Abstract

Vocal vibrato and tremor are characterized by oscillations in voice fundamental frequency (F0). These oscillations may be sustained by a control loop within the auditory system. One component of the control loop is the pitch-shift reflex (PSR). The PSR is a closed loop negative feedback reflex that is triggered in response to discrepancies between intended and perceived pitch with a latency of ~ 100 ms. Consecutive compensatory reflexive responses lead to oscillations in pitch every ~200 ms, resulting in ~5-Hz modulation of F0. Pitch-shift reflexes were elicited experimentally in six subjects while they sustained /u/ vowels at a comfortable pitch and loudness. Auditory feedback was sinusoidally modulated at discrete integer frequencies (1 to 10 Hz) with ±25 cents amplitude. Modulated auditory feedback induced oscillations in voice F0 output of all subjects at rates consistent with vocal vibrato and tremor. Transfer functions revealed peak gains at 4 to 7 Hz in all subjects, with an average peak gain at 5 Hz. These gains occurred in the modulation frequency region where the voice output and auditory feedback signals were in phase. A control loop in the auditory system may sustain vocal vibrato and tremorlike oscillations in voice F0.

I. INTRODUCTION

Vocal vibrato and vocal tremor are characterized by the superimposition of frequency and amplitude oscillations on the voice signal. Rhythmic oscillations have been observed in the activity of laryngeal (Hsaoi et al., 1994; Koda and Ludlow, 1992; Niimi et al., 1988), respiratory (Rothenberg et al., 1988), and articulatory (Inbar and Eden, 1983; Sapir and Larson, 1993) muscles during vocal vibrato and tremor. The source of these oscillations is not well understood. It is believed that tremor may result from activity of a feedback control system associated with stretch receptors in muscles (Lippold, 1971), central oscillators, and ballistocardiograph, as well as from repetitive and asynchronous discharge of large motor units (Marsden, 1984). Winckel (1974) suggested that oscillatory muscle activity associated with vocal tremor and vocal vibrato arises from the activation of stretch receptors in laryngeal muscles. Recently, Titze et al. 002) presented a model of vocal vibrato in which vibratolike oscillations in voice fundamental frequency (F0) result from a negative feedback loop associated with stretch reflexes in pairs of antagonistic laryngeal muscles. While this model provides a persuasive explanation of how vocal vibrato is sustained, it does not account for a possible role for auditory feedback. Auditory feedback is known to play an important role in pitch and loudness control (Burnett et al., 1998; Jones and Munhall, 2000; Kawahara and Williams, 1996; Lane and Tranel, 1971). In the present study, we propose that reflexes in the auditory system contribute to sustaining frequency and intensity modulations in the voice signal in vocal vibrato and vocal tremor.

Vocal vibrato is characterized by periodic fluctuations in F0 and intensity in the singing voice. These pulsations typically occur at a rate of 4 to 7 Hz (Shipp and Izdebski, 1981) and with a F0 modulation extent of ±1 semitone (100 cents). Vocal vibrato is a desirable feature of singing as it gives richness to a tone (Seashore, 1938), helps to separate a singer’s voice from the orchestra (Sundberg, 1995), and makes vowels more prominent, allowing them to be more easily separated from background sounds (Marin and McAdams, 1991). The presence of vocal vibrato allows a listener to distinguish the voice of a trained singer from that of an untrained singer (Brown et al., 2000).

Like vocal vibrato, vocal tremor is characterized by pulsations in F0 and intensity (Koda and Ludlow, 1992). Pulsations in F0 occur at similar rates in vocal tremor and vibrato. Ramig and Shipp (1987) observed that the average rate of F0 oscillation was 6.8 Hz in vocal tremor and 5.5 Hz in vibrato. Shipp and Izdebski (1981) reported similar values with an average F0 oscillation rate of 5 to 6 Hz in vocal tremor and of 5.4 Hz in vibrato.

In addition to the acoustic similarities outlined above, vocal vibrato and vocal tremor share a similar pattern of muscle activation. An electromyographic (EMG) study of intrinsic (thryroarytenoid, cricothryoid, and posterior cricoarytenoid) and extrinsic (sternothyroid and thyrohyoid) laryngeal muscle activity in patients with vocal tremor found spectral peaks at rates of 4 to 5.2 Hz (Koda and Ludlow, 1992). Sapir and Larson (1993) observed spectral peaks at similar frequencies in the EMG signals of anterior suprahyoid muscles (geniohyoid and genioglossus) and extra-laryngeal muscles (thyrohyoid, strap, cricothyroid, and criocopharyngeal) in trained singers during vibrato. They reported that vibrato-related spectral peaks in EMG recordings occurred in these muscles at 4.83 Hz in a representative subject. Consistent with these observations, Hsaoi et al. 1994 reported modulations in cricothyroid activity as well as in thyroarytenoid muscle activity during vibrato.

