Abstract

Aims: Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology is an accepted means of diagnosing and typing common forms of lymphoma, particularly small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and large B cell lymphoma. However, its usefulness for diagnosing less common forms of lymphoma is not clearly established and this study was designed to examine this.

Methods: The study reviewed the FNAs of suspected lymphomas collected over a period of approximately five years.

Results: FNA samples were available for 138 definite lymphomas; most were common forms of B cell lymphoma. However, there was also one Burkitt lymphoma (BL), two Burkitt-like large B cell lymphomas, 15 classic Hodgkin lymphomas (HLs), two nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphomas, four mantle cell lymphomas, two mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphomas (MLBCLs), 11 peripheral T cell lymphomas (PTCLs), and five T cell rich large B cell lymphomas (TCRLBCLs).

Conclusions: FNA diagnosis of BL was possible with immunoflow cytometry (IFC), cell block immunohistochemistry (IHC), and cell block fluorescent in situ hybridisation for c-myc alteration. It was difficult to make a definite diagnosis of HL and MLBCL on FNA alone. Both tend to be sclerotic tumours and FNA tends to yield scanty neoplastic cells. The FNA diagnosis of PTCL depended on cell block IHC; IFC was not usually useful. TCRLBCL did not show light chain restriction on IFC of FNA samples, probably because of frequent reactive B cells in the tumour. Thus, HL, MLBCL, and TCRLBCL are often difficult to diagnose accurately on FNA cytology, even when using IFC and cell block IHC.

Keywords: fine needle aspiration cytology, cytology, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, lymphoma

In the past 10 years, fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology has become accepted as a means of diagnosing and typing common forms of lymphoma, particularly small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and large B cell lymphoma.1–8 These types of lymphoma alone make up approximately 70% of all lymphomas. The usefulness of FNA cytology in the diagnosis of these lymphomas is reliant on immunoflow cytometry (IFC) and cell block immunohistochemistry (IHC). It is also reliant on the pathologist making “near patient” provisional assessment of the nature of the specimen and then collecting appropriate specimens.

However, the usefulness of FNA cytology in the diagnosis of less common forms of lymphoma is not clearly established, and our study set out to examine this issue.

METHODS

The method was similar to that described in a previous study from our department.6 The study was set in a large tertiary referral hospital in rural New Zealand. We reviewed the FNAs of suspected lymphomas collected over a period of approximately five years. Most of these were either benign or were common forms of lymphoma that were not the focus of our present study. The cases selected for further examination were those with a final diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma, Burkitt-like large B cell lymphoma, classic Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma, peripheral T cell lymphoma, and T cell rich large B cell lymphoma.

The FNAs were performed by one of three pathologists with an interest in FNA cytology, except for image guided FNAs, in which the needle was given to one of these pathologists for preparation of the slides after the radiologist had aspirated the lesion. Early on in the study, the pathologist frequently visited the patients on the wards to perform FNAs, but this was often unsatisfactory because the patient was unavailable or distracted. Later in the study, the patients were brought to the outpatients’ clinic in the pathology department. The FNAs performed by the pathologists were done with a needle only technique, using a 23 or 25 gauge 1.5 inch (38 mm) needle. The slides were air dried, often aided by a small hair dryer, and Diff-Quik® stained (Dade Behring Diagnostics, Newmarket, Auckland, New Zealand). The slides were then examined with a portable Olympus CHK microscope and a hand written report was issued within a few minutes. If this examination of the specimen suggested that the lesion might be lymphoid and lymphoma seemed possible, then a second FNA was performed, still using a needle only technique, to collect a second sample. This sample was collected quickly and the needle was washed through with 3 ml of heparin RPMI (12.8 mg of heparin ammonium in 45 ml of RPMI) within a few seconds of being collected. The slides were taken back to the laboratory to be mounted and examined again. The specimen in heparin RPMI was taken to the haematology laboratory, transferred to a 5 ml tube, and centrifuged for two minutes at approximately 400 ×g. The supernatant was discarded and the cells were resuspended in 2 ml of ammonium chloride lysis solution. The cells were gently vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes, and then centrifuged again for two minutes. The leucocytes were then resuspended in 2 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). If debris was present, it was removed with a nylon Swiss screen filter. An approximate cell count was performed and a panel of directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies was selected (Immunotech, Westbrook, Maine, USA). The cells and the antibodies were incubated for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature, after which they were washed once in PBS, centrifuged, and washed again. They were then analysed with the flow cytometer. Material for κ and λ light chain analysis was treated differently. The centrifuged sample in heparin RPMI was incubated with prewarmed PBS for 20–30 minutes at 37°C, to remove cytophilic immunoglobulin, and then centrifuged. The supernatant was discarded and if red cells were present then they were lysed with ammonium chloride as above. Cells were then incubated with antibodies (CD19 and anti-κ or CD19 and anti-λ) as above.

