Abstract

The reported detection rate of prostate cancer, lesions suspicious for cancer, and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) in needle biopsies is highly variable. In part, technical factors, including the quality of the biopsies, the tissue processing, and histopathological reporting, may account for these differences. It has been thought that standardisation of tissue processing might reduce the observed variations in detection rate. Consensus among the members of the pathology committee of the European Randomised study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) concerning the optimal methodology of tissue embedding resulting in guidelines for prostatic needle biopsy processing was reached. The adoption of an unequivocal and uniform way of reporting lesions encountered in prostatic needle biopsies is considered helpful for decision taking by the clinician. The definition of parameters for quality control of prostatic needle biopsy diagnostics will further facilitate clinical epidemiological multicentre studies of prostate cancer.

Keywords: prostate cancer, needle biopsy, histopathology, tissue processing, quality control

Prostatic needle biopsies are an essential tool in the diagnosis of prostate cancer because they allow its definite diagnosis. Raised serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) concentrations prompt the clinician to perform transrectal or, less frequently, transperineal needle biopsies, which results into the discovery of many clinically non-manifest prostate cancers. A considerable downstaging and downgrading of prostate cancer has been achieved by this procedure.1,2 In the literature, much attention has been paid to the histological criteria of the most commonly accepted precursor lesion of prostate cancer—prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN)—and for “look a likes” of prostate cancer, such as postatrophic hyperplasia. In addition, much attention has been paid to the accuracy of prostate cancer grading in needle biopsies.3 Furthermore, small lesions resembling adenocarcinoma, which are occasionally encountered in prostatic needle biopsies and cause diagnostic difficulties, have been described.4

A few papers have looked at the quality of prostatic needle biopsy tissue processing.5,6 It was shown that an optimal processing procedure, leading to a maximum amount of tissue being examined by the pathologist, could increase the sensitivity for the detection of prostate cancer. These kinds of studies could provide a sound basis for a set of guidelines on the tissue processing of prostatic needle biopsies.

“Raised serum prostate specific antigen concentrations prompt the clinician to perform transrectal or, less frequently, transperineal needle biopsies, which results into the discovery of many clinically non-manifest prostate cancers”

The European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) is a collaboration of eight European centres that investigate the impact of screening for prostate cancer on mortality and quality of life of men between 50 and 75 years of age. These men are randomised into screening and non-screening arms.7 Screening consists of a systematic sextant needle biopsy procedure in men with raised PSA values. The pathology committee of the ERSPC was installed to obtain uniformity in histopathological reporting of the prostatic needle biopsy specimens and to enhance the quality of tissue processing. In a small side study within the ERSPC, it was noted that a substantial difference in the quality of prostatic needle biopsies was associated with discrepant detection rates among different participating centres of the ERSPC. Here, we report on the recommendations of the pathology committee of the ERSPC with regard to the processing and the reporting of prostatic needle biopsies.

UROLOGICAL WORK UP, REVIEW POLICY, AND ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES

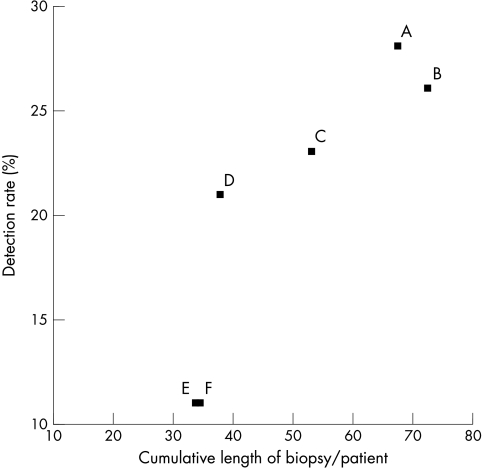

In a small side study, the slides of prostatic needle biopsies of 10 randomly selected participants of the ERSPC study from five centres were examined for their adequacy and their length. Needle biopsies were considered adequate if at least a single prostatic gland was present and needle biopsies that merely contained stromal tissue were considered inadequate. A considerable variation in the length of the biopsy sets was noted among different centres. The number of adequate needle biopsies for each case also differed. The average total amount of prostatic tissue for each participant and the detection rate of prostate cancer in the individual centres correlated well ( fig 1). It was noted that many biopsies were fragmented, which impeded a proper evaluation. In line with these data, Iczkowski et al demonstrated that the length of the biopsy correlates with the prostate cancer detection rate.8 Although these observations stress the importance of adequate tissue processing by the pathology laboratory, these data also show that the biopsy technique and the skill of the urologist can greatly influence the diagnostic outcome. Therefore, it is strongly recommended that the urological work up and the biopsy procedure should be performed by a limited number of experienced specialists in each screening centre.

Figure 1.

The relation between the cumulative length of sextant biopsies and the detection rate of prostate cancer in men who underwent sextant needle biopsy. Each letter in the figure represents a separate centre participating in the ERSPC

A learning curve may exist for pathologists who report prostatic needle biopsies. Therefore, it was initially agreed within the ERSPC that each ERSPC centre would institute a “reference” pathologist who is responsible for prostate needle biopsy diagnostics. Centres with a large, multistaff pathology laboratory have adopted the policy that the biopsies would be examined by the general pathologists, but that cases with malignancy, suspect lesions, or PIN would be reviewed by a reference pathologist. Data from one of the ERSPC centres revealed that after the review of approximately 1000 cancer cases, the diagnosis of prostate cancer was reversed by the reference pathologist in five cases. In two cases of a misdiagnosis of prostate cancer an exchange of material during the reporting had been made and in the remaining three cases postatrophic hyperplasia in needle biopsies had been mistaken for prostate cancer. In one additional case, where a prostate cancer was not found in the corresponding radical prostatectomy specimen, an exchange of one of the six biopsies between two different participants was eventually confirmed by molecular pathological analysis. Five of these six serious mistakes were avoided by the institution of the reference pathologist.

An obvious and simple measure to avoid mixing of biopsies by the pathologist is to deliver needle biopsies of one patient each on a separate plateau. For the cases of misdiagnoses by misinterpretation, it is likely that continued training of general pathologists by the reference pathologist and a low threshold consultation function of the reference pathologist can largely avoid false positive diagnoses.

GUIDELINES FOR ADEQUATE PROSTATIC TISSUE PROCESSING

The following processing issues have proved to be important for achieving a maximum amount of evaluable prostatic tissue in the prostatic needle biopsies.

The number of biopsies embedded in one cassette

Urologists want to know at which site the prostate cancer is located. This information may help to decide whether a unilateral nerve sparing prostatectomy is possible. In cases of lesions suspect for adenocarcinoma, it is important to know their localisation for site specific repeat biopsy. It is much preferable that each biopsy core should be embedded separately, but the consensus minimum requirement of the pathology committee of the ERSPC is that biopsies obtained from one side of the prostate should be embedded separately from those obtained from the other side. It is noted that separate embedding of each biopsy core was not explicitly recommended by the World Health Organisation pathology committee during the second international consultation9 or the Royal College of Pathologists UK.10 Obviously, if there are additional biopsies taken from a suspect lesion based on digital rectal examination or transrectal ultrasound they should always be embedded separately.

The procedure of embedding of needle biopsies into paraffin wax

Because needle biopsies tend to become curved after fixation, flat embedding of the biopsy cores can enhance the amount of tissue that is examined by the pathologist. Flattening of biopsy cores can be achieved by stretching the needle biopsies between two nylon meshes or by wrapping them in a piece of paper.6,11 This can be done even after initial formalin fixation. If multiple cores are embedded in one cassette, it is necessary to take care that all are separated from each other. This will prevent multiple entangled biopsies from being represented only partially in the mounted sections. An advantage of separate embedding of individual cores is that additional handling is avoided, reducing a source of damage to the biopsies.