The acoustic and EMG similarities between vocal vibrato and vocal tremor have led some researchers to speculate that these vocal features share common physiologic sources (Ramig and Shipp, 1987; Winckel, 1974). Ramig and Shipp (1987) speculated that a central generator produces tremor oscillations that are suppressed under normal circumstances. These oscillations are “released from suppression by disease,” resulting in a tremulous vocal quality. In contrast, these central oscillatory mechanisms can be “selectively recruited” to produce vocal vibrato (Ramig and Shipp, 1987, p. 166). Titze et al. 2002 proposed a model of vibrato in which oscillations in F0 result from the presence of “central oscillators” and “peripheral oscillators.” The term “central oscillators” refers to neural input to muscles that originates at the cortical level and generates oscillations in planned muscle activation (Titze et al., 2002). “Peripheral oscillators” refer to the biomechanical properties of the laryngeal system such as muscle mass and stiffness. These peripheral oscillators shape the oscillations in muscle activation generated by central oscillators (Titze, 1996; Titze et al., 2002). Titze and colleagues (Titze et al., 2002) described a “reflex resonance model of vibrato” in which a wide band of low-amplitude oscillations generated at the cortical level by central oscillations are shaped into a narrow band of oscillations through bi-directional negative feedback stretch reflexes. According to this model, the stretch reflex will generate oscillations at ~6 Hz.

Another factor that may contribute to the production of vocal vibrato is auditory feedback. Several studies have shown that auditory input influences the characteristics of vocal vibrato, suggesting that the auditory system may play a key role in regulating vibrato. Singers use auditory input to shape characteristics of vibrato such as rate and extent of modulation (Dejonckere, 1995; Deutsch and Clarkson, 1959; King and Horii, 1993; Vennard, 1967; Winckel, 1974). King and Horii (1993) reported that singers adjust their rate of vibrato to match a synthesized auditory signal presented at rates of 3 to 7 Hz. Deutsch and Clarkson (1959) observed that nonsingers decrease their rate and increase their extent of vibrato when producing vibrato under masking conditions. Also, Vennard (1967) noted that singers use auditory feedback to monitor the characteristics of their vibrato. When necessary, singers may fine-tune their vibrato by adjusting muscle activity. Winckel (1974) speculated that, during vibrato, the pitch and intensity of the voice signal might be adjusted continuously in response to auditory feedback. Thus, several studies support the suggestion that auditory feedback is capable of altering the characteristics of vocal vibrato.

Deutsch and Clarkson explored the relationship between the auditory system and vibrato oscillations (Deutsch and Clarkson, 1959; Clarkson and Deutsch, 1966). They proposed that vibrato results from a control loop within the auditory pathway that functions to maintain a steady note. Any unintended change in perceived pitch is corrected through compensatory adjustments in F0. Corrections in F0 are greater than necessary to return pitch to the desired level, causing the singer to systematically overshoot the desired pitch. Therefore, the singer must adjust pitch to compensate for the excessive correction. Again, the singer will overshoot the intended pitch. The singer will continue to adjust pitch towards the desired level and, in doing so, will overshoot the target pitch, resulting in continuous oscillations in pitch. According to Deutsch and Clarkson (1959), the frequency and extent of vibrato depends on the reaction time of the subject to an unintended change in pitch, the threshold necessary for an unintended pitch change to be detected and the rate at which an error can be corrected. Changing these factors will alter the characteristics of vibrato. They showed that delays in auditory feedback and decreases in the threshold for perception of a change in unintended pitch alter the frequency and amplitude of the frequency oscillations in untrained singers (Deutsch and Clarkson, 1959; Clarkson and Deutsch, 1966). However, in a review of the mechanisms underlying vocal vibrato, Sundberg (1987) noted that Shipp et al. 1984 questioned the role of auditory feedback in generating vocal vibrato in trained singers, as they reported that delayed auditory feedback (DAF) did not alter the characteristics of vocal vibrato. Given the conflicting findings regarding the effects of DAF on vocal vibrato, the role of auditory feedback in sustaining vibrato needs clarification.

In the present study, we sought to further demonstrate that properties of the auditory system sustain vibrato by experimentally eliciting pitch-shift reflex responses while subjects produced a steady tone. Previous studies revealed that subjects monitor their auditory feedback signal to regulate F0 when producing steady vowels (Jones and Munhall, 2000), glissandos (Burnett and Larson, 2002), continuous speech (Donath et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2002), and when reading (Laukkanen, 1994). Any deviation in pitch from the intended level is corrected through a compensatory reflex, termed the pitch-shift reflex (PSR) (Burnett et al., 1997). Like the stretch reflex, the PSR is a bi-directional negative feedback closed-loop reflex. When pitch is perceived to exceed the desired level, F0 is decreased. Conversely, when pitch is perceived to be lower than the desired level, F0 is increased. We propose that the PSR also contributes to the production of vocal vibrato.