The “first run” panel of antibodies evolved as our experience developed and with the acquisition of a new immunoflow cytometer approximately a quarter of the way through our study. In some cases we performed a “second run” with a more specialised panel to investigate a specific diagnosis. The number of antibodies used was sometimes restricted by the scarcity of cells. At the start of our study, a Coulter PROFILE II was used, but later the laboratory obtained a Coulter EPICS® XL (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California, USA).

In our laboratory we have adopted light chain ratio limits from previous studies.4–6 A κ to λ ratio of greater than 3 or a λ to κ ratio of greater than 2 were accepted as evidence of monoclonality.

For some cases, cell blocks for immunohistochemistry were collected as in our earlier paper.9 These were usually taken after the initial FNA showed overtly malignant cytology, as described previously.6 Recently we have adopted a variation of this method when possible. This involves placing the drop of sample on the upturned lid of the specimen container instead of washing it into the formalin. The lid is left upturned for a few minutes to allow the sample to start to clot. The lid is then turned over and screwed down. The drop of sample on the lid is then left to fix in the formalin vapour for a least six hours. It is then prised off the lid with a scalpel blade and is treated as if it were a routine biopsy histology specimen. This “clot block” gives rise to a higher density of cellular material than is obtained from a cell block formed from agar, shows fewer artefacts, and requires less preparation.

Cell block fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) was performed on cell blocks from three cases of possible Burkitt lymphoma to examine possible c-myc gene rearrangements. The sections for FISH were prepared in the same way as for cell block immunohistochemistry. They were then tested with an 8q24 c-myc break gene rearrangement probe.

RESULTS

During our five year study period, a total of 138 definite lymphomas were diagnosed that had FNA samples available. Most of these 138 tumours were common forms of B cell lymphoma. However, there was also one case of Burkitt lymphoma, two of Burkitt-like large B cell lymphoma, 15 of classic Hodgkin lymphoma, two of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, four of mantle cell lymphoma, two of mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma, 11 of peripheral T cell lymphoma, and five of T cell rich large B cell lymphoma. Table 1 shows the details of these cases. The first three cases in table 1 were suspected Burkitt lymphomas and had cell block FISH performed, but this demonstrated an abnormality only in case 2.

Table 1.

Details of the uncommon forms of B cell lymphoma encountered in our study

| Case | Site | Method | Initial diagnosis | Percentage of cells positive (numbers indicate CD numbers) | Cell block | Biopsy | Final diagnosis | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 19 | 20 | 23 | IgM | FMC77 | 77 | 19+κ | 19+λ | 5+19 | 4+8 | |||||||

| 1 | Para-aortic | I | Large cell lymphoma | 17 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 79 | 91 | 79 | 3 | 2 | 73 | 94 | 86 | 6 | 0 | 1 | Yes | No | BLBCL | |

| 2 | Mesenteric | I | Lymphoma | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 2 | 24 | 99 | 44 | 99 | 10 | 0 | 0 | Yes | No | BL; partially necrotic | |

| 3 | Right neck | M | Lymphoma | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 96 | 90 | 98 | 3 | 98 | 96 | 42 | 95 | 8 | 8 | 0 | No | Yes | BLBCL |

