Abstract

The traditional approach to oncocytic thyroid lesions classified these as a separate entity, and applied criteria that are somewhat similar to those used for follicular lesions of the thyroid. In general, the guidelines to distinguish hyperplasia from neoplasia, and benign from malignant were crude and unsubstantiated by scientific evidence. In fact, there is no basis to separate oncocytic lesions from other classifications of thyroid pathology. The factors that result in mitochondrial accumulation are largely unrelated to the genetic events that result in proliferation and neoplastic transformation of thyroid follicular epithelial cells. The concept of classifying oncocytic lesions, including follicular variant papillary carcinomas, based on nuclear morphology, immunohistochemical profiles, and molecular markers may pave the way for a better understanding of the biology of oncocytic lesions of the thyroid.

Keywords: immunohistochemistry, molecular diagnostics, oncocytes, thyroid, tumours

The first question that we must ask is “What is oncocytic change?”.

WHAT IS ONCOCYTIC CHANGE

Definition

Oncocytic change is defined as cellular enlargement characterised by an abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm as a result of the accumulation of altered mitochondria.

This is a phenomenon of metaplasia that occurs in inflammatory disorders, such as thyroiditis, or other situations that result in cellular stress.1 The proliferation of oncocytes gives rise to hyperplastic and neoplastic nodules.

Oncocytic tumours are found in the thyroid and other endocrine tissues, including the parathyroid, pituitary, adrenal cortex, pancreas, gut, and lung. Outside of the endocrine system, there is an oncocytic variant of renal cell carcinoma, and salivary glands, particularly the parotid, develop oncocytic nodules and tumours. This discussion will concentrate on thyroid nodules, but many of the principles apply to other sites too.

Oncocytic cells in the thyroid are often called “Hürthle” cells; however, this is a misrepresentation because they were initially described by Askenazy, and the cells that Hürthle described were in fact C cells. Nevertheless, the terminology has been established in most parts of the world (with the exception of Germany where the term “Askenazy cells” has persisted).

Diagnosis

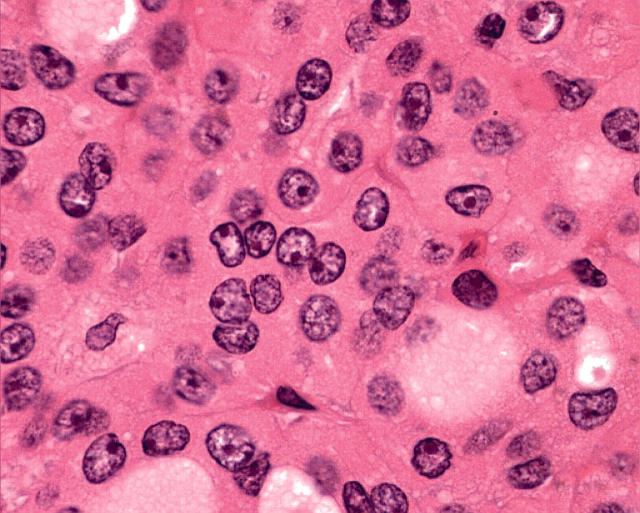

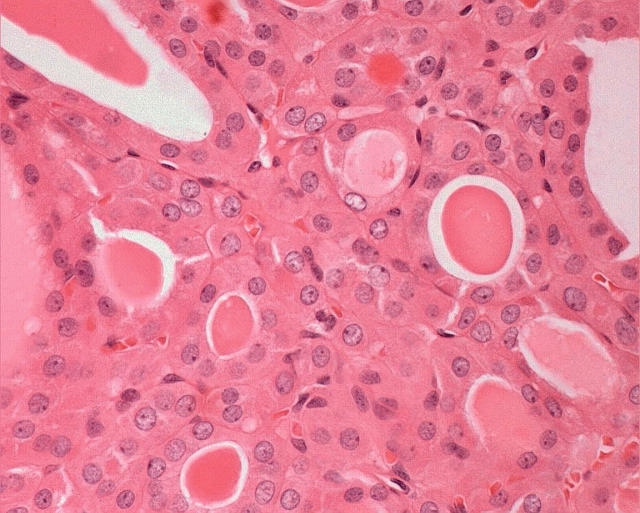

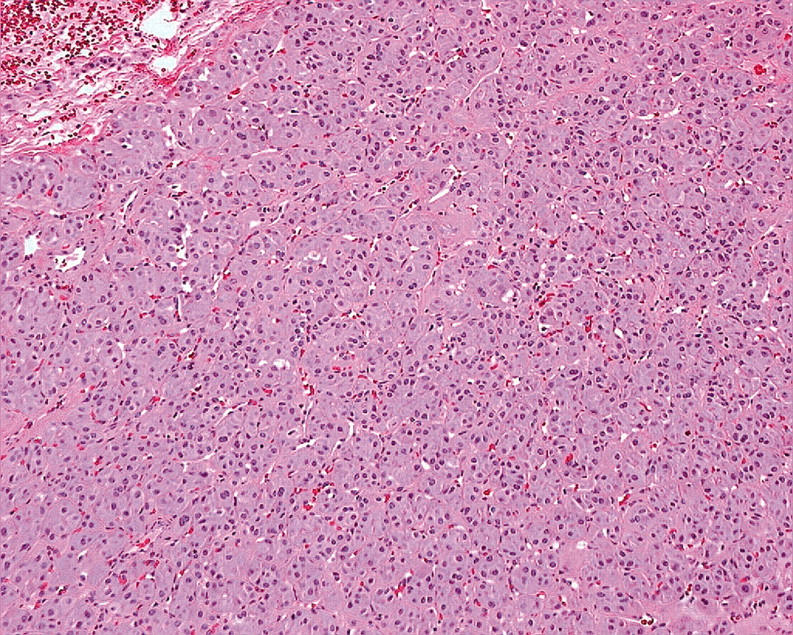

In general, oncocytic change is highly characteristic on conventional haematoxylin and eosin staining. Morphologically, Hürthle cells are characterised by large size, polygonal to square shape, distinct cell borders, voluminous granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a large, often hyperchromatic nucleus with prominent “cherry pink” macronucleoli (fig 1). With the Papanicolau stain, the cytoplasm may be orange, green, or blue. By electron microscopy, the cytoplasmic granularity is produced by large mitochondria filling the cell, consistent with oncocytic transformation.2,3 The diagnosis of an oncocytic tumour is not usually difficult because of these distinctive features, but in borderline or dubious circumstances, mitochondrial markers can be used, including the antimitochondrial antibody 113-1.