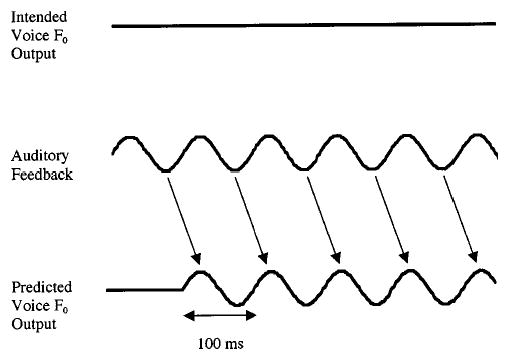

Many studies investigating the influence of auditory feedback on voice production explored the vocal response to a single, transient shift in auditory feedback (Burnett et al., 1997; Burnett and Larson, 2002; Donath et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2002). In the present study, we examined vocal responses to continuous sinusoidal modulation in auditory feedback. We hypothesized that responses to these modulations in auditory feedback (pitch-shift reflex) could sustain oscillations in voice F0. We further speculated that the pitch-shift reflex (PSR) could sustain oscillations in F0 with a period equal to twice the latency of the PSR. The latency of one PSR, causing either an increase or a decrease in F0, ranges from 100 to 150 ms (Burnett et al., 1998). This delay may represent the time needed for pitch decoding, error detection and motor command generation, transmission delays, and muscle contraction speed (Kawahara and Williams, 1996). The delay for one complete F0 cycle consisting of an increase and a decrease in pitch would correspond to two PSRs, or equivalently ~200 to 300 ms. Consecutive PSRs would generate cyclical oscillations in F0 with a period of ~200 to 300 ms or, equivalently, a natural frequency of response of ~3.3 to 5 Hz (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration depicting the proposed manner in which the pitch-shift reflex can sustain vibratolike oscillations in voice fundamental frequency (F0). The upper trace shows the intended F0 contour (intended voice F0 output). The middle trace shows perceived F0 when real time auditory feedback is sinusoidally modulated at 5 Hz (auditory feedback). The lower trace depicts the expected F0 signal in response to modulations in auditory feedback (predicted voice F0 output). Decreases in perceived F0 result in compensatory increases in voice F0 with a 100-ms delay. Arrows indicate F0 responses following perceived decreases in auditory feedback F0. Conversely, increases in perceived F0 result in compensatory decreases in voice F0 also with a 100-ms delay. Arrows indicating voice F0 responses corresponding to perceived increases in F0 are omitted for clarity.

II. METHODS

A. Subjects

Six subjects (five females and one male; mean age 27.5 years) with normal hearing and no history of speech, language, voice, or neurological deficits participated in this study. None of the subjects were trained singers and all were naïve to the purpose of this study.

B. Stimuli

Subjects were seated in a sound-treated booth and instructed to repeatedly sustain the /u/ vowel sound at a comfortable and steady pitch for approximately 5-s intervals at 70 dB SPL at a 5-cm microphone-to-mouth distance (self-monitored visually with a Dorrough Loudness Monitor model 40-A). Vocalizations were limited to 5-s periods to ensure that subjects did not vocalize using their expiratory residual capacity. Vocalizations were transduced using an AKG boom-held microphone (model HSC 200). The signals were amplified with a Mackie Mixer (model 1202), and then processed for pitch shifting using an Eventide Ultraharmonizer (SE 3000). The pitch-shifted feedback signals were routed through HP decibel attenuators (model 350D), amplified to 80 dB SPL by a Crown audio amplifier (D75-A), and fed back to the subject in near-real time (8–20-ms delay) via over-the-ear AKG headphones (model HSC 200). Air-conducted auditory feedback was amplified by approximately 10 dB to mask potential bone conducted feedback. The above equipment was calibrated with a Brüel and Kjær 2203 sound level meter (weighting A).

Sinusoidal pitch-modulations were introduced in the auditory feedback of each subject at a single discrete integer frequency from 1 to 10 Hz. Auditory feedback was modulated at only one frequency per condition, yielding a total of ten experimental conditions per subject. The extent of each sinusoidal modulation of auditory feedback was ±25 cents (100 cents=1 semitone), resulting in a peak-to-peak pitch modulation of 50 cents (0.5 semitones). The auditory feedback signal was modulated for the duration of each vocalization. A control condition was also collected for each subject, in which the auditory feedback signal was unmodulated. For each experimental condition, we analyzed voice output for a duration equivalent to 50 cycles of sinusoidally modulated auditory feedback. Thus, the rate of modulation of the auditory feedback signal determined the duration of the analysis window. For example, when a 1-Hz modulation was presented, 50 s of the voice signal were collected from 10 5-s vocalizations. Similarly, when a 10-Hz modulation of the auditory feedback signal was presented to the subject, 5 s of the voice signal were collected from one 5-s vocalization. As F0 was not modulated under the control condition, 50 s of the voice output were collected across 10 5-s vocalizations.