| 4 | Left axilla | M | ?HL | 30 | 23 | 99 | 6 | 0 | 68 | 71 | 54 | 71 | 28 | 65 | 1 | 67 | 0 | No | Yes | HL and CLL (on biopsy) | ||

| 5 | Left supraclavicular | M | Reactive | Inadequate for flow cytometry | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||||||||

| 6 | Left neck | M | Reactive | Inadequate for flow cytometry | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||||||||

| 7 | Left neck | M | ?Lymphoma | Inadequate for flow cytometry | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | Mediastinum | I | Reactive | 90 | 77 | 87 | 20 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 23 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 3 | <1 | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | ||

| 9 | Left neck | M | Reactive | 69 | 31 | 15 | 20 | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Left inguinal | M | ?HL | 90 | 81 | 93 | 14 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 5 | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | ||

| 11 | Left neck | M | Inadequate cells | Inadequate for flow cytometry | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | Mediastinal | I | ?Lymphoma | 90 | 77 | 20 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||

| 13 | Mediastinal | I | ?Lymphoma | Inadequate for flow cytometry | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||||||||

| 14 | Mediastinal | I | ?Lymphoma | Inadequate for flow cytometry | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||||||||

| 15 | Left cervical | M | ?HL | 28 | 51 | 8 | 1 | 49 | 47 | 4 | 48 | 34 | 23 | 4 | 0 | Yes | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | ||||

| 16 | Left neck | M | ?HL | Inadequate for flow cytometry | Yes | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||||||||

| 17 | Left inguinal | M | ?Lymphoma | 95 | 95 | 18 | 92 | 80 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | No | Yes | HL (on biopsy histology) | |

| 18 | Right axilla | M | ?HL | 82 | 96 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | No | No | HL (on cytology only) | |||||||

| 19 | Left neck | M | Reactive | 88 | 88 | 71 | 87 | 18 | 2 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 31 | 12 | 19 | 16 | 2 | 2 | No | Yes | NLPHL (on biopsy histology) | |

| 20 | Mesenteric | I | ?HL | 99 | 91 | 88 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | No | Yes | NLPHL (on biopsy histology) | ||||||

| 21 | Left submental | M | Lymphoma | 6 | 6 | 3 | 99 | 3 | 1 | 93 | 90 | 4 | 93 | 90 | 4 | 93 | 93 | 0 | No | Yes | MCL (on biopsy histology) | |

| 22 | Right neck | M | Lymphoma | 6 | 11 | 2 | 92 | 5 | 2 | 87 | 95 | 5 | 94 | 59 | 89 | 2 | 80 | 0 | No | Yes | MCL (on biopsy histology) | |

| 23 | Right breast | M | Lymphoma | 2 | 5 | 5 | 100 | 6 | 1 | 99 | 99 | 14 | 99 | 99 | 2 | 97 | 99 | Yes | No | MCL (recurrent) | ||

| 24 | Left parotid | M | Lymphoma | 4 | 2 | 100 | 1 | 1 | 97 | 99 | 12 | 98 | 5 | 95 | 97 | 1 | No | Yes | MCL (on biopsy histology) | |||

| 25 | Mediastinal | I | ?Lymphoma | Inadequate for flow cytometry or cell block | No | Yes | MLBCL | |||||||||||||||

| 26 | Mediastinal | I | ?Lymphoma | Inadequate for flow cytometry or cell block | No | Yes | MLBCL | |||||||||||||||

| 27 | Perihepatic mass | I | Lymphoma/carcinoma | 80 | 62 | 78 | 10 | <1 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 5 | <1 | <1 | Yes | Yes | PTCL (on biopsy histology) | |||||

| 28 | Left neck | M | Malignant | 76 | 42 | 78 | 31 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | No | Yes | PTCL (on biopsy histology) | |||

| 29 | Left cervical | M | Lymphoma | 68 | 63 | 49 | 60 | 11 | 0 | 18 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 0 | No | Yes | PTCL (on biopsy histology) ALK-1+ | |

