Abstract

A 40 year old man with hereditary multiple exostoses (HME), affecting predominantly his left proximal tibia, distal femur, and proximal femur, underwent resection of an osteochondroma near the trochanter major of his left proximal femur because of malignant transformation of the cartilaginous cap towards secondary peripheral chondrosarcoma. The patient had a history of a papillary thyroid carcinoma four years previously. At examination of the resected specimen, a third malignant tumour, an intermediate grade osteosarcoma (grade II/IV), was found in the osseous stalk of the osteochondroma. Although no mutations were found in the EXT1 and EXT2 genes, the genes involved in HME, or in exons 5–8 of the p53 gene, the development of three malignancies before the age of 40 suggests that this patient is genetically prone to malignant transformation.

Keywords: osteochondroma, hereditary multiple exostoses, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma

Hereditary multiple exostoses (HME) is an autosomal dominant skeletal disorder characterised by the development of multiple osteochondromas (osteocartilaginous exostoses), resulting in a variety of orthopaedic deformities. HME is genetically heterogeneous, and two genes, EXT1 located at 8q24 and EXT2 located at 11p11–p12, have been characterised.1–3 Osteochondroma has been shown to be a neoplastic disorder, documented by loss of heterozygosity at the EXT1 locus, DNA aneuploidy, and clonal karyotypic abnormalities.4 The most serious complication is malignant transformation. The risk of developing a malignant tumour is estimated to be less than 5% in HME. Malignant transformation leads to a chondrosarcoma in 94% of these cases, and this has been shown to occur by subsequent additional genetic alterations. Osteosarcomas, fibrosarcomas, and malignant fibrous histiocytomas are encountered infrequently.

We present an unusual case of a patient with HME, who had a resection of an osteochondroma near the trochanter major of his left proximal femur demonstrating a secondary chondrosarcoma in the cartilaginous cap, in addition to an intermediate grade osteosarcoma in the stalk of the same osteochondroma.

CLINICAL HISTORY

In February 1995, a 40 year old man presented with recurrent pain in the greater trochanter of his left femur. The patient had a history of a papillary thyroid carcinoma four years previously (fig 1A) and was known to have HME. Family history revealed multiple bony lesions in one of his two children, his father, and a nephew. Skeletal scintigraphy had demonstrated multiple active lesions.

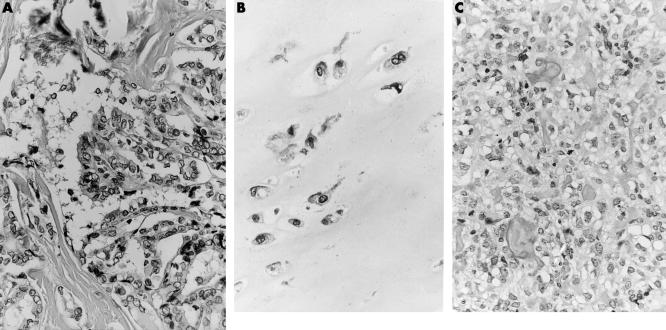

Figure 1.

(A) Light micrograph of the papillary thyroid carcinoma that was removed four years previously. (B) Light micrograph of the cartilaginous cap, displaying widely spaced, pronounced atypical, binucleated chondrocytes. (C) Light micrograph of a histologically distinct area present within the stalk of the tumour. This area is composed of an admixture of moderately pleomorphic tumour cells with the formation of a trabecular deposited osteoid. Note the presence of a mitotic figure.

