Abstract

Tissue and organ replacement have quickly outpaced available supply. Tissue bioengineering holds the promise for additional tissue availability. Various scaffolds are currently used, whereas polyglycolic acid (PGA), which is currently used in absorbable sutures and orthopedic pins, provides an excellent support for tissue development. Unfortunately, PGA can induce a local inflammatory response following implantation, so we investigated the molecular mechanism of inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Degraded PGA induced an acute peritonitis, characterized by neutrophil (PMN) infiltration following intraperitoneal injection in mice. Similar observations were observed using the metabolite of PGA, glycolide. Dissolved PGA or glycolide, but not native PGA, activated the classical complement pathway in human sera, as determined by classical complement pathway hemolytic assays, C3a and C5a production, C3 and immunoglobulin deposition. To investigate whether these in vitro observations translated to in vivo findings, we used genetically engineered mice. Intraperitoneal administration of glycolide or dissolved PGA in mice deficient in C1q, factor D, C1q and factor D or C2 and factor B demonstrated significantly reduced PMN infiltration compared to congenic controls (WT). Mice deficient in C6 also demonstrated acute peritonitis. However, treatment of WT or C6 deficient mice with a monoclonal antibody against C5 prevented the inflammatory response. These data suggest that the hydrolysis of PGA to glycolide activates the classical complement pathway. Further, complement is amplified via the alternative pathway and inflammation is induced by C5a generation. Inhibition of C5a may provide a potential therapeutic approach to limit the inflammation associated with PGA derived materials following implantation.

Keywords: tissue bioengineering, C5a, peritonitis, neutrophils

Introduction

Organ or tissue transplantation has quickly outpaced the supply of suitable tissues available for the correction/replacement of organs lost to disease, trauma or birth defects. In addition to the scarcity of histocompatible tissue/organs, replacement of organs with either mechanical devices (e.g., valves and joints) or allografts are fraught with complications including: coagulation abnormalities, severe complications from immunosuppressive drugs and failure to grow with the recipient (i.e., mechanical devices) (1). While xenotransplants may represent a potential source for organs/tissues, this approach is complicated by significant immunological barriers (2). Thus, a suitable source of autologous tissue/organs is highly desirable.

Tissue bioengineering has the potential to produce tissues/organs. While this biotechnological field is still less than 20 years old, significant progress has been made in the development of suitable carrier materials or scaffolding, techniques for isolation of cell populations and on growth characterization of bioactive matrices. Suitably shaped tissues have been made in vitro or in vivo in immunocompromised animals, but translation to immunocompetent species is problematic (3–5). An acute inflammatory response is observed following implantation in response to the scaffolding (e.g., polyglycolic acid, PGA) and/or its degradation products (6,7). The inflammatory response is more pronounced in immunocompetent animals and the resulting production of inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-1α) degrades or impedes the production of matrix and the function of the implanted tissue (4,8).

The innate immune system is the body’s primordial host defense system. Part of the innate immune system is the complement system, a cascade of more than 30 different proteins which can be activated by three different pathways (e.g., classical, alternative and lectin). The primary inflammatory effector molecules of complement activation are the terminal complement components, C5a and C5b-9. Activation of C5 leads to generation of C5a and C5b-9 and they have been shown to be responsible for the inflammation and tissue injury in a variety of pre-clinical models and clinical studies (9–13). In regards to tissue bioengineering, biogradeable materials have been shown to interact with complement (14,15). However the specific interactions of scaffolding material and complement have not been investigated.

A localized inflammatory reaction is often observed following placement of PGA-based sutures or orthopedic pins. In these cases, the magnitude of the inflammatory response is negligible and does not lead to significant loss of benefit to the wound or a repair. However, in the case of tissue engineering, an inflammatory response to already weakened and stressed cells may result in significant cellular death and the failure of the implant. Further, the use of tissue-engineered approaches for replacing tissue lost through injury will almost certainly be placed in a donor site that may already be inflamed prior to introduction of scaffold material. Thus, depending on the tissue and nature of the donor site, local levels of inflammatory mediators may already be high, which may be exacerbated by scaffold materials such as PGA. Recent reports demonstrate that the inflammatory response to tissue engineered implants is acute, proportional to scaffolding degradation time and IL-1α staining on the implants is concentrated to the site of local scaffolding degradation, suggesting that the degrading material is responsible for the inflammatory response (16). PGA degrades via hydrolysis to glycolic acid, then dimerizes to glycolide, incorporates into the TCA cycle and is then excreted by the kidney (17–19). Thus, if the hydrolysis of PGA results in the inflammatory component of recently implanted tissues, therapeutic intervention to limit the inflammation until the glycolide is metabolized may offer protection to the newly implanted tissue and lead to better tissue development and improved graft survival. Because the observed inflammatory response is attenuated in nude mice, but acute and localized to the site of degradation of the scaffolding material in non-immunocompromised animals, we investigated the potential role of the innate immune system (i.e., complement activation) in response to the degradation of PGA in the present study.