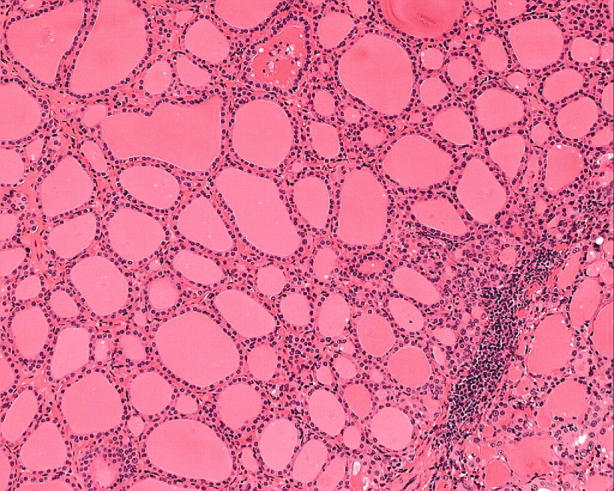

Figure 1.

Oncocytic follicular cells in the thyroid, known as Hürthle cells, are characterised by large size, polygonal to square shape, distinct cell borders, voluminous granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a large, often hyperchromatic nucleus with prominent “cherry pink” macronucleoli.

“The proliferation of oncocytes gives rise to hyperplastic and neoplastic nodules”

In some cases, the degree of oncocytic change precludes recognition of the cell of origin. In this situation, other markers of differentiation can be applied. Immunohistochemistry of these lesions can be confounded by the notorious “stickiness” of oncocytes, which can result in non-specific staining. In addition they have high endogenous peroxidase activity, so that rigorous controls must be performed to enable the results of these studies to be interpreted correctly. Using appropriate technology, one can apply markers such as transcription factors (for example, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1)) to distinguish thyroid from parathyroid oncocytic lesions, enzymes and differentiation proteins (including synaptophysin and chromogranins) to distinguish neuroendocrine tumours, and hormones (such as thyroglobulin, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and other peptide hormones) to characterise endocrine oncocytomas in the thyroid area.

Importance

In some circumstances, oncocytic change is a feature of tumours that have a benign behaviour, such as renal cell carcinomas. Parathyroid tumours with oncocytic change were thought to have reduced functional capacity for hormone production. This has not been substantiated because there are cases of hormone hypersecretion in patients with these lesions,4 and immunohistochemical studies show that these lesions express PTH. In general, however, oncocytic parathyroid tumours tend to be larger than non-oncocytic tumours with similar concentrations of circulating PTH.

In the thyroid, Hürthle cells are found in a variety of conditions and, therefore, are not specific for a particular disease. Individual cells, follicles, or groups of follicles may show Hürthle cell features in irradiated thyroids, in aging thyroids, in nodular goitre, and in chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (fig 2), in addition to that seen in long standing autoimmune hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease). In some of these situations, one can often find an entire nodule composed of oncocytes (fig 3), and the distinction of hyperplasia from neoplasia can be problematic.

Figure 2.

In chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, follicular cells can show extensive oncocytic change, which is most pronounced in areas of inflammation. The nuclei can exhibit crowding, clearing, irregular contours, and grooves, mimicking papillary carcinoma.

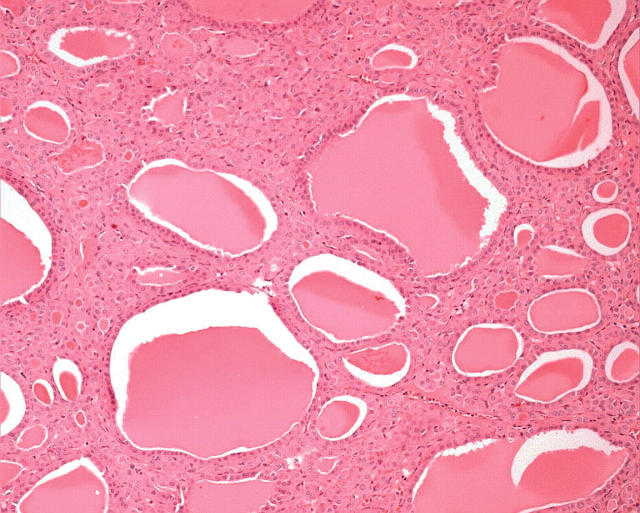

Figure 3.

Nodules of oncocytes in the setting of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (as shown) or in nodular hyperplasia may be hyperplastic or neoplastic. The distinction can be extremely difficult or impossible.

The identification of oncocytic change in thyroid tumours has led to major controversies. Because some lesions that were called benign developed metastases, there were proponents of the view that all oncocytic tumours of the thyroid should be treated as malignancies.5,6 Numerous studies indicated that the criteria that apply to follicular tumours of the thyroid also distinguish malignant from benign Hürthle cell lesions.5,7–13 These included capsular and vascular invasion. Moreover, studies showed that the larger the Hürthle cell lesion, the more likely it is to show invasive characteristics; a Hürthle cell tumour that is 4 cm or greater has an 80% chance of showing histological evidence of malignancy.7 Nuclear atypia, which is the hallmark of the Hürthle cell, multinucleation, and mitotic activity were not considered useful for predicting prognosis. However, there remained a group of Hürthle cell lesions that were not invasive and were considered to be Hürthle cell adenomas, yet they gave rise to lymph node metastases.5 In my opinion, these lesions were a reflection of the failure to recognise oncocytic follicular variant papillary carcinomas.14

Many Hürthle cell tumours, whether benign or malignant, show papillary change, which is really a pseudopapillary phenomenon, because Hürthle cell tumours have only scant stroma and may fall apart during manipulation, fixation, and processing. True oxyphilic or Hürthle cell papillary carcinoma (fig 4) has been reported to comprise from 1% to 11% of all papillary carcinomas.3,15–20 These tumours have a papillary architecture, but are composed predominantly or entirely of Hürthle cells.3,21 The nuclei may exhibit the characteristics of usual papillary carcinoma,16,22 or they may instead resemble the pleomorphic nuclei of Hürthle cells, being large, hyperchromatic, and pleomorphic.17,23 The clinical behaviour of this rare subtype is controversial; some authors have reported that they behave like typical papillary carcinomas,19,21–24 whereas others maintain that the Hürthle cell morphology confers a more aggressive behaviour,25,26 with higher rates of 10 year tumour recurrence and cause specific mortality.17 This suggestion of aggressive behaviour may be attributed to the inclusion of tall cell variant papillary carcinomas in the group of Hürthle cell carcinomas.