C. Data analysis

Voice output and auditory feedback signals were digitally recorded at a sampling rate of 10 kHz (5-kHz anti-aliasing filter) on a laboratory computer using MacLab Chart v3.5 A/D conversion software (AD Instruments). In off-line analyses (Igor Pro software, version 4.0 by Wavemetrics, Inc.), these signals were low-pass filtered at 200 Hz for female and at 100 Hz for the male subjects, differentiated, and then smoothed with a five-point binomial, sliding window to remove high-frequency components from the audio signals. Voice F0 was extracted from the preprocessed signals using a customized software algorithm in Igor Pro. The software algorithm detected positive-going threshold-voltage crossings, interpolated the time fraction between the two sample points that constituted each crossing, and calculated the reciprocal of the period defined by the center points. The resulting F0 signals were converted to cents using the following equation: cents=100 (39.86 log10(f2/f1)), where f1 is an arbitrary reference note at 195.997 Hz (G4) and f2 is the voice signal in Hertz. The conversion of signals to cents permitted a comparison of the extent of change in the F0 in response to a pitch modulation across all conditions regardless of baseline F0.

A long-time average power spectrum of physiologic tremor was derived for each subject from the voice output signal using discrete Fourier transformations (DFTs) on vocalizations in which auditory feedback was not modulated. Long-time average spectra for the voice output and auditory feedback were also obtained for each modulation condition using DFT. A resonance curve was derived for each subject by measuring the amount of energy present at a given frequency from 1 to 10 Hz following modulation at that frequency. Thus, the resonance curve is a composite curve obtained under ten experimental conditions.

Extent of oscillations in F0 was determined for each subject at the modulation frequency (between 4 and 7 Hz) in which the greatest spectral peak was observed in the resonance curve. Voice F0 output was band pass filtered between 1 and 20 Hz to remove extraneous noise from the waveforms, and averaged across a time window equivalent to two cycles of modulated feedback. Thus, duration of the averaging window varied according to the modulation frequency. The extent of F0 oscillations was measured from the averaged waveform as the difference in cents between the highest amplitude and the lowest amplitude peaks. Extent of oscillation was expressed as mean, range, and standard error of the mean (SEM).

Transfer functions of the audio-vocal system were constructed for each subject by comparing the extent and phase of the voice output to the modulated auditory feedback signals at all frequencies (1 to 10 Hz). To obtain a transfer function of gain (dB), the extent of voice F0 oscillations at a given frequency was divided by the extent of F0 modulations in the auditory feedback signal at that frequency. Similarly, the phase relationship between the voice output signal and the modulated auditory feedback signal was determined by subtracting the phase of voice output F0 oscillations from the phase of auditory feedback oscillations. A positive value would indicate that the voice output signal was phase-advanced relative to the modulated auditory feedback signal, while a negative value would suggest that the voice output signal was phase-lagged relative to the modulated auditory feedback signal. A zero value would indicate that the voice output and modulated auditory feedback signals were in-phase.

III. RESULTS

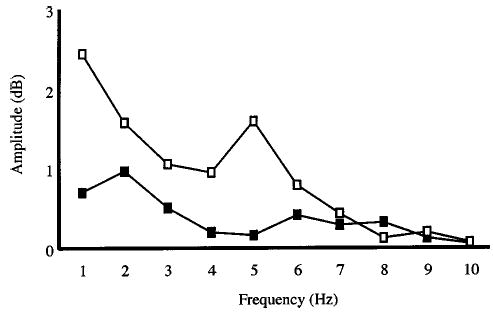

We compared the energy present in each subject’s voice signal at frequencies from 1 to 10 Hz under experimental and control conditions. Figure 2 depicts fluctuations in voice F0 obtained under experimental conditions in which auditory feedback was modulated at frequencies from 1 to 10 Hz (resonance curve) and under a control condition in which auditory feedback was not modulated (physiologic tremor) for a representative subject. While large amplitude peaks in the physiologic tremor spectrum obtained under the control conditions are absent, there are slight increases in amplitude at 2 Hz and at 6 to 8 Hz. The higher frequency peak (6 to 8 Hz) is within the range of F0 modulation typically associated with normal tremor (Marsden, 1984). The resonance curve is a composite curve that depicts the amplitude of energy present at each frequency in response to sinusoidal modulation of feedback at those frequencies. The average resonance curve shows greater amplitude of energy, at frequencies ranging from 1 to 7 Hz, than is shown in the curve depicting physiologic tremor. A single peak in the average resonance curve occurred at 5 Hz, indicating that the greatest amplitude of energy was present at this frequency. Amplitude extent of modulation ranged from 8 to 16 cents across the six subjects (mean=10.4, SEM=3.5).

FIG. 2.