Improvement for needle biopsy sectioning

Easy visualisation of the core biopsy in the paraffin wax greatly helps the cutting of sections without losing too much prostatic tissue. In some laboratories it is common practice to add eosin or another colour solution to the biopsies before embedding to allow easy visualisation for the histotechnician during sectioning of the paraffin wax block.

The number of sections from each biopsy core (levels of sectioning)

Earlier reports3,11,12 have shown that so as not to miss small foci of adenocarcinoma it is mandatory to cut several sections of each biopsy core at different levels. Cutting biopsy cores at different levels may allow a definite diagnosis of adenocarcinoma when a small focus is found at a single level. Because it was not reported whether biopsy cores were flattened before embedding the recommendation of these studies to cut three different levels may probably not be necessary in the case of adequately flattened cores. Therefore, within the pathology committee of the ERSPC it is recommended that subsequent sections of a core at two different levels should be sufficient. Ribbons between the two levels can be stored for cases where additional histological slides or immunohistochemistry are required.

Preservation of paraffin wax ribbons for additional staining

Some centres preserve paraffin wax ribbons of sectioned prostatic needle biopsies for the eventuality of additional stainings. Others perform two levels of sectioning in a way that saves approximately half of the tissue for additional sectioning if it is required. The use of a histo-collimator, a commercially available optical instrument for alignment of the block face to the cutting plane of the microtome, avoids tissue waste during recutting a previously sectioned paraffin wax block.

Most often, additional mounted sections will be requested if at the original levels a lesion suspect for adenocarcinoma is observed.

Immunohistochemistry and other stainings

In general, immunohistochemistry for basal cell specific keratin will be used to distinguish PIN, atrophy, or adenosis from adenocarcinoma.3 However, it should be stressed that the absence of basal cell staining may not be considered to be definite proof of malignancy.13 Some centres consider it helpful to perform mucin stainings14 or Van Gieson stainings on suspect lesions to establish a definite diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

GUIDELINES FOR UNIFORM REPORTING OF PROSTATE LESIONS

In screened populations we generally deal with men without manifest prostate cancer. These men frequently lack signs of prostate cancer at digital rectal examination or transrectal ultrasonography. Increased PSA values, digital rectal examinations, or transurethral ultrasonography lack specificity for the detection of prostate cancer. A well known example of a false positive outcome of clinical examination is granulomatous prostatitis leading both to a suspect lesion at digital rectal examination and very high concentrations of PSA.15 To avoid bias, we and others3 recommend that pathologists read the needle biopsies blindly; that is, without knowledge of the outcome of previous clinical examinations.

Reporting of the histopathology of prostatic needle biopsies in a screening setting should be as unequivocal and concise as possible. This means that the nomenclature of prostatic lesions in pathology reports should be uniform.10 Terms such as “atypical glands”, “glandular atypia”, “probably malignant”, “but benign not excluded” should be avoided, because it is not clear to the urologist what further action should be taken. The nomenclature of lesions that are “suspicious but not diagnostic for prostate cancer” has been much debated.4,16,17

“Reporting of the histopathology of prostatic needle biopsies in a screening setting should be as unequivocal and concise as possible”

The number of biopsies and the length of each needle biopsy should be given in the gross description (macroscopy) section of the pathology report.10 Inadequacy of any prostatic needle biopsies should be stated in the pathology report. An inadequate prostatic core biopsy is defined as a core lacking glandular structures. For review in cases of a later occurring carcinoma, it is important to know to what extent the original sextant core biopsies were diagnostically adequate. Particularly when one or more separate core biopsies are taken from an area clinically suspect for malignancy, it is of importance to mention this inadequacy in the report. If seminal vesicle tissue is present in any of the biopsies this should be stated in the report.

The following terms are recommended by the pathology committee of the ERSPC because they seem to have proved their value and consistency in the past several years.

Benign, no abnormality. This includes fibromuscular and glandular hyperplasia, in addition to foci of chronic (lymphocytic) inflammation. It has been noted that distinctions between the above entities are of limited clinical relevance and subject to considerable interobserver variation.18

Acute inflammation, characterised by damage to glandular structures by inflammatory cells or the presence of leucocytes in the glandular lumina. The extent of acute inflammation (for example, the number of biopsies involved) may also be indicated because this information may explain increased serum PSA values or clinical findings.