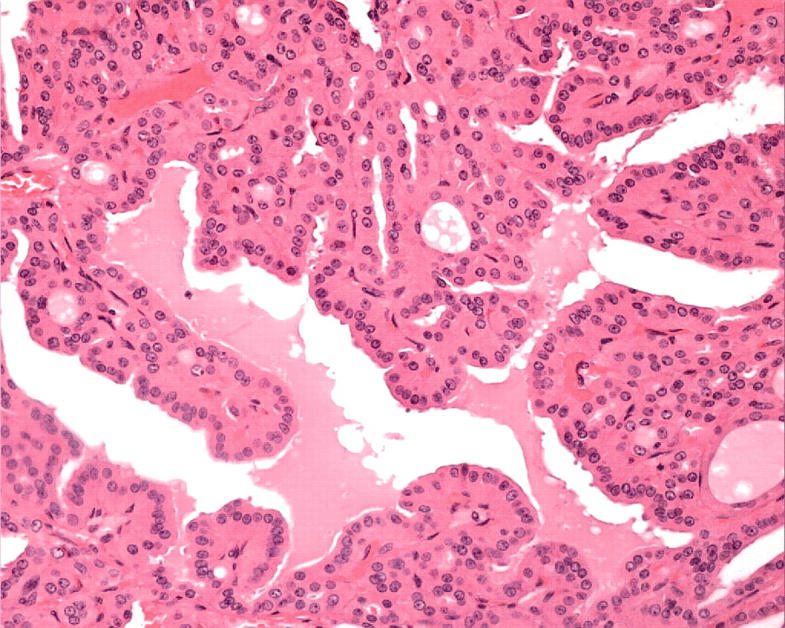

Figure 4.

Oncocytic papillary carcinoma is an accepted diagnosis when the tumour has complex papillary architecture with thin papillae that have true fibrovascular cores, and the papillae are lined predominantly or entirely by Hürthle cells.

“The diagnosis of Hürthle cell follicular variant papillary carcinoma remains controversial”

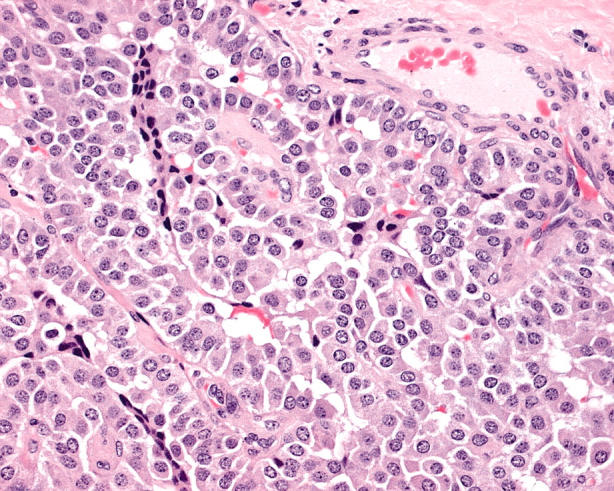

Because of a characteristic cystic change and extensive lymphocytic infiltration into the cores of the papillae of the tumour (fig 5), one morphological subtype of Hürthle cell papillary carcinoma has a striking histological resemblance to papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum of the salivary gland and has been called “Warthin-like tumour of the thyroid”.27 This lesion occurs in the setting of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, predominantly in women, and has a similar prognosis to usual papillary carcinoma.

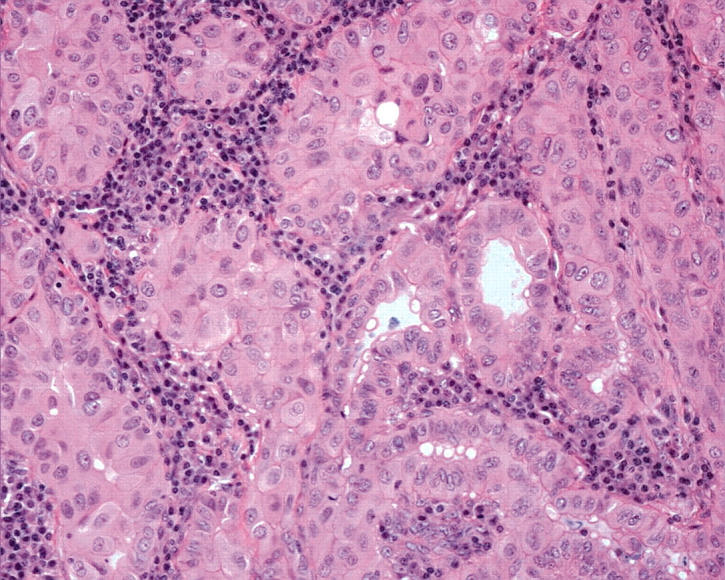

Figure 5.

Some papillary carcinomas composed of oncocytic cells have a pronounced stromal chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. These lesions resemble Warthin’s tumour of the salivary glands and therefore have been called “Warthin-like tumour of the thyroid”. They harbour the characteristic nuclear atypia of papillary carcinoma. Unlike the true Warthin’s tumour, these thyroid neoplasms have malignant potential.

The diagnosis of Hürthle cell follicular variant papillary carcinoma remains controversial. The application of ret/PTC analysis by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) allowed the recognition of a follicular variant of Hürthle cell papillary carcinoma as a group of lesions with no invasive behaviour at the time of diagnosis but which harboured a ret/PTC gene rearrangement.14,28 Many of these lesions exhibit irregularity of architecture, with hypereosinophilic colloid and nuclear features of papillary carcinoma, but these can be obscured by the hyperchromasia and prominent nucleoli of oncocytic change. Nevertheless, they can be recognised when there is a high index of suspicion and with the addition of immunohistochemistry for HBME-1, galectin-3, cytokeratin 19 (CK19), and ret, or by RT-PCR studies of ret rearrangements. These tumours have the potential to metastasise,29 explaining the occurrence of malignancy in patients with a histopathological diagnosis of adenoma.

The management of Hürthle cell carcinoma is controversial.5,11,30–33 In most institutions, patients undergo total thyroidectomy followed by radioactive iodine. Iodine uptake by these lesions tends to be poor.34 External beam radiotherapy is advocated only for locally invasive disease. There is no evidence that oncocytic follicular variant papillary carcinomas behave differently to their non-oncocytic counterparts.29 Some authors have reported that the more aggressive oncocytic carcinomas that behave as follicular carcinomas with widespread metastatic spread have a worse prognosis that do non-oncocytic follicular carcinomas matched for stage and patient parameters; this might be attributable to the reduced capacity for radioactive iodine uptake that these lesions may exhibit.34 The loss of effectiveness of this targeted treatment results in increased morbidity and mortality.

Pathobiology

Hürthle cells have been studied by enzyme histochemistry and have been shown to contain high concentrations of oxidative enzymes.35,36 The pathogenetic basis of oncocytic change is fascinating because mitochondria contain their own separate and parallel DNA. There is a large body of literature that has described and characterised the human mitochondrial genome. Mitochondrial mutations have been identified as the cause of several inherited degenerative disorders.37 Recently, mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms and mutations have been associated with neoplastic disorders.

In much of the literature, the focus has been on mitochondrial DNA alterations that result in preferential survival in hypoxic conditions.38 This work provides an explanation for the malignant behaviour of some tumours that are able to grow in hypoxic conditions and are resistant to conventional treatments. However, much of this work deals with gliomas and cervical carcinomas, where oncocytosis is not a prominent feature, suggesting that the mitochondrial mutations do not result in proliferation.

