Abstract

Background: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) became a worldwide outbreak with a mortality of 9.2%. This new human emergent infectious disease is dominated by severe lower respiratory illness and is aetiologically linked to a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV).

Methods: Pulmonary pathology and clinical correlates were investigated in seven patients who died of SARS in whom there was a strong epidemiological link. Investigations include a review of clinical features, morphological assessment, histochemical and immunohistochemical stainings, ultrastructural study, and virological investigations in postmortem tissue.

Results: Positive viral culture for coronavirus was detected in most premortem nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens (five of six) and postmortem lung tissues (two of seven). Viral particles, consistent with coronavirus, could be detected in lung pneumocytes in most of the patients. These features suggested that pneumocytes are probably the primary target of infection. The pathological features were dominated by diffuse alveolar damage, with the presence of multinucleated pneumocytes. Fibrogranulation tissue proliferation in small airways and airspaces (bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia-like lesions) in subpleural locations was also seen in some patients.

Conclusions: Viable SARS-CoV could be isolated from postmortem tissues. Postmortem examination allows tissue to be sampled for virological investigations and ultrastructural examination, and when coupled with the appropriate lung morphological changes, is valuable to confirm the diagnosis of SARS-CoV, particularly in clinically unapparent or suspicious but unconfirmed cases.

Keywords: pulmonary, severe acute respiratory syndrome, coronavirus

During the spring of 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) became a worldwide outbreak affecting more than 8000 patients from over 30 countries, with a mortality of 9.2%.1 The disease represents a new human emergent infectious disease dominated by severe lower respiratory tract illness. SARS is aetiologically linked to a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV).2–7 Most patients show chest x ray (CXR) abnormalities at presentation, with patchy airspace disease.8,9 Computed tomography often reveals a distinct subpleural ground glass appearance.8,9 In those patients who deteriorate, the radiological changes progress to bilateral involvement and resemble adult respiratory distress syndrome.8,9 Here, we report the pulmonary pathology findings in seven fatal cases of SARS in the major hospital outbreak in Hong Kong.8

“Severe acute respiratory syndrome is aetiologically linked to a new coronavirus”

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Case selection

The chain of events that led to the outbreak in Hong Kong and various countries has been described.8–12 Our index patient was a 26 year old man with a history of contact with the first index case when staying in the same hotel.8,10 We describe seven patients who died of SARS, six of whom stayed in the same ward as our index patient and one who had previous contact with the index patient in the accident and emergency department. SARS was diagnosed according to the World Health Organisation criteria.13 Routine microbiological investigations, including serology, were performed on these patients. All seven patients eventually succumbed and necropsies were performed.

SARS-CoV isolation

Virus isolation was performed using African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells. When a diffuse, refractile, rounding, cytopathic effect was noted, the Vero cell culture supernatant was passaged to a fresh Vero cell culture tube to ensure reproducibility of the cytopathic effect. SARS-CoV in the supernatant was further confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using primers described previously.14

Necropsy and histological assessments

Full necropsies (excluding the brain) were performed in patients 1–6. A limited necropsy (lung and heart) was performed in patient 7. Sections (4 μm thick) were prepared from the 10% formalin fixed, routinely processed, paraffin wax embedded blocks and were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. The following histochemical stainings were performed: periodic acid Schiff, Grocott’s hexamine silver, Gram, Ziehl Neelsen, Warthin Starry, and Masson’s trichrome. The standard avidin–biotin method was used for immunohistochemical study using markers for herpes simplex virus (HSV; BioGenex, San Ramon, California, USA; 1/200 dilution), cytomegalovirus (CMV; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; 1/25 dilution), lymphoid marker (CD45; Dako; 1/150 dilution), B cell marker (L26; Dako; 1/240 dilution), T cell marker (CD3; Dako; 1/200 dilution), natural killer cell marker (CD56; Monosan, Uden, the Netherlands; 1/200 dilution), histiocyte markers (CD68; clone KP1; Dako; 1/2000 dilution; Mac 387; Dako; 1/400 dilution), and epithelial marker (cytokeratin; AE1/AE3; Dako; 1/100 dilution). Postmortem lung tissues were also fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for routine transmission electron microscopy (EM).

