Abstract

Aims: To assess the constancy of the histological grade of invasive breast carcinomas by comparing primary tumours with their axillary metastases and local or regional recurrences.

Methods: Eighty four recurrent invasive breast carcinomas with a primary tumour or previous recurrence were available for histological review from the period 1980 to 2000. These and any further recurrences were graded by one observer.

Results: Nine, 24, and 51 tumours with grades 1, 2, and 3, respectively, recurred. Grade 1, 2, and 3 tumours recurred within a median time of 88, 42, and 23 months, respectively. The intraobserver reproducibility of the histological grade was good (κ = 0.66), and the grades of the primary tumours and their axillary metastases or next recurrence also exhibited good agreement. However, when further (second to sixth) recurrences were included in the analysis, the agreement between the grade of the tumours and their last recurrence was only moderate (κ = 0.48). Only two of the nine grade 1 and 15 of the 24 grade 2 tumours retained their grade in their last recurrence.

Conclusions: Low grade carcinomas require a longer follow up. These long term data support the possibility of a transition from low grade invasive breast carcinomas to higher grade tumours. It is suggested that low grade (well differentiated) breast carcinomas are not a single entity: some may progress to high grade tumours, whereas others appear not to progress.

Keywords: breast cancer, histological grade, recurrent cancer, tumour progression

A lthough several steps of carcinogenesis have already been explored, the development of malignant tumours is not fully understood. The currently available data demonstrate that the development of malignant tumours requires the presence of several genetic lesions and/or epigenetic factors, and their development involves progression. In breast cancer, the morphologically identifiable steps of this progression include atypical ductal hyperplasia (with a fivefold increase in relative risk of breast cancer),1 ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (a lesion considered an obligate precursor of invasive cancer, with at least a 10 fold increase in relative risk of the development of the latter),1 and invasive carcinoma. Earlier steps may include typical ductal hyperplasia, especially its florid variant,2 which does not usually progress to cancer, or certain histologically unidentifiable lesions, which already carry genetic predisposing lesions, as suggested by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) studies.3 Great care must be taken in the interpretation of these results because normal epithelium of the breast also seems monoclonal by LOH analysis.4 At the other end of the spectrum, there are also unanswered questions relating to the progression of invasive cancers.

The systemic theory formulated by Fisher postulates that invasive breast cancer is a systemic disease from its beginning.5 However, the opposing locoregional theory put forward earlier by Halsted6 also has some truth. Both the mortality decrease resulting from early detection as a consequence of breast cancer screening,7, 8 and the relatively high proportion of patients with breast cancer cured with locoregional treatment alone,9–11 favour the spectrum theory12 and the progressive nature of breast cancer. It is well accepted that breast cancer is not a single disease; as an example, well differentiated carcinomas have better outcomes than poorly differentiated carcinomas of the same size and nodal status. It remains unclear whether high grade (poorly differentiated) carcinomas develop from low grade carcinomas, as suggested by some studies,13–15 or are derived directly from high grade DCIS, as suggested by others.2, 16–18 In our present study, invasive carcinomas with subsequent recurrences were studied with respect to their histological grade, to evaluate the constancy of this prognostic parameter.

“The mortality decrease resulting from early detection, and the relatively high proportion of patients with breast cancer cured with locoregional treatment alone, favour the spectrum theory and the progressive nature of breast cancer”

METHODS

Locally or regionally recurrent invasive breast tumour specimens assessed between January 1980 and December 2000 were identified from the hard copy (1980–1997) and electronic (1998–2000) files at the department of pathology of the Bács-Kiskun County Teaching Hospital. The basis of the analysis was formed by those recurrent invasive carcinomas for which either the primary tumour or (in the absence of a primary tumour assessed between 1980 and 2000) a previous recurrence was available for histopathological review from the same period. Only ipsilateral recurrences were taken into consideration. Several of the patients had multiple metachronous recurrences. Recurrences were ranked according to the time of their appearance. For the few cases with simultaneous local and axillary recurrence, the local recurrence was thought to precede the regional one. The time between the recurrences in these cases was set at 0 months. In general, the time to recurrence was defined as the number of months that elapsed between the two operations in which the given specimens were removed. The primary tumours had been treated surgically by mastectomy or quadrantectomy and complete or level I and II axillary dissection, on occasion complemented with radiotherapy and adjuvant systemic treatment, depending on the tumour and patient parameters.

