Abstract

Background/Aims: Laminin and collagen IV have been proposed as extracellular matrix serum markers. Because fibrosis is a major complication of inflammatory bowel disease, serum concentrations of laminin and collagen IV were measured in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) and compared with inflammatory and healthy controls.

Methods: Laminin and collagen IV serum concentrations were measured in 170 patients with inflammatory bowel disease (86 UC and 84 CD), in 23 patients with other causes of intestinal inflammation, and in 80 matched healthy controls using commercially available enzyme linked immunosorbent assays. Laminin and collagen IV concentrations were correlated with disease activity, type, localisation, and treatment.

Results: Mean (SD) serum laminin concentrations were 281.0 (110.1) ng/ml in patients with UC, 275.6 (106.7) ng/ml in patients with CD, 192.0 (17.8) ng/ml in healthy controls, and 198.5 (32.5) ng/ml in inflammatory controls. Mean (SD) serum collagen IV concentrations were 72.8 (22.9) ng/ml in patients with UC, 71.0 (18.2) in patients with CD, 79.8 (12.2) ng/ml in healthy controls, and 88.9 (24.6) ng/ml in inflammatory controls. There was a significant difference among the four groups (p < 0.0001) for both markers. There was a strong correlation between serum laminin, but not collagen IV, and disease activity in both diseases. No significant association was found between these markers and disease localisation or disease type.

Conclusions: Serum concentrations of laminin are increased, whereas serum concentrations of collagen IV are decreased, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. They may be useful surrogate markers for sustained inflammation and tissue remodelling.

Keywords: collagen, Crohn’s disease, fibrosis, laminin, ulcerative colitis

The cellular mediators of intestinal fibrosis and the relation between fibrosis and normal repair are not well understood. It has been suggested that the initiation of a fibrotic process is a part of the intestinal response to chronic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1,2 Intestinal fibrosis is characterised by excessive production of extracellular matrix components. The cells in the tissue are constantly interacting with these extracellular matrix proteins and this interaction is essential for cellular functions. Important extracellular matrix glycoproteins are fibronectin, vitronectin, and laminin. Strictures in Crohn’s disease (CD) have been found to have a large accumulation of mast cells colocalised with laminin, but not with fibronectin and vitronectin.3 Laminin is a ubiquitous basement membrane component that plays a central role in maintaining the structure and function of basement membranes.4 Raised serum laminin concentrations have been found in various diseases.5–7 In a recent study, serum laminin was found to be increased in IBD with hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders compared with patients without these complications.8

“Raised serum laminin concentrations have been found in various diseases”

Collagen IV is also a major component of basement membranes and it has been used as an accurate extracellular matrix serum marker in liver diseases5 and in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis.9 Altered collagen metabolism has been suggested in IBD, mainly in CD.10

The aim of our study was to measure the serum concentrations of laminin and collagen IV in Greek patients with IBD. We evaluated the significance of these markers in relation to disease activity and the clinical characteristics of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

One hundred and seventy consecutive patients with IBD followed up at the department of gastroenterology of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, were included in our study (table 1). Patients with IBD (mean age, 46 years; 94 males and 76 females) were compared with 80 healthy controls (HCs), who were matched to the patient population for age and sex (mean age, 47 years; 47 males and 33 females). HCs were recruited from healthy blood donors, healthy visitors of hospital wards (gynaecology/obstetrics and orthopaedics), and normal hospital personnel. In addition, 23 patients with non-IBD intestinal inflammation (mean age, 50 years; 12 males and 11 females) were used as inflammatory controls. There were six patients with infectious colitis, seven with ischaemic colitis, and 10 with diverticulitis. Sera were collected from the 170 patients with IBD, the 23 inflammatory controls, and the 80 HCs. The diagnosis of UC and CD was based on standard criteria.11 Seven of the 170 patients with IBD (five with UC and two with CD) had an established diagnosis, by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Disease activity in CD was evaluated by means of the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) score,12 and in UC by the simple clinical colitis activity index (SCCAI).13 Patients with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer were excluded. Patients with liver disease other than primary sclerosing cholangitis were also excluded, and these comprised six cases (three alcoholic, two viral hepatitis). With regard to colorectal cancer, all patients with IBD were under a surveillance programme, with regular colonoscopies and biopsies. Standard laboratory parameters including red and white blood cell count, haemoglobin, haematocrit, platelet count, albumin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C reactive protein (CRP) were routinely determined in all patients. All serum samples were stored at −70°C until assayed. Our study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Crete.