Statistical analysis

Spearman analysis was used to study the correlation between duration of illness and various pathological features with commercial statistical software (Statistical Package for Social Science, SPSS, version 10.1.0) and p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Clinical data

There were six male patients and one female patient, who had an age range from 44 to 81 years (mean, 71); all had pre-existing medical illnesses (table 1) and CXR abnormality at disease onset. The duration of illness ranged from four to 20 days (median, 11). Six patients received high dose intravenous ribavirin (range, 1–14 days; median, 9.5). Five patients received intravenous steroids (range, 4–16 days; median, 10). Six of the seven patients were intubated and mechanically ventilated (range, 1–16 days; median, 10). Apart from the isolation of SARS-CoV from nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens of patients 1–3, 5, and 7 (five of six; table 1), other microbiological investigations, including the isolation of metapneumovirus, were negative.8,15 Bacterial cultures were positive in five patients at the terminal stage. Staphylococcus aureus (patients 2 and 3) and enterococcus (patient 6) were isolated from blood culture. Klebsiella sp (patient 1) and stenotropnomas (patient 7) were identified in tracheal aspirate specimens. All patients died of respiratory failure, with concurrent congestive heart failure, hepatic encephalopathy, and acute renal failure in patients 1, 2, and 5, respectively.

Table 1 .

Clinical features of seven patients who died of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

| Patients | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Age | 69 | 64 | 76 | 81 | 44 | 79 | 81 |

| Sex | M | M | M | F | M | M | M |

| Premorbid disease | CVS | CLD | MDS | COAD | CLD | CVS | HT |

| Illness (days*) | 4 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 16 | 19 | 20 |

| Ribavirin (days*) | 1 | 4 | 7 | No | 12 | 14 | 14 |

| Hydrocortisone (days*) | No | 4 | 7 | No | 10 | 15 | 16 |

| Intubation (days*) | 1 | 6 | 8 | No | 12 | 15 | 16 |

| Viral isolation | |||||||

| NPA | + | + | + | NA | + | − | + |

| Lung | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Small intestine | + | + | + | + | + | − | NA |

| Lung EM | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

CLD, chronic liver disease; COAD, chronic obstructive airway disease; CVS, cardiovascular disease; EM, electron microscopy for SARS associated coronavirus CoV; HT, hypertension; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; NA, not available; NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirate.

*Duration of illness or treatment.

CoV isolation

Postmortem lung, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and small intestine tissues were available for viral isolation from patients 1–6 and lung and heart tissues were available from patient 7. SARS-CoV was isolated in culture from postmortem lung tissues in patients 1 and 2 (two of seven) and from small intestinal tissue in patients 1–5 (five of six). Transmission EM demonstrated viral particles in patients 1–4, 6, and 7 (six of seven; table 1).

