Abstract

Background

The effective functional analysis of male gametophyte development requires new tools enabling the spatially and temporally controlled expression of both marker genes and modified genes of interest. In particular, promoters driving expression at earlier developmental stages including microspores are required.

Results

Transcriptomic datasets covering four progressive stages of male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis were used to select candidate genes showing early expression profiles that were male gametophyte-specific. Promoter-GUS reporter analysis of candidate genes identified three promoters (MSP1, MSP2, and MSP3) that are active in microspores and are otherwise specific to the male gametophyte and tapetum. The MSP1 and MSP2 promoters were used to successfully complement and restore the male transmission of the gametophytic two-in-one (tio) mutant that is cytokinesis-defective at first microspore division.

Conclusion

We demonstrate the effective application of MSP promoters as tools that can be used to elucidate gametophytic gene functions in microspores in a male-specific manner.

Background

The male gametophyte of flowering plants displays a highly reduced structure of two or three cells at maturity and its development provides an excellent system to study many fundamentally important biological processes such as cell polarity, cell division and cell fate determination (reviewed by [1]). An increasing collection of mutations and genes have been characterized that act gametophytically and have been shown to be important for post-meiotic cell division during pollen development in Arabidopsis. These include MOR1/GEM1 [2] and TIO [3], whose functions are essential for regular cell polarity and cytokinesis at first microspore division, termed pollen mitosis I. However, mutations in such essential genes cause gametophytic embryo sac defects and sporophytic lethality [2,3]. This prevents the analysis of homozygous mutations and hinders the functional analysis of their role(s) in specific cell types such as microspores. The native promoters of essential genes such as TIO are not useful tools to examine effects of mis-expression of gene or protein domains during pollen development since their broad activities in other sporophytic tissues can be detrimental to early vegetative development prior to gametophytic development. Moreover the use of well characterized male-gametophyte-specific promoters such as LAT52 enables targeted manipulation of gene expression that is restricted to the vegetative cell during pollen maturation after pollen mitosis I ([4]. Therefore we have faced a practical challenge to identify promoters that allow the targeted manipulation of gene expression in microspores.

A number of male-gametophyte-specific promoters that are active at different developmental stages are known. Most data are available for late pollen promoters. These include petunia chiA [5], tomato LAT52 and LAT59 [4,6], rapeseed Bp10 [7], maize Zm13 [8,9] and tobacco NTP303 [10]. In Arabidopsis these include the TUA1 [11], AtPTEN1 [12], AtSTP6 [13], AtSTP9 [14] and the late vegetative cell-specific AtVEX1 [15] promoters. Among these, the tomato LAT52 promoter with demonstrated vegetative-cell-specific expression [4,6] was shown to be highly active in number of plant species and has become widely used as a tool to drive pollen-specific expression [16-20]. More recently, promoters active in generative or sperm cells have been identified from lily [21] and Arabidopsis [15,22,23].

On the other hand, very few promoters have been identified that are active or specifically active at microspore stage. The tobacco NTM19 promoter is the only well characterized promoter that exhibits strict microspore-specific expression with no activity in mature pollen [24,25]. From rapeseed, Bp4 mRNA was described as microspore-specific [26], but the Bp4 promoter was later shown to be active only after PMI [24]. However the BnM3.4 promoter was active in tetrads and in free microspores [27]. The potato invGF promoter is initiated in late microspores and is restricted to the male gametophyte [28]. In Arabidopsis available microspore expressed promoters are also limited. The Arabidopsis BCP1 promoter is active in microspores and the tapetum [29] while the AtSTP2 promoter shows a pattern of activity similar to that of NTM19, but is initiated at tetrad stage [30].

Transcriptomic analyses based on various microarray experiments including those from isolated microspores and developing pollen now provide genome-wide expression profiles throughout plant development [31-33]. Taking advantage of these public databases, we have asked whether microarray data can be directly exploited in order to identify novel and potentially specific promoters that are first active in Arabidopsis microspores. In this study, we have selected and characterized the activity of three promoters, MSP1, MSP2, and MSP3 that were predicted to be specifically active in microspores and developing pollen. We demonstrate that the MSP1 and MSP2 promoters can drive functional protein expression in microspores in complementation experiments and the utility of MSP promoters as novel male-specific microspore expression tools in Arabidopsis.