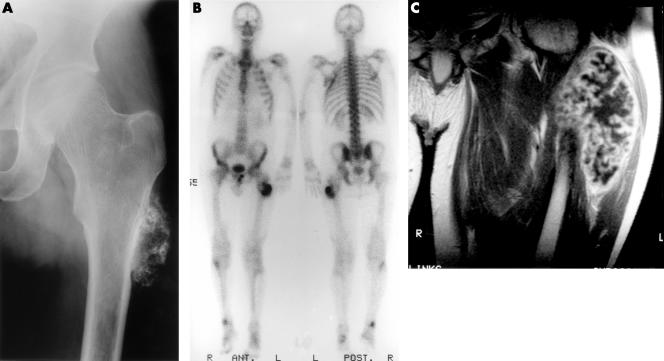

At presentation a large (14 × 9 cm), firm, and slightly tender mass was palpated near the left trochanter major. The tissue mass seemed to be attached to the bone. The patient had been seen three years before for similar symptoms. Radiography, bone scintigraphy, and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging at that time revealed no indications for malignant transformation of the cartilaginous cap (fig 2A). Although repeated radiography in 1995 did not show a significant change in the lesion, increased activity was seen at bone scintigraphy when compared with the previous scan (fig 2B). MR imaging (fig 2C) showed that the lesion had grown to a size of 7 × 9 × 11 cm. After intravenous contrast administration a septal and nodular enhancement pattern was seen, suggesting progression towards secondary peripheral chondrosarcoma. A Jamshidi trocar biopsy revealed irregularly distributed chondrocytes and binucleated cells, confirming malignant transformation.

Figure 2.

(A) An anterior-posterior radiograph of the left femur, taken three years before presentation (at age 37), displays ring-like and amorphous calcifications in the soft tissues. The normal cortex is continuous with the lesion. (B) Bone scintigraphy at presentation at age 40 displays focally increased accumulation of radiotracer. This was found predominantly at the site of the grade II osteosarcoma, located in the stalk of the osteochondroma. (C) On T1 weighted images after intravenous injection of gadolineum–DTPA a uniform septal and nodular enhancement of the tumour is seen.

Subsequently, the patient was admitted for surgery. At operation, the exophytic tumour was excised en bloc with the biopsy scar and a layer of soft tissue. At the femoral site the stalk of the tumour was taken out with a part of the lateral femur and greater trochanter. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen showed the classic appearance of an osteochondroma, with a cartilaginous cap measuring about 7 cm in thickness, microscopically consistent with a grade I chondrosarcoma (fig 1B). Both macroscopically and microscopically a distinct, mainly circumscribed lesion measuring 2 cm was observed within the osseous stalk of the osteochondroma, which microscopically appeared to be an intermediate grade osteosarcoma (grade II/IV) (fig 1C). All resection margins were free of tumour. More than four years later the patient is well and free of disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA isolation

DNA isolation from fresh frozen tissue of the secondary chondrosarcoma component was performed as described previously.5 Normal DNA was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes of the same patient using a salting out procedure.6 DNA isolation from the formalin fixed, grade II osteosarcoma component failed to yield appropriate DNA owing to decalcification procedures.

EXT1 and EXT2 mutation analysis

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and single strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analyses of all EXT1 and EXT2 exons were performed on chondrosarcoma tumour DNA as detailed previously,4 and gel patterns were compared with other chondrosarcoma tumour samples.

p53 analysis

Immunohistochemical reactions using monoclonal antibodies directed against p53 (clone DO-7; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) were performed on formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded tissue from the papillary thyroid carcinoma, the grade II osteosarcoma, and the grade I chondrosarcoma according to standard laboratory methods.7

Mutation analysis was performed using PCR and direct sequencing of exons 5 to 8 on both normal and chondrosarcoma tumour DNA as described previously.8

RESULTS

EXT1 and EXT2 mutation analysis

Although our patient had a positive family history for multiple exostoses, no aberrant bands were detected in the EXT1 and EXT2 genes by SSCP.

p53 analysis

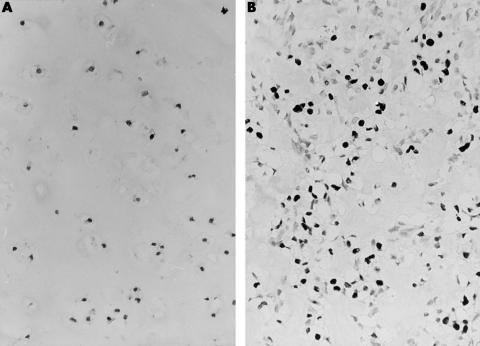

Both the papillary thyroid carcinoma and the chondrosarcoma failed to show p53 immunoreactivity, whereas the grade II osteosarcoma showed p53 overexpression (fig 3). Both in normal DNA and in chondrosarcoma tumour DNA, no mutations were found in exons 5 to 8 of p53 by direct sequencing. Unfortunately, no appropriate DNA was available from the grade II osteosarcoma showing p53 overexpression, so a possible somatic mutation could not be demonstrated.