Material/Methods

Hemolytic Assays

Sterilized PGA (Albany, International, Mansfield, MA) was degraded (H-PGA; 10 mg) for 3–4 days at 4° C in one milliliter of sterile Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline containing magnesium and calcium (DPBS) (Sigma, St. Louis), pelleted by centrifugation, the supernatant discarded and the pellet suspended in 1 ml of human serum. Non-homogenized/degraded PGA (10 mg) was suspended in 1 ml of human serum served as a control. Glycolide (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA) was dissolved in human serum at concentrations of 1 or 10 mg/ml. All samples were incubated for 30 minutes at 37° C on a rocker. Classical complement hemolytic assays were done as previously described using sensitized chicken RBCs (9)

C3 and C5 Activation in Human Sera

C3a and C5a ELISA

Sterile PGA (10 mg) was dissolve in one milliliter of gelatin veronal buffer (GVB) for 3 days at 4° C. The PGA pellet (H-PGA) was retrieved by centrifugation, and the supernatant discarded. H-PGA or native PGA (10 mg) was incubated in 5% human serum (in GVB) for 30 minutes on a rocker at 37° C, centrifuged (pellets saved for C3 deposition assay, see below) and the supernatant assayed for C3a/C3a des Arg (OptEIA Human C3a ELISA; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).

Additionally, we measured C5a anaphylatoxin biosynthesis in human sera (100%) incubated with functionally inhibitory monoclonal antibodies (50 μg/ml) to human MBL [clone 3F8 (20)], factor D [clone 166-32 (21)] or C2 [clone 175-62 (22)] to identify the complement pathways involved. The antibodies are of the IgG1 isotype and the concentrations used are in molar excess to the amount of complement components present in 100% human sera and needed to functionally inhibit their respective component (20–22). H-PGA was incubated with each of these antibody-inhibited sera for 30 min at 37° C, centrifuged and the supernatant assayed for C5a/C5a des Arg (OptEIA Human C5a ELISA; BD Biosciences).

C3 Deposition

Pellets from the C3a ELISA study above were washed in PBS thrice and then incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-human C3 pAb (1:2000; Cappel, West Chester, PA). The pellets were washed thrice in PBS, incubated with ABTS (45 ml MilliQ water, 5 ml citrate buffer, 28 mg ABTS, 50 μl 30% H2O2), centrifuged again and the supernatant read at 405 nm as previously described (23).

Immunoglobulin Deposition

Sterilized PGA (0.5 mg) was added to 0.5 ml of GVB and incubated overnight at 4° C. The pellet was retrieved by centrifugation and 0.5 ml of human sera was added to the H-PGA or 0.5 mg of non-hydrolyzed sterile PGA. The two samples were incubated at 37° C for 30 min, centrifuged, and the pellet was washed 3x with PBS. Each sample was then stained with 0.5 ml of 1:5000 peroxidase conjugated goat anti-human IgG + IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBS at RT for 1 hr. The pellets were collected again and washed 4x with PBS+0.5% Tween. The samples were developed with 0.5 ml ABTS solution and the supernatants read at 405 nm.

Peritonitis Model

All animal studies have been reviewed and approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals. Six-week-old mice C57/BL6 wild type (WT), C1qa −/− (KO)(24), factor D KO(21), C2/factor B KO(25), C1q/factor D KO, C6 deficient mice(12) were anesthetized with isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of PGA (10 mg/ml) dissolved in sterile saline for 3 days at 4° C. BB5.1 (Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Cheshire, CT), a functionally inhibitory mouse anti-mouse C5 mAb, or an isotype control mAb was given one hour before PGA injection by intraperitoneal injection at 40 mg/kg (26). Mice were euthanized by isoflurane overdose three hours after PGA injection. The peritoneal cavity was washed with 5 ml PBS (Sigma). Leukocytes were stained with 0.2% Trypan Blue, (Sigma) and counted using a hemocytometer. Slides were prepared by spinning a 1:1 solution of lavage fluid and 15% BSA (Sigma) at 2200 RPM for 4 min in a cytofuge. Slides were stained with Wright Giemsa stain (Sigma), fixed in 50 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and rinsed in distilled water. A differential white blood cell count was performed. Any lavage fluids containing red blood cells were not used. Mice in the glycolide studies were injected with 5 mg glycolide dissolved in 1 ml sterile saline. Control animals were injected with 1 ml sterile saline. We did not observe any differences between male and female mice in these studies.

Neutrophil responsiveness

We have previously demonstrated that neutrophils (PMN) from C6 deficient or factor D KO mice do not display decreased chemoattractant behavior (12,21). In order to verify that the other KO mice used in this study also display normal chemoattractant behavior, we evaluated a complement-independent chemoattractant, leukotriene (LT) B4. KO mice and their congenic controls were given LTB4 (1 μg in PBS) intraperitoneally and after one hour the leukocytes were removed, stained and counted from the peritoneal cavity as described above.

Statistics

All values are presented as mean ± sem of n independent experiments. All data were subjected to one-way ANOVA followed by posthoc analysis using SigmaStat software (SPSS Science, Chicago). Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