Results

Identification of candidate genes

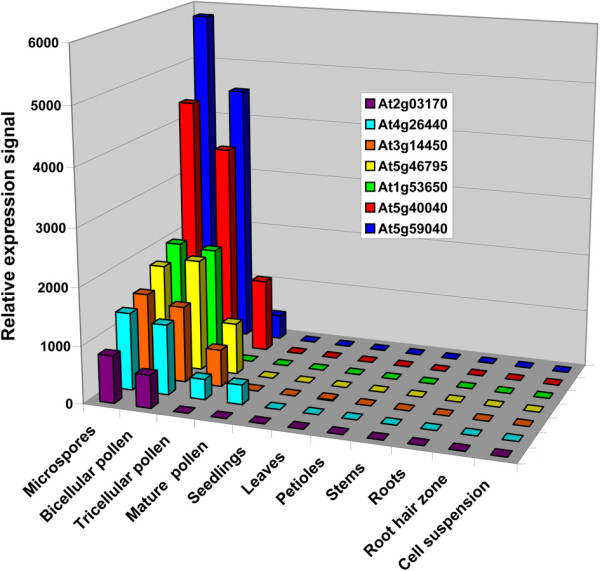

To identify regulatory sequences that direct preferential or specific expression in Arabidopsis microspores we analyzed normalized transcriptomic datasets. We compared the expression profiles of all gametophytically expressed genes with those expressed in the sporophyte. The male gametophyte microarray data set was obtained from our previous experiments involving analysis of four developmental stages; microspore, bicellular, tricellular and mature pollen [33]. Sporophytic datasets were obtained from publicly available resources (NASC). We selected for genes exhibiting strict expression patterns at early stages of male gametophyte development with no or low signals in mature pollen. Genes with expression in inflorescences, flower buds [31,34] and developing flowers [32] were retained as candidate genes, but genes with reliable signals in other sporophytic dataset(s) were excluded. Genes were further selected to retain those encoded as single copy genes and that showed a range of expression levels in microspores. This approach led to the identification of seven potential target genes (At5g40040, At5g59040, At5g46795, At4g26440, At2g03170, At3g14450 and At1g53650; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Expression profiles of candidate genes selected for promoter analyses. Expression profiles of seven genes were compared in available male gametophytic and sporophytic transcriptomic datasets. Individual transcriptomic experiments are described in Material and methods.

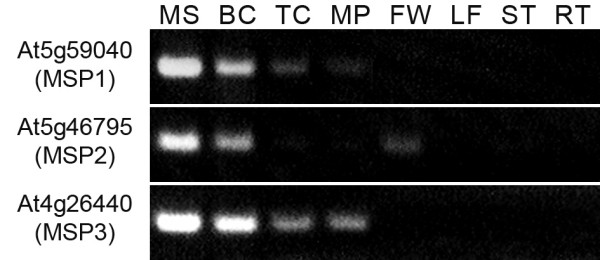

The direct comparison of gene expression levels obtained from independent microarray datasets for male gametophytic cells and for sporophytic tissues is difficult [1,35]. Therefore, the putative specificity of gene expression from microarray analyses was verified by RT-PCR analysis using RNA samples isolated from four stages of male gametophyte development, unicellular, bicellular, tricellular and mature pollen, and four sporophytic tissues and organs (flowers, leaves, stems and roots). Four genes showed expression in one or more sporophytic tissues and were eliminated from further characterization. The remaining three genes showed microspore-specific expression by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2). During selection we did not exclude genes from further analysis that also showed weak expression in open flowers since these contain mature pollen grains.

Figure 2.

Verification of microarray gene expression data by RT-PCR. The expression of three genes selected for further GUS expression assays was examined in microspores (MS); bicellular (BC), tricellular (TC) and mature pollen (MP); whole flowers (FW); leaves (LF); stems (ST) and roots (RT).

The putative microspore-specific promoter sequences of these genes, At5g59040, At5g46795, At4g26440, were termed MSP1, MSP2 and MSP3 respectively. Selected genes encoded proteins with quite distinct cellular functions. At5g59040 encodes COPT3, a putative pollen-specific member of a copper transporter family [36]. At4g26440 encodes AtWRKY34, a group I WRKY family transcription factor [37]. On the contrary, At5g46795 encodes an expressed protein of unknown function.