Long-time power spectra for a representative subject. The physiologic tremor curve (solid squares) depicts tremor present in the voice signal in the absence of modulated auditory input. Observed spectral peaks at 2 Hz and at 6 to 8 Hz indicate increases in physiologic tremor. The resonance curve (open squares) reflects the composite energy present in the voice signal during modulated auditory feedback. This curve shows a spectral peak at 5 Hz indicating natural resonance of pitch-shift reflex at this frequency. The spectral peak at 1 to 2 Hz may represent a voluntary response to modulated auditory feedback.

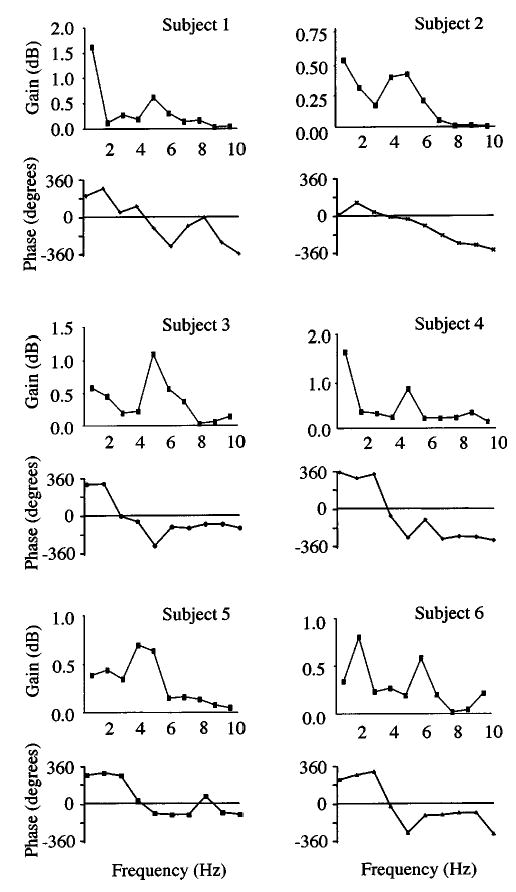

Transfer functions for gain and phase are plotted for all subjects in Fig. 3. The transfer functions of gain (upper trace) show that greatest gains, or peaks, occurred at modulation frequencies within the vibrato frequency range (4 to 7 Hz) in all subjects. Although there were occasional peaks in the gain plots at low frequencies, these most likely reflected voluntary modulations in F0. The transfer functions of phase (lower trace) show that the voice output and modulated auditory feedback signals were in-phase at 3 to 5 Hz across all subjects. The voice output signals were phase-advanced at low frequencies (2 Hz) and phase-lagged at mid to high frequencies (5 to 10 Hz) relative to the modulated auditory feedback signals for all subjects. Transfer functions of gain and phase averaged across all subjects (Fig. 4) illustrate the essential features of the gain and phase characteristics described above.

FIG. 3.

Transfer functions of gain (upper trace) and of phase (lower trace) for all subjects. The transfer functions of gain depict the amount of energy present in the voice signal relative to the energy present in the modulated auditory signal. Peak gains occurred at frequencies ranging from 4 to 7 Hz indicating that the pitch-shift reflex demonstrated greatest gain at frequencies consistent with vibrato. Low-frequency peaks observed in the transfer functions of each subject may have resulted from voluntary responses to modulated auditory feedback. The transfer functions of phase show the phase relationship between voice output and modulated auditory feedback signals. Voice output and auditory feedback signals were in-phase at frequencies between 3 and 5 Hz.

FIG. 4.

(a) Average transfer function of gain. Peak gain occurred at 5 Hz, which is consistent with peak gain in vibrato. The low-frequency peak at 1 to 2 Hz may have resulted from voluntary adjustment to pitch in response to modulated auditory feedback. (b) Average transfer function of phase. Voice output and modulated auditory feedback signals were in-phase at 4 Hz.

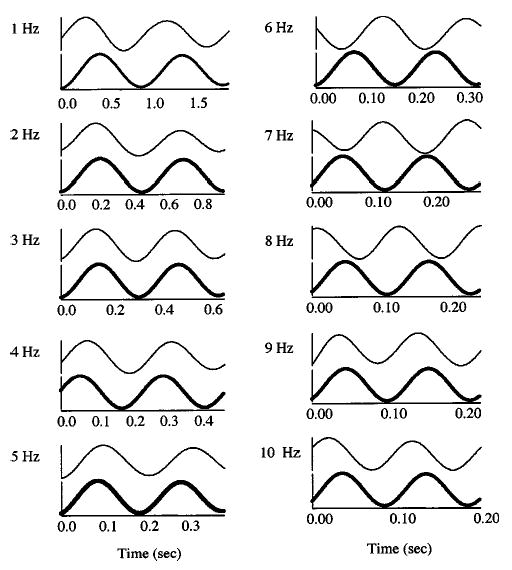

Time-aligned auditory feedback and voice output signals revealed a similar pattern. Figure 5 shows two cycles of time-aligned modulated auditory feedback (upper trace) and the corresponding voice output signal (lower trace) for one subject. The auditory feedback signal was phase-advanced at low frequencies (1–3 Hz), in-phase at mid frequencies (4 Hz), and phase-lagged at high frequencies (5–10 Hz).

