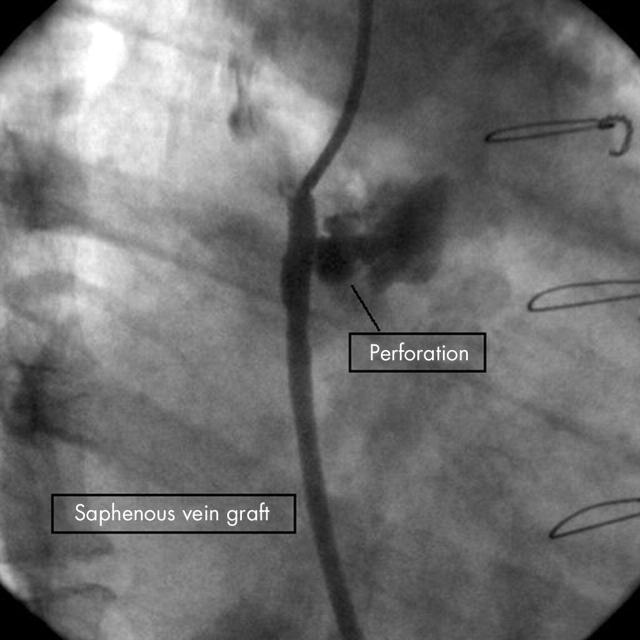

This figure is an angiographic image of a right coronary–saphenous vein graft (SVG) perforation following “post-dilatation” of a stent in the proximal graft. This rapidly led to pericardial tamponade requiring pericardial drainage and the deployment of a covered stent.

Vessel perforation following percutaneous coronary intervention is rare, occurring in 0.29–0.8% and is more often associated with atheroablative procedures. Progression to pericardial tamponade occurs in 31–46% of cases.

It is believed that prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) protects against progression to tamponade because of the presence of pericardial adhesions and the persistence of a pericardiotomy. In addition, proximal SVG segments may be thought to be extra-pericardial in location. This may be a misconception with anatomy texts confirming that “the pericardium fuses with the great vessels superiorly and may include the ascending aorta”.

Following surgery, the pericardium is sometimes repaired. This occurs more often when technically straightforward and in young patients where potential reoperation may be simplified if adhesions are minimised. This offers an appealing explanation but was not the case. More commonly the pericardium is left open forming a “pseudo-pericardial” space bounded by the pericardium laterally and posteriorly with the chest wall anterior. There is no mechanical boundary superiorly and this is the probable means by which extravasated blood was able to compress the cardiac chambers.

This case depicts a rare adverse outcome and makes the point that the mechanical effects of prior CABG do not eliminate the risk of tamponade following vessel perforation even in proximal SVG segments.