Histochemical analysis of promoter specificity

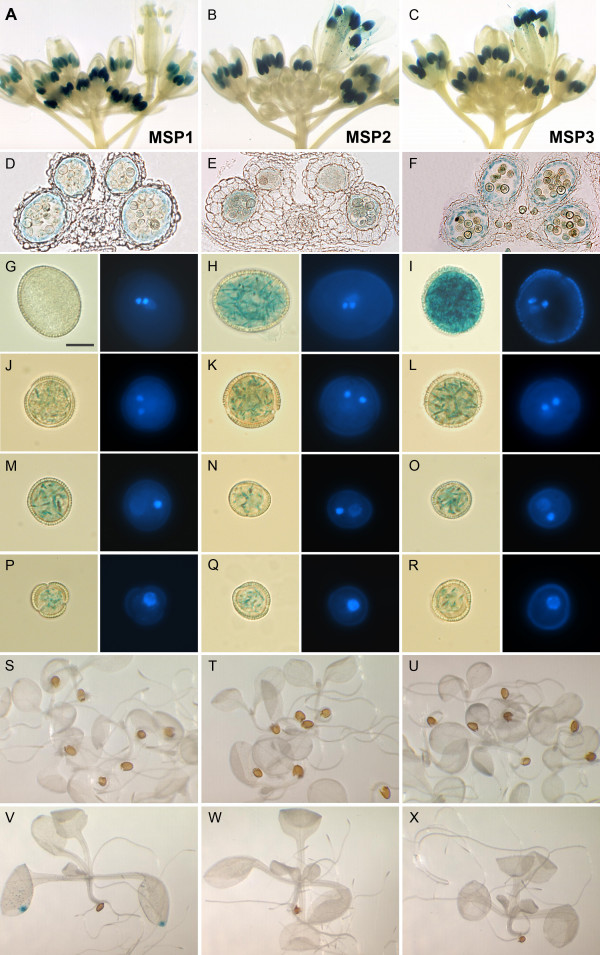

To test the activity of the selected MSP regulatory sequences in vivo, approximately 1 kb upstream genomic fragments were amplified for each of the genes and cloned into the GATEWAY-compatible destination vector, pKGWFS7 [38]. Three MSP-GFP::GUS constructs, MSP1 (At5g59040), MSP2 (At5g46795) and MSP3 (At4g26440), were introduced into wild type Arabidopsis plants and ~40 T1 transformants were analyzed histochemically for GUS activity in inflorescences, bud clusters and flowers. We found that 38/40 MSP1, 36/38 MSP2 and 18/34 MSP3 plants showed GUS expression in flower buds and/or in open flowers. GUS staining in MSP1 plants was clearly detectable in anthers of younger buds than those from MSP2 and MSP3, but gradually became weaker towards anthesis, while GUS expression from MSP2 and MSP3 remained high at later stages including in mature pollen grains.

Segregation analysis revealed that the majority of lines segregated 3:1 for kanamycin-resistant and kanamycin-sensitive plants. Plants that were hemizygous for MSP constructs showed 1:1 segregation of GUS staining and non-staining spores consistent with gametophytic expression (data not shown). We examined gametophytic expression in detail by staining isolated spores at different developmental stages and by sectioning stained flower buds. For all three promoters, GUS expression was first detectable in uninucleate microspores (Fig. 3P–R). Another common feature was that anther transverse sections clearly showed GUS staining in the tapetum (Fig 3D–F). Differences in expression profiles were noted between MSP1 and the other two promoters. While MSP1 showed earlier staining in microspores then a strong decline in mature flowers, MSP2 and MSP3 initiate expression in microspores, but GUS expression peaks later and accumulates in mature pollen.

Figure 3.

In situ GUS expression driven by three promoters, MSP1 (A, D, G, J, M, P, S and V), MSP2 (B, E, H, K, N, Q, T and W) and MSP3 (C, F, I, L, O, R, U and X). GUS staining in whole inflorescences (A, B, C); transverse sections of whole anthers (D, E, F); five-day (S, T, U) and ten-day old (V, W, X) seedlings. Light and DAPI-stained fluorescence images of mature pollen (G, H, I), immature tricellular pollen (J, K, L) bicellular pollen (M, N, O) and uninucleate microspores (P, Q, R) are shown.

We also examined GUS expression in seedlings using ~20 lines of T2 generation plants for each construct and found no expression from all three MSP promoters, apart from 5–10% of anomalous lines that showed patchy expression in leaves and roots, or weak expression in stamen vascular tissues. None of the lines examined showed GUS activity in 5 day old seedlings. However interestingly, we consistently observed GUS activity at the distal tip of cotyledons and leaves in 10 day old MSP1-GUS seedlings (Fig. 3V). In summary all 3 MSP promoters were found to be specifically or highly preferentially expressed in microspores, developing pollen and the tapetum (Fig. 3)

Complementation analysis

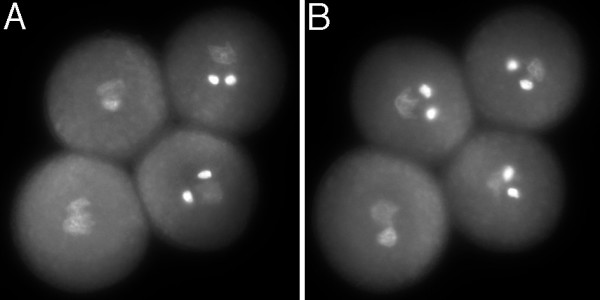

To evaluate MSP promoters as tools for the manipulation of microspore gene expression in planta, we examined whether gene expression driven by MSP1 and MSP2 could complement a gametophytic mutant phenotype caused by defects that are known to depend upon gametophytic expression in developing microspores. Mutations in the Arabidopsis TWO-IN-ONE (TIO) protein kinase result in binucleate pollen grains due to the failure of cytokinesis in microspores at pollen mitosis I. Plants that are heterozygous for the T-DNA insertion allele, tio-3, show 50 % mutant pollen that results in a 2:2 segregation of wild type and mutant pollen in tetrads (Fig. 4A). Moreover cytokinesis defects in mutant tio-3 pollen completely block genetic transmission of tio-3 through pollen [3].