Pulmonary pathology

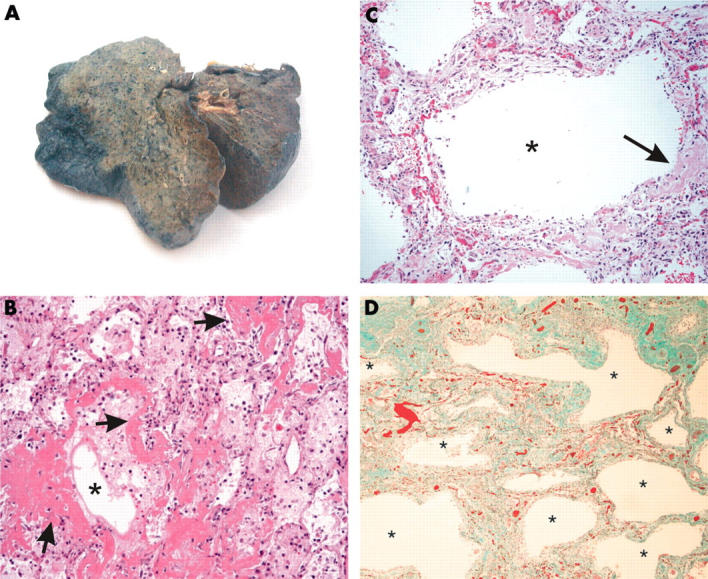

The upper respiratory tract was unremarkable. The lungs were heavy (650–1200 g), with a mild pleural effusion of clear serous fluid (50–200 ml on each side), pronounced pulmonary oedema, and extensive consolidation (fig 1A). Focal haemorrhage was seen in some cases. Apart from one case with apical pleural adhesion, pleuritis was not apparent. Mild and small pulmonary thromboembolism was only noted in patient 7. Peribronchial or hilar lymph nodes were not enlarged.

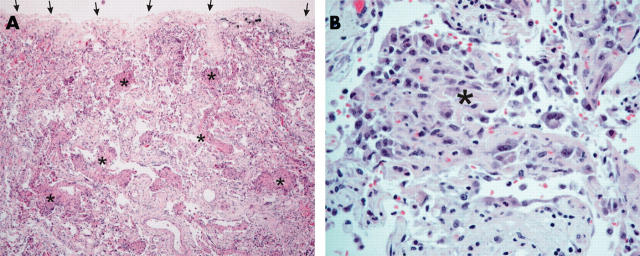

Figure 1.

Gross and histological features of lungs in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. (A) Extensive consolidation with a greyish cut surface was noted in most of the patients. (B) All the patients showed features of the acute phase of diffuse alveolar damage, with pulmonary oedema and formation of a hyaline membrane. The airspaces are indicated by asterisks and some of the hyaline membranes lining the alveolar spaces are highlighted by arrows (haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×100). (C) Mild infiltrate of interstitial inflammatory cells with interstitial thickening, accompanied by dilated airspaces (the asterisk indicates the dilated airspace). A small amount of hyaline membrane, as indicated by the arrow, was still evident (haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×100). (D) Pronounced interstitial fibrosis with honeycombing was noted in patient 7 (asterisks indicated the abnormally dilated airspaces; Masson’s trichrome stain; original magnification, ×40).

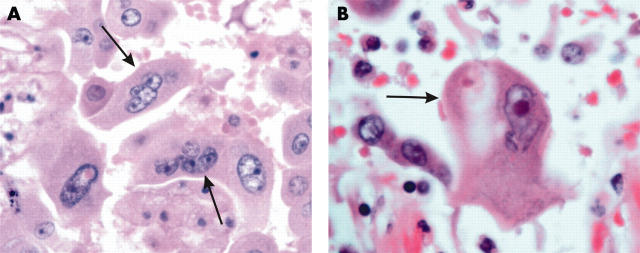

Histologically, all patients had features of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) with pronounced pulmonary oedema and hyaline membrane formation (table 2; fig 1B). In some areas, there was interstitial thickening, with mild to moderate fibrosis, but a disproportionately sparse infiltrate of inflammatory cells (mainly histiocytes, including multinucleated forms, and lymphocytes). Dilatation of the airspaces was seen (fig 1C), as was focal honeycombing fibrosis (patient 6; fig 1D). Intra-alveolar organisation of exudates was seen and, in four cases, there was formation of granulation tissues in small airways and airspaces (fig 2A, B). These lesions were typically located in the subpleural region and the cellular component consisted mainly of histiocytes. The collection of acute inflammatory exudates in the airspaces was noted only in three patients with secondary bacterial infection (with positive premortem bacterial blood cultures). More unusually, atypical pneumocytes were seen in all seven patients, although the distribution was focal (fig 3). These atypical forms included multinucleated giant pneumocytes with irregularly distributed nuclei (fig 3A) or pneumocytes with large atypical nuclei, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, and granular amphophilic cytoplasm (fig 3B). However, distinct viral inclusions were not apparent. Among all the histological features investigated (table 2), a positive correlation was detected only between the duration of illness and the degree of interstitial fibrosis (Spearman correlation, p = 0.019). In the extrapulmonary organs, splenic white pulp lymphoid depletion was seen in all patients. Focal individual muscle fibre necrosis and regenerative changes were noted in four patients. Apart from the comorbid conditions, no other unique pathological features were found in other organs.