Because the data on the tumours were not always complete in the initial part of the period investigated, and the tumour sizes were often given as comparative sizes rather than as measured values, the tumours were systematically assigned to a T category in an earlier study.19 This was done to match the estimated clinical T category of the TNM system.20 Because breast cancer screening was initiated in our region only in 1999, most of the assessed tumours were symptomatic.

All specimens were originally fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. Original slides were re-evaluated and their histological grades21, 22 were determined by the author. The investigator was blind to the origin of the specimens.

The determination of histological grade involves subjective elements. Accordingly, κ statistics23 were also performed to assess the agreement between the grades of the primary tumours and their recurrences. A great advantage of this type of analysis is that it is independent of the “real” grade of the cancer; it simply assesses the constancy or lack of constancy of the given parameter. The following arbitrary limits and labels were used to interpret agreement on the basis of the κ values: < 0.00, poor; 0.00–0.20, slight; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial; and 0.81–1.00, very good.24 Independently, 50 breast carcinoma specimens were graded by the author at three different times to check the intraobserver reproducibility of the histological grading. All gradings were performed with the inspection of all slides from the given tumour.

RESULTS

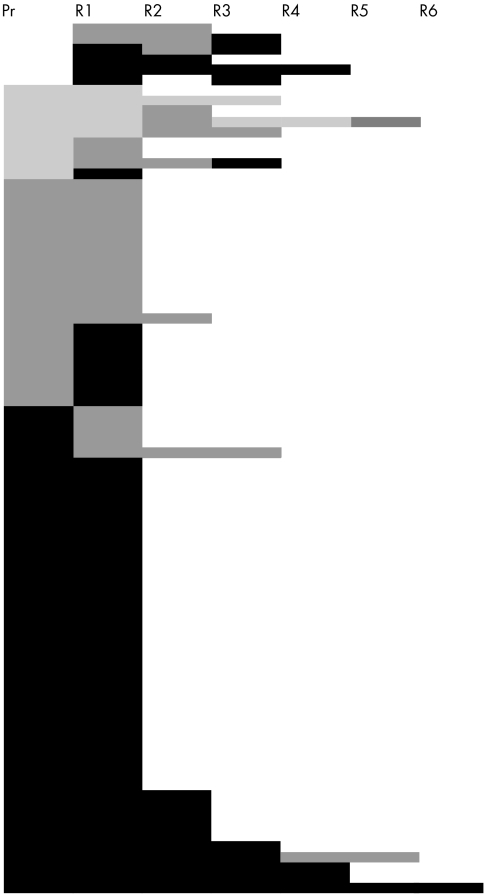

Eighty four patients with locally or regionally recurrent breast carcinomas, for whom data on either primary (n = 78) (table 1) or previous recurrent tumours (n = 6) (further referred to as baseline tumours) and subsequent recurrences were available were reviewed (fig 1). In the case of the six neoplasms with only a previous recurrence accessible, the primary carcinoma was either diagnosed before 1980 or was operated on at another institution because the patient moved from one town to another; the slides of the primary cancers were therefore not available for review, but at least two metachronous recurrences could be compared. The material of a second recurrence of a tumour with three metachronous recurrences but no primary neoplasm identified in our inspected files was lost, and therefore it is represented in fig 1 (row 6), but is missing from the R2→R3 column of table 2. It should be noted that the number of node negative cases in this population might have been overestimated because the number of lymph nodes assessed in the very early part of the period was suboptimal, as described previously.19 The mean and median age of the patients at diagnosis of the primary tumours was 58 years (range, 30–84). The histological grade of the baseline tumours was 1, 2, and 3 in nine, 24, and 51 cases, respectively. Grade 1, 2, and 3 tumours recurred within a median time of 88, 42, and 23 months, respectively.