Mitochondrial mutations have been identified in oncocytic tumours of the thyroid.39,40 These are found in benign and malignant tumours and, therefore, unlike mutations that result in hypoxic survival, do not appear to have prognostic significance. Moreover, similar changes have been found in the non-tumorous thyroid tissue of patients with oncocytic tumours,40 suggesting that certain polymorphisms predispose to this cytological alteration, rather than predisposing to neoplastic alteration.

“Hürthle cells have been studied by enzyme histochemistry and have been shown to contain high concentrations of oxidative enzymes”

Apart from these mitochondrial DNA characteristics, the somatic genetic events underlying oncocytic neoplasms of the thyroid tend to be similar to those in non-oncocytic tumours. Activating ras mutations are infrequent in oncocytic tumours,41 as they are in non-oncocytic differentiated thyroid follicular and papillary carcinomas.42,43 Oncocytic papillary carcinomas harbour ret/PTC gene rearrangements similar to those of non-oncocytic papillary carcinomas.44 The only difference identified to date is frequent chromosomal DNA imbalance, with numerical chromosomal alterations being the dominant feature.41 The importance of these alterations is not known.

Flow cytometric analyses document aneuploid cell populations in 10–25% of Hürthle cell tumours that are clinically and histologically classified as adenomas.45–47 However, once a histological diagnosis of carcinoma is made, aneuploidy on flow cytometry may predict a more aggressive clinical behaviour for that carcinoma.45

THE APPROACH TO THE HÜRTHLE CELL THYROID NODULE

Basic principles

Hürthle cell nodules are diagnosed when more than 75% of a lesion is composed of this cell type. Needle biopsy of Hürthle cell tumours may cause partial or total infarction.48 This probably occurs because of the high metabolic activity of these cells and the delicate blood supply of these lesions, which may readily become inadequate after direct trauma. A solitary tumour of the thyroid occurring in a patient without thyroiditis, which is purely or predominantly composed of Hürthle cells on fine needle aspiration (FNA), should be excised because Hürthle cell tumours show an average 30% malignancy rate based on histology.7

The differential diagnosis of the thyroid nodule includes a large number of lesions, which are listed in fig 6. In the absence of oncocytic change, the criteria used for the diagnosis of each of these lesions is widely accepted, perhaps with the exception of papillary carcinoma, which remains one of the most controversial areas in pathology. The criteria for the diagnosis of lesions that are composed predominantly of Hürthle cells are the same as those applied to follicular lesions that do not contain Hürthle cells.7 Encapsulated lesions with no evidence of capsular or vascular invasion and no nuclear features of papillary carcinoma are diagnosed as Hürthle cell adenomas (fig 7), and those that have penetrated their capsule to invade surrounding tissues are diagnosed as Hürthle cell carcinomas (fig 8). The diagnosis of Hürthle cell papillary carcinoma (see below) is possible when the cytological criteria for papillary carcinoma are present.24

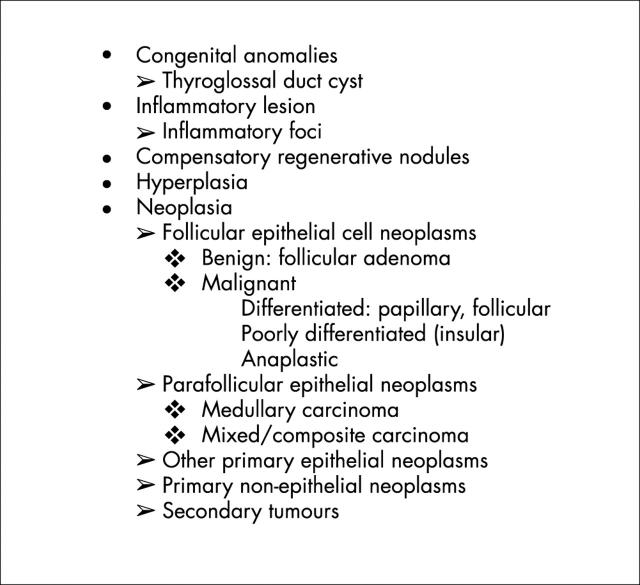

Figure 6.

The differential diagnosis of the thyroid nodule.

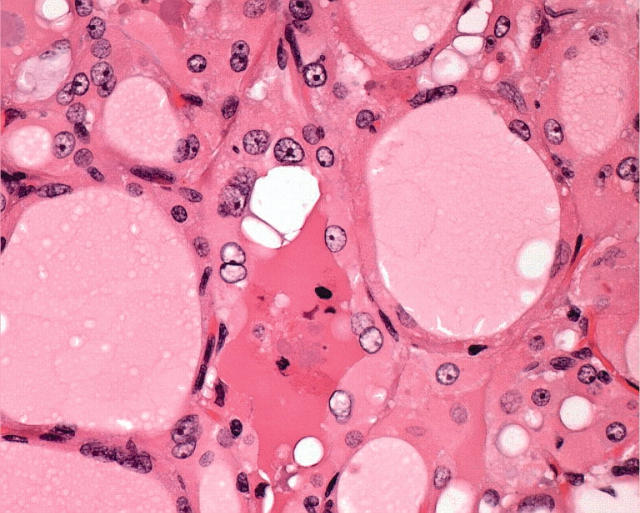

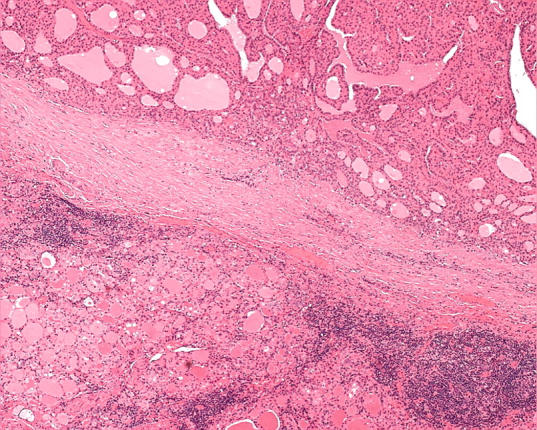

Figure 7.

An oncocytic nodule in the setting of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis may be completely encapsulated and show no evidence of capsular or vascular invasion. In the absence of nuclear features of papillary carcinoma, this would be considered an adenoma.