Figure 4.

Mature pollen tetrad phenotype after DAPI staining. (A) Tetrad from +/tio-3;qrt1/qrt1 plant showing 2:2 segregation of wild type and tio mutant pollen. (B) Tetrad from a transformant containing MSP1-TIO in the +/tio-3;qrt1/qrt1 background, showing three pollen grains with a wild type phenotype and a single mutant tio pollen grain.

Test vectors were built in which MSP1 or MSP2 promoters drive the expression of full length TIO cDNA. pMSP1-TIO and pMSP2-TIO. Both vectors were transformed into tio-3 plants by floral dipping. Double selection for tio-3 (ppt) and pMSP-TIO (kanamycin) constructs led to the isolation of 19 nineteen transformants containing pMSP1-TIO and 10 containing pMSP2-TIO. Plants were screened for the frequency of wild type and mutant spores in mature pollen tetrads after DAPI staining. 18/19 lines from pMSP1-TIO and 4/10 from pMSP2-TIO showed an increase in the frequency of wild type pollen compared to heterozygous tio-3 plants (data not shown). This resulted in the frequent appearance of mature tetrads with three wild type spores and one mutant member, compared with heterozygous tio-3 plants that always showed a 2:2 segregation (Fig. 4).

We further tested genetic transmission of the tio-3 mutant allele in 15 complementing pMSP1-TIO lines and all of four complementing lines from pMSP2-TIO. In the F1 progenies generated from test crosses in which the pollen donor carried tio-3 and pMSP-TIO we observed approximately 30 to 50 % pptR progeny for pMSP1-TIO and 8 to 33 % for pMSP2-TIO. Table 1 shows the results for four representative lines for each construct. These results clearly demonstrate that gametophytic expression of the full-length TIO cDNA under the control of MSP1 and MSP2 promoters is sufficient to complement the tio pollen phenotype. Moreover, our results indicate that MSP1 is more effective than MSP2 in this complementation assay.

Table 1.

Complementation analysis

| % mutant pollen | KmR:KmS T2 |

pptR:pptS F1 |

% pptR F1 |

|

| pMSP1-TIO-3 | 28.7 | 48:12 | 30:61 | 32.96 |

| pMSP1-TIO-9 | 14.5 | 103:5 | 284:294 | 49.13 |

| pMSP1-TIO-10 | 11.9 | 91:10 | 193:237 | 44.88 |

| pMSP1-TIO-18 | 27.9 | 56:18 | 43:90 | 32.33 |

| pMSP2-TIO-1 | 40.3 | 323:67 | 41:145 | 22.04 |

| pMSP2-TIO-2 | 43.3 | 91:15 | 29:156 | 15.68 |

| pMSP2-TIO-5 | 29.2 | 88:3 | 29:60 | 32.58 |

| pMSP2-TIO-8 | 46.6 | 85:31 | 11:131 | 7.75 |

| +/tio-3 | 50.6 | - | 0:215 | 0 |

Four lines harbouring each construct were compared to the heterozygous parent plant, tio-3. The % of mutant pollen was scored after DAPI staining and the T2 segregation of the complementing T-DNA (MSP-TIO) was analysed on kanamycin media. The extent of male transmission (% pptR) of tio-3 was determined on ppt media in F1 progenies from test-crosses.

Discussion

We developed a strategy to identify promoters expressed specifically in Arabidopsis microspores by exploiting in silico analyses and in vivo functional analysis. We tested the specificity and timing of three candidate promoters by promoter-GUS fusion analysis. All three promoters were specifically expressed in anthers with the exception of MSP1 that also showed limited expression in the distal tips of cotyledons and true leaves. Within developing flowers their expression was restricted to microspores, developing pollen and tapetal cells. Furthermore, successful use of the MSP1 and MSP2 promoters for complementation of the tio-3 mutation demonstrated that both promoters directed functional expression in uninucleate microspores before pollen mitosis I. These promoters therefore provide new tools for the functional analysis of genes and proteins expressed during microspore development. Differences in expression profiles were observed between MSP1, that showed earlier expression and a decline in mature pollen, and MSP2 and MSP3, in which expression increased during pollen maturation. These differences in GUS expression profiles were not predicted by the MSP microarray expression profiles that were very similar. This result and the minor expression patterns observed in MSP1 seedlings highlights the need for experimental verification of specificity prior to further practical analyses.