Table 1.

T category and nodal status of the primary tumours involved in this study

| Nodal status | ||||

| T category | Unknown | Node negative | Node positive | Total |

| Unknown | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| T1 | 5 | 11 | 13 | 29 |

| T2 | 1 | 9 | 22 | 32 |

| T3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| T4 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| Total | 10 | 23 | 45 | 78 |

Figure 1.

Changes in the histological grades of the tumours assessed. Each tumour is represented by one row and the worsening grades by darker tones. Pr, primary; R, recurrence.

Table 2.

Comparison of grades of baseline tumours, their axillary metastases and consecutive recurrences

| Pr→R1 | Pr→Ax | R1→R2 | R2→R3 | R3→R4 | R4→R5 | R5→R6 | Baseline→Last R | |

| G1→G1 | 5 (56%; 31; 12–103) | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%; 15) | 1 (100%; 40) | 1 (100%; 16) | 0 | 0 | 2 (22%; 78; 12–143) |

| G1→G2 | 3 (33%; 95; 44–200) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%; 8; 0–77) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%; 39) | 0 | 5 (56%; 104; 28–200) |

| G1→G3 | 1 (11%; 168) | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (22%; 145; 122–168) |

| G2→G1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%; 18) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| G2→G2 | 14 (64%; 49; 4–100) | 9 (75%) | 5 (100%; 17; 7–54) | 2 (33%; 0) | 0 | 1 (100%; 0) | 0 | 15 (63%; 47; 4–100) |

| G2→G3 | 8 (36%; 36; 19–122) | 3 (25%) | 0 | 3 (50%; 7; 6–24) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (37%; 36; 19–122) |

| G3→G1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| G3→G2 | 5 (11%; 20; 9–77) | 3 (11%) | 1 (8%; 4) | 0 | 1 (20%; 0) | 0 | 0 | 6 (12%; 25; 9–77) |

| G3→G3 | 42 (89%; 23; 4–230) | 24 (89%) | 12 (92%; 13; 1–64) | 6 (100%; 7; 0–19) | 4 (80%; 14; 8–19) | 1 (100%; 5) | 1 (100%; 28) | 45 (88%; 28; 4–230) |

The first values are the absolute numbers of tumours exhibiting the given grades. The figures in parentheses are the percentages of the total number of tumours with the same initial grade, followed by the times to recurrence, in months (median; range).

Ax, axillary metastasis; G, grade; Last R, last recurrence; Pr, primary tumour; R1–6, first to sixth recurrence.

Changes in grades for baseline tumours, axillary metastases, and consecutive recurrences are given in table 2, which also includes data on the grades of the tumours as first and last seen. Tables 3 and 4 show the changes in the individual components of the histological grade for the baseline tumours and their last recurrence.

Table 3.

Data on baseline tumours and their last recurrence scored for the presence of tubules, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic rate

| Baseline score recurrence score | Tubules | Pleomorphism | Mitoses |

| 1-1 | 2 (40%) | 1 (25%) | 11 (46%) |

| 1-2 | 2 (40%) | 2 (50%) | 9 (38%) |

| 1-3 | 1 (20%) | 1 (25%) | 4 (17%) |

| 2-1 | 1 (4%) | 0 | 2 (11%) |

| 2-2 | 14 (58%) | 11 (69%) | 3 (17%) |

| 2-3 | 9 (38%) | 5 (31%) | 13 (72%) |

| 3-1 | 0 | 0 | 4 (10%) |

| 3-2 | 2 (4%) | 5 (8%) | 7 (17%) |

| 3-3 | 53 (96%) | 59 (92%) | 31 (74%) |

Values in parentheses are the percentages of all tumours with the same baseline score for the given parameter.