Figure 3.

The chondrosarcoma is negative for p53 (A), whereas the grade II osteosarcoma shows p53 overexpression (B).

DISCUSSION

The patient described came from a family known to be affected by HME. HME is an autosomal dominant, genetically heterogeneous disorder, with an incomplete penetrance mostly in females. Two genes, EXT1 and EXT2, have been cloned to date.1–3 Recently, the EXT1 and EXT2 genes were shown to be tumour suppressor genes.4 The gene products are glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of cell surface heparan sulphate,9 affecting diffusion of the morphogen Hedgehog.10 Linkage to chromosome 19p has also been found, suggesting the existence of an EXT3 gene.11

Malignant transformation of osteochondroma is estimated to occur in 1–5% of cases of HME. The suspicion of secondary chondrosarcoma is indicated by growth of the tumour after puberty, the presence of pain, or a thickness over 1 cm of the cartilaginous cap in adults. At present, the size of the cartilaginous cap can be well established with T2 weighted MR imaging. In our case, there was no doubt about the extensive presence of hyaline cartilage nodules as displayed by high signal intensity on the T2 weighted MR images in a lobular fashion, separated by low signal intensity septations.

The process of malignant transformation of osteochondroma is genetically represented by chromosomal instability, as was previously demonstrated by a high percentage of loss of heterozygosity involving various loci and a broad range of DNA ploidy.7 The chondrosarcoma of our patient demonstrated near haploidy (DNA index, 0.56) and loss of heterozygosity for most chromosomes tested.12 At the protein level, malignant transformation is characterised by upregulation of the expression of parathyroid hormone releasing protein and Bcl-2, two putative downstream effectors of EXT, which are normally involved in a delicate paracrine feedback loop in the growth plate.13

Secondary osteosarcoma is extremely rare and only a few cases have been reported in the literature.14 Unexpectedly, an intraosseous grade II osteosarcoma was found in the stalk of the osteochondroma of our patient. Intraosseous low grade (grade I–II) osteosarcomas comprise approximately 1% of all osteosarcomas. The duration of symptoms can be long and some patients are even asymptomatic. Patients treated with wide resection of a low grade osteosarcoma seem to have a good prognosis, with almost no chance of recurrence. Because the margins of the resected specimen from our patient were free of tumour the operation was considered adequate for both the chondrosarcoma and the osteosarcoma.

“The suspicion of secondary chondrosarcoma is indicated by growth of the tumour after puberty, the presence of pain, or a thickness over 1 cm of the cartilaginous cap in adults”

In the differential diagnosis one could consider dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma secondary to osteochondroma in this case. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma is defined as a high grade anaplastic sarcoma, next to a low grade malignant cartilaginous tumour. However, first, the osteosarcomatous part was situated in the stalk of the original osteochondroma separately from the cartilaginous cap comprising the chondrosarcoma. In dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma, the anaplastic component emerges from the low grade chondrosarcomatous part. Second, in our present case the osteosarcomatous part was a low to intermediate grade, whereas the anaplastic component of a dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma usually has a high grade appearance.

The development of three separate malignancies before the age of 40 in our patient is highly unusual, and suggests that he is genetically prone to malignant transformation. We expected an EXT germline mutation to be present in our patient. Both the EXT1 and EXT2 genes, which have been reported to show linkage in about 70% of the HME families, were screened for mutations. However, we found no aberrant bands by SSCP analysis, either because of the relatively low sensitivity of SSCP mutation analysis (70–90%), or because another (EXT) gene is responsible for the phenotype of our patient. A candidate would be the putative EXT3 gene on chromosome 19p. Interestingly, the occurrence of familial thyroid tumours was linked to 19p13.2,15 raising the possibility of a contiguous gene deletion syndrome at 19p in our patient.

Take home messages.