In developing stamens, cell lineages that lead to male gametophytes and tapetal cells can both be traced to archesporial cells derived from the L2 layer of anther primordial [39]. Moreover, there is strong dependence of microspore development on tapetal cell function. In this regard the co-regulation of gene expression in both microspores and tapetum that occurs at early stages of anther development is not surprising. In tobacco, a chalcone-synthase-like gene ([40] and a chimeric Ca2+calmodulin-dependent protein kinase [41]) follow this expression pattern. The Brassica campestris Bcp1 gene is also co-expressed in tapetum and microspores [29]. However the corresponding Bgp1 upstream sequences that were active in both tapetum and microspores in B. campestris and Arabidopsis exhibited pollen-specific expression in tobacco. Therefore different cis-acting sequence elements appear to be responsible for coordinated gene expression in tapetum and microspores in Brassicaceae and Solanaceae families [29]. In Arabidopsis, the ABORTED MICROSPOROGENESIS (AMS) gene encodes a MYC-class transcription factor from the basic helix-loop-helix gene family. AMS is coordinately expressed in tapetum and microspores [42]. Interestingly, the MSP3 gene encodes a member of the WRKY transcription factor family that could also have a role in coordinated gene expression in tapetum and microspores.

Conclusion

Taken together, we have characterized three Arabidopsis microspore-expressed promoters MSP1, MSP2 and MSP3 with early expression profiles specific to the male gametophyte and tapetum. The MSP1 and MSP2 promoters were used successfully to complement cytokinesis functions required to complete microspore development. These tools can be applied to manipulate gene expression in microspores and tapetum without detrimental effects that may arise from undesirable gene expression in other sporophytic tissues.

Methods

Plant material and spore isolation

Arabidopsis plants were grown in controlled-environment cabinets at 21°C under illumination of 150 mmol m-2 s-1 with a 16-h photoperiod. For spore isolation, Arabidopsis ecotype Landsberg erecta (Ler) plants were used. Isolation of spores and pollen was described [33]. Information on the purity of isolated fractions determined by light microscopy and 4,6-diamino-phenylindole staining and vital staining of isolated spore populations assessed by fluorescein-3,6-diacetate treatment were also described in [33]. Roots were grown from plants in liquid cultures as previously described [33]. Wild-type and transgenic seeds were sterilized according to published procedures [43,44]. Plants were transformed by floral dipping [45].

DNA Chip Hybridization and data normalisation and selection of potential target genes

RNA isolation and hybridization of Affymetrix ATH1 genome arrays was described in [33]. Twelve mixed and seventy-five sporophytic datasets used for comparison with the pollen transcriptome were obtained from the NASCArray database [46] through AffyWatch service [31]. Sporophytic datasets represented seven vegetative tissues (seedlings, leaves, petioles, stems, roots, root hair zone and suspension cell cultures; [33]. Mixed datasets originated from three experiments covering whole inflorescences and flower buds [31,34] and whole flower development [32].

All gametophytic and sporophytic datasets were normalized using DNA-Chip Analyzer 1.3 (dChip) [47] as described previously [33]. All raw and dChip-normalized transcriptomic datasets can be accessed and downloaded through the Arabidopsis Gene Family Profiler (aGFP) database [48].

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from 50 mg of leaves, stems, roots, inflorescences and isolated spores at each developmental stage was extracted using the RNeasy plant kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The yield and RNA purity were determined spectrophotometrically. Pollen, stem, leaf, and inflorescence samples were isolated from plants grown as described. Pollen RNA used for RT-PCR analyses was obtained from plants that were grown independently from those used to isolate RNA for microarray analysis. Samples of 1 μg total RNA were reverse transcribed in a 20-μL reaction using the ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions with the exception that the oligo(dT)15 primer was replaced with a custom-synthesized 3'-RACE primer (Tab. 2). The use of intron-spanning primer sets or nested reverse primers in cases where primers spanned no intron ensured that only cDNA was amplified. For PCR amplification, 1 μL of 50× diluted RT mix was used. The PCR reaction was carried out in 25 μL with 0.5 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Latvia), 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 20 pmol of each primer. The PCR program was as follows: 2 min at 95°C, 33 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 15 s at the optimal annealing temperature (63°C to 67°C), and 30 s at 72°C, followed by 10 min at 72°C. As a reverse primer, NESTED primer (Tab. 2) overlapping the 3'-RACE primer was used to eliminate genomic DNA amplification. The gene-specific forward primers were designed using Primer3 software [49] (Tab. 2).:

Table 2.