| 30 | Right neck | M | Malignant | 93 | 43 | 83 | 41 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6 | No | Yes | PTCL (on biopsy histology) Lennert’s | ||||||||

| 31 | Right neck | M | Lymphoma | 94 | 78 | 89 | 1 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 84 | Yes | No | PTCL (on cell block histology) | |||||

| 32 | Left neck | M | Malignant | 70 | 0 | 16 | 10 | 13 | Yes | No | PTCL (on cell block histology) | |||||||||||

| 33 | Right calf | M | Lymphoma | 98 | 5 | 96 | 95 | 11 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 | Yes | No | PTCL (on cell block histology) | |||||

| 34 | Left neck | M | Malignant | 68 | 17 | 51 | 60 | 40 | <1 | 7 | 37 | No | Yes | PTCL (on cell block histology) | ||||||||

| 35 | Left inguinal | M | Lymphoma/carcinoma | 70 | 42 | 26 | 3 | 30 | 30 | 5 | 5 | Yes | Yes | PTCL (on cell block histology) | ||||||||

| 36 | Left inguinal | M | Lymphoma | 85 | 61 | 83 | 24 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 9 | <1 | 6 | 6 | <1 | <1 | Yes | No | PTCL (on cell block histology) | |||

| 37 | Left leg | M | Lymphoma | 100 | 7 | 91 | 60 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 10 | 21 | 13 | No | Yes | PTCL (recurrent) | ||||||

| 38 | Right inguinal | M | Lymphoma/carcinoma | 94 | 58 | 86 | 22 | 1 | 14 | 13 | 5 | 17 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 | Yes | Yes | TCRBCL (on biopsy histology) | ||

| 39 | Left neck | M | Probable carcinoma | 98 | 41 | 90 | 48 | 1 | 17 | 12 | Yes | Yes | TCRBCL (on biopsy histology) | |||||||||

| 40 | Left neck | M | ?Lymphoma | 87 | 9 | 6 | 6 | No | Yes | TCRBCL (on biopsy histology) | ||||||||||||

| 41 | Right neck | M | ?Lymphoma | 89 | 75 | 48 | 83 | 26 | 27 | 14 | 11 | 5 | 25 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | No | Yes | TCRBCL (on biopsy histology) | |

| 42 | Left neck | M | ?Lymphoma | 79 | 55 | 76 | 18 | 6 | 28 | 30 | 6 | 30 | 35 | 26 | 20 | 8 | 0 | No | Yes | TCRBCL (on biopsy histology) | ||

BL, Burkitt lymphoma; BLBCL, Burkitt-like large B cell lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; FNA, fine needle aspiration; I, image guided FNA; M, manually guided FNA; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MLBCL, mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma; NLPHL, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; PTCL, peripheral T cell lymphoma; TCRBCL, T cell rich B cell lymphoma.

DISCUSSION

The case of Burkitt lymphoma and the two cases of Burkitt-like large B cell lymphoma were similar in that they all had morphology consistent with Burkitt lymphoma and strongly expressed CD10 and CD77 on IFC. Only in case 2 did cell block FISH show a 8q24 c-myc breakpoint gene rearrangement to confirm the diagnosis. The use of cell block FISH instead of conventional cytogenetics has the advantage that the cytogenetics can be performed as an afterthought. In practice, it is rarely necessary to obtain cytogenetic information to type common forms of lymphoma, so that the use of the limited amount of sample material in this way is not warranted. Cytogenetics becomes an expensive investigation if done unselectively.

Of the 15 cases of classic Hodgkin lymphoma only one yielded inadequate cells for cytological examination. It was thought that five were probably Hodgkin lymphoma.