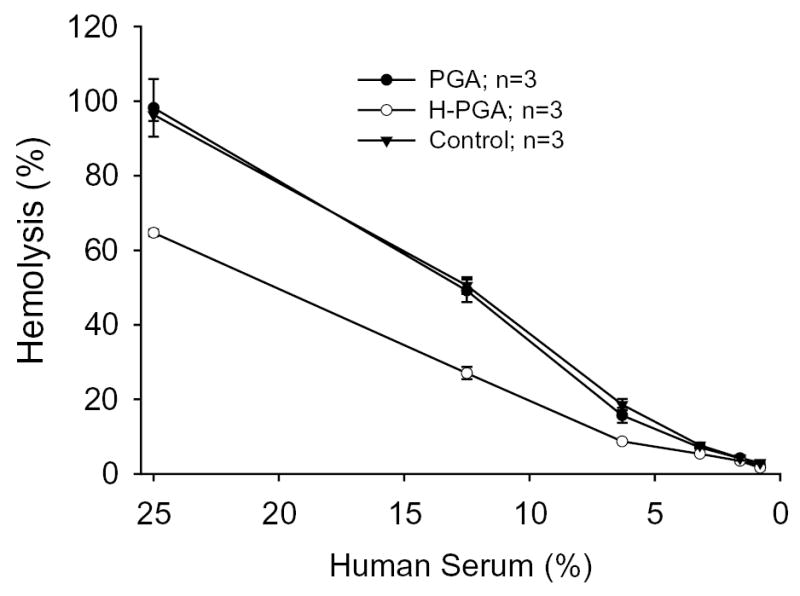

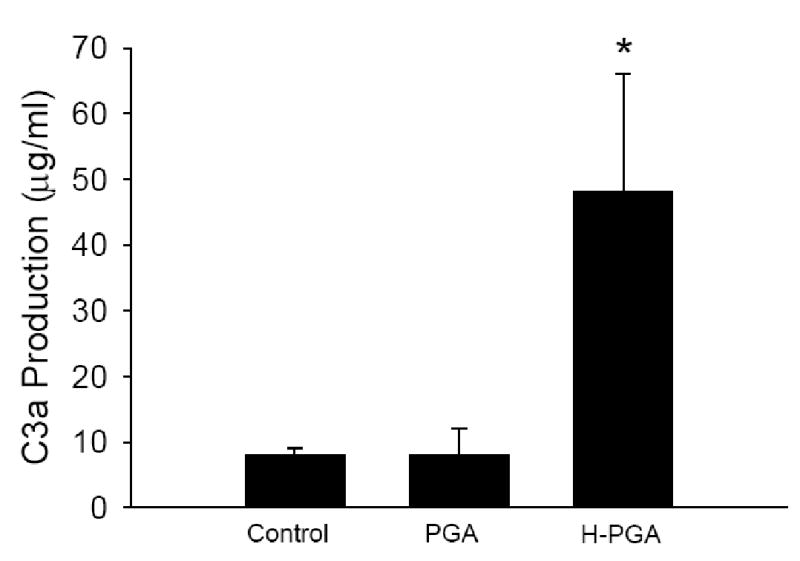

We used a classical complement hemolytic assay to determine if PGA or degraded PGA (H-PGA) incubated in human sera consumed or activated complement. As shown in Figure 1, PGA did not affect the ability of human sera to lyse RBCs. In contrast, human sera incubated with H-PGA decreased the hemolytic capacity by approximately 40%, suggesting complement consumption/activation prior to the CH50 assay. Additionally, measurement of C3a/C3a des Arg in human sera exposed to PGA or H-PGA demonstrated that C3a was only produced in the presence of H-PGA (Figure 2a). Furthermore, deposition of C3 onto H-PGA was significantly increased (~30%) compared to native PGA (data not shown). These data demonstrate that H-PGA, but not native PGA, activates complement.

Figure 1. Polyglycolic acid (PGA) and Degraded (H)-PGA Actions on Hemolytic Activity.

A hemolytic assay examining PGA degradation and complement activation was performed using sensitized chicken RBCs. Normal human sera were treated with nothing (Control), PGA or H-PGA (10 mg/ml). The “activated” sera were then used in a classic CH50 assay. Degradation of PGA lead to reduced ability of human sera to lyse RBC compared to PGA or control, demonstrating complement activation prior to incorporation into this assay. Each experiment was done in triplicate three times (n=3). Symbols and brackets represent means±SEM.

Figure 2. Anaphylatoxin Production by Degraded PGA (H-PGA).

Panel A demonstrates C3a production in human sera incubated with PGA, H-PGA or untreated human sera (Control). PGA degradation significantly increased C3a/C3a des Arg production. *, P<0.05 compared to Control or PGA. Bars and brackets represent means±SEM for 6 independent experiments.

Panel B demonstrates C5a production by degraded PGA (H-PGA) compared to unstimulated sera (control), or sera incubated with monoclonal inhibitory antibodies to factor D, MBL or C2. Clone names and dosages are listed in the Methods section. H-PGA significantly increased C5a production compared to Control. Inhibition of factor D or C2, but not MBL, significantly inhibited C5a production. *, P<0.05 compared to Control. Bars and brackets represent means±SEM for 8 independent experiments.