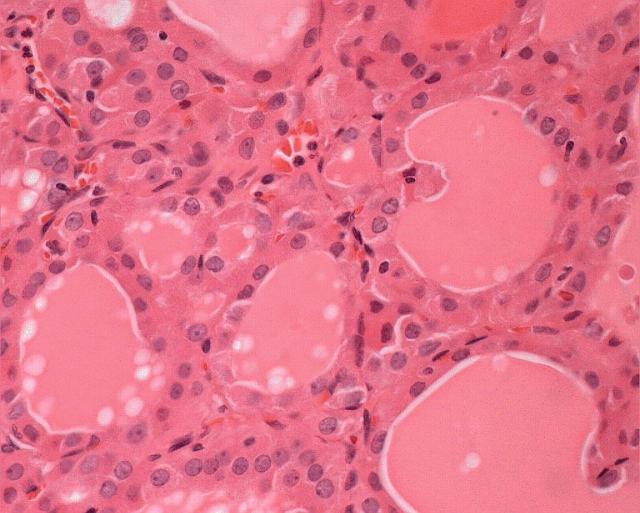

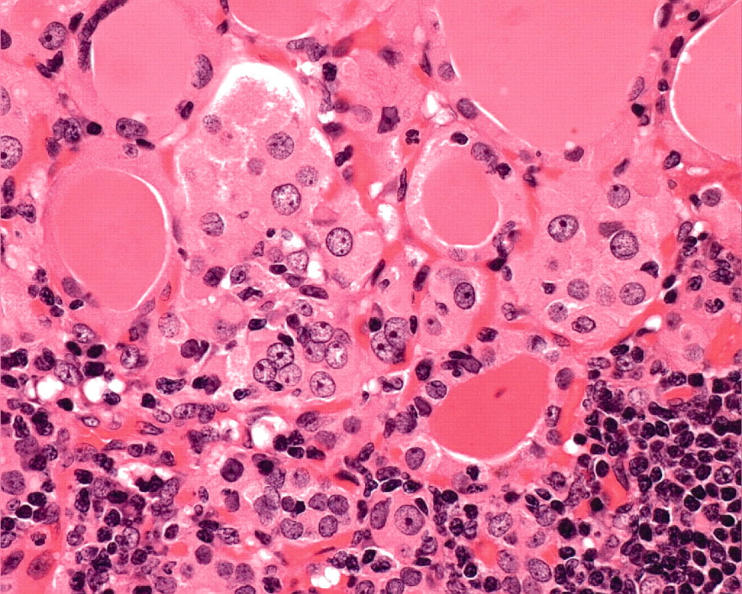

Figure 8.

Solid cellular proliferations of oncocytic thyroid cells that invade surrounding parenchyma are diagnosed as Hürthle cell carcinoma.

As with non-oncocytic lesions, the distinction between hyperplasia and neoplasia can be difficult. In patients with multinodular hyperplasia, dominant nodules are considered by some to be hyperplastic, whereas some pathologists diagnose them as follicular adenomas. Clonality studies have clearly shown that many if not most of the large nodules are indeed monoclonal,49–51 so that the second approach is biologically correct. This changes the approach to the pathobiology of neoplasia because we know (from many other examples in gut, breast, and other sites) that malignant transformation involves a stepwise progression of molecular changes. Therefore, it should not be surprising that malignancy occurs in nodular hyperplasia. The difficulty is in recognising the criteria and the clinical relevance of these changes. In the case of pure follicular proliferations, invasion can be difficult to ascertain in the setting of nodular hyperplasia. In the case of papillary transformation, the threshold for nuclear features is controversial.

If indeed oncocytic change is a metaplastic process, the criteria that apply to oncocytic lesions should be identical to those applied to non-oncocytic lesions. The only possible exception to that argument may be the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma, because the criteria are now accepted to be nuclear, and there may be difficulty identifying nuclear changes of papillary carcinoma in oncocytes that traditionally have large, hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent cherry red nucleoli.

In fact, this is not usually the case. The morphological features identified in papillary carcinoma are usually seen in a large proportion of Hürthle cell papillary carcinomas. The nuclei are enlarged, elongated, irregular in shape, crowded, and overlapping, with prominent grooves and inclusions (fig 9). There is clearing of nucleoplasm and peripheral margination of chromatin (figs 10 and 11). The threshold for these alterations varies among experts. For example, the identification of irregularity of nuclear contours is sufficient for some pathologists (including myself) when it results in a ragged nuclear outline that resembles “crumpled paper” (fig 12). Others require more florid features, such as linear grooves; these are usually present in association with the first finding. Some investigators do not recognise the morphology until the grooves become so pronounced that they fill with cytoplasm and form pseudoinclusions (fig 9).

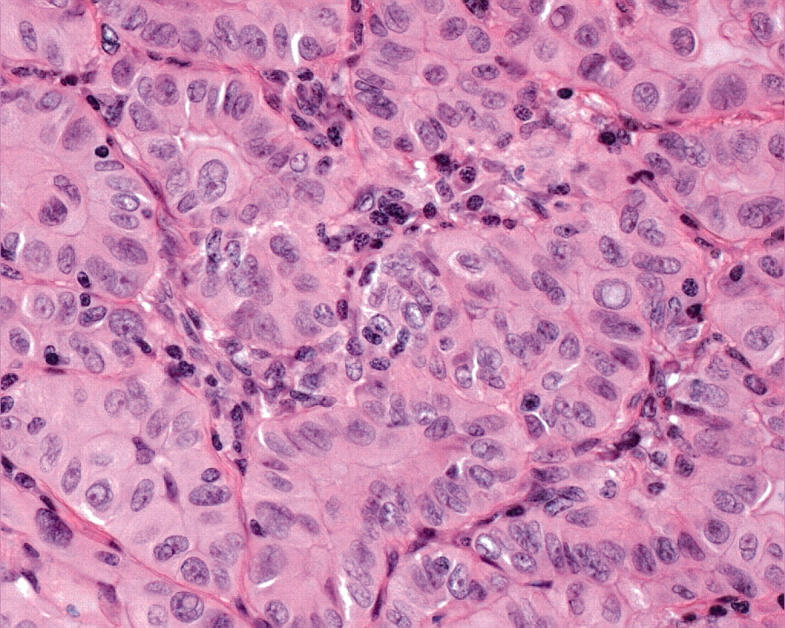

Figure 9.

Hürthle cell papillary carcinoma can be diagnosed in the absence of papillae when the oncocytic cells exhibit the classic nuclear features of papillary carcinoma, namely: nuclear enlargement and elongation, crowding with overlap and moulding, irregular nuclear contours that result in the formation of grooves and, when severe, cytoplasmic pseudoinclusions.

Figure 10.

A Hürthle cell nodule is composed of cells with pronounced clearing of nuclear chromatin; this is a feature of papillary carcinoma.

Figure 11.

The lesion shown in fig 10 is seen at higher magnification to exhibit the nuclear atypia of papillary carcinoma. The nuclei are enlarged, crowded, and overlapping, with irregular nuclear contours and pronounced peripheral margination of chromatin, resulting in optical clearing of the nucleoplasm. Nucleoli are prominent.

Figure 12.

The threshold for the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma is highly variable and controversial. In this case, the nuclei show subtle atypia, including an irregularity of nuclear contour that makes the nuclei resemble “crumpled paper”. There are nuclear indentations and occasional grooves. These features are indicative of the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma and, in this case, the diagnosis was substantiated by immunoreactivity for ret in addition to molecular documentation of a ret/PTC1 gene rearrangement.