Chronic granulomatous inflammation, which includes xanthogranulomatous inflammation. This condition can cause greatly raised PSA concentrations and a false positive digital rectal examination.15

(Extensive) atrophy, no malignancy. In particular, multiple biopsies with postatrophic hyperplasia may be reported as such, although in itself this finding has no clinical consequence.

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). Although initially low and high grade PIN were distinguished, now only (high grade) PIN is reported. The histological criteria required for a diagnosis of (high grade) PIN are described by Bostwick.9,19 The single most important criterion is the presence of prominent nucleoli in at least 10% of the dysplastic luminal cells. The extent and architectural pattern of PIN may also be reported because some types (solid, comedo, and cribriform) may be associated with prostate cancer because they may represent intraductal spread of high grade cancer.20

Adenocarcinoma. The location(s) of the foci of adenocarcinoma should be recorded. In this way, the number of positive biopsies is implicitly known to the clinician. If a small focus (< 3 mm) of adenocarcinoma is present in only one needle biopsy this may be recorded as “focal adenocarcinoma” in the conclusion, although the clinical relevance of this term might be limited.3,21 The pathology committee of the ERSPC recommends an estimation of the proportion of tumour involvement of the needle biopsies, particularly for study reasons.22,23 Extensive involvement may discourage surgical treatment.24 It is common practice to report the presence of perineural invasion of the adenocarcinoma, although its clinical impact is controversial.18,23,24

Suspect for but not diagnostic for adenocarcinoma, if the lesion is too small and/or lacks sufficient criteria to be able to make a definite diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.18 No difference is made between lesions that are probably benign and those that are probably malignant because this will not change the follow up policy.25 The pathology committee of the ERSPC recommends none of the acronyms that have been proposed recently, such as AAP (atypical acinar proliferation) or ASAP (atypical small acinar proliferation). First, lesions suspicious for adenocarcinoma do not represent a separate entity and second, their morphology may vary from a few single atypical cells to strands of abnormal cells or glands with atypical features. This diagnosis is followed by repeat biopsies directed at the site of the initial lesion.

Other malignancies, including carcinosarcoma, sarcoma, adenocarcinoma of the colon, etc.

When adenocarcinoma, high grade PIN, or lesions suspect for adenocarcinoma are present at separate sites, they should also be reported separately. Table 1 lists the potential clinical consequences of the most common diagnoses.

Table 1.

Prostatic needle biopsy diagnosis and clinical relevance in early detection programme (The Rotterdam algorithm22)

| Diagnosis | Consequence |

| Inadequate material | Repeat sextant biopsies within 1 year |

| Benign | Rescreening at the regular intervals |

| Inflammation, either acute or granulomatous | Rescreening at the regular intervals |

| Isolated high grade PIN, no cancer, no lesion suspect for cancer | Repeat sextant needle biopsies within 6 months |

| Lesion suspect for cancer, no definite cancer | Additional biopsies from region suspected of carcinoma within 6 weeks |

| Definite adenocarcinoma | Referal to clinician/treatment |

| Other malignancy | Referal to clinician/treatment |

PIN, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia.

Diagnostic pitfalls3 include:

Adenosis, which fortunately is a very rare finding in peripheral zone derived needle biopsies. Adenosis, which is characterised by a condensation of small glands surrounded by sporadic basal cells, is also known as atypical adenomatous hyperplasia.26 This last term is not recommended by all members because “atypical” may suggest a relation with malignancy.

Postatrophic lobular hyperplasia (frequent).

Seminal vesicle (frequent).

Glands of the verumontanum (frequent).

Nephrogenic adenoma or nephrogenic metaplasia (very rare).

Sclerosing adenosis (very rare).