“The use of cell block fluorescent in situ hybridisation instead of conventional cytogenetics has the advantage that the cytogenetics can be performed as an afterthought”

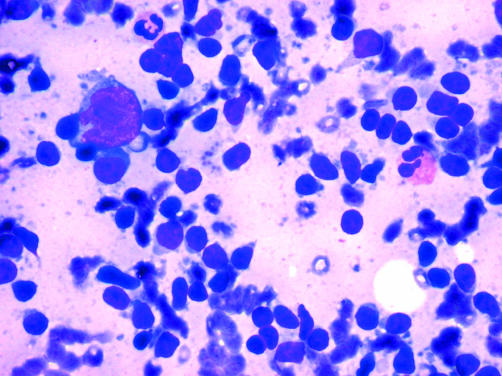

Five were considered to be “possible lymphoma”. Five were considered to be reactive on cytology and even on review did not show convincing Reed-Sternberg cells (fig 1). Seven yielded insufficient cells for IFC. All of the cases for which IFC was performed showed a predominant population of T cells, except for case 4. This patient had had chronic lymphocytic leukaemia for many years and had then developed synchronous classic Hodgkin lymphoma. A predominant population of T cells was also found in the two cases of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Of these two cases, one was thought to be reactive on FNA cytology and it was thought that the other was probably Hodgkin lymphoma. The potential of Hodgkin lymphoma to yield misleading “reactive” FNA cytology diagnoses has been discussed in previous papers, as has the difficulty in obtaining sufficient cells from these cases for IFC. In a recent study Chhieng et al reviewed FNAs of 89 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma.10 Based on a comparison of the histological diagnosis and original cytological diagnosis, 43 cases had a positive diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma, 20 had a suspicious or atypical diagnosis, 13 had a benign diagnosis (false negative cases), and 10 were non-diagnostic. Three additional cases had a malignant diagnosis other than Hodgkin lymphoma. Chhieng et al appear to have made definite diagnoses of Hodgkin lymphoma on FNA cytology. In our laboratory, we would not usually make a definite diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma without a biopsy, particularly since the recognition of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma as a separate entity to classic Hodgkin lymphoma. This also appears to be the view of Young and Al-Saleem.7 An exception would be in the event of recurrent disease that had been previously biopsy confirmed. Another exception would be if the patient’s clinical condition was so poor that a biopsy was not possible before treatment. The only case of Hodgkin lymphoma in our study that did not have a biopsy was a patient with Ann Arbor stage IV disease. Chemotherapy was initiated immediately after the FNA. Cell block IHC can assist in the diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma and the distinction between classic Hodgkin lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. However, in practice, it is often not possible to obtain a sufficiently cellular sample for a cell block. The reason for this is probably that classic Hodgkin lymphoma is usually a sclerotic tumour, and also the neoplastic cells are only a minor component of the (usually) scanty sample.

Figure 1.

A Diff-Quik® stained fine needle aspiration of a classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Typically, Reed-Sternberg cells are either absent or are only scanty, and even then typical bilobate nuclear morphology is often not seen clearly.

Take home messages.

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma was possible with immunoflow cytometry (IFC), cell block immunohistochemistry (IHC), and fluorescence in situ hybridisation for c-myc alteration

The definite diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma and mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma was difficult on FNA alone

The FNA diagnosis of peripheral T cell lymphoma depended on cell block IHC, and IFC was not useful

T cell rich large B cell lymphomas did not show light chain restriction on IFC of FNA samples, probably because of frequent reactive B cells in the tumour

Thus, although FNA is accurate for diagnosing and typing common forms of lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma, and T cell rich large B cell lymphoma are often difficult to diagnose accurately on FNA cytology, even with the use of IFC and cell block IHC

A “small cell” lymphoma with an immunophenotype of CD5+, CD19+, and CD23− strongly suggests a mantle cell lymphoma. Typically, mantle cell lymphoma has rather characteristic nuclear features, including monotonous nuclei with finely stippled chromatin.7,8 However, there are variants with an atypical appearance and immunophenotype.11 To make a definite diagnosis one usually needs to demonstrate nuclear overexpression of cyclin D1 on immunohistochemistry. Consequently a biopsy was performed for three of the four cases. The remaining case was recurrent mantle cell lymphoma, and cyclin D1 overexpression was demonstrated on cell block immunohistochemistry.