Table 4.

Changes in score for baseline tumours and their last recurrence, scored for the presence of tubules, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic rate

| Change in score | Tubules | Pleomorphism | Mitoses |

| Decreased | 3 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 13 (15%) |

| No change | 69 (82%) | 71 (85%) | 45 (54%) |

| Increased | 12 (14%) | 8 (10%) | 26 (31%) |

Values in parentheses are the percentages of all (n=84) tumours.

The intraobserver variability in the assessment of the histological grade resulted in an overall κ value of 0.66 (SE = 0.06)—substantial reproducibility. Grades 1, 2, and 3 had κ values of 0.67, 0.6, and 0.72 (SE = 0.08), respectively, with the reproducibility of grade 2 just falling in the moderately reproducible category.

Table 5 gives the κ values for the agreement between the grade of the baseline tumours and their next recurrence (n = 84), last recurrence (n = 84), and axillary metastasis (n = 43 node positive cases). The κ values for the grades of the primary tumours and their axillary metastases, and those for the grades of the baseline tumours and their next recurrences, are close to the κ values for the intraobserver reproducibility of the histological grade. In contrast, the κ values for the grades of the tumours and their last recurrence all fall into a lower category, reflecting a decrease in agreement.

Table 5.

κ Values and their standard errors (and the agreement reflected by these values) for the agreement of the histological grades of baseline tumours and their axillary metastases, and their next and last recurrence

| κ Values for | Pr–Ax | Baseline–Next R | Baseline–Last R |

| Grade 1 | 0.64 (0.15) | 0.69 (0.11) | 0.31 (0.11) |

| (substantial) | (substantial) | (fair) | |

| Grade 2 | 0.61 (0.15) | 0.51 (0.11) | 0.43 (0.11) |

| (substantial) | (moderate) | (moderate) | |

| Grade 3 | 0.65 (0.15) | 0.62 (0.11) | 0.56 (0.11) |

| (substantial) | (substantial) | (moderate) | |

| Overall | 0.63 (0.13) | 0.59 (0.09) | 0.48 (0.09) |

| (substantial) | (moderate) | (moderate) | |

Ax, axillary metastasis; G, grade; Last R, last recurrence; Next R, next recurrence; Pr, primary tumour.

DISCUSSION

The progression of low grade invasive carcinomas to higher grade tumours is suggested by the results of screening studies.7 A relation between larger tumour size and higher grade has also been described.13, 15. It has been proposed that small tumours discovered only on mammographic screening are more commonly of lower grade than symptomatic cancers; with time, small tumours worsen with regard to their grade of malignancy.14 The tubular–tubuloductal carcinoma classification system of a large group of breast cancers, put forward by Linell and Ljundberg,25 similarly supports this concept. Tumours that we would now call well or, at most, moderately differentiated on the basis of tubule formation were consistently smaller than carcinomas with diminishing tubule formation and increasing solid tumour component.25 The importance of distinguishing a histological type of breast carcinoma with prognosis and histological features between tubular and ductal carcinomas of no special type26–28 also seems to support the possibility of a progression in grade of invasive breast carcinomas. Indeed, tubular mixed carcinoma is generally a grade 2 cancer with a grade 1 central area and a higher grade periphery, suggesting dedifferentiation within a single tumour with heterogeneous features.

In addition, it has also been postulated that low grade invasive breast carcinomas develop from low grade DCIS, whereas poorly differentiated cancers are derived from high grade DCIS. This theory is supported by the finding of a concordant grade DCIS component in most invasive cancers.29–31 Cytogenetic alterations may be so characteristic in DCIS that their presence has been proposed as an adjunct to be included in new classification schemes of the disease.32 The finding of a common genetic lesion identified with comparative genomic hybridisation in most low grade invasive carcinomas (loss of 16q), and missing from most high grade invasive cancers, also favours this last theory because regaining an already acquired oncogenic lesion during tumour progression is very unlikely.17, 18 Morphometric nuclear studies lend further support to a different route of progression for low and high grade tumours.2

Poorly differentiated tumours in this series recurred more frequently and within a shorter time than did moderately or well differentiated tumours, and the well differentiated tumours were those that recurred least often and with the longest time to recurrence. This is in accord with long term follow up data on patients with breast cancer,33 which suggest that the ultimate outcome of low grade breast carcinomas should be assessed on the basis of a long term (10 to 20 year) follow up, because metastases in these low “virulence” tumours are manifested only later, and the death from disease curves may therefore level off later than for poorly differentiated carcinomas.