Table 2.

Summary of the pulmonary pathological features of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome

| Patients | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Atypical pneumocytes | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Diffuse alveolar damage | |||||||

| Pulmonary oedema | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Hyaline membrane | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Organising phase | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Interstitial fibrosis | + | + | + | + | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| BOOP-like | − | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Pulmonary haemorrhage | − | − | ++ | − | + | ++ | − |

| Bronchopneumonic changes | − | + | + | − | − | + | − |

+, mild; ++, moderate; +++, severe; −, not present.

BOOP-like, bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia-like lesion.

Figure 2.

Bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia (BOOP)-like lesion in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. (A) A BOOP-like lesion was evident with cellular organising plugs within the small airways and airspaces (asterisks indicate some of the lesions). Lesions were typically located in the subpleural region (the visceral pleural surface is indicated by arrows; haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×40). (B) Higher power view of cellular organising plugs (asterisk). The main cellular component consisted of histiocytes, which were CD68 positive (data not shown) (haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×200).

Figure 3.

Atypical pneumocytes in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. (A) Multi-nucleated giant pneumocytes with irregularly distributed nuclei were evident (indicated by arrows; haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×400). (B) A giant atypical pneumocyte with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli (indicated by arrow; haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ×400).

Histochemical and immunohistochemical studies

All the special histochemical stains for infective agents were negative except that Gram positive cocci were detected in the acute inflammatory cell infiltrate in patient 3. Immunohistochemical staining for CMV and HSV was negative. Some of the multinucleated cells with atypical nuclei were positive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), confirming their epithelial nature as pneumocytes. The inflammatory cell infiltrate included histiocytes (CD68 and Mac387 positive). The lymphoid infiltrate was sparse and consisted mainly of T cells (CD3 positive) and a few B cells (CD20 positive); natural killer cells (CD56 positive) were largely lacking.

Ultrastructural study

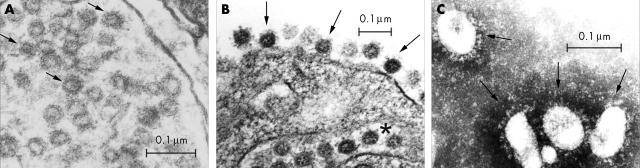

Pneumocytes containing viral-like particles were noted in most cases (six of seven), although such cells were scanty (fig 4A). The particles measured 60–90 nm in size and were found within dilated cytoplasmic vesicles, reminiscent of endoplasmic reticulum. The appearance of the viral-like particles was similar to that seen in the Vero cell culture (fig 4B, C).4,16 These particles appeared to be the viral nucleocapsids. The surfaces of some of these particles were decorated with club shaped projections (arrows, fig 4A). In addition, a ring immediately underneath the envelope was also seen in some of the better preserved particles. This may represent the characteristic helical nucleocapsid of coronaviruses. The cross section of these particles also showed the typical electron lucent centre. Such viral-like particles were not detected in macrophages or other cell types in the lung.

Figure 4.