The development of three separate malignancies before the age of 40 in our patient suggests that he is genetically prone to malignant transformation

However, no mutations were found in the EXT1 and EXT2 genes, the genes involved in HME, or in the p53 gene

Osteosarcoma can rarely arise secondary to osteochondrosarcoma

However, it must be noted that even in the presence of a constitutional EXT mutation, the development of three malignancies is highly unusual. Although the family history did not indicate the presence of a Li-Fraumeni (-like) syndrome, we investigated the p53 gene, which is known to cause a variety of cancers at a young age when mutated in the germline.16 p53 overexpression was restricted to the grade II osteosarcoma. We found no mutations in exons 5–8, the exons bearing 87% of the mutations found in p53.

In conclusion, we present the unusual case of a patient with HME who had a secondary chondrosarcoma in the cartilaginous cap and an intermediate grade osteosarcoma in the stalk of an osteochondroma. In addition, the patient had a history of a papillary thyroid carcinoma four years previously. Although no mutations were found in the genes involved in HME, or in the p53 gene, the development of three malignancies before the age of 40 suggests that this patient is genetically prone to malignant transformation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank LJCM van den Broek and AM Kersenmaekers for expert technical assistance, Dr AM Cleton-Jansen and Professor CJ Cornelisse for helpful discussions, and Dr W van Hul, University of Antwerp, for performing the EXT2 mutation analysis.

Abbreviations

HME, hereditary multiple exostoses

MR, magnetic resonance

PCR, polymerase chain reaction

SSCP, single strand conformational polymorphism

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn J, Ludecke H-J, Lindow S, et al. Cloning of the putative tumour suppressor gene for hereditary multiple exostoses (EXT1). Nat Genet 1995;11:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stickens D, Clines G, Burbee D, et al. The EXT2 multiple exostoses gene defines a family of putative tumour suppressor genes. Nat Genet 1996;14:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wuyts W, Van Hul W, Wauters J, et al. Positional cloning of a gene involved in hereditary multiple exostoses. Hum Mol Genet 1996;5:1547–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bovee JVMG, Cleton-Jansen AM, Wuyts W, et al. EXT-mutation analysis and loss of heterozygosity in sporadic and hereditary osteochondromas and secondary chondrosarcomas. Am J Hum Genet 1999;65:689–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devilee P, Van den Broek M, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn N, et al. At least four different chromosomal regions are involved in loss of heterozygosity in human breast carcinoma. Genomics 1989;5:554–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller SA, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 1988;16:1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bovee JVMG, Cleton-Jansen AM, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn N, et al. Loss of heterozygosity and DNA ploidy point to a diverging genetic mechanism in the origin of peripheral and central chondrosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1999;26:237–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bovee JVMG, Cleton-Jansen AM, Rosenberg C, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of both components of a dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma, with implications for its histogenesis. J Pathol 1999;189:454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCormick C, Leduc Y, Martindale D, et al. The putative tumour suppressor EXT1 alters the expression of cell-surface heparan sulfate. Nat Genet 1998;19:158–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellaiche Y, The I, Perrimon N. Tout-velu is a drosophila homologue of the putative tumour suppressor EXT1 and is needed for Hh diffusion. Nature 1998;394:85–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Merrer M, Legeai-Mallet L, Jeannin PM, et al. A gene for hereditary multiple exostoses maps to chromosome 19p. Hum Mol Genet 1994;3:717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bovee JVMG, van Royen M, Bardoel AFJ, et al. Near-haploidy and subsequent polyploidization characterize the progression of peripheral chondrosarcoma. Am J Pathol 2000;157:1587–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bovee JVMG, Van den Broek LJCM, Cleton-Jansen AM, et al. Up-regulation of PTHrP and Bcl-2 expression characterizes the progression of osteochondroma towards peripheral chondrosarcoma and is a late event in central chondrosarcoma. Lab Invest 2000;80:1925–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamovec J, Spiler M, Jevtic V. Osteosarcoma arising in a solitary osteochondroma of the fibula. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1999;123:832–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harach HR, Lesueur F, Amati P, et al. Histology of familial thyroid tumours linked to a gene mapping to chromosome 19p13.2. J Pathol 1999;189:387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Mulvihill JJ, et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res 1988;48:5358–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]