“Some investigators do not recognise the morphology until the grooves become so pronounced that they fill with cytoplasm and form pseudoinclusions”

It is the recognition of these nuclear features that has enabled well delineated oncocytic neoplasms that would previously have been called Hürthle cell adenomas to be identified as oncocytic follicular variant papillary carcinomas. The hypothesis has been confirmed by the identification of ret/PTC gene rearrangements, the hallmark of papillary carcinoma, in such lesions.14,28 The recognition of this entity in turn explains the previous publications chastising the pathologist’s diagnosis of Hürthle cell adenoma when the patients went on to develop lymph node metastases.5,6 These data support a new approach to the classification of oncocytic thyroid tumours, as shown in fig 13.

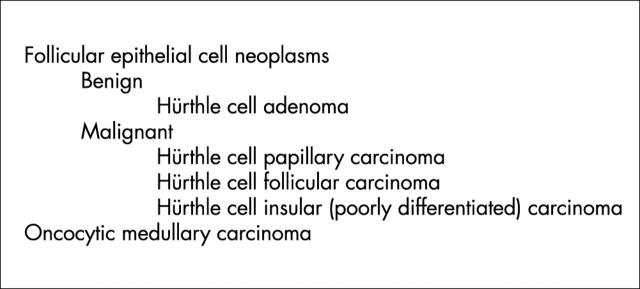

Figure 13.

The classification of oncocytic thyroid neoplasms.

The first step: histopathology

The histopathological architecture of oncocytic carcinomas varies with tumour type. The one unifying feature is the presence of large tumour cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. The nuclei tend to be hyperchromatic and pleomorphic and generally have characteristic large, bright pink nucleoli.52 When colloid is present, there is a tendency for it to be rather basophilic and it may even show calcification.

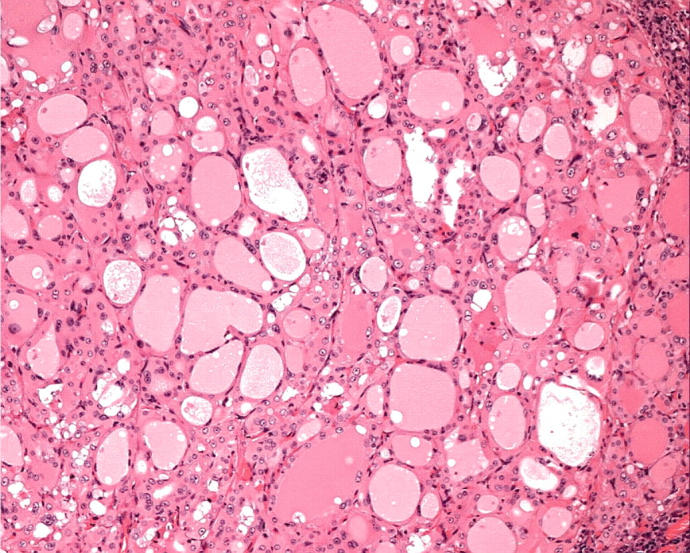

Oncocytic papillary carcinomas may have papillary or follicular architecture. The papillary type are characterised by complex branching papillae in which oncocytic cells cover thin fibrovascular stromal cores (fig 4)3,17,21,22; the “Warthin-like” tumour has intense stromal infiltration by chronic inflammatory cells (fig 5).27 Oncocytic papillary carcinomas with follicular architecture may be macrofollicular or microfollicular with variable colloid storage.14 In this setting, the colloid may be hypereosinophilic (figs 14, 15). They may be well delineated and even encapsulated, but careful evaluation usually identifies at least superficial infiltration of surrounding tissue. Some lesions are frankly and widely invasive.

Figure 14.

A follicular lesion has irregular architecture with variably sized and shaped follicles, hypereosinophilic colloid, and crowded oncocytic cells with nuclear atypia (fig 15).

Figure 15.

The nuclei exhibit subtle features of papillary carcinoma. This tumour exhibited diffuse reactivity for cytokeratin 19 and was found to harbour a ret/PTC3 gene rearrangement, confirming the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma.

The diagnosis of papillary differentiation is based on the nuclear features of these lesions. The oncocytic cells are usually polygonal but may be columnar; they have abundant granular, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei have variably developed atypia of papillary carcinoma, namely: enlargement, oval shape, elongation, and overlap, with clearing, resulting in a ground glass appearance, and irregular nuclear contours with nuclear pseudoinclusions and grooves (figs 9–12). It is important to identify these features in well delineated lesions with follicular architecture, because they may predict lymph node metastasis.

Oncocytic follicular carcinomas have a variety of architectural patterns. They may form follicles that tend to be uniform in size throughout the lesion, and the most common pattern is microfollicular with scant colloid (fig 8). However, most of these lesions have a pattern of solid and/or trabecular growth and are generally devoid of colloid.52 As with other follicular carcinomas, malignancy is based on the identification of invasion that may be minimal, obvious, or widespread. Vascular invasion warrants identification with specific classification as angioinvasive carcinoma. The criteria are not different from those applied to follicular carcinoma.

Oncocytic medullary carcinomas can be difficult to recognise. These lesions usually have a nesting or insular architecture and the cells are polygonal (fig 16) rather than having the spindle shaped morphology of the usual variant.53 The nuclei resemble neuroendocrine nuclei (round to oval with salt and pepper chromatin).

Figure 16.

An oncocytic medullary carcinoma is characterised by polygonal discohesive cells with poorly defined cell borders and relatively bland nuclei, which are round to oval with salt and pepper chromatin. Immunohistochemistry confirms positivity for chromogranin, calcitonin, and carcinoembryonic antigen.

The application of ancillary techniques

If the diagnosis is not obvious on routine histology, immunohistochemistry and molecular diagnostics are helpful tools. If the diagnosis of oncocytic medullary carcinoma is considered, it can be confirmed by identifying chromogranin, calcitonin, and carcinoembryonic antigen immunoreactivity, and lack of thyroglobulin staining in tumour cells.53 Similarly, the possibility of an intrathyroidal or perithyroidal oncocytic parathyroid lesion can be confirmed by the lack of TTF-1 nuclear reactivity and the presence of chromogranin and/or PTH positivity.

“If the diagnosis of oncocytic medullary carcinoma is considered, it can be confirmed by identifying chromogranin, calcitonin, and carcinoembryonic antigen immunoreactivity, and lack of thyroglobulin staining in tumour cells”

If the lesion is clearly of thyroid follicular cell derivation, but malignancy is not unequivocal, there are several useful markers that can be applied. HBME-1, CK19, and ret provide a screen for papillary carcinoma that has been reported to be valuable.54 HBME-1 positivity is seen in more than half of those malignancies of thyroid follicular cell derivation; when positive it is suggestive of malignancy, but when negative, it is not helpful. CK19 is helpful only when there is diffuse positivity throughout the lesion, because strong focal staining is seen in reactive areas around biopsy sites or in degeneration. In my experience, oncocytic thyroid tumours are less often convincingly and strongly positive for this marker than non-oncocytic lesions; however, a diffuse weak signal is common and is difficult to distinguish from non-specific reactivity in oncocytes. Although several authors have recommended the application of galectin-3 immunohistochemistry to identify malignancies of thyroid follicular cell derivation,55–58 we have not had unqualified success with this technique at our institution. Although malignancies may have stronger and more diffuse reactivity for galectin-3, it is also seen in normal thyroid, thyroiditis, and benign follicular proliferations and, therefore, like CK19, must be carefully evaluated and interpreted.