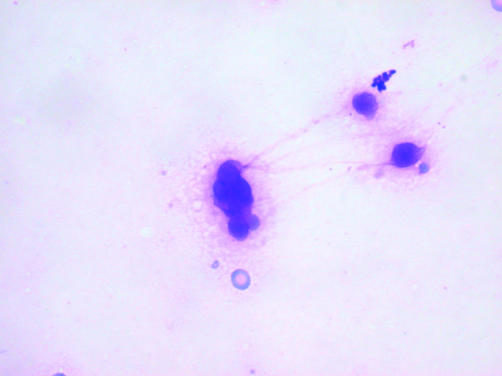

There were only two cases of mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma. Both had a classic presentation of superior vena caval obstruction in a young woman, which forewarned the pathologist of the probable diagnosis. Both cases showed extremely scanty cellularity on image guided FNA. In one patient, it was necessary to repeat the aspiration five times before the pathologist could be confident that he could identify malignant cells. There were less than a total of 50 tumour cells obtained from the five attempts, and many of these showed pronounced artefacts (fig 2). A core biopsy was taken from both patients to confirm the cytological diagnosis, although treatment was initiated on the cytology results because of the urgency arising from the superior vena caval obstruction.

Figure 2.

A Diff-Quik® stained fine needle aspiration of a mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma. This type of lymphoma yielded very scanty cells that often exhibited artefacts and were difficult to interpret. In one patient, five aspirations were required before a definite diagnosis of malignancy could be made.

There were 11 peripheral T cell lymphomas. Two of these showed loss of pan-T antigens, CD5 (case 31) and CD3 (case 34). These cases also showed coexpression of CD4 and CD8. A definite FNA diagnosis of peripheral T cell lymphoma was possible for six patients using cell block IHC. The others required biopsy, except patient 37 in whom the tumour was recurrent and the diagnosis was made on cytology alone. In contrast, a previous study of the FNA diagnosis of 20 T cell lymphomas by Al Shanqeety and Mourad found abnormal T cell antigen expression in 17 cases. Loss of CD7 was found in half of the cases.12 Another study by Yao et al showed abnormal T antigen expression in 13 of 21 cases of peripheral T cell lymphoma.13 If a greater variety of T cell IFC markers had been used in our laboratory, including CD7, then we might have found abnormal expression in more of the peripheral T cell lymphomas. However, peripheral T cell lymphomas are obviously malignant on cytology alone. Faced with this, cell block IHC for CD20 and CD3 is a more straightforward strategy for finalising the diagnosis than using a scanty sample for IFC with an extended panel of markers in the anticipation that abnormal expression might be found.

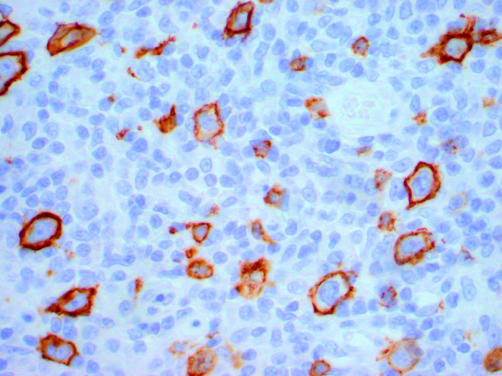

There were five cases of T cell rich large B cell lymphomas. All of these showed no evidence of light chain restriction. An examination of the IFC results for these cases shows that the proportion of B cells in these cases (CD19 or CD20 positive) ranged from 1% to 30%. However, on examining the CD20 immunostain on the corresponding histological material it is evident that many of the CD20 positive cells were in fact small benign B cells. Although relatively inconspicuous because of their small size, these benign B cells are often numerous (fig 3). A simple calculation shows that it is not possible to achieve significant light chain restriction (above a λ to κ ratio of 2 or a κ to λ ratio of 3) if the ratio of malignant B cells to benign B cells is less than approximately 1.5. It seems likely that the benign B cells “swamp” any light chain restriction in the neoplastic B cells, rendering it undetectable. In our laboratory, less than 0.5% of B cell lymphomas fail to show light chain restriction on IFC that is technically adequate, if T cell rich large B cell lymphomas are excluded. It has been suggested that light chain restriction can be demonstrated in T cell rich large B cell lymphoma by selectively gating the larger B cells.7 However, this first requires the diagnosis of T cell rich large B cell lymphoma to be suspected. In addition, when this strategy was attempted on the stored data from our cases it was possible to demonstrate light chain restriction in only one of the five cases (case 38; κ to λ ratio of 30).