GUIDELINES FOR REPORTING OF PROSTATE CANCER GRADE

Although several grading systems can be used, it is recommended that the Gleason score system should be used. Advantages of this grading system are its general use and the large amount of data in the literature on its prognostic impact and accuracy. Furthermore, the Gleason score system is based on architectural features, which are easy to learn (see website www.pathology.ks.se/egevad/engGleason.html or http://www.eur.nl/fgg/pathol/quiz.htm for self-assessment on needle biopsies). The participation of pathologists in external quality assurance programmes for prostate cancer grading (if available) is recommended to reduce interobserver variation.

As advocated by Epstein,27 Gleason scores of 2 to 4 should not be attributed to prostatic adenocarcinoma on needle biopsies. We would recommend that the lowest Gleason growth pattern that can be assessed in needle biopsies is growth pattern 3, implying that a Gleason score of 6 is the lowest possible on peripheral zone needle biopsies.

“The pathology committee of the ERSPC recommends none of the acronyms that have been proposed recently, such as AAP (atypical acinar proliferation) or ASAP (atypical small acinar proliferation)”

An important feature of the Gleason system is that it takes into account the heterogeneity of prostate cancer by including the two most prominent growth patterns. Thus, in sextant needle biopsies the Gleason score can range from 6 to 10. The location of a separate area of high grade (Gleason growth pattern 4 or 5) should always be reported, irrespective of its extent in the needle biopsy. If, in addition to the predominant growth pattern 3, both pattern 4 and 5 are present in the needle biopsies it is suggested that the highest pattern in addition to the predominant pattern should be included in the Gleason score (that is, 3 + 5 = 8). This follows the guidelines of the American College of Pathologists.28

QUALITY CONTROL

The standardisation of processing and reporting on prostate needle biopsies to avoid medicolegal complications will become increasingly important. It is recommended that pathologists responsible for reporting on prostatic needle biopsies participate in an external quality assurance programme to reduce interobserver variation in diagnosis and Gleason score grading.

As a measure of quality control, the average length of needle biopsies and the percentage of inadequate biopsies can be used. The frequency of suspect lesions should give an indication as to the degree of confidence reached by the pathologist. This is of course related to several factors, including the population under study, the quality of needle biopsies and their processing, in addition to the staining and the confidence of the pathologist. For instance, in the setting of prostate cancer screening, the percentage of suspect lesions should not rise above 5% because this will lead to a too frequent indication of repeat biopsies.

Take home messages

The urological work up and the biopsy procedure should be performed by a limited number of experienced specialists in each screening centre and in each centre an experienced “reference pathologist” should review suspicious cases

With regard to tissue processing, ideally each biopsy core should be embedded separately (at minimum, biopsies from either side of the prostate should be embedded separately), biopsies should be flat embedded and sections of the core should be taken at two levels

The nomenclature of prostatic lesions in pathology reports should be uniform and the following terms are recommended: benign, no abnormality; acute inflammation; chronic granulomatous inflammation, atrophy, no malignancy; prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (with the extent and architectural pattern being reported); adenocarcinoma (with the locations of the foci being recorded); suspect for but not diagnostic for adenocarcinoma; and other malignancies

The Gleason score system should be used because of its general use and its prognostic power

As a measure of quality control, the average length of needle biopsies and the percentage of inadequate biopsies can be used

