Abstract

Inflammatory pseudotumour is an uncommon mass forming lesion, representing the histological expression of an infective or reactive/reparative process (pseudotumour) in most cases, and a bona fide neoplasm (for example, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour) in a minority of cases. This report describes the case of an inflammatory pseudotumour with a pathology that unveiled proliferative CD68 positive and actin negative spindle shaped cells, with a mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate, and a culture that yielded an uncommon fastidious bacillus, Eikenella corrodens. The clinical course was indolent but protracted, with insidious progression to multifocal non-contiguous lesions, involving the lungs, liver, spleen, left kidney, and deep neck tissue, all of which responded to medical treatment with appropriate antibiotics. It is of paramount importance that clinicians search for an infective cause of an inflammatory pseudotumour, to ensure appropriate treatment.

Keywords: inflammatory pseudotumour, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, Eikenella corrodens, CD68, actin

Inflammatory pseudotumours (IPTs) have long been accepted as an aberrant or exaggerated response to tissue injury undergoing a chronic inflammatory process. Although IPTs usually have a benign evolution, with the occasional documented infective cause, the prognosis of a minority of cases is poor, and includes local recurrence, development of multifocal non-contiguous lesions, infiltrative local growth, vascular invasion, and malignant transformation, which seems contradictory to their purely inflammatory or reactive nature.1 This nosological category, which pathologists and clinicians have long been complacent in treating, is enigmatic and has recently resulted in the introduction of a plethora of alternative terminology for this fibroinflammatory disorder, including inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours (IMFTs). Eikenella corrodens is a rarely isolated Gram negative, facultatively anaerobic, fastidious bacillus.2–9 Although it is part of the normal flora of the human oral cavity, upper respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts,2–6 its potential to act as a pathogen has been well documented.2–6

“Although inflammatory pseudotumours usually have a benign evolution, with the occasional documented infective cause, the prognosis of a minority of cases is poor”

We report a case of IPT with a protracted neoplasm-like clinical course and culture isolated E corrodens, with the aim of alerting physicians to this uncommon opportunistic pathogen, the need for an appropriate antibiotic coverage, and the role of E corrodens as a possible aetiological agent in a still incomplete list of microorganisms implicated in IPTs with an infective origin.

CASE REPORT

A 46 year old woman initially presented to our pulmonary medicine clinic complaining of a productive cough with intermittent blood tinged sputum for more than six months’ duration. She had a known history of oesophageogastrectomy, with colon bypass for the treatment of chemical corrosive injuries caused by a suicide attempt more than one year before. Chest computerised tomography (CT) revealed consolidation in the left lower lobe of the lung, with volume reduction and several small low attenuated lesions in the spleen. She had no fever (37°C orally) and showed leucocytosis (15.62 × 103/μl) and neutrophilia (87.4%) in the peripheral blood. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was normal (2.2 ng/ml). Bronchoscopy disclosed an elevated lesion with surface erosion on the left main bronchial mucosa. Endobronchial biopsy showed acute suppurative inflammation, without granuloma or malignancy. Echo guided transpleural left lung biopsy revealed chronic inflammation and interstitial fibrosis, without granuloma or malignancy. Acid fast stains for mycobacteria in the sputum, bronchial washing/brushing specimens, and pulmonary biopsy tissue were all negative. She received a seven day course of oral kitasamycin (a macrolide antibiotic) and conservative symptomatic treatment before being lost to follow up.

The patient presented again to our gastrointestinal medicine clinic less than one year later as a result of intractable pain over the right upper abdomen and right lower chest. Sonography revealed two right hepatic masses and right lower lung consolidation. CT showed irregular heterogeneously enhancing masses in the right lower lung, a large irregular mass, measuring 9 × 7 × 4 cm, alongside several small irregular nodules, visible with heterogeneous contrast enhancement in the right liver (fig 1), in addition to several small, irregular nodules with similar characteristics in the left kidney and spleen. The left pulmonary lesion present one year earlier had resolved. A low grade fever (up to 37.7°C orally) and moderate leucocytosis (16.00 × 103/μl) with neutrophilia (87.4%) in the peripheral blood were present, although there were no toxic signs of sepsis. Serum CEA (3.74 ng/ml) and α fetoprotein (19.4 μg/litre) were also normal. An amoebic haemagglutination test was negative. Blood bacterial culture and sputum mycobacterial culture revealed no growth. An acid fast stain of the sputum for mycobacteria remained negative. Echo guided, core needle biopsy and fine needle aspiration of the liver were finally performed for pathological and microbiological studies to elucidate the multifocal and seemingly recurrent lesions.