Figure 3.

A paraffin wax embedded section of a T cell rich large B cell lymphoma that has been immunostained for CD20. There are approximately as many malignant (large) B cells as there are benign (small) B cells. If the ratio of malignant B cells to benign B cells is less than approximately 1.5, then light chain restriction will not be detectable in the B cell population as a whole.

“It is not possible to achieve significant light chain restriction if the ratio of malignant B cells to benign B cells is less than approximately 1.5”

In conclusion, FNA diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma was possible with IFC, cell block IHC, and FISH for c-myc alteration. It was difficult to make a definite diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma and mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma on FNA alone. Both tend to be sclerotic tumours and FNA tends to yield scanty neoplastic cells. The FNA diagnosis of peripheral T cell lymphoma depended on cell block IHC. IFC was not usually useful. T cell rich large B cell lymphomas did not show light chain restriction on IFC of FNA samples, probably because of frequent reactive B cells in the tumour. FNA is established as an accurate method of diagnosing and typing common forms of lymphoma. However, our study shows that Hodgkin lymphoma, mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma, and T cell rich large B cell lymphoma are often difficult to diagnose accurately on FNA cytology, even with the use of IFC and cell block IHC.

Abbreviations

FNA, fine needle aspiration

FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridisation

IFC, immunoflow cytometry

IHC, immunohistochemistry

PBS, phosphate buffered saline

REFERENCES

- 1.Sneige N. Diagnosis of lymphoma and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia by immunocytochemical analysis of fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol 1990;6:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robins DB, Katz RL, Swan F Jr, et al. Immunotyping of lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration. A comparative study of cytospin preparations and flow cytometry. Am J Clin Pathol 1994;101:569–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steel BL, Schwartz MR, Ramzy I. Fine needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy in 1,103 patients. Role, limitations and analysis of diagnostic pitfalls. Acta Cytol 1995;39:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart CJ, Duncan JA, Farquharson M, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of malignant lymphoma and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. J Clin Pathol 1998;51:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young NA, Al-Saleem TI, Ehya H, et al. Utilization of fine-needle aspiration cytology and flow cytometry in the diagnosis and subclassification of primary and recurrent lymphoma. Cancer 1998;84:252–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayall F, Dray M, Stanley D, et al. Immunoflow cytometry and cell block immunohistochemistry in the FNA diagnosis of lymphoma: a review of 73 consecutive cases. J Clin Pathol 2000;53:451–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young NA, Al-Saleem T. Diagnosis of lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration cytology using the revised European–American classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Cancer 1999;87:325–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mourad WA, Tulbah A, Shoukri M, et al. Primary diagnosis and REAL/WHO classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration: cytomorphologic and immunophenotypic approach. Diagn Cytopathol 2003;28:191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayall F, Chang B, Darlington A. A review of 50 consecutive cytology cell block preparations in a large general hospital. J Clin Pathol 1997;50:985–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chhieng DC, Cangiarella JF, Symmans WF, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of Hodgkin lymphoma: a study of 89 cases with emphasis on false-negative cases. Cancer 2001;93:52–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yatabe Y, Suzuki R, Matsuno Y, et al. Morphological spectrum of cyclin D1-positive mantle cell lymphoma: study of 168 cases. Pathol Int 2001;51:747–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Shanqeety O, Mourad WA. Diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration biopsy: a cytomorphologic and immunophenotypic approach. Diagn Cytopathol 2000;23:375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao JL, Cangiarella JF, Cohen JM, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of peripheral T-cell lymphomas. A cytologic and immunophenotypic study of 33 cases. Cancer 2001;93:151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]