Table 1.

Clinical details of the patients included in our study

| UC | CD | Total | |

| Number | 86 | 84 | 170 |

| Male | 55 | 39 | 94 |

| Female | 31 | 45 | 76 |

| Active | 39 | 28 | 67 |

| Inactive | 47 | 56 | 103 |

| Mean disease duration (years) | 7.7 | 8.5 | 8.1 |

| Disease localisation | |||

| Proctitis (UC)/ileum (CD) | 11 | 21 | |

| Left sided colitis (UC)/colon (CD) | 48 | 27 | |

| Total colitis (UC)/ileum+colon (CD) | 27 | 36 | |

| Disease type (CD) | |||

| Stenoting | 28 | ||

| Fistulising | 17 | ||

| Inflammatory | 39 | ||

| Current treatment* | |||

| Salazopyrine | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| 5-Aminosalicylic acid | 62 | 49 | 111 |

| Oral steroids | 19 | 20 | 39 |

| Topical steroids | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| Azathioprine | 7 | 18 | 25 |

| Methotrexate | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Infliximab | 1 | 11 | 12 |

| Metronidazole | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| None | 7 | 6 | 13 |

*Some patients received more than one drug.

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Laboratory studies

Serum laminin was determined in all patients with IBD and controls by means of a commercially available assay (QuantiMatrixTM human laminin enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kit; Chemicon International, Temecula, California, USA). Serum collagen IV was also measured by Biotrin Collagen IV enzyme immunoassay (Biotrin International GmbH, Sinsheim-Reihen, Germany), which is a one step sandwich enzyme immunoassay that uses a pair of monoclonal antibodies to recognise different antigenic sites on collagen IV. When a specimen is measured simultaneously more than eight times with these assays, the coefficient of variance for the measured value is less than 12% and 15% for laminin and collagen IV, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean (SD). Comparisons between the four diagnostic groups in terms of continuous measurements were made by the Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric ANOVA). Post hoc multiple comparison tests were made by Dunn’s test. The same tests were used for the comparisons between the groups of disease localisation. Comparisons between two groups (active versus non-active disease, stenotic versus non-stenotic CD, etc) were made by means of the Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test. The Kolmogorov and Smirnov test was used to assess the assumption that data were sampled from populations that have Gaussian distributions. The association between serum laminin or collagen IV and disease activity indices or other laboratory parameters was examined by linear regression analysis. The evaluation of linearity was done by the Runs test. A level of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