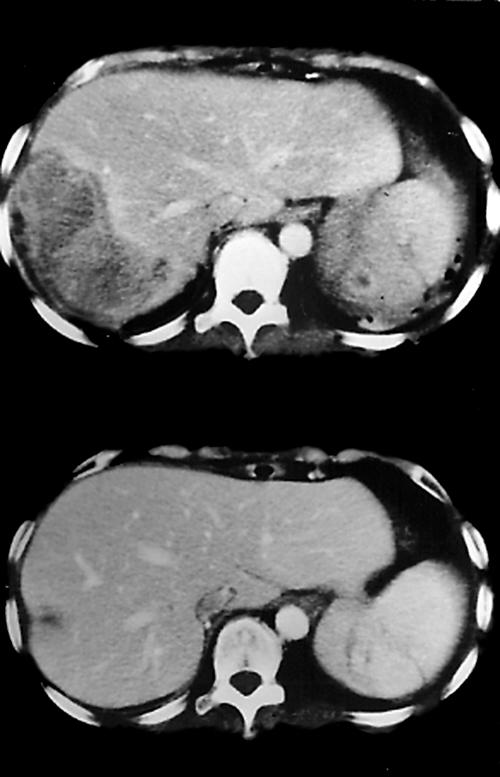

Figure 1.

The upper panel shows a computerised tomography (CT) scan revealing a heterogeneously enhancing hepatic mass in the right lobe, and a smaller lesion with irregular rim enhancement in the spleen. The lower panel shows a follow up CT scan three months later, which reveals nearly total resolution of the lesions.

Histopathology of the liver mass biopsy showed proliferation of benign spindle shaped cells and a minor component of inflammatory cells, consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes including xanthomatous cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils (fig 2), not greatly different from that seen in the previous lung biopsy, which disclosed acute and chronic inflammation with fibrosis. The impression was one of a chronic abscess with an exaggerated granulation tissue response. However, the hepatic mass showed a soft tissue density with heterogeneous contrast enhancement, instead of a water density with a well enhanced rim, which is usually seen in typical hepatic pyogenic or amoebic abscesses. It also yielded a scanty amount of fluid, in contrast to the usual abscess aspirate, and there was a clinical impression that it might be a metastatic neoplasm. Taken together, these findings indicated that it might be more than just a chronic abscess. In addition, some cases of IMFT with low grade malignant potential do display granulation tissue-like spindle cell proliferation and a pseudotumour-like appearance. Immunohistochemical studies of the liver tissue and previous lung biopsies were performed to clarify the nature of the proliferative spindle shaped cells, which were positive for vimentin/CD68 and negative for muscle specific actin/desmin/CD21. The proliferation of CD68 positive spindle shaped histiocytes instead of actin positive myofibroblasts, along with the presence of neutrophils, implied an infective process, rather than a bona fide neoplasm. Meanwhile, a bacterial culture of the liver aspirate was performed to identify the aetiological source of the infection. It was initially negative, but after five days of inoculation, 1 mm pale yellow colonies were present in the plates of blood agar and eosin methylene blue agar, along with growth in the thioglycolate broth. The colonies had a characteristic morphology that appeared to corrode or pit the blood agar surfaces without haemolysis, and were found to consist of Gram negative bacilli microscopically. Biochemical assays showed that the organisms were catalase (−), oxidase (+), ornithine reaction (+), esculin reaction (−), and non-saccharolytic in the triple sugar iron agar; in addition, bacterial growth was seen in the presence of X or X/V factors, but no growth was seen when only V factor was present. A constellation of colony characteristics and biochemical assays indicated that the organism was E corrodens,2,9 and antibiotic sensitivity testing proved that it was susceptible to cefixime, cefotaxime, ceftizoxime, cefpodoxime, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, and amoxicillin-clavulanate, and resistant to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Echo guided transpleural biopsy of the right lung was also performed and showed a similar fibroinflammatory lesion, with an identical immunohistochemical profile to the lesions found in the liver and left lung. The patient initially received intravenous cefuroxime and metronidazole, and was switched to amoxicillin-clavulanate soon afterwards, following the antibiotic sensitivity test; the patient was discharged after improvement.

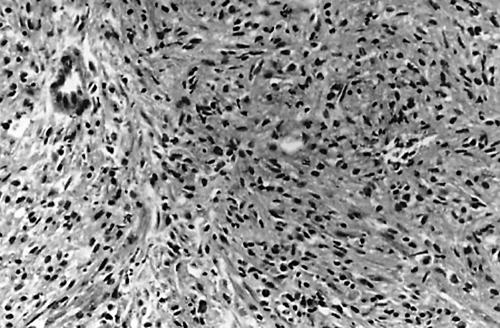

Figure 2.

Proliferation of spindle shaped cells in a vaguely fascicular pattern with focal entrapment of a bile ductule in the hepatic inflammatory pseudotumour (haematoxylin and eosin stained; original magnification, ×200).

Unfortunately the patient revisited our otolaryngology clinic one month later, presenting with a left submandibular mass and mild fever (37.3°C orally). The peripheral blood revealed mild leucocytosis (white blood cell count, 10.66 × 103/μl) with neutrophilia (82.2%). Neck CT showed a strongly and heterogeneously enhancing mass, measuring 2.7 × 1.7 cm, located inferior to the left mandibular angle. Again, biopsy disclosed a similar histopathology to the previous lesions, and an identical immunohistochemical profile. Intravenous amoxicillin-clavulunate was administered. The patient was followed up without recurrence for more than 19 months, during which CT showed nearly complete resolution of all the lesions in the lungs, liver (fig 1), spleen, and kidney.