The identification of ret/PTC gene rearrangements has advanced our ability to diagnose papillary carcinoma. Indeed, these genetic alterations have been found to be specific for papillary carcinoma. No other tumour has been reported to harbour ret/PTC rearrangements. They have been reported in some lesions diagnosed as follicular adenomas, but the criteria for establishing that diagnosis are not clear or widely accepted, so that it is possible that those lesions may have been diagnosed as papillary carcinoma by some experts.59,60 Recent data have suggested that glands with Hashimoto’s disease express ret/PTC gene rearrangements.61 In our experience, this is the case when there are nodules of Hürthle cells or micropapillary carcinomas in the tissue submitted for examination, but not if these lesions are carefully excluded from the inflamed tissue examined.62 Stains for ret have been very helpful in recognising the presence of a ret/PTC gene rearrangement,14,54,62 because follicular epithelial cells do not express ret in the absence of a rearrangement. Indeed, some investigators have reported ret expression as the endogenous, non-rearranged receptor in follicular lesions, but it is my opinion that this can be attributed to macrophages, which are usually strongly positive with a membrane staining pattern.

Recently, changes in polyclonal antisera have reduced the usefulness of this immunohistochemical technique to indicate a ret/PTC gene rearrangement. In our laboratory, we have reverted to the use of RT-PCR for ret fusion mRNA62 to determine the presence of gene rearrangements, and this has proved highly valuable to confirm the diagnosis of oncocytic papillary carcinomas. Indeed, this tool can also be applied to fine needle aspiration material if properly fixed, as it is in the alcohol based fixatives that are used for monolayer cytology.63 HBME-1 can also be used as an immunohistochemical marker for application to cytological preparations64,65 but other markers, including CK19 and galectin-3, are not sufficiently specific to be used on cytology specimens.

THE FUTURE APPROACH TO THE DIAGNOSIS OF ONCOCYTIC THYROID TUMOURS

The reality of thyroid histopathology is that the ability to arrive at unequivocal diagnostic criteria is limited. Fortunately, the identification and recognition of aggressive malignancies is relatively easy; oncocytic carcinomas that exhibit vascular invasion, insular, or anaplastic dedifferentiation are readily and consistently diagnosed as aggressive cancers. However, there is a more common scenario of Hürthle cell nodules, often associated with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, that creates a complex diagnostic dilemma for the pathologist.

“Fortunately, the identification and recognition of aggressive malignancies is relatively easy”

Although the microscope remains the first tool in the diagnostic armamentarium, pathologists must recognise the limitations that ensue and search for more accurate, scientific, and objective markers that will allow the accurate classification of hyperplastic lesions, benign neoplasms, and low grade malignancies, which can be safely treated with resection, and higher grade differentiated carcinomas, which require radioactive iodine ablation. Perhaps the future will see the pathologist examining the haematoxylin and eosin slide to determine which array, be it protein, cDNA, or other, should be applied to separate these and other closely related diagnostic entities, to achieve a clinically relevant and valuable diagnostic and prognostic result that will better guide patient management.

Abbreviations

CK, cytokeratin

PTH, parathyroid hormone

RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

TTF-1 thyroid transcription factor 1

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman NB. Cellular involution in thyroid gland: significance of Hürthle cells in myxedema, exhaustion atrophy, Hashimoto’s disease and reaction in irradiation, thiouracil therapy and subtotal resection. J Clin Endocrinol 1949;9:874–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesland JM, Sobrinho-Simoes M, Holm R, et al. Hürthle cell lesions of the thyroid: a combined study using transmission electron microscopy, scanning electron microscopy and immunocytochemistry. Ultrastruct Pathol 1985;8:131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobrinho-Simoes M, Nesland JM, Holm R, et al. Hürthle cell and mitochondrion-rich papillary carcinomas of the thyroid gland: an ultrastructural and immunocytochemical study. Ultrastruct Pathol 1985;8:131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold BM, Kovacs K, Horvath E, et al. Functioning oxyphil cell adenoma of the parathyroid gland: evidence for parathyroid secretory activity of oxyphil cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1974;38:458–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson NW, Dunn EL, Batsakis JG, et al. Hürthle cell lesions of the thyroid gland. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1974;139:555–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant CS, Barr D, Goellner JR, et al. Benign Hürthle cell tumors of the thyroid: a diagnosis to be trusted? World J Surg 1988;12:488–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronner MP, LiVolsi VA. Oxyphilic (Askenasy/Hürthle cell) tumors of the thyroid. Microscopic features predict biologic behavior. Surg Pathol 1988;1:137–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson TL, Lloyd RV, Burney RE, et al. Hürthle cell thyroid tumors: an immunohistochemical study. Cancer 1987;59:107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arganini M, Behar R, Wi TC, et al. Hürthle cell tumors: a twenty-five year experience. Surgery 1986;100:1108–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gosain AK, Clark OH. Hürthle cell neoplasms: malignant potential. Arch Surg 1984;119:515–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Har-El G, Hadar T, Segal K, Levy R, et al. Hurthle cell carcinoma of the thyroid gland. A tumor of moderate malignancy. Cancer 1986;57:1613–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flint A, Lloyd RV. Hürthle cell neoplasms of the thyroid gland. Pathol Annu 1990;25:37–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carcangiu ML, Bianchiu S, Savino D, et al. Follicular Hürthle cell tumors of the thyroid gland. Cancer 1991;68:1944–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung CC, Ezzat S, Ramyar L, et al. Molecular basis of Hurthle cell papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:878–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner LW. Hürthle-cell tumors of the thyroid. Arch Pathol 1955;59:372–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-Campora R, Herrero-Zapatero A, Lerma E, et al. Hürthle cell and mitochondrion-rich cell tumors. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer 1986;57:1154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrera MF, Hay ID, Wu PS, et al. Hürthle cell (oxyphilic) papillary thyroid carcinoma: a variant with more aggressive biologic behavior. World J Surg 1992;16:669–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meissner WA, Adler A. Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. A study of the pathology of two hundred twenty-six cases. Arch Pathol 1958;66:518–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tscholl-Ducommun J, Hedinger C. Papillary thyroid carcinomas. Morphology and prognosis. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat 1982;396:19–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckner ME, Heffess CS, Oertel JE. Oxyphilic papillary thyroid carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1995;103:280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill JH, Werkhaven JA, DeMay RM. Hürthle cell variant of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988;98:338–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berho M, Suster S. The oncocytic variant of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. A clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Hum Pathol 1997;28:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedinger C, Williams ED, Sobin LH. Histological typing of thyroid tumours. World Health Organisation international histological classification of tumours, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1988.