“Morphometric nuclear studies lend further support to a different route of progression for low and high grade tumours”

The histological grade of breast carcinoma21, 22 is a composite prognostic factor with confirmed prognostic value.21, 34, 35 In contrast to time related factors, such as tumour size and probably nodal stage, it reflects tumour aggressiveness. Its determination involves subjective elements, especially concerning the scoring of nuclear pleomorphism. The sampling of the tumour tissue may also affect the score given for any of the variables, especially in tumours with mixed features. Despite these reservations, the determination of histological grade has been shown to be reproducible.36, 37 Not only interobserver, but also intraobserver variability may arise, and this could influence the interpretation of the results of this study; accordingly the intraobserver reproducibility was evaluated and was found to be good.

It was found that low and intermediate grade carcinomas often recur as higher grade tumours. This phenomenon was encountered in 16 low or intermediate grade tumours. The opposite phenomenon—higher grade tumours recurring as better differentiated ones—was seen only rarely, and only in connection with six grade 3 tumours recurring as grade 2 carcinomas. The downgrading of subsequent (recurrent) tumours could in theory be a result of several factors; as shown in table 3, the lower scores for the mitotic rate in the recurrent tumours might be the principal cause. Indeed, all six tumours that recurred with a lower grade had a lower mitotic rate score in the recurrence than in the primary. Apart from mitotic score variations as a result of sampling variations, the factors initiating or influencing mitoses might have been different at the time of subsequent operations. Of the factors determining the combined histological grade, the mitotic scores were the least stable. Table 3 reveals that changes in all scores contributed to a worsening of the histological grade.

As a possible means of assessing tumour progression, we also analysed axillary metastases whenever they were present and tissue specimens were available for this purpose. A worsening of the malignancy grade was seen in two of four grade 1 tumours and in three of 12 grade 2 tumours, whereas only three of 27 grade 3 tumours gave grade 2 regional metastases; no other examples of histological grade regression were encountered. These values could point to a progression in grade. However, the κ values for the grades of these tumours did not reflect a lack of constancy, and were very similar to the results of an earlier study at Guy's Hospital in London, in which 102 metastases were compared with their primary carcinoma.16 Theoretically, metastases are formed by tumour cells that have acquired all the qualities necessary for this,38 and they therefore represent progressed tumour cells in comparison with the cancer cells of a non-metastatic or in situ carcinoma. When a primary tumour has achieved the propensity to form metastases, however, it will not necessarily display a different grade from that of its own metastasis. Our results indicate a relative similarity between the grade of a primary breast cancer and that of its axillary metastasis. The similarity of metastases and primary tumours is likewise often a confirmatory finding in diagnostic histopathology, demonstrating that the metastasis really is derived from the given primary. Our data on axillary metastases and their primary tumours are therefore not self evident in relation to tumour progression, and the limited number of node positive cases in the study limits the drawing of conclusions from the grade of differentiation of axillary metastases.

Take home messages .