FIG. 5.

Time-aligned voice output signal (upper trace) and modulated auditory feedback signal (lower trace) at each modulation frequency (1 to 10 Hz) for a representative subject. Two cycles of modulated auditory feedback are shown at each modulation frequency. The signals are most in-phase at modulation frequencies from 3 to 5 Hz. Greatest amplitude of response occurred when the voice output and auditory feedback signals were most in-phase. The large amplitude responses observed at 1 to 2 Hz may have been due to voluntary adjustments in response to modulations in auditory feedback.

IV. DISCUSSION

Our findings support the hypothesis that reflexes in the audio-vocal system can sustain vibratolike oscillations in voice F0 in response to an imposed continuous sinusoidal modulation of the auditory feedback signal. Sinusoidal modulations of auditory feedback pitch elicited a pitch-shift reflex (PSR) resulting in oscillations in voice F0 at frequencies close to twice the predicted latency of the PSR loop. Transfer functions for all subjects showed greatest gain in spectral energy of voice output between 4 and 7 Hz, with a mean peak gain at 5 Hz, indicating that the PSR elicited the greatest response to modulated auditory feedback at rates consistent with those typically observed in vocal vibrato. Furthermore, the greatest gains were obtained at modulation frequencies where the modulated auditory feedback and the voice output signals were most in-phase. Our findings suggest that the PSR has a natural frequency that falls within the frequency range associated with vibrato and is consistent with the observed natural frequency of auditory response of 6.6 Hz observed by Kawahara and Williams (1996).

We observed low frequency peaks in transfer functions for all subjects (Fig. 3). The low frequency peaks may represent a voluntary adjustment to pitch in response to modulations in the auditory signal (Sapir and McClean, 1983). This interpretation is consistent with the hypothesis posited by Kawahara and Williams (1996) that pitch can be altered voluntarily at low frequencies in response to modulated auditory feedback. Alternatively, the low frequency peaks may reflect the effects of heartbeat on F0 (Orlikoff and Baken, 1989). For these reasons, we do not consider these low frequency peaks in gain to result from the effects of PSR on voice F0 and therefore we omitted them from further interpretation.

Sinusoidal modulation of auditory feedback elicited vibratolike oscillations in F0 in the vocal output signal. However, the extent of F0 oscillations in the voice output signal, as measured by the amplitude of energy at the spectral peak of modulated voice output, was lower than the 1–1.5 semi- tone range typical of vibrato. Extent of F0 oscillations in the voice output signal following ±25 cents feedback modulation did not exceed ±8 cents in any subject. The relatively low extent of F0 modulation observed in the present study suggests that the PSR determines the rate, not the extent of F0 oscillations. This further suggests that rate, not extent, of F0 oscillations may be controlled by reflexes in the auditory pathway. Based on our results, however, we cannot rule out the possibility that the extent of modulation of F0 may have been depressed due to two factors. First, the extent of modulation of F0 in vibrato is associated with the musical (Prame, 1995) and emotional (Seidner et al., 1995) context of the piece. In the present study, the subjects were instructed to produce a steady pitch in a laboratory setting. Second, singers demonstrate more finely tuned oscillations associated with a greater spectral peak, and consequently greater extent, than nonsingers (Titze et al., 2002). Had trained singers been asked to produce vocal vibrato, the extent of F0 modulations may have been greater.

There was some variability in peak modulation frequency within the vocal vibrato range across subjects. On average, we observed greatest gain in voice output following modulation in auditory feedback at 5 Hz, with individual subjects’ gains ranging from 4 to 7 Hz. Thus, while all subjects demonstrated greater energy at frequencies within the acceptable range for vocal vibrato, intersubject variability in frequency of peak gains was observed. This intersubject variability may have been attributable to differences in latency of the PSR across subjects. If a subject’s PSR has a latency of ~100 ms, the peak in the voice modulated signal will be expected to occur at 5 Hz (the reciprocal of 200 ms). If the PSR is slower or faster than 100 ms, spectral peaks will be observed at a lower or higher frequency, respectively. Subjects may exhibit differences in latencies of the PSR due to nonuniform attendance to the pitch modulations (Burnett et al., 1998; Larson et al., 1996). Alternatively, subjects may use idiosyncratic strategies to produce the same vocal output (Sapir and Larson, 1993; Ramig and Shipp, 1987). That is, different muscle combinations and different levels of muscle activity may be used to produce vocal vibrato. As the vis-coelastic properties of muscles vary, nonuniform responses to input from the auditory pathway are expected. Additionally, subjects may be able to modify the gain in their PSR loop by altering the characteristics of underlying neuromuscular mechanisms through task-dependent latency modulation (Hain et al., 2000). Titze et al. 1994 hypothesized that the output of the central oscillators may be altered through training. At the peripheral level, singers may make adjustments to biomechanical properties of muscles (Sapir and Larson, 1993) which would alter the latency and magnitude of response of the muscles to input from the auditory reflex pathway and thereby increase or decrease the rate and magnitude of F0 modulation. Finally, subjects may have intrinsic differences in the speed of neural transmission through the pathways associated with the PSR.