PCR primers used

| Primer | Primer sequence |

| cDNA construction | |

| 3'-RACE | 5'-AAGCAGTGGTAACAACGCAGAGTAC(T)30VN-3' |

| RT-PCR reverse primer | |

| NESTED | 5'-AAGCAGTGGTAACAACGCAGAGT-3' |

| RT-PCR forward primers | |

| At5g40040 | 5'-CTTATCGCTGTTGGACGAGAGAAGA-3' |

| At5g59040 | 5'-TCTGTCTCGCCGTCATTTTTGTTAT-3' |

| At5g46795 | 5'-GGCTTTGGAGACCAGACTTTTTCAG-3' |

| At4g26440 | 5'-TGGAGAGGTAGAAGAGTCCGAATCA-3' |

| At2g03170 | 5'-AGAAACACGTCGTTGACGAAGAAAG-3' |

| At3g14450 | 5'-GGCCAAGGAGTTTTTCCCTTCTTA-3' |

| At1g53650 | 5'-CTCGATCATTGAGCTCAGAAGCTGT-3'. |

| Construction of promoter::GUS reporters | |

| MSP1-F | 5'-AAAAAGCAGGCTTGTCAGTTAGCATGAAAAATTGTATGTTAG-3' |

| MSP1-R | 5'-AGAAAGCTGGGTTTGTTGTGTATACTTGTGTGTGTGTATTTA-3' |

| MSP2-F | 5'-AAAAAGCAGGCTATGTCCTACGATCAGAAGGAGGAG-3' |

| MSP2-R | 5'-AGAAAGCTGGGTAACATGTGATATTATTTTTTTGGTTTATATAGTGG-3' |

| MSP3-F | 5'-AAAAAGCAGGCTTTGTGATATAATAGGTATATATGGTAGAAC-3' |

| MSP3-R | 5'-AGAAAGCTGGGTTGCAAACCCAAGTTTCAGCTTTAAC-3' |

Primers used for cDNA synthesis, RT-PCR analyses and construction of promoter::GUS reporters. Where appropriate, appended adapters complementary to AttB1 and AttB2 primers are underlined.

Construction of promoter::GUS reporters

To examine the precise gene expression, each tested gene promoter region was fused with GUS to generate the MSP::GUS reporter using GATEWAY cloning system according to manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Promoter fragments were amplified by two-step PCR from Col-0 genomic DNA isolated from 3-week-old seedlings using the KOD HiFi DNA Polymerase (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). For the first step, specific primers with appended adapters complementary to AttB1 and AttB2 sequences were used to generate 1000-bp promoter regions of tested genes (Tab. 2). Purified PCR products were cloned via pDONR201 donor vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) into pKGWFS7 destination vector (VIB, Gent, Belgium; [38] to generate recombinant destination clones pMSP1, pMSP2 and pMSP3. All the recombinant plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 [50]. These strains were used to transform Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia using the floral dip method [45]. Transgenic progenies were selected either on one-half strength Murashige and Skoog standard medium, supplemented with 50 mg/l kanamycin on 1-week-old seedlings.

Histochemical staining of GUS activity

Histochemical assays for GUS activity in T2 generation of Arabidopsis transgenic plants were performed according to the protocol described previously [44,51]. Seedlings and inflorescences incubated for 48 h at 37°C in GUS buffer (100 mM Na-phosphate, pH 7.2; 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0; 0.1% Triton X-100; 2 mM K3Fe [CN]6) supplemented with 1 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl b-D-glucuronide (X-gluc). GUS stained floral buds were fixed in 70% FAA (Formaldehyde/Acetic acid/Ethanol/water, 5/5/63/27, v/v/v/v) for at least 24 h. After washing with 70% ethanol, samples were dehydrated gradually in the ethanol-butanol series and infiltrated with paraffin. 10 μm thin cross sections were prepared with a microtome (Finesse ME, Shandon). GUS staining patterns were recorded using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop software (version CS2; Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Complementation analysis

The full-length TIO cDNA clone, pKS-TIONC19, was modified to insert the ~1 kb MSP1 or MSP2 promoter fragments upstream of the TIO coding sequence using AscI and NotI. MSP promoter-TIO cDNA fusion fragments were subcloned into the binary vector pER10 [52] using AscI and PacI to produce pMSP1-TIO and pMSP2-TIO. Before transformation into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, constructs were verified by restriction enzyme digestion and sequencing. Individual phosphinothricin (ppt) resistant heterozygous tio-3 mutants were transformed by floral dipping [45]. Transformants containing both tio-3 and MSP promoter-TIO T-DNA constructs were selected on 15 cm MS agar plates supplemented with 10 mg/l ppt, 50 mg/l kanamycin, and 200 mg/l cefotaxime. Complementation was analyzed by scoring tio-3 pollen phenotype after 4'-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining and also by scoring the genetic transmission of tio-3 allele through male after test crosses to Col-0 or ms1-1 as described by [2,53].

Authors' contributions

DH and DT analysed microarray data and selected candidate genes. SAO constructed reporters and carried out the molecular genetic studies. DH and RB verified the gene expression profiles. SAO and JAJ performed complementation analyses. DH, SAO and DT drafted the manuscript. DR, MD, BS and DT carried out the histochemical analysis and imaging. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

DH, DR and RB gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (grant 522/06/0896) and from the Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic (grant LC06004). DT & SAO acknowledge grant support from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Contributor Information

David Honys, Email: honys@ueb.cas.cz.

Sung-Aeong Oh, Email: sao5@leicester.ac.uk.

David Reňák, Email: renak@ueb.cas.cz.

Maarten Donders, Email: M.Donders@student.science.ru.nl.

Blanka Šolcová, Email: solcova@ueb.cas.cz.