Patients with low grade carcinomas require a longer follow up because metastases manifest later in this group of patients

The long term data support the possibility of a transition from low grade invasive breast carcinomas to higher grade tumours

It is possible that low grade (well differentiated) breast carcinomas are not a single entity: some may progress to high grade tumours, whereas others appear not to progress

Although the number of low grade tumours in this series was small, some of these tumours recurred several times, and this gave us the opportunity for a relatively long follow up in some of the cases. These longer follow up data revealed that, despite more than half of the grade 1 tumours first recurring with the same grade, the last recurrence in patients with initially low grade tumours exhibited the same differentiation in only one fifth of the cases. This favours the hypothesis that tumours progress in grade. These results contradict those of the Guy's Hospital series of 49 recurrent tumours, which were compared with their primaries, but that series included only one grade 1 tumour.16 Although the changes in grade of the first recurrence were minor compared with the grade of the baseline tumour, which closely matched the results in the Guy's Hospital study, the longer follow up period and the later recurrences pointed to a worsening of the histological grade. The higher number of grade 1 tumours in this present series might have contributed to the discrepancy between the results of the two series, despite the similarities in the methods. The Nottingham group has also investigated the consistency of the histological grade in breast carcinomas and their ovarian and axillary metastases.39 Although 20 of their 36 cases of advanced breast cancer, including one grade 1 breast carcinoma, retained their grade in the metastatic deposits, seven grade 2 and three grade 1 tumours became grade 3 in their metastases. Again, the numbers are low, but the fact that three of four grade 1 tumours turned to poorly differentiated carcinomas by the time of developing distant metastasis favours the hypothesis that histological grade may progress.

Although the question of tumour progression is far from being definitively answered and many controversial points remain, the present study appears to indicate that at least a proportion of low grade invasive breast carcinomas may progress to higher grade cancers during a long follow up period. If this is so, then high grade carcinomas therefore not only arise from high grade DCIS, but (at least in some cases) may also be a result of tumour progression from better differentiated invasive tumours. The incidence of this last phenomenon is unknown. It may be that grade 1 tumours capable of dedifferentiation are different from those that do not progress in grade; this would be consistent with the results of the comparative genomic hybridisation studies.17, 18

Acknowledgments

The data presented here are part of the background work of the “Investigation of tumour progression by means of comparative morphological assessment of primary tumours, metastases, and recurrences of recurrent breast carcinomas” OTKA T-037229 grant.

Abbreviations

DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ

LOH, loss of heterozygosity

REFERENCES

- 1.Fitzgibbons PL, Henson DE, Hutter RVP. Benign breast changes and the risk for subsequent breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998;122:1053–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mommers ECM, Poulin N, Sangulin J, et al. Nuclear cytometric changes in breast carcinogenesis. J Pathol 2001;193:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakhani SR. The transition from hyperplasia to invasive carcinoma of the breast. J Pathol 1999;187:272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diallo R, Schaefer K-L, Poremba C, et al. Monoclonality in normal epithelium and in hyperplastic and neoplastic lesions of the breast. J Pathol 2001;193:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher B. Laboratory and clinical research in breast cancer—a personal adventure. The David A. Karnovsky memorial lecture. Cancer Res 1980;40:3863–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halsted WS. The results of radical operations for the cure of cancer of the breast. Ann Surg 1907;46:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabár L, Fagerberg G, Day NE, et al. Breast cancer treatment and natural history: new insights from results of screening. Lancet 1992;339:412–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tubiana M, Koscielny S. The rationale for early diagnosis of cancer. The example of breast cancer. Acta Oncol 1999; 38:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cascinelli N, Greco M, Bufalino R, et al. Prognosis of breast cancer with axillary node metastases after surgical treatment only. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology 1987;23:795–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen PP, Groshen S, Saigo PE, et al. A long-term follow-up study of survival of stage I (T1M0) and stage II (T1N1) breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:355–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quiet CA, Ferguson DJ, Weichselbaum RR, et al. Natural history of node-positive breast cancer: the curability of small cancers with limited number of positive nodes. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:3105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellman S. Karnofsky memorial lecture. Natural history of small breast cancers. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:2229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tubiana M, Koscielny S. Natural history of human breast cancer: recent data and clinical implications. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1991;18:125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabár L, Fagerberg G, Chen HH, et al. Tumour development, histology and grade of breast cancers: prognosis and progression. Int J Cancer 1996; 66:413–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heimann R, Hellman S. Aging, progression, and phenotype in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millis RR, Barnes DM, Lampejo OT, et al. Tumour grade does not change between primary and recurrent mammary carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 1998;34:548–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roylance R, Gorman P, Harris W, et al. Comparative genomic hybridisation of breast tumors stratified by histological grade reveals new insights into the biological progression of breast cancer. Cancer Res 1999;59:1433–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buerger H, Otterbach F, Simon R, et al. Different genetic pathways in the evolution of invasive breast cancer are associated with distinct morphological subtypes. J Pathol 1999;189:521–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cserni G. Changing trends in lymph node recovery from axillary clearance specimens in breast cancer: possible implications for the quantitative axillary status from a 17 year retrospective study. Eur J Oncol 1997;2:403–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Joint Committee on Cancer. Breast. In: Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, et al, eds. AJCC cancer staging manual, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:171–80.