The extent of intensity modulation associated with variations in F0 of the vocal output signal was not analyzed in the present study. It is possible that F0 modulations imposed on the voice signal resulted in amplitude modulation in the auditory feedback signal due to resonance-harmonics interactions (Horii, 1989; Horii and Hata, 1988). That is, as a result of changes in F0, the amplitude of the auditory feedback signal could have risen and fallen as harmonics moved closer and then further from the resonant frequencies of the vocal tract. Therefore, at present, we cannot rule out the possibility that subjects responded to changes in the intensity in addition to changes in the pitch of the auditory feedback signal.

Auditory feedback provides important information for fine-tuning voice output for singing. Deutsch and Clarkson (1959) suggested that a control loop within the auditory system maintains vibratolike oscillations in F0. The findings of the present study are consistent with this hypothesis. We demonstrated that sinusoidal modulations in auditory feedback sustained oscillations in voice F0 through consecutive compensatory reflexive responses. These oscillations occurred at approximately 5 Hz, which is the reciprocal of twice the latency of the pitch shift reflex. We propose that a negative feedback control loop within the auditory system, involving the PSR, drives F0 oscillations associated with vocal vibrato. Given that vocal tremor shares many acoustic and EMG similarities with vibrato, we speculate that reflexes in the auditory pathway may play a role in sustaining vocal tremor during voicing in some individuals. Hain et al. 2001 hypothesized that abnormal timing in the auditory pathway may result in vocal tremor. Future studies should be directed at evaluating the role of the control loops within the auditory system in triggering or sustaining vocal tremor.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant No. DC02764-01 awarded to Dr. Charles R. Larson, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

A portion of this material was presented in “Observations on the relation between auditory feedback and vocal vibrato” at the Third Biennial International Conference for Voice Physiology and Biomechanics, Denver, Colorado, September 2002.

References

- Brown WS, Rothman HB, Sapienza CM. Perceptual and acoustic study of professionally trained versus untrained voices. J Voice. 2000;14:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(00)80076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett TA, Larson CR. Early pitch-shift response is active in both steady and dynamic voice pitch control. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112:1058–1063. doi: 10.1121/1.1487844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett TA, Senner JE, Larson CR. Voice F0 responses to pitch-shifted auditory feedback: A preliminary study. J Voice. 1997;11:202–211. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(97)80079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett TA, Freedland M, Larson CR, Hain T. Voice F0 responses to manipulations in pitch feedback. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;103:3153–3161. doi: 10.1121/1.423073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson JK, Deutsch JA. Effect of threshold reduction on the vibrato. J Exp Psychol. 1966;71:206–210. doi: 10.1037/h0023093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejonckere PH. Fascinating and Intriguing Vibrato. In: Dejonckere PH, Hirano M, Sundberg J, editors. Vibrato. Singular; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch JA, Clarkson JK. Nature of the vibrato and the control loop in singing. Nature (London) 1959;183:167–168. doi: 10.1038/183167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath TM, Natke U, Kalveram KT. Effects of frequency-shifted auditory feedback on voice F0 contours in syllables. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;111:357–366. doi: 10.1121/1.1424870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hain TC, Burnett TA, Larson CR, Kiran S. Effects of delayed auditory feedback (DAF) on the pitch-shift reflex. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001;109:2146–2152. doi: 10.1121/1.1366319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hain TC, Larson CR, Burnett TA, Kiran S, Singh S. Instructing participants to make a voluntary response reveals the presence of two vocal responses to pitch-shifted stimuli. Exp Brain Res. 2000;130:133–141. doi: 10.1007/s002219900237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horii Y. Frequency modulation characteristics of sustained /a/ sung in vocal vibrato. J Speech Hear Res. 1989;32:829–836. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3204.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horii Y, Hata K. A note on phase relationships between frequency and amplitude modulation in vocal vibrato. Folia Phoniatr. 1988;40:303–311. doi: 10.1159/000265924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsaoi TY, Solomon NP, Luschei ES, Titze IR. Modulation of fundamental frequency by laryngeal muscles during vibrato. J Voice. 1994;8:224–329. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(05)80293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inbar G, Eden G. Physiological evidence for central modulation of voice tremor. Biol Cybern. 1983;47:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00340063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Munhall KG. Perceptual calibration of F0 production: evidence from feedback perturbation. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;53:1246–1251. doi: 10.1121/1.1288414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara H, Williams JC. Effects of auditory feedback on voice pitch trajectories: characteristic responses to pitch perturbations. In: Davis PJ, Fletcher NH, editors. Vocal Fold Physiology: Controlling Complexity and Chaos. Singular; San Diego: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- King JB, Horii Y. Vocal matching of frequency modulation in synthesized vowels. J Voice. 1993;7:151–159. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(05)80345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koda J, Ludlow C. An evaluation of laryngeal muscle activation in patients with vocal tremor. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:684–696. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane H, Tranel B. The Lombard sign and the role of hearing in speech. J Speech Hear Res. 1971;14:677–709. [Google Scholar]