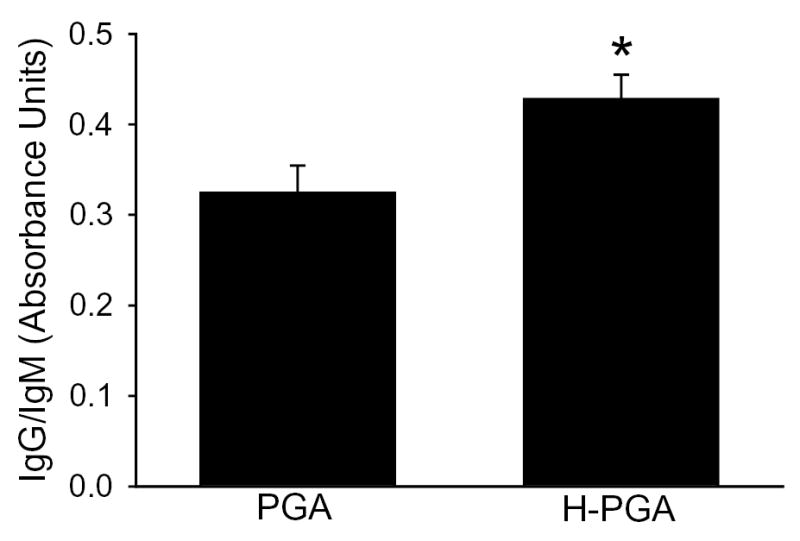

Similarly, we looked at C5a production in human sera incubated with H-PGA in the presence/absence of specific complement pathway inhibitory mAbs (Figure 2b). As shown in Figure 2b, we observed a significant increase in C5a biosynthesis in the presence of H-PGA compared to control unstimulated sera. Inhibition of either factor D or C2 inhibited C5a production suggesting activation of the classical or lectin pathway and amplification via the alternative pathway. Inhibition of the MBL complement pathway with a mAb to human MBL did not significantly attenuate C5a production. These data suggest that the classical and alternative pathways interact to produce C5a.

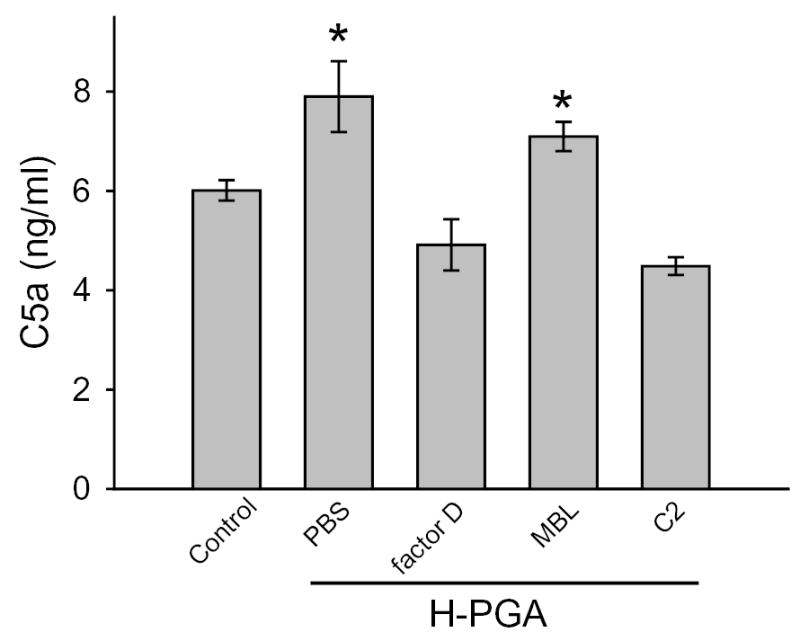

Immunoglobulin binding is central to activation of the classical complement pathway. As shown in Figure 3, we observed significant increased binding of human IgG and IgM to H-PGA compared to PGA. These data demonstrate that H-PGA binds more immunoglobulins than PGA.

Figure 3. IgG and IgM binding to degraded PGA (H-PGA).

Incubation of human sera with PGA or degraded PGA (H-PGA) resulted in enhanced binding of IgG and IgM to H-PGA. *, P=0.02 compared to PGA. Bars and brackets represent means±SEM for 12 independent experiments.

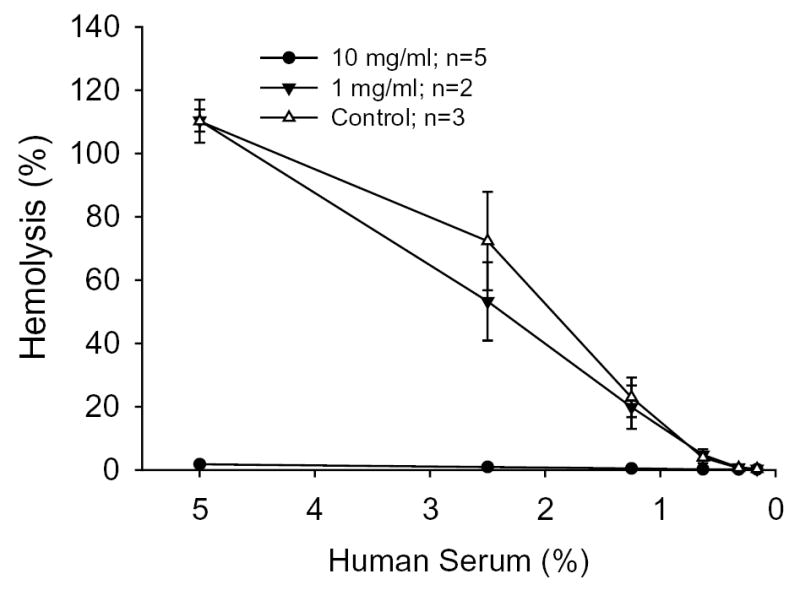

PGA is hydrolyzed to glycolide, so we investigated whether glycolide could activate complement similar to that observed by H-PGA. Glycolide altered the hemolytic activity of human sera in a dose-related manner (Figure 4). At 10 mg/ml, there was essentially no hemolytic activity left in human sera, suggesting that part of the complement activating properties of H-PGA involves the production of glycolide during hydrolysis.

Figure 4. Glycolide Reduces Hemolytic Activity.

A classical hemolytic assay demonstrated that glycolide decreased the hemolytic activity of human sera in a dose-related manner. Untreated serum was used as Control. Each experiment was done in triplicate for n determinations. Symbols and brackets represent means±SEM.