- 21.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology 1991;19:403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Assessment of histological grade. In: Elston CW, Ellis IO, eds. The Breast. Systemic pathology, 3rd ed, Vol. 13. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 1998:365–84.

- 23.Fleiss JL. The measurement of interrater agreement. In: Fleiss JL, ed. Statistical methods for rates and proportions, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1981:212–36.

- 24.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linell F, Ljungberg O. Carcinomas. In: Linell F, Ljungberg O, eds. Atlas of breast pathology. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1984:26–32.

- 26.Ellis IO, Galea M, Broughton N, et al. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. II. Histological type. Relationship with survival in a large study with long term follow-up. Histopathology 1992;20:479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinder SE, Elston CW, Ellis IO. Invasive carcinoma—usual histological types. In: Elston CW, Ellis IO, eds. The breast. Systemic pathology, 3rd ed, Vol. 13. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 1998:283–337.

- 28.Elston CW, Ellis IO, Goulding H, et al. The role of pathology in the prognosis and management of breast cancer. In: Elston CW, Ellis IO, eds. The breast. Systemic pathology, 3rd ed, Vol. 13. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 1998:385–433.

- 29.Lampejo OT, Barnes DM, Smith P, et al. Evaluation of infiltrating carcinomas with a DCIS component: correlation of the histologic type of the in situ component with the grade of the infiltrating component. Semin Diagn Pathol 1994;11:215–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas-Jones AG, Gupta SK, Attanoos RL, et al. A critical appraisal of six modern classifications of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast (DCIS): correlation with grade of associated invasive carcinoma. Histopathology 1996;29:397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diest PJ van. Ductal carcinoma in situ in breast carcinogenesis. J Pathol 1999;187:383–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buerger H, Mommers EC, Littmann R, et al. Correlation of morphologic and cytogenetic parameters of genetic instability with chromosomal alterations in in situ carcinomas of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol 2000; 114:854–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heimann R, Ferguson D, Recant WM, et al. Breast cancer metastatic phenotype as predicted by histologic tumor markers. Cancer J Sci Am 1997;3:224–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haybittle JL, Blamey R, Elston CW, et al. A prognostic index in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1982;45:361–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henson DE, Ries L, Freedman LS, et al. Relationship among stage of disease and histological grade for 22616 cases of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1991;22:207–19. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frierson HF, Wolber RA, Berean KW, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of the Nottingham modification of the Bloom and Richardson histological grading scheme for infiltrating ductal carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1995;105:195–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robbins P, Pinder S, deKlerk N, et al. Histological grading of breast carcinomas. A study of interobserver agreement. Hum Pathol 1995;26:873–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sleeman JP. The lymph node as a bridgehead in the metastatic dissemination of tumors. Recent Results Cancer Res 2000;157:55–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hitchcock A, Ellis IO, Robertson JFR, et al. An observation of DNA ploidy, histological grade, and immunoreactivity for tumour-related antigens in primary and metastatic breast carcinoma. J Pathol 1989;159:129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]