- 24.Chen KTK. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of papillary Hürthle-cell tumors of thyroid: a report of three cases. Diagn Cytopathol 1991;7:53–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbuto D, Carcangiu ML, Rosai J. Papillary Hürthle cell neoplasms of the thyroid gland: a study of 20 cases [abstract]. Lab Invest 1990;62:7A. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu PS-C, Hay ID, Herrmann MA, et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), oxyphilic cell type: a tumor misclassified by the World Health Organization (WHO) [abstract]? Clin Res 1991;39:279A. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Apel RL, Asa SL, LiVolsi VA. Papillary Hürthle cell carcinoma with lymphocytic stroma. “Warthin-like tumor” of the thyroid. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:810–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiappetta G, Toti P, Cetta F, et al. The RET/PTC oncogene is frequently activated in oncocytic thyroid tumors (Hurthle cell adenomas and carcinomas), but not in oncocytic hyperplastic lesions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belchetz G, Cheung CC, Freeman J, et al. Hurthle cell tumors: using molecular techniques to define a novel classification system. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;128:237–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bondeson L, Bondeson A-G, Ljungberg O. Treatment of Hürthle cell neoplasms of the thyroid. Arch Surg 1983;118:1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bondeson L, Bondeson AG, Ljungberg O, et al. Oxyphil tumors of the thyroid. Ann Surg 1981;194:677–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gundry SR, Burney RE, Thompson NW, et al. Total thyroidectomy for Hürthle cell neoplasm of the thyroid. Arch Surg 1983;118:529–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson RG, Brennan MD, Goellner JR, et al. Invasive Hürthle cell carcinoma of the thyroid: natural history and management. Pathol Annu 1984;59:851–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosai J, Carcangiu ML, DeLellis RA. Tumors of the thyroid gland. Atlas of tumor pathology, Third Series, Fascicle 5. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1992.

- 35.Triggs SM, Pearse AGE. Histochemistry of oxidate enzyme systems in the human thyroid with special reference to Askanazy cells. J Pathol Bacteriol 1960;80:353–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark OH, Gerend PL. Thyrotropin receptor-adenylate cyclase system in Hürthle cell neoplasms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1985;39:719–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial diseases in man and mouse. Science 1999;283:1482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subarsky P, Hill RP. The hypoxic tumour microenvironment and metastatic progression. Clin Exp Metastasis 2003;20:237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeh JJ, Lunetta KL, van Orsouw NJ, et al. Somatic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations in papillary thyroid carcinomas and differential mtDNA sequence variants in cases with thyroid tumours. Oncogene 2000;19:2060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maximo V, Soares P, Lima J, et al. Mitochondrial DNA somatic mutations (point mutations and large deletions) and mitochondrial DNA variants in human thyroid pathology: a study with emphasis on Hurthle cell tumors. Am J Pathol 2002;160:1857–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tallini G, Hsueh A, Liu S, et al. Frequent chromosomal DNA unbalance in thyroid oncocytic (Hurthle cell) neoplasms detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Lab Invest 1999;79:547–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ezzat S, Zheng L, Kholenda J, et al. Prevalence of activating ras mutations in morphologically characterized thyroid nodules. Thyroid 1996;6:409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Rostan G, Zhao H, Camp RL, et al. Ras mutations are associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and poor prognosis in thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3226–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tallini G, Asa SL. RET oncogene activation in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol 2001;8:345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLeod MK, Thompson NW, Hudson JL, et al. Flow cytometric measurements of nuclear DNA and ploidy analysis in Hürthle cell neoplasms of the thyroid. Arch Surg 1988;123:849–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan JJ, Hay ID, Grant CS, Rainwater LM, et al. Flow cytometric DNA measurements in benign and malignant Hürthle cell tumors of the thyroid. World J Surg 1988;12:482–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galera-Davidson H, Bobbo M, Bartels PH, et al. Correlation between automated DNA ploidy measurements of Hürthle cell tumors and their histopathologic and clinical features. Anal Quant Cytol Histol 1986;8:158–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kini SR, Miller JM, Abrash MP, et al. Post fine needle aspiration biopsy infarction in thyroid nodules [abstract]. Mod Pathol 1988;1:48A. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Apel RL, Ezzat S, Bapat BV, et al. Clonality of thyroid nodules in sporadic goiter. Diagn Mol Pathol 1995;4:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bamberger AM, Bamberger CM, Barth J, et al. Clonal composition of thyroid nodules from patients with multinodular goiters: determination by X-chromosome inactivation analysis with M27beta [abstract]. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology (Leipzig) 1993;1(suppl):73. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kopp P, Kimura ET, Aeschimann S, et al. Polyclonal and monoclonal thyroid nodules coexist within human multinodular goiters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;79:134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.LiVolsi VA. Surgical pathology of the thyroid, Vol. 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990.

- 53.Chetty R. Hurthle cell medullary carcinomas of the thyroid gland. S Afr J Surg 1990;28:95–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheung CC, Ezzat S, Freeman JL, et al. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2001;14:338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cvejic D, Savin S, Paunovic I, et al. Immuhohistochemical localization of galectin-3 in malignant and benign human thyroid tissue. Anticancer Res 1998;18:2637–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez PL, Merino MJ, Gomez M, et al. Galectin-3 and laminin expression in neoplastic and non-neoplastic thyroid tissue. J Pathol 1997;181:80–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inohara H, Honjo Y, Yoishii T, et al. Expression of galectin-3 in fine-needle aspirates as a diagnostic marker differentiating benign from malignant thyroid neoplasms. Cancer 1999;85:2475–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orlandi F, Saggiorato E, Pivano G, et al. Galectin-3 is a presurgical marker of human thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res 1998;58:3015–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd RV, Erickson LA, Sebo TJ. Diagnosis of follicular variant of papillary carcinoma by a panel of endocrine pathologists [abstract]. Lab Invest 2003;83:106A. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirokawa M, Carney JA, Goellner JR, et al. Observer variation of encapsulated follicular lesions of the thyroid gland. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1508–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wirtschafter A, Schmidt R, Rosen D, et al. Expression of the RET/PTC fusion gene as a marker for papillary carcinoma in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Laryngoscope 1997;107:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugg SL, Ezzat S, Rosen IB, et al. Distinct multiple ret/PTC gene rearrangements in multifocal papillary thyroid neoplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:4116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheung CC, Carydis B, Ezzat S, et al. Analysis of ret/PTC gene rearrangements refines the fine needle aspiration diagnosis of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:2187–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sack MJ, Astengo-Osuna C, Lin BT, et al. HBME-1 immunostaining in thyroid fine-needle aspirations: a useful marker in the diagnosis of carcinoma. Mod Pathol 1997;10:668–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Hoeven KH, Kovatich AJ, Miettinen M. Immunocytochemical evaluation of HBME-1, CA 19-9, and CD-15 (Leu-M1) in fine-needle aspirates of thyroid nodules. Diagn Cytopathol 1997;18:93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]