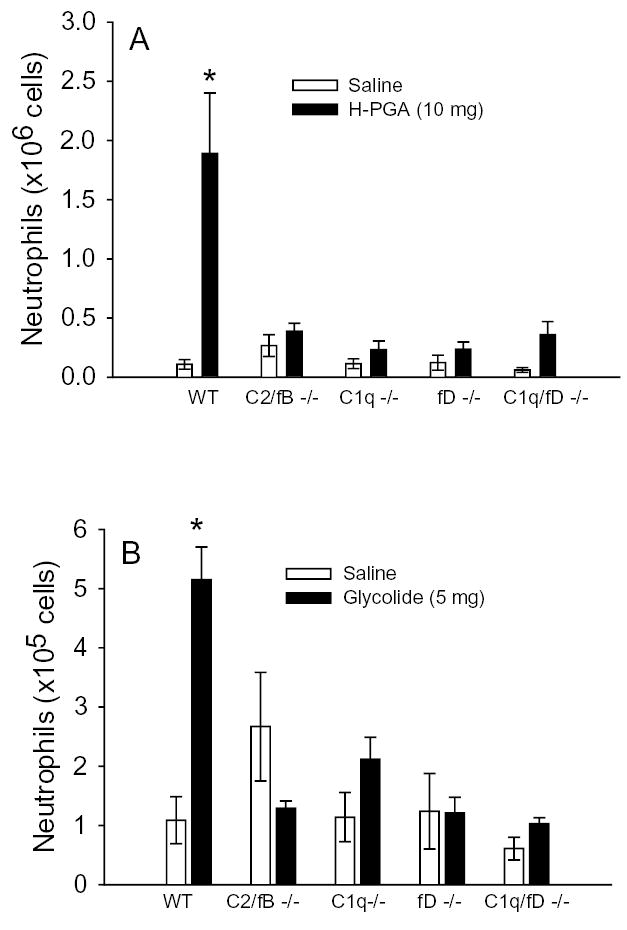

Translation of these in vitro findings to in vivo observations would aid in the discovery of whether complement is activated in vivo and provides the inflammatory signal associated with PGA degradation. Further, the availability of multiple genetically altered mice that lack specific components of the complement system allows examination of whether complement is activated in vivo following intraperitoneal injection of H-PGA and via what pathway. We observed a significant increase in neutrophil sequestration into the peritoneal cavity following H-PGA administration in WT mice compared to saline injected mice (Figure 5A). C2/fB −/− mice, which lack the ability to activate complement via any of the three known complement pathways, did not exhibit increased PMN infiltration compared to WT mice. Furthermore, mice that lacked C1q, factor D or C1q and factor D were also resistant to H-PGA-induced peritonitis. Since the C1q/fD −/− mice only have a lectin pathway, these data suggest that the classical and alternative pathways, but not the lectin pathway, are activated by H-PGA. Further, these data support our in vitro observations using human sera.

Figure 5. H-PGA and Glycolide Induced Peritonitis.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with either saline, degraded PGA (H-PGA,10 mg, Panel A) or glycolide (5 mg, Panel B). Wild type (WT) mice developed peritonitis in response to H-PGA or glycolide (e.g., increased peritoneal neutrophil concentrations). Peritonitis was not observed in C1q −/−, factor D (fD) −/−, C1q and factor D (C1q/fD) −/− or C2 and factor B (C2/fB) −/− mice. Bars and brackets represent means±SEM. *, P<0.05 compared to respective saline control group; n = 4–11 for each group

In order to confirm our in vitro findings and to establish glycolide as a potential mediator for H-PGA induced inflammation observed in Figure 5A, mice were injected with glycolide. We observed a dose-related increase in glycolide-induced PMN recruitment following injection, with 5 mg of glycolide yielding the maximal effect (data not shown). Inflammatory cell recruitment and complement pathway involvement following glycolide (5 mg, i.p.) injection was similar to that observed for H-PGA (Figure 5B vs 5A, respectively). Buffering of the glycolide injectant to pH 7.4 with sodium hydroxide did not alter the results observed in Figure 5B, thus suggesting that glycolide-induced peritonitis was not induced in response to pH changes (data not shown)(27,28)