James Andrew Johnson, Email: jaj5@leicester.ac.uk.

Rita Boudová, Email: boudova@ueb.cas.cz.

David Twell, Email: twe@leicester.ac.uk.

References

- Twell D, Oh AE, Honys D. Pollen development, a genetic and transcriptomic view. In: Malhó R, editor. Plant Cell Monographs (3); The Pollen Tube. Vol. 3. Berlin, Heidelberg , Springer-Verlag; 2006. pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Twell D, Park SK, Hawkins TJ, Schubert D, Schmidt R, Smertenko A, Hussey PJ. MOR1/GEM1 has an essential role in the plant-specific cytokinetic phragmoplast. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:711–714. doi: 10.1038/ncb844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SA, Johnson A, Smertenko A, Rahman D, Park SK, Hussey PJ, Twell D. A Divergent Cellular Role for the FUSED Kinase Family in the Plant-Specific Cytokinetic Phragmoplast. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2107–2111. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twell D, Yamaguchi J, McCormick S. Pollen-specific gene expression in transgenic plants: coordinate regulation of two different tomato gene promoters during microsporogenesis. Development. 1990;109:705–713. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tunen AJ, Mur LA, Brouns GS, Rienstra JD, Koes RE, Mol JN. Pollen- and anther-specific chi promoters from petunia: tandem promoter regulation of the chiA gene. Plant Cell. 1990;2:393–401. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.5.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twell D, Yamaguchi J, Wing RA, Ushiba J, McCormick S. Promoter analysis of genes that are coordinately expressed during pollen development reveals pollen-specific enhancer sequences and shared regulatory elements. Genes Dev. 1991;5:496–507. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albani D, Sardana R, Robert LS, Altosaar I, Arnison PG, Fabijanski SF. A Brassica napus gene family which shows sequence similarity to ascorbate oxidase is expressed in developing pollen. Molecular characterization and analysis of promoter activity in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant J. 1992;2:331–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DA, Roy M, Rueda J, Sindhu RK, Sanford J, Mascarenhas JP. Dissection of a pollen-specific promoter from maize by transient transformation assays. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;18:211–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00034950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DA, Schwarz YH, Mascarenhas JP. A monocot pollen-specific promoter contains separable pollen-specific and quantitative elements. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:663–669. doi: 10.1023/A:1006083725102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weterings K, Schrauwen J, Wullems G, Twell D. Functional dissection of the promoter of the pollen-specific gene NTP303 reveals a novel pollen-specific, and conserved cis-regulatory element. Plant J. 1995;8:55–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08010055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JL, Ploense SE, Snustad DP, Silflow CD. Preferential expression of an alpha-tubulin gene of Arabidopsis in pollen. Plant Cell. 1992;4:557–571. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.5.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Ting JT, Sokolov LN, Johnson SA, Luan S. A tumor suppressor homolog, AtPTEN1, is essential for pollen development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2495–2507. doi: 10.1105/tpc.005702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz-Starke J, Buttner M, Sauer N. AtSTP6, a new pollen-specific H+-monosaccharide symporter from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:70–77. doi: 10.1104/pp.012666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidereit A, Scholz-Starke J, Buttner M. Functional characterization and expression analyses of the glucose-specific AtSTP9 monosaccharide transporter in pollen of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:182–190. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel ML, Holmes-Davis R, McCormick S. Green sperm. Identification of male gamete promoters in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2124–2133. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate N, Spurr C, Foster GD, Twell D. Maturation-specific translational enhancement mediated by the 5'-UTR of a late pollen transcript. Plant J. 1996;10:613–623. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10040613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate N, Twell D. Functional architecture of a late pollen promoter: pollen-specific transcription is developmentally regulated by multiple stage-specific and co-dependent activator elements. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:859–869. doi: 10.1023/A:1006095023050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, McCormick S. sidecar pollen, an Arabidopsis thaliana male gametophytic mutant with aberrant cell divisions during pollen development. Development. 1996;122:3243–3253. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eady C, Lindsey K, Twell D. The Significance of Microspore Division and Division Symmetry for Vegetative Cell-Specific Transcription and Generative Cell Differentiation. Plant Cell. 1995;7:65–74. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SK, Howden R, Twell D. The Arabidopsis thaliana gametophytic mutation gemini pollen1 disrupts microspore polarity, division asymmetry and pollen cell fate. Development. 1998;125:3789–3799. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.19.3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Swoboda I, Bhalla PL, Singh MB. Male gametic cell-specific gene expression in flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2554–2558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Bhalla PL, Singh MB. Transcriptional activity of male gamete-specific histone gcH3 promoter in sperm cells of Lilium longiflorum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:797–802. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotman N, Durbarry A, Wardle A, Yang WC, Chaboud A, Faure JE, Berger F, Twell D. A novel class of MYB factors controls sperm-cell formation in plants. Curr Biol. 2005;15:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custers JB, Oldenhof MT, Schrauwen JA, Cordewener JH, Wullems GJ, van Lookeren Campagne MM. Analysis of microspore-specific promoters in transgenic tobacco. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35:689–699. doi: 10.1023/A:1005846527674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenhof MT, de Groot PF, Visser JH, Schrauwen JA, Wullems GJ. Isolation and characterization of a microspore-specific gene from tobacco. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:213–225. doi: 10.1007/BF00021785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albani D, Robert LS, Donaldson PA, Altosaar I, Arnison PG, Fabijanski SF. Characterization of a pollen-specific gene family from Brassica napus which is activated during early microspore development. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:605–622. doi: 10.1007/BF00017835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourgoux-Nicol A, Drouaud J, Haouazine N, Pelletier G, Guerche P. Isolation of rapeseed genes expressed early and specifically during development of the male gametophyte. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;40:857–872. doi: 10.1023/A:1006282507095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison AL, Hedley PE, Meyer RC, Aziz N, Davidson D, Machray GC. Expression of tandem invertase genes associated with sexual and vegetative growth cycles in potato. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;41:741–751. doi: 10.1023/A:1006389013179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Davies SP, Kwan BY, O'Brien AP, Singh M, Knox RB. Haploid and diploid expression of a Brassica campestris anther-specific gene promoter in Arabidopsis and tobacco. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:58–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00281601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truernit E, Stadler R, Baier K, Sauer N. A male gametophyte-specific monosaccharide transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1999;17:191–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigon DJ, James N, Okyere J, Higgins J, Jotham J, May S. NASCArrays: a repository for microarray data generated by NASC's transcriptomics service. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D575–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig L, Gruissem W, Grossniklaus U, Kohler C. Transcriptional programs of early reproductive stages in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1765–1775. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.043182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honys D, Twell D. Transcriptome analysis of haploid male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R85. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Hennig L, Gruissem W. GENEVESTIGATOR. Arabidopsis microarray database and analysis toolbox. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2621–2632. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honys D, Renák D, Twell D. Male gametophyte development and function. In: Silva JT, editor. Floriculture, ornamental and plant biotechnology: advances and topical issues. Vol. 1. London , Global Science Books; 2006. pp. 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bock KW, Honys D, Ward JM, Padmanaban S, Nawrocki EP, Hirschi KD, Twell D, Sze H. Integrating membrane transport with male gametophyte development and function through transcriptomics. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:1151–1168. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.074708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, De Meyer B, Hilson P. Modular cloning in plant cells. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg RB, Beals TP, Sanders PM. Anther development: Basic Principles and Practical Applications. The Plant Cell. 1993;5:1217–1229. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanassov I, Russinova E, Antonov L, Atanassov A. Expression of an anther-specific chalcone synthase-like gene is correlated with uninucleate microspore development in Nicotiana sylvestris. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:1169–1178. doi: 10.1023/A:1006074508779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poovaiah BW, Xia M, Liu Z, Wang W, Yang T, Sathyanarayanan PV, Franceschi VR. Developmental regulation of the gene for chimeric calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in anthers. Planta. 1999;209:161–171. doi: 10.1007/s004250050618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen AM, Krober S, Unte US, Huijser P, Dekker K, Saedler H. The Arabidopsis ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS) gene encodes a MYC class transcription factor. Plant J. 2003;33:413–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes DC, Zayed AM, Ascenzi R, McCaskill AJ, Hoffman NE, Davis KR, Gorlach J. Growth stage-based phenotypic analysis of Arabidopsis: a model for high throughput functional genomics in plants. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1499–1510. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng NH, Pittman JK, Barkla BJ, Shigaki T, Hirschi KD. The Arabidopsis cax1 mutant exhibits impaired ion homeostasis, development, and hormonal responses and reveals interplay among vacuolar transporters. Plant Cell. 2003;15:347–364. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASCArray Database http://www.arabidopsis.info

- DNA-Chip Analyzer 1.3 http://www.dchip.org

- ArabidopsisGFP Database http://aGFP.ueb.cas.cz

- Primer 3 http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer/primer3_www.cgi

- Sambrook J, Fritch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning - a laboratory manual. Second edition. Cold Spring Harbour Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde D, Basset M, Lepetit M, Conejero G, Gaymard F, Astruc S, Grignon C. Tissue-specific expression of Arabidopsis AKT1 gene is consistent with a role in K+ nutrition. Plant J. 1996;9:195–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.09020195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo HS, Fei JF, Xie Q, Chua NH. A chemical-regulated inducible RNAi system in plants. Plant J. 2003;34:383–392. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalanne E, Michaelidis C, Moore JM, Gagliano W, Johnson A, Patel R, Howden R, Vielle-Calzada JP, Grossniklaus U, Twell D. Analysis of transposon insertion mutants highlights the diversity of mechanisms underlying male progamic development in Arabidopsis. Genetics. 2004;167:1975–1986. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]