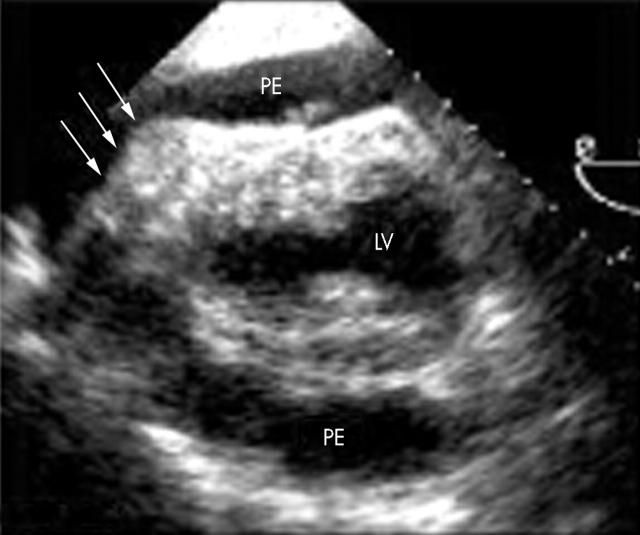

Transoesophageal echocardiography ruled out vegetations but showed a new severe pericardial effusion with echodense material overlying the right ventricular free wall (fig 2). Aortic wall or paracardiac abnormalities were not detected. Despite the lack of clinical sings of cardiac tamponade an urgent tap was performed to rule out pericardial empyema. The tap yielded 750 ml of yellowish pericardial fluid, which was an exudate, in which S aureus was cultivated. A watchful waiting strategy, with aggressive intravenous antibiotic treatment, was elected after surgical consultation. Residual pericardial effusion was ruled out by serial echocardiographic examination and the patient was discharged to the ward and allowed to be ambulatory. Two days later, however, he suddenly collapsed after a mild Valsalva manoeuvre. Electromechanical dissociation and recurrent cardiac tamponade were documented and pericardiocentesis yielded haemopericardium. Prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation was unsuccessful. A necropsy examination could not be obtained.

Figure 2.

Transoesophageal echocardiography showing severe pericardial effusion (PE) without evidence of chamber collapse and a fibrinous material (arrows) overlying the anterior wall of the right ventricle and the distal aspect of the left ventricle (LV).

DISCUSSION

Overt stent infection is exceedingly rare. Its diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and is often delayed.1–3 Pericardial effusion is often encountered in this setting. Visualisation of stent related abscesses or pseudoaneurysms has been reported with echocardiography and electron beam tomography.1–3 Disappearance of these abscesses has also been documented with conservative management and intravenous antibiotics.1 Although stent related cardiac sepsis was clearly seen in our patient the exact underlying pathological substrate (perhaps a ruptured coronary abscess) could not be defined. Recently, the ability of drug eluting stents to effectively prevent restenosis and to provide superb long term clinical results has generated enthusiasm.4 Rapamycin has potent antimigratory and antiproliferative effects and is a well known immunosuppressant drug. Studies in whole human blood suggest that therapeutic doses of rapamycin are associated with a dysregulation of the innate responses to bacterial infection and to an increased risk of hyperinflammation and sepsis by interfering with interleukin 10 gene transcription.5 Severe infections have also been reported recently in heart transplant recipients receiving tacrolimus and everolimus.6,7 Whether drug coating of stents may have a role in diminishing the local immunological response of the vessel wall remains to be determined.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rensing BJ, van Geuns J, Janssen M, et al. Stentocarditis. Circulation 2000;101:e188–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunter HU, Struup G, Volmar J, et al. Coronary stent implantation: infection and abscess with fatal outcome. Z Kardiol 1993;82:521–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu JC, Cziperle DJ, Kleinman B, et al. Coronary abscess: a complication of stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2003;58:69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, et al. A randomized comparison of sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jorgensen PF, Wang JE, Almlof M, et al. Sirolimus interferes with the innate response to bacterial products in human blood by attenuation of IL-10 production. Scand J Immunol 2001;53:184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisen HJ, Tuzcu EM, Dorent R, et al. Everolimus for the prevention of allograft rejection and vasculopathy in cardiac-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2003;349:847–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peraira JR, Segovia J, Arroyo R, et al. High incidence of severe infections in heart transplant recipients receiving tacrolimus. Transplant Proc 2003;35:1999–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]