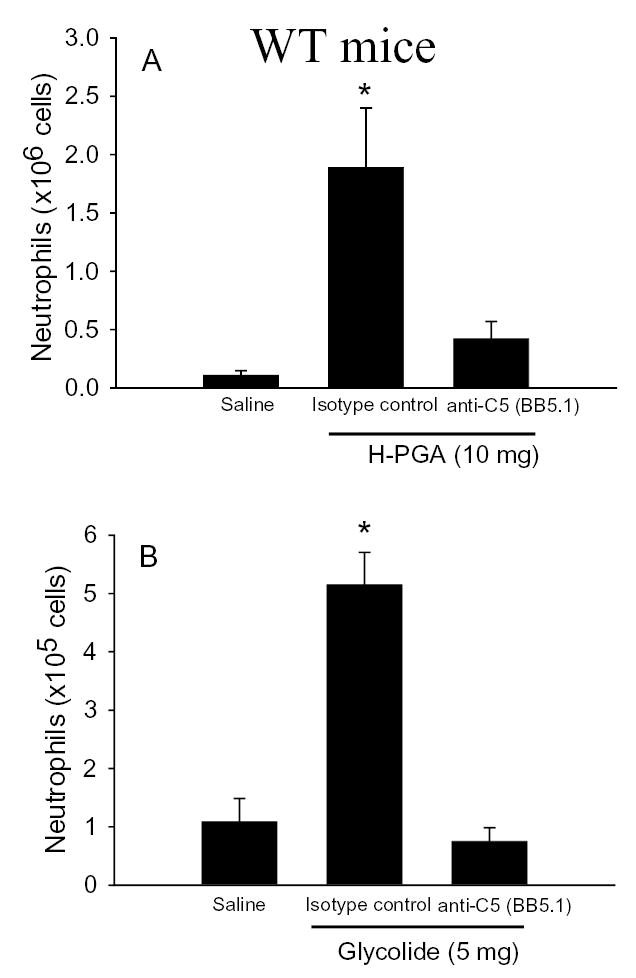

In order to evaluate the role of the early versus late complement components in H-PGA and glycolide induced peritonitis, WT mice were treated with BB5.1 (e.g., inhibition of C5) or an isotype control monoclonal antibody (40 mg/kg) prior to injection with H-PGA or glycolide to inhibit cleavage of C5 (26). Inhibition of C5 eliminated the influx of PMN induced by H-PGA (Figure 6A) or glycolide (Figure 6B). These data suggest that cleavage of C5 is critically involved in the inflammatory response induced by either H-PGA or glycolide. The data also suggest that the early complement components/mediators (e.g., C3a/C3a des Arg) are not involved in the inflammatory response induced by either substance.

Figure 6. Anti-C5 Treatment Attenuates H-PGA- or Glycolide-induced Peritonitis.

Mice were treated with anti-C5 mAb (BB5.1; 40 mg/kg i.p.) or an isotype control mAb one hour before induction of peritonitis with H-PGA (10 mg, i.p., Panel A) or glycolide (5 mg, i.p., Panel B). Anti-C5 mAb significantly attenuated peritonitis induced by either material. *, P<0.05 compared to saline or BB5.1; n=6–11 for each group

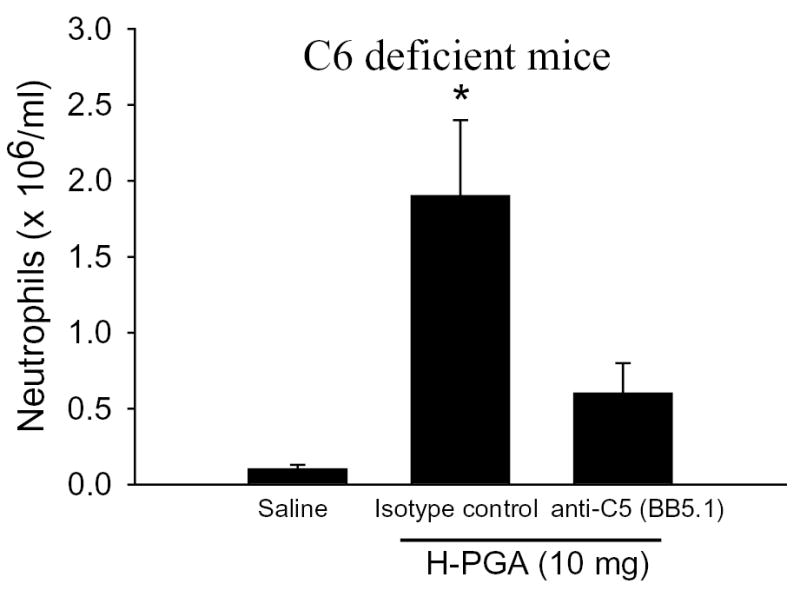

C6 deficient mice lack the ability to form the terminal complement complex (e.g., C5b-9), but still retain the ability to generate the anaphylatoxin, C5a (12). C6 deficient mice treated with an isotype control monoclonal antibody mounted a significant increase in PMN recruitment following injection with H-PGA compared to saline injected mice (Figure 7). Inhibition of C5 with BB5.1 significantly prevented H-PGA-induced peritonitis in the C6 deficient mice, similar to that observed in WT mice (see Figure 6A). These data demonstrate that H-PGA-induced inflammation is mediated by C5a and not by formation of C5b-9.

Figure 7. Role of C5a in H-PGA-induced Peritonitis.

C6 deficient mice were treated with an isotype control mAb or anti-C5 mAb (BB5.1; 40 mg/kg i.p.) one hour before H-PGA-induced peritonitis (10 mg, i.p.). Peritonitis observed in C6 deficient mice was significantly attenuated by anti-C5 mAb. *, P<0.05 compared to saline or BB5.1; n=5–7 for each group

We have previously demonstrated that C6 deficient mice and factor D KO mice do not display decreased PMN function (12,21). In order to rule out an inherent PMN dysfunction in the C1q KO mice being responsible for the decrease inflammation observed in these studies, we induced peritonitis with LTB4 in the C1q KO, C2/fB KO, lectin (C1q/fD KO) and WT mice. As shown in Table 1, LTB4 induced inflammation was not significantly different in any of the groups used in this study and similar to the findings previously observed for C6 deficient and factor D KO mice (12,21).

Table 1.

LTB4 induced inflammation.

| Group (n) | PMN (× 106) |

|---|---|

| WT (n=9) | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| C1q KO (n=5) | 0.8 ± 0.3 |

| C2/fB KO (n=12) | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| Lectin (n=4) | 0.8 ± 1.0 |

There is not significant difference between any of the groups. Lectin = C1q/factor D double KO mouse line; Mean ± SEM

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that polyglycolic acid and other materials being investigated for use in tissue bioengineering can lead to an inflammatory response that is inconsistent with an infectious response (17,29). For example, ~10% of patients treated with rods made of PGA or polylactic acid (PLA) developed an inflammatory response requiring draining and whose drainage consisted of a sterile fluid containing degraded PGA/PLA and inflammatory cells (30,31). In at least one case, plasma samples incubated with PLA demonstrated significantly greater levels of C5a des Arg, a finding that correlates well with the present study using degraded PGA and measuring C5a and C3a synthesis (15). Thus, the clinical use of biodegradable materials appears to be limited by generation of a sterile inflammatory response elicited by biocompatible polymers. While the inflammation observed in these clinical settings may be infrequent and not very severe, inflammation associated with tissue bioengineering can have a more pronounced effect on cell survival and tissue function.