Ultrastructural features of viral particle containing lung cells. (A) Ultrastructural section from patient 3. Viral-like particles with sizes ranging from 60 to 90 nm were noted within dilated cytoplasmic vesicles. Some of the better preserved structures consistent with viral envelopes are indicated by the arrows. The overall appearance was different from that of multivesicular bodies, which can be seen in some normal cells. Vero cell culture was used for comparison (B and C). (B) Section of an infected Vero cell showing similar features to those seen in the pneumocytes. The viral particles are found within the endoplasmic reticulum (indicated by the asterisk) and on the surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (indicated by the arrows). (C) Typical morphology of coronavirus particles in the supernatant of a Vero cell culture (indicated by the arrows; negative staining with 2% phosphotungstic acid).

DISCUSSION

We have reported the lung pathology of patients with microbiologically confirmed, fatal SARS. These patients were epidemiologically linked to the first index case in Hong Kong, which subsequently resulted in the world endemic of SARS.8–12

The known human coronaviruses, types 229E and OC43, generally cause common cold symptoms and have only rarely been associated with more severe lower respiratory diseases, such as pneumonia in neonates, the elderly, or immunocompromised patients.17–19 However, SARS is a lower respiratory tract disease and upper respiratory tract symptoms are uncommon and mild.8 For all of our patients who died, and in other series,8,20,21 DAD was the dominant picture. DAD is a severe pattern of lung injury and could be secondary to various pulmonary and extrapulmonary insults.22 In addition, the formation of tissue plugs in terminal small airways and alveolar spaces may correlate with the early radiological findings.8,9 Such lesions are not specific to SARS, and may be idiopathic (termed BOOP), or be associated with post-infection states, drug effects, connective tissue diseases, post-organ transplant, and post-irradiation states.23,24 Such BOOP-like lesions in patients with SARS may indicate a non-specific response to lung injury.

“The formation of multinuclear cells is not unique to severe acute respiratory syndrome, and is seen in pneumonia caused by the family of Paramyxoviridae, including parainfluenza viruses, measles, mumps, respiratory syncytial virus and, perhaps, metapneumovirus”

Despite the small numbers of cases, a positive correlation was detected between the duration of illness and the degree of interstitial fibrosis. The results suggested that the pulmonary fibrosis seen in these fatal cases may be related to SARS rather than pre-existing lung lesions. Follow up radiological studies indicated that 62% of surviving patients had pulmonary fibrosis.25 Thus, it is possible that at least in patients with severe SARS, the development of pulmonary fibrosis could be relatively rapid. However, because many patients had severely compromised respiratory function during the illness and required ventilation or oxygen supplementation, the exact role played by each factor in causing pulmonary fibrosis remains speculative.

In our current series, viral culture for coronavirus was positive in postmortem lung tissue in two patients and viral-like particles compatible with coronavirus were demonstrated ultrastructurally in the lung tissue in most of the patients (six of seven patients) These viral-like particles were noted in the pneumocytes, but not in the other cell types within the lung. These observations suggested that the primary target cells for SARS-CoV infection are probably pneumocytes. The atypical morphology of the pneumocytes was probably related to viral cytopathic effects or reactive changes. The presence of multinucleated pneumocytes in SARS has been noted by several other investigators.4,8,20,21 However, the formation of multinuclear cells is not unique to SARS, and is seen in pneumonia caused by the family of Paramyxoviridae, including parainfluenza viruses, measles, mumps, respiratory syncytial virus and, perhaps, metapneumovirus.26 Although foamy histiocytes and multinucleated histiocytes were seen, these probably reflect non-specific secondary changes.27

Apart from lung tissues, postmortem small intestinal tissue was also valuable for viral isolation with a high yield (six of seven patients), suggesting viral intestinal tropism, which may be related to intestinal manifestations in some patients.28 Interestingly, gastrointestinal symptoms were not prominent in our series of patients. For those cases in which SARS-CoV was isolated, the time interval between the patients’ death and necropsy ranged from four to seven days, indicating the presence of viable SARS-CoV up to a week after the patients’ death.

Take home messages.

In severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), coronavirus (CoV) could be isolated from postmortem tissues up to one week after death

Pneumocytes are probably the primary target of infection

Postmortem examination is invaluable because it allows tissue to be sampled for virological investigations and ultrastructural examination

When coupled with the appropriate lung morphological changes, postmortem examination is extremely useful to confirm the diagnosis of SARS-CoV, particularly in clinically unapparent or suspicious but unconfirmed cases

In summary, we have presented the pulmonary pathology in a confirmed and well defined series of fatal SARS cases. The pathological features, in addition to DAD, included the presence of multinucleated pneumocytes and intrabronchial fibrogranulation tissue proliferation (BOOP-like lesions). Although each of these features is non-specific, their combined occurrence, together with positive serological/microbiological investigations and/or ultrastructural tissue examination enables the diagnosis of SARS to be confirmed, and is particularly useful in clinically suspicious cases that do not fulfill the World Health Organisation criteria or in clinically unapparent cases. We have shown that viral particles can be successfully isolated from postmortem lung and small intestinal tissue samples by culture and also by ultrastructural examination, highlighting the importance of necropsy, particularly in those patients who die before the diagnosis is confirmed. At the time of necropsy, when minimal exposure is desirable, a limited dissection with sampling of tissues from the lungs and small intestine may allow for maximal diagnostic yield.

Abbreviations

BOOP, bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia

CMV, cytomegalovirus

CoV, coronavirus

CXR, chest x ray

DAD, diffuse alveolar damage

EM, electron microscopy

HSV, herpes simplex virus

SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Multicountries outbreak update 73, 2003.

- 2.Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003;361:1319–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1967–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1953–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marra MA, Jones SJ, Astell CR, et al. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science 2003;300:1399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS, et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 2003;300:1394–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fouchier RA, Kuiken T, Schutten M, et al. Aetiology: Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature 2003;423:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1986–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong KT, Antonio GE, Hui DS, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: radiographic appearances and pattern of progression in 138 patients. Radiology 2003;228:401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Update: Outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome—worldwide, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, et al. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1977–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B, et al. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med 2003; 15 348:1995–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organisation. Case definition for surveillance of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (http://www.who.int/csr/sars/casedefination/en).

- 14.World Health Organisation. PCR primers for SARS developed by WHO network laboratories (http://www.who.int/csr/sars/primers/en/).

- 15.Chan PKS, Tam JS, Lam CW, et al. Detection of human metapneumovirus from patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a methodological evaluation. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9:1058–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oshiro LS, Schieble JH, Lennette EH. Electron microscopic studies of coronavirus. J Gen Virol 1971;12:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes KV. Coronavirus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields virology, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2001:1187–203.

- 18.El-Sahly HM, Atmar RL, Glezen WP, et al. Spectrum of clinical illness in hospitalized patients with “common cold” virus infections. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fotz RJ, Elkordy MA. Coronavirus pneumonia following autologous bone marrow transplantation for breast cancer. Chest 1999;115:901–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholls JM, Poon LL, Lee KC, et al. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003;361:1773–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding Y, Wang H, Shen H, et al. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a report from China. J Pathol 2003;200:282–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegel MD, Tocina I. Pulmonary edema and the adult respiratory distress syndrome. In: Sperber M, ed. Diffuse lung disorders.. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1998:253–6.

- 23.Epler GR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordier JF. Organising pneumonia. Thorax 2000;55:318–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonio GE, Wong KT, Hill DS, et al. Thin-section CT in patients with severe acute respratory syndrome following hospital discharge: preliminary experience. Radiology 2003;228:810–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Washington C, Winn JR. In: Connor DH, ed. Pathology of infectious diseases. Stamford: Appleton & Lange, 2001:221–7.

- 27.Tse GM, Hui PK, Ma TKF, et al. Sputum cytology of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Clin Pathol 2004;57:256–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung WK, To KF, Chan PK, et al. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1011–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]