Abbreviations

ERSPC, European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer

PIN, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

PSA, prostate specific antigen

REFERENCES

- 1.Mettlin C, Murphy GP, Babaian RJ, et al. The results of a five-year early prostate cancer detection intervention. Investigators of the American Cancer Society national prostate cancer detection project. Cancer 1996;77:150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoedemaeker RF, Rietbergen JB, Kranse R, et al. Histopathological prostate cancer characteristics at radical prostatectomy after population based screening. J Urol 2000;164:411–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein JI. The diagnosis and reporting of adenocarcinoma of the prostate in core needle biopsy specimens. Cancer 1996;78:350–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iczkowski KA, Bassler TJ, Schwob VS, et al. Diagnosis of “suspicious for malignancy” in prostate biopsies: predictive value for cancer. Urology 1998;51:749–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane RB, Jr, Lane CG, Mangold KA, et al. Needle biopsies of the prostate: what constitutes adequate histologic sampling? Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998;122:833–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogatsch H, Mairinger T, Horninger W, et al. Optimized preembedding method improves the histologic yield of prostatic core needle biopsies. Prostate 2000;42:124–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroder FH, Kranse R, Rietbergen J, et al, members of the ERSPC, Section Rotterdam. The European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC): an update. Eur Urol 1999;35:539–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iczkowski KA, Casella G, Seppala RJ, et al. Needle core length in sextant biopsies influences prostate cancer detection rate. Urology 2002;59:698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bostwick DG, Foster CS, Algaba F, et al. Prostate tissue factors. In: Murphy G, Denis L, Khoury S, et al, eds. Prostate cancer. Second International Consultation on Prostate Cancer. Co-sponsored by WHO and UICC, June 27–29, Paris: Plymbridge Distributors, 1999.

- 10.The Royal College of Pathologists. Standards and minimum datasets for reporting cancer. Minimum dataset for prostate cancer histopathology reports. London: The Royal College of Pathologists, 2000.

- 11.Humphrey PA, Walther PJ. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate I. Tissue sampling considerations. Am J Clin Pathol 1993;99:746–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyes AO, Humphrey PA. Diagnostic effect of complete histologic sampling of prostate needle biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol 1998;109:416–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein NS, Underhill J, Roszka J, et al. Cytokeratin 34 beta E-12 immunoreactivity in benign prostatic acini. Quantitation, pattern assessment, and electron microscopic study. Am J Clin Pathol 1999;112:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iczkowski KA, Bostwick DG. Criteria for biopsy diagnosis of minimal volume prostatic adenocarcinoma: analytic comparison with nondiagnostic but suspicious atypical small acinar proliferation. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppenheimer JR, Kahane H, Epstein JI. Granulomatous prostatitis on needle biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1997;121:724–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein JI. How should atypical prostate needle biopsies be reported? Controversies regarding the term “ASAP”. Hum Pathol 1999;30:1401–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iczkowski KA, Cheng L, Qian J, et al. ASAP is a valid diagnosis. Atypical small acinar proliferation. Hum Pathol 1999;30:1403–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein JI, Potter SR. The pathological interpretation and significance of prostate needle biopsy findings: implications and current controversies. J Urol 2001;166:402–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bostwick DG. Prospective origins of prostate carcinoma. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia. Cancer 1996;78:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen RJ, McNeal JE, Baillie T. Patterns of differentiation and proliferation in intraductal carcinoma of the prostate: significance for cancer progression. Prostate 2000;43:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noguchi M, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, et al. Relationship between systematic biopsies and histological features of 222 radical prostatectomy specimens: lack of prediction of tumor significance for men with nonpalpable prostate cancer. J Urol 2001;166:104–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoedemaeker RF, van der Kwast TH, Boer R, et al. Pathologic features of prostate cancer found at population-based screening with a four-year interval. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:1153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin MA, Bassily N, Sanda M, et al. Relationship and significance of greatest percentage of tumor and perineural invasion on needle biopsy in prostatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De la Taille A, Rubin MA, Bagiella E, et al. Can perineural invasion on prostate needle biopsy predict prostate specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy? J Urol 1999;162:103–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iczkowski KA, Bassler TJ, Schwob VS, et al. Diagnosis of “suspicious for malignancy” in prostate biopsies: predictive value for cancer. Urology 1998;51:749–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bostwick DG, Srigley J, Grignon D, et al. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the prostate: morphologic criteria for its distinction from well-differentiated carcinoma. Hum Pathol 1993;24:819–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein JI. Gleason score 2–4 adenocarcinoma of the prostate on needle biopsy: a diagnosis that should not be made. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:477–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srigley JR, Amin MB, Bostwick DG, et al, for members of the Cancer Committee, College of American Pathologists. Updated protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with carcinomas of the prostatic gland. A basis for checklists. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:1034–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]