In the present study, we observed that PGA alone does not appear to activate complement in vitro. However, during the degradation of PGA, complement activation occurred, resulting in consumption of complement components and a decrease in the hemolytic activity of the sera following incubation with degraded PGA. We also observed a significant increase in C5a production following incubation of H-PGA in human sera. These in vitro observations correlate well with clinical findings of increased inflammation associated with degradation of PGA rods (30,31) and complement activation associated with degraded PLA pins (15). Further, our study suggests that hydrolysis of PGA activates the classical and alternative pathways. The finding that both pathways play a role in the inflammatory aspects of our study confirms the in vitro findings observations by Harboe et al (22). Further, we extend Harboe et al’s in vitro findings (22) with similar observations in our in vivo peritonitis model. Thus, it appears that once the classical pathway is activated, the alternative pathway is very important in amplifying the complement activation and deposition. We have observed similar findings in our models of gastrointestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury (21). All of these studies highlight the important role of the alternative pathway in amplification of the inflammatory signal after complement is activated.

It is now appreciated that adjuvants containing glycolide polymer microparticles initiate activation of the innate immune system and enable the development of vaccines (32,33). It is likely that natural antibodies may bind to glycolide or smaller degraded portions of PGA and activate the classical pathway, resulting in tick over amplification via the alternative pathway, resulting in C5a production and the inflammatory response. Indeed we observed increased IgG/IgM binding to degraded PGA compared to PGA. Further support for activation of the classical pathway was that inhibition of MBL did not attenuate C5a production following H-PGA incubation in human sera. In contrast, inhibition of C2 or factor D with antibodies attenuated C5a production in H-PGA treated sera. This hypothesis is further supported by the in vivo observations using C1q −/− factor D −/−. Each of these two genotypes resulted in significantly reduced peritonitis, whereas the novel lectin (C1q/fD −/−) mouse, which only has the lectin complement pathway, also did not develop peritonitis to H-PGA injection. Thus, complement inhibition of the classical and/or alternative pathways may represent a therapeutic approach to inhibit inflammation associated during degradation of PGA in vivo.

Previous studies have suggested that inflammation resulting from PGA degradation may be alleviated by incorporation of acid neutralizing salts or antibodies to inhibit the inflammatory response (27,28). However, in our study pH neutralization in glycolide injected mice did not attenuate peritonitis. In contrast, inhibition of complement at the level of C5 in WT mice demonstrated that the terminal complement components mediate the acute inflammatory response to degraded PGA. Further, mice deficient in C6 developed peritonitis to glycolide or H-PGA, suggesting that C5a is the causative agent. Treatment of C6 deficient mice with BB5.1 attenuated peritonitis, further supporting the inflammatory role of C5a in this model. Future studies of matrix implants in C5 deficient mice or WT mice treated with BB5.1 may establish the potential clinical usefulness of complement inhibitors in tissue bioengineering.

Tissue bioengineering holds promise of becoming a safer and cheaper alternative to mechanical devices or organ transplants. However success in this new field is dependent on understanding the inflammatory response that accompanies implantation in non-immunocompromised individuals. The present study suggests that inhibition of the complement component C5a, the classical pathway or the alternative pathway during the time of PGA hydrolysis may circumvent the inflammatory process. Since the matrix is eventually and completely eliminated over time, complement inhibition would only need to take place during the matrix degradation phase. Future studies in complement-inhibited animals following matrix implants will demonstrate the potential clinical usefulness of this therapeutic approach.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health to (HL52886, HL56086, HL63927, DE016191 and DE13499).

Abbreviations used: PGA: polyglycolic acid; neutrophil: PMN; WT: wild type/congenic control; H-PGA: degraded PGA; KO: −/−