- Larson CR, White JP, Freedland MB, Burnett TA. Interactions between voluntary modulations and pitch-shifted feedback signals: Implications for neutral control of voice pitch. In: Davis PJ, Fletcher NH, editors. Vocal Fold Physiology: Controlling Complexity and Chaos. Singular; San Diego: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen AM. Artificial pitch changing in auditory feedback as a possible method in voice training and therapy. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 1994;46:86–89. doi: 10.1159/000266297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold O. Physiological Tremor. Sci Am. 1971;224:65–71. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0371-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin CM, McAdams S. Segregation of concurrent sounds. II: Effects of spectral envelope tracing, frequency modulation coherence, and frequency modulation width. J Acoust Soc Am. 1991;89:341–351. doi: 10.1121/1.400469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden CD. Origins of Normal and Pathological Tremor. In: Findley LJ, Capildeo R, editors. 1984. Disorders in Movement: Tremor. Oxford UP; New York: [Google Scholar]

- Niimi N, Horigushci S, Kobayashi N, Yamada M. Electromyographic study of vibrato and tremolo in singing. In: Fujimura O, editor. Vocal Physiology: Voice Production, Mechanisms, and Function. Raven; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Orlikoff RF, Baken RJ. The effect of heartbeat on vocal fundamental frequency perturbation. J Speech Hear Res. 1989;32:576–582. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3203.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prame E. Measurement of the vibrato rate of ten singers. In: Dejonckere PH, Hirano M, Sundberg J, editors. Vibrato. Singular; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ramig L, Shipp T. Comparative measures of vocal tremor and vocal vibrato. J Voice. 1987;1:162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg M, Miller D, Molitor R. Aerodynamic investigation of sources of vibrato. Folia Phoniatr. 1988;40:244–260. doi: 10.1159/000265915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir S, Larson KK. Supralaryngeal muscle activity during sustained vibrato in four sopranos: Surface EMG findings. J Voice. 1993;7:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(05)80329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir S, McClean MD. Effects of frequency-modulated auditory tones on the voice fundamental frequency in humans. J Acoust Soc Am. 1983;73:1070–1073. doi: 10.1121/1.389135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seashore CE. Psychology of Music. McGraw–Hill; New York: 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Seidner S, Nawka T, Cebulla M. Dependence of the vibrato on pitch, musical intensity, and vowel in different voice classes. In: Dejonckere PH, Hirano M, Sundberg J, editors. Vibrato. Singular; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shipp T, Izdebski K. Current evidence for existence of laryngeal macrotremor and microtremor. J Forensic Sci. 1981;26:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipp T, Sundberg J, Haglund S. A model of frequency vibrato. In: van Lawrence L, editor. Transcripts of the 11th Symposium Care of the Professional Voice. Voice Foundation; New York: 1984. pp. 116–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg J. The Science of the Singing Voice. Northern Illinois U.P; Dekalb: 1987. pp. 168–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg J. Acoustic and psychoacoustic aspects of vocal vibrato. In: Dejonckere PH, Hirano M, Sundberg J, editors. Vibrato. Singular; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Titze IR. Coupling of neural and mechanical oscillators in control of pitch, vibrato, and tremor. In: Davis PJ, Fletcher NH, editors. Vocal Fold Physiology: Controlling Complexity and Chaos. Singular; San Diego: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Titze IR, Solomon NP, Luschei ES, Hirano M. Interference between normal vibrato and artificial stimulation of laryngeal muscles at near vibrato rates. J Voice. 1994;8:215–223. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(05)80292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titze IR, Story B, Smith M, Long R. A reflex resonance model of vocal vibrato. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;111:2272–2282. doi: 10.1121/1.1434945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennard W. Singing: The Mechanism and the Technique. Carl Fisher; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Winckel F. Acoustic cues in the voice for detecting laryngeal diseases and individual behavior. In: Wyke B, editor. Ventilatory and Phonatory Control Systems: An International Symposium. Oxford U. P.; London: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Larson CR, Bauer JJ. On-line processing of voice pitch feedback during production of mandarin tones; presented at the Third Biennial International Conference on Voice Physiology and Biomechanics; Denver, CO.. 2002. [Google Scholar]