DISCUSSION

Eikenella corrodens is a rare contributor to liver abscess,5 in that the most frequently isolated pathogen in our microbiology laboratory during the past decade was Klebsiella pneumoniae. It is a fastidious, slow growing, human commensal bacillus, capable of acting as an opportunistic pathogen and causing abscesses in several anatomical sites, including the liver,3–5 lung,6 spleen,7 and submandibular region,8 as demonstrated by our present case. The patient’s previous oesophageogastrectomy with colon bypass for her corrosive injuries may have contributed to bacterial spreading via the damaged gastrointestinal mucosal barrier. The unique feature of this case is its indolent and protracted clinical course, with a multifocal metastasis-like lesion and a distinct proliferation of spindle shaped histiocytes simulating a neoplasm. The identification of E corrodens may be delayed because of its slow growth in the absence of CO2.5 Previous trials have reported it to be resistant to clindamycin,3–6 metronidazole,3–6 and aminoglycosides,4,6 but sensitive to penicillin,5,6 ampicillin,6 chloramphenicol,4,6,7 and tetracycline.4,6 The later development of the left submandibular mass suggested that a more prolonged course of antibiotic treatment was needed to eradicate the residual microorganisms in the chronic abscess with pronounced fibrosis.

IPT is the morphological manifestation of aetiologically diverse processes with spindle cell proliferation and a variable number of inflammatory cells. There is compelling evidence that some of these fibroinflammatory masses are infection associated and often characterised by a proliferation of spindle shaped histiocytes and/or dendritic cells, in contrast to a myofibroblastic proliferation in the other IPTs, also known as IMFT.10

“The later development of the left submandibular mass suggested that a more prolonged course of antibiotic treatment was needed to eradicate the residual microorganisms in the chronic abscess with pronounced fibrosis”

Whereas histomorphology is of limited use in differentiating neoplastic spindle cells from reactive ones, immunological studies help differentiate CD68 positive spindle shaped histiocytes from actin positive myofibroblasts, although the presence of actin positive myofibroblasts does not amount to a truly neoplastic process. Because the term IPT denotes a more reactive or reparative process than does IMFT, which confers a neoplastic diagnosis, we are of the opinion that IMFT cannot be diagnosed until the immunohistochemical identification of actin positive spindle cells or myofibroblasts. A seemingly spontaneous resolution of the left pulmonary lesion, with recurrence of multifocal non-contiguous lesions, in our case did not amount to a de facto neoplasm. Some IPTs are thought to have a bacterial aetiology but this may fail to be confirmed by culture because fastidious species are often involved. It is crucial to search for an infective origin, especially bacterial, in patients with IPT, because a lack of appropriate antibiotic treatment in bacteria associated IPT may result in clinical complications.

Take home messages.

Inflammatory pseudotumour (IPT) is a rare mass forming lesion, which is the result of an infective or reactive/reparative process (pseudotumour) in most cases, but is a true neoplasm in a few cases

We describe an IPT, which gave the clinical impression of a metastatic neoplasm, but from which an uncommon fastidious bacillus, Eikenella corrodens, was cultured

The clinical course was indolent but protracted, and the numerous lesions responded to treatment with the appropriate antibiotics

It is extremely important that clinicians search for an infective cause of IPT (particularly because fastidious species are often involved) to ensure that appropriate treatment is given

Abbreviations

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen

CT, computed tomography

IMFT, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour

IPT, inflammatory pseudotumour

REFERENCES

- 1.Coffin CM, Humphrey PA, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, a clinical and pathological survey. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manuselis G Jr. Utilization of colonial morphology for the presumptive identification of microorganisms. In: Mahon CR, Manuselis G Jr, eds. Textbook of diagnostic microbiology, 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders, 1995:307–38.

- 3.Massey BT. Eikenella corrodens isolated from a polymicrobial hepatic abscess. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;84:1100–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinlivan D, Davis TME, Daly FJ, et al. Hepatic abscess due to Eikenella corrodens and Streptococcus milleri, implications for antibiotic therapy. J Infect 1996;33:47–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnon R, Ruzai-Shapiro C, Salen E, et al. A rare pathogen in a polymicrobial hepatic abscess in an adolescent. Clin Pediatr 1999;38:429–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu CY, Liu LL, Luh KT. Lung abscess caused by Eikenella corrodens, report of a case. J Formos Med Assoc 1989;88:828–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez-Pomata MT, Dominguez J, Horcajo P, et al. Splenic abscess caused by Eikenella corrodens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1992;11:162–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heymann WR, Drezner D. Submandibular abscess caused by Eikenella corrodens. Cutis 1997;60:101–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall GS. Nonfermenting Gram-negative bacilli and miscellaneous Gram-negative rods. In: Mahon CR, Manuselis G Jr, eds. Textbook of diagnostic microbiology, 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders, 1995:513–38.

- 10.Dehner LP. The enigmatic inflammatory pseudotumors, the current state of our understanding and misunderstanding. J Pathol 2000;192:289–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]