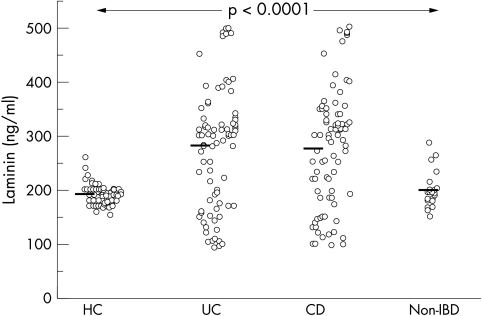

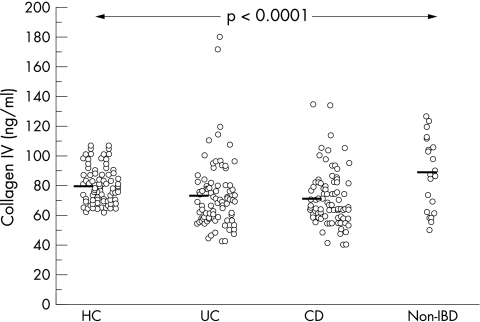

Figures 1 and 2 show the distribution of laminin and collagen IV in patients and controls. Mean (SD) serum laminin concentrations were 281.0 (110.1) ng/ml in patients with UC, 275.6 (106.7) ng/ml in patients with CD, 192.0 (17.8) ng/ml in healthy controls, and 198.5 (32.5) ng/ml in patients with non-IBD intestinal inflammation. A significant difference between the mean concentrations of laminin in the four groups was found (p < 0.0001). The multiple comparisons Dunn’s test showed that patients with UC and CD had similar average concentrations of laminin (p > 0.05). Similarly, laminin concentrations did not differ between the two groups of controls (HC and non-IBD). Patients with UC and CD had significantly higher laminin concentrations than both groups of controls (UC v HC, p < 0.001; UC v non-IBD, p < 0.01; CD v HC, p < 0.001; CD v non-IBD, p < 0.01). One hundred and twenty one patients with IBD (61 UC, 60 CD; 71.2%) had laminin concentrations above the 95th centile of matched healthy controls. In contrast, mean (SD) serum collagen IV concentrations were 72.8 (22.9) ng/ml in patients with UC, 71.0 (18.2) in patients with CD, 79.8 (12.2) ng/ml in healthy controls, and 88.9 (24.6) ng/ml in patients with non-IBD intestinal inflammation. Patients with UC and CD had significantly lower serum collagen IV concentrations than did healthy and inflammatory controls. There was a significant difference between the mean concentrations of collagen IV in the four groups (p < 0.0001). The multiple comparisons Dunn’s test showed that the UC and CD groups had similar average collagen IV concentrations (p > 0.05), as did the two groups of controls (HC and non-IBD). Patients with UC and CD had significantly lower collagen IV concentrations than both groups of controls (UC v HC, p < 0.001; UC v non-IBD, p < 0.01; CD v HC, p < 0.001; CD v non-IBD, p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

The distribution of laminin in healthy controls (HC, n = 80), and patients with ulcerative colitis (UC, n = 86), Crohn’s disease (CD, n = 84), and non-inflammatory bowel disease (non-IBD) (n = 23). Each individual patient or control is shown as a circle; the bold lines are mean values.

Figure 2.

The distribution of collagen IV in healthy controls (HC, n = 80), and patients with ulcerative colitis (UC, n = 86), Crohn’s disease (CD, n = 84) and non-inflammatory bowel disease (non-IBD) (n = 23). Each individual patient or control is shown as a circle; the bold lines are mean values.

With regard to disease activity, serum laminin concentrations were significantly higher in the active phase in patients with UC (mean, 309.1; SD, 103.5 ng/ml) than in the inactive phase (mean, 257.6; SD, 110.8 ng/ml; p = 0.03; unpaired t test). The data were normally distributed (Kolmogorov and Smirnov test, p > 0.10). Similarly, in patients with CD, mean (SD) laminin concentrations were 315.2 (134.1) ng/ml in active disease, significantly higher than those seen in non-active disease (mean, 256.0; SD, 84.6 ng/ml; p = 0.04; unpaired t test with Wech correction; normality test of Kolmogorov and Smirnov, p > 0.10). Mean serum collagen IV concentrations were not significantly different between the active and inactive phase of both diseases (UC: Mann-Whitney U statistic, 723.5; p = 0.5; CD: Mann-Whitney U statistic, 661; p = 0.21).

Serum laminin concentrations were lower in patients with proctitis than in those with left sided or extensive colitis, although the difference was not significant (p = 0.26). In addition, patients with CD who had an ileum localisation had higher laminin concentrations (mean, 290.9.3; SD, 90.1 ng/ml) than those with ileocolonic (mean, 279.9.5; SD, 85.2 ng/ml) and colonic disease (mean, 257.7; SD, 128.8 ng/ml), but again the differences were not significant (p = 0.4)

Subsequent analyses of other subgroups revealed no significant correlation between serum laminin or collagen IV concentrations and disease type (stenotic versus non-stenotic), years of diagnosis (early versus late disease), smoking habits, and the current use of medications such as 5-aminosalicylic acid, prednisone, and azathioprine. Patients with IBD and primary sclerosing cholangitis (seven patients) had significantly higher collagen IV concentrations (mean, 105.9; SD, 35.9 ng/ml), but similar laminin concentrations (mean, 283.9; SD, 133.5 ng/ml), compared with patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Serum laminin was positively correlated with CRP (r = 0.46; p = 0.02) and negatively with albumin (r = −0.54; p = 0.006). No significant deviation from linearity was found using Runs test. Conversely, no correlation between serum collagen IV and CRP or albumin was found. No correlation between serum laminin or collagen IV and clinical indices of activity (CDAI and SCCAI) was found.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that serum concentrations of laminin are increased in patients with IBD, whereas those of collagen IV are decreased. The measurement of circulating connective tissue metabolites has been suggested as a useful tool for the assessment of fibroproliferative activity in various diseases. The longstanding inflammation seen in inflammatory bowel disease may induce prolonged repair processes, causing irreversible changes in the tissue architecture and stricture formation. The degree and distribution of inflammatory cell infiltrates may determine the clinical outcome in IBD, including the increased submucosal collagen observed in UC14 and the transmural fibrosis, stenosis, and obstruction that are frequently complications of CD.3

Take home messages.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) have increased serum concentrations of laminin but decreased serum concentrations of collagen IV