References

- 1.Garcia VD, Garcia CD, Keitel E, Santos AF, Bianco PD, Bittar AE, Neumann J, Campos HH, Pestana JO, bbud-Filho M. Expanding criteria for the use of living donors: what are the limits? Transplant Proc. 2004;36:808. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt JL. New directions for organ transplantation. Nature. 1998;392:11. doi: 10.1038/32023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kojima K, Bonassar LJ, Roy AK, Mizuno H, Cortiella J, Vacanti CA. A composite tissue-engineered trachea using sheep nasal chondrocyte and epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2003;17:823. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0462com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kojima K, Bonassar LJ, Roy AK, Vacanti CA, Cortiella J. Autologous tissue-engineered trachea with sheep nasal chondrocytes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:1177. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.121161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vunjak-Novakovic G, Obradovic B, Martin I, Bursac PM, Langer R, Freed LE. Dynamic cell seeding of polymer scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:193. doi: 10.1021/bp970120j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Y, Rodriguez A, Vacanti M, Ibarra C, Arevalo C, Vacanti CA. Comparative study of the use of poly(glycolic acid), calcium alginate and pluronics in the engineering of autologous porcine cartilage. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1998;9:475. doi: 10.1163/156856298x00578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdick JA, Padera RF, Huang JV, Anseth KS. An investigation of the cytotoxicity and histocompatibility of in situ forming lactic acid based orthopedic biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;63:484. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonassar LJ, Sandy JD, Lark MW, Plaas AH, Frank EH, Grodzinsky AJ. Inhibition of cartilage degradation and changes in physical properties induced by IL-1beta and retinoic acid using matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;344:404. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vakeva A, Agah A, Rollins SA, Matis LA, Li L, Stahl GL. Myocardial infarction and apoptosis after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Role of the terminal complement components and inhibition by anti-C5 therapy. Circulation. 1998;97:2259. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wada K, Montalto MC, Stahl GL. Inhibition of complement C5 reduces local and remote organ injury after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:126. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao H, Montalto MC, Pfeiffer KJ, Hao L, Stahl GL. Murine model of gastrointestinal ischemia associated with complement-dependent injury. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:338. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00159.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou W, Farrar CA, Abe K, Pratt JR, Marsh JE, Wang Y, Stahl GL, Sacks SH. Predominant role for C5b-9 in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1363. doi: 10.1172/JCI8621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitch JCK, Rollins SA, Matis LA, Alford BL, Aranki S, Collard CD, Dewar M, Elefteriades J, Hines R, Kopf G, Kraker P, Li L, O'Hara R, Rinder CS, Rinder HM, Shaw R, Smith B, Stahl GL, Shernan SK. Pharmacology and biological efficacy of a recombinant, humanized, single chain antibody, C5 complement inhibitor in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 1999;100:2499. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.25.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friden T, Rydholm U. Severe aseptic synovitis of the knee after biodegradable internal fixation. A case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:94. doi: 10.3109/17453679209154859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tegnander A, Engebretsen L, Bergh K, Eide E, Holen KJ, Iversen OJ. Activation of the complement system and adverse effects of biodegradable pins of polylactic acid (Biofix) in osteochondritis dissecans. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65:472. doi: 10.3109/17453679408995495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rotter N, Ung F, Roy AK et al. Tissue engineering of autologous porcine auricular cardilage: Effect of suerm treatment and role of interleukin-1. Tissue Engineering . 2004.

- 17.Gunatillake PA, Adhikari R. Biodegradable synthetic polymers for tissue engineering. Eur Cell Mater. 2003;5:1. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v005a01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freed LE, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Biron RJ, Eagles DB, Lesnoy DC, Barlow SK, Langer R. Biodegradable polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biotechnology (N Y ) 1994;12:689. doi: 10.1038/nbt0794-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marijnissen WJ, van Osch GJ, Aigner J, van d V, Hollander AP, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL, Verhaar JA. Alginate as a chondrocyte-delivery substance in combination with a non-woven scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1511. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collard CD, Vakeva A, Morrissey MA, Agah A, Rollins SA, Reenstra WR, Buras JA, Meri S, Stahl GL. Complement activation following oxidative stress: Role of the lectin complement pathway. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1549. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stahl GL, Xu Y, Hao L, Miller M, Buras JA, Fung M, Zhao H. Role for the alternative complement pathway in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:455. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63839-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harboe M, Ulvund G, Vien L, Fung M, Mollnes TE. The quantitative role of alternative pathway amplification in classical pathway induced terminal complement activation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collard CD, Vakeva A, Bukusoglu C, Zund G, Sperati CJ, Colgan SP, Stahl GL. Reoxygenation of hypoxic human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) activates the classic complement pathway. Circulation. 1997;96:326. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botto M, Dell'Agnola C, Bygrave AE, Thompson EM, Cook HT, Petry F, Loos M, Pandolfi PP, Walport MJ. Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet. 1998;19:56. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor PR, Nash JT, Theodoridis E, Bygrave AE, Walport MJ, Botto M. A targeted disruption of the murine complement factor B gene resulting in loss of expression of three genes in close proximity, factor B, C2, and D17H6S45. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao H, Montalto MC, Pfeiffer KJ, Hao L, Stahl GL. Murine model of gastrointestinal ischemia associated with complement dependent injury. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:338. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00159.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agrawal CM, Athanasiou KA. Technique to control pH in vicinity of biodegrading PLA-PGA implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;38:105. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199722)38:2<105::aid-jbm4>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bostman O, Pihlajamaki H. Clinical biocompatibility of biodegradable orthopaedic implants for internal fixation: a review. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2615. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Athanasiou KA, Niederauer GG, Agrawal CM. Sterilization, toxicity, biocompatibility and clinical applications of polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid copolymers. Biomaterials. 1996;17:93. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bostman OM. Intense granulomatous inflammatory lesions associated with absorbable internal fixation devices made of polyglycolide in ankle fractures. Clin Orthop. 1992;193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bostman O, Hirvensalo E, Makinen J, Rokkanen P. Foreign-body reactions to fracture fixation implants of biodegradable synthetic polymers. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:592. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B4.2199452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferro VA, Costa R, Carter KC, Harvey MJ, Waterston MM, Mullen AB, Matschke C, Mann JF, Colston A, Stimson WH. Immune responses to a GnRH-based anti-fertility immunogen, induced by different adjuvants and subsequent effect on vaccine efficacy. Vaccine. 2004;22:1024. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carcaboso AM, Hernandez RM, Igartua M, Rosas JE, Patarroyo ME, Pedraz JL. Enhancing immunogenicity and reducing dose of microparticulated synthetic vaccines: single intradermal administration. Pharm Res. 2004;21:121. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000012159.20895.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]