Concentrations of serum laminin, but not collagen IV, correlated with disease activity in both diseases

There was no significant association between these markers and disease localisation or disease type

These proteins may be useful surrogate markers for sustained inflammation and tissue remodelling

Laminin, the major non-collagenous component of the basement membrane, plays an important role in epithelial basal lamina formation and promotes the differentiation of human enterocytes. In a recent study, no positive immunoreactivity against laminin was seen in epithelial basement membranes surrounding the crypts in colonic tissues affected by UC.15 Serum laminin has been found to be increased in patients with IBD who also have hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders, compared with those without these complications,8 although this study was limited by the absence of healthy or inflammatory controls. Our study is the first in which the serum laminin concentrations of patients with IBD, patients with other causes of intestinal inflammation, and healthy controls are compared. We found that raised serum laminin concentrations in patients with IBD were associated with disease activity, but not with hepatobiliary disorders. Circulating laminin, which is relatively resistant to degradation by proteases, may possibly reflect basement membrane degradation, although this is not verified by the concentrations of collagen IV, which is also a basement membrane element. It could be an indicator of vascular endothelial cell damage, and this should be further investigated.

“We found that raised serum laminin concentrations in patients with IBD were associated with disease activity, but not with hepatobiliary disorders”

Recent studies have shown that propeptides of procollagen I and III were decreased, whereas the C-terminal propeptide of collagen I was increased, in the peripheral and splanchnic circulation of patients with CD when compared with healthy controls.10,16 To our knowledge, there are no published data on circulating collagen IV in IBD. Collagen IV accumulation has been found in tissue samples from patients with UC.15 Our data provide further evidence of altered collagen metabolism in IBD. The finding of low serum collagen IV in IBD could be explained by the suggestion that this molecule is retained or degraded locally, resulting in a decreased escape rate into the circulation.

In conclusion, the measurement of serum laminin and collagen IV may be useful surrogate markers for sustained inflammation and tissue remodelling in inflammatory bowel disease.

Abbreviations

CD, Crohn’s disease

CDAI, Crohn’s disease activity index

CRP, C reactive protein

HC, healthy control

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease

SCCAI, simple clinical colitis activity index

UC, ulcerative colitis

REFERENCES

- 1.Pucilowska JB, Williams KL, Lund PK. Fibrogenesis. IV. Fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease: cellular mediators and animal models. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;279:G653–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrance IC, Maxwell L, Doe W. Altered response of intestinal mucosal fibroblasts to profibrogenic cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2001;7:226–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelbmann CM, Mestermann S, Gross V, et al. Strictures in Crohn’s disease are characterised by an accumulation of mast cells colocalised with laminin but not with fibronectin or vitronectin. Gut 1999;45:210–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timpl R, Rohde H, Robey PG, et al. Laminin—a glycoprotein from basement membranes. J Biol Chem 1979;254:9933–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh KM, Fletcher A, MacSween RN, et al. Basement membrane peptides as markers of liver disease in chronic hepatitis. C J Hepatol 2000;32:325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakano T, Iwahashi N, Maeda J, et al. Serum laminin P1 in small cell lung cancer: a valuable indicator of distant metastasis? Br J Cancer 1992;65:608–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgmann H, Hollenstein U, Maca T, et al. Increased serum laminin and angiogenin concentrations in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:508–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heikius B, Niemela O, Niemela S, et al. Elevated serum PIIINP and laminin in inflammatory bowel disease indicate hepatobiliary and pancreatic dysfunction. Hepatogastroenterology 2002;49:404–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horslev-Petersen K, Bentsen KD, Halberg P, et al. Connective tissue metabolites in serum as markers of disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1988;6:129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kjeldsen J, Rasmussen M, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, et al. Collagen metabolites in the peripheral and splanchnic circulation of patients with Crohn disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:1193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1989;170:2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National cooperative Crohn’s disease study. Gastroenterology 1976;70:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 1998;43:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrance IC, Maxwell L, Doe W. Inflammation location, but not type, determines the increase in TGF-beta1 and IGF-1 expression and collagen deposition in IBD intestine. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2001;7:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmehl K, Florian S, Jacobasch G, et al. Deficiency of epithelial basement membrane laminin in ulcerative colitis affected human colonic mucosa. Int J Colorectal Dis 2000;15:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjeldsen J, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Junker P. Seromarkers of collagen I and III metabolism in active Crohn’s disease. Relation to disease activity and response to therapy. Gut 1995;37:805–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]