Abstract

Background: Immunocytochemical accumulation of prion protein (PrP) in lymphoid tissues is a feature of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) that has been used both to aid in the diagnosis of patients and as a basis of large scale screening studies to assess the prevalence of preclinical disease in the UK. However, the specificity of this approach is unknown.

Aim: To assess the specificity of lymphoreticular accumulation of PrP for vCJD by examining a range of human diseases.

Methods: Paraffin wax embedded lymphoreticular tissues from patients with several reactive conditions (58 cases), tumours (27 cases), vCJD (54 cases), and other human prion diseases (56 cases) were assessed. PrP accumulation was assessed by immunocytochemistry using two different monoclonal anti-PrP antibodies and a sensitive detection system.

Results: All cases of vCJD showed widespread lymphoreticular accumulation of PrP; however, this was not seen in the other conditions examined.

Conclusion: Lymphoreticular accumulation of PrP, as assessed by immunocytochemistry, appears to be a highly specific feature of vCJD.

Keywords: variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, prion, immunocytochemistry, specificity, lymphoreticular

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, are fatal neurological disorders characterised by the accumulation of a modified host protein, prion protein (PrP), in the central nervous system. These diseases are transmissible both under natural conditions and experimentally, although the precise nature of the transmissible agent remains unclear. Infectivity is closely associated with an abnormal disease associated isoform of PrP (PrPSc), which is postulated to be the sole component of the infectious agent in the prion hypothesis.1 PrPSc differs from its normal isoform, PrPC, in its increased β sheet content, which renders it relatively resistant to proteolytic degradation, and allows it to accumulate as amyloid plaques in some forms of prion disease, including variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD).1 Human prion diseases occur in three main groups, namely: (1) sporadic CJD; (2) familial diseases including familial CJD disease, fatal familial insomnia, and the Gerstmann–Straussler Scheinker syndrome; and (3) acquired disorders including kuru, iatrogenic CJD, and vCJD. vCJD is the only example of the transmission of a prion disease to humans from another species: there is a large body of evidence to indicate that the transmissible agent in vCJD is identical in its properties to the agent responsible for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE).2,3 This transmission is likely to have occurred by the oral route (consumption of BSE contaminated meat products).

“PrPSc differs from its normal isoform, PrPC, in its increased β sheet content, which renders it relatively resistant to proteolytic degradation”

Experimental models of prion diseases have indicated that oral exposure to a prion agent can result in the spread of infectivity to the central nervous system by two main routes: via the enteric nervous system and the vagus nerve, or following replication of the agent in lymphoid tissues.4 Lymphoreticular accumulation of PrPSc is a feature of several animal prion disorders and appears to be a consistent feature of vCJD.5–7 Animal models suggest that PrPSc accumulates in lymphoreticular tissues early on in the disease process,8 reliably predicting future neurological disease,9,10 and the accumulation of PrPSc has been used to diagnose preclinical scrapie, with an estimated sensitivity and specificity of greater than 90%.10 The lymphoreticular accumulation of PrPSc in the preclinical phase of vCJD,11 together with the availability of large tissue archives of surgically removed human tissue, has allowed national screening of appendix and tonsil samples to look for PrPSc accumulation as an estimate of the number of individuals who may be incubating vCJD in the UK.12 In the absence of a blood based test for vCJD, such estimates are the only means of determining the potential risk of iatrogenic spread of vCJD via blood products, organ transplants, or surgical instruments.12 Anti-PrP antibodies that can distinguish PrPC from PrPSc would be extremely useful in this regard. Two groups have reported the development of PrPSc specific antibodies, but these are not yet commercially available, and their selective reactivity appears to be restricted to interactions with native PrP, thus limiting their application to techniques such as immunoprecipitation followed by western blotting.13,14 Ethical constraints require screening studies to be carried out in an anonymised manner,12 so that positive cases cannot be identified to determine whether they develop vCJD.

Although the absence of lymphoreticular accumulation of PrP has been previously demonstrated in postmortem tissues from a range of neurological disorders,6 a systematic study of its specificity has not been published. To assess further the specificity of lymphoreticular PrP accumulation for vCJD we have investigated a range of reactive and neoplastic conditions, most of which are known to be associated with prominent follicular dendritic cell networks, in addition to human prion disorders, using identical immunocytochemical techniques to those used in the screening studies.15,16

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue samples

Archival paraffin wax embedded tissue samples from a range of reactive and neoplastic conditions involving lymphoreticular tissue were retrieved from the archives of the pathology departments in Plymouth, UK and Pittsburgh, USA. All such cases from the UK were pre-1986, to ensure that the individuals had not been exposed to BSE contaminated food products. In total, 58 reactive lymph nodes were assessed, which included cases of probable tuberculosis, sarcoid, toxoplasmosis, and cat scratch disease. Thirteen cases of human immunodeficiency virus infection were examined; these were all serologically confirmed and consisted of seven surgically removed tonsils and lymph nodes and six postmortem lymph nodes and spleens, including one case with additional cytomegalovirus infection. A range of 21 lymphomas and six carcinomas, metastatic to lymph nodes, was also examined. All cases were reviewed, and lymphomas were classified using current World Health Organisation guidelines.17 In addition, paraffin wax embedded samples of spleen and other lymphoid tissues obtained after necropsy were studied in 54 cases of vCJD, 53 cases of sporadic CJD, and three cases of familial prion disease from the archives of the National CJD Surveillance Unit in Edinburgh, UK, some of which had also been assessed by western blot examination for PrPSc.5 Table 1 provides a summary of non-vCJD case details. Samples were anonymised before analysis. Local ethical committee approval was obtained for this work.

Table 1.

Conditions other than variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) assessed

| Conditions | Number |

| Reactive conditions | |

| Non-specific lymphoid hyperplasia | 26 |

| Non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation | 6 |

| Necrotising granulomatous inflammation | 9 |

| Toxoplasmosis pattern | 2 |

| Cat-scratch pattern | 1 |

| Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy | 1 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | 13 |

| Tumours | |

| Classic Hodgkin lymphoma | 8 |

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | 8 |

| Follicular lymphoma | 1 |

| Small lymphocytic lymphoma | 1 |

| Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma | 3 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 |

| Carcinoma not otherwise specified | 3 |

| Prion disease | |

| Sporadic CJD | 53 |

| Familial CJD | 3 |

| Total | 141 |

Immunocytochemistry

Sections (4 μm thick) were cut from paraffin wax tissue blocks. Sections were pretreated by autoclaving at 121°C for 10 minutes, followed by immersion in 96% formic acid for five minutes and digestion with proteinase K (10 μg/ml) for five minutes at room temperature, to enhance PrPSc detection and reduce PrPc detection. PrP was detected with the monoclonal antibodies 3F4 (Dako, Ely, Cambridgeshire, UK) and KG9 (IAH, TSE Resource Centre, Newbury, Berkshire, UK), and visualised using the CSA amplification system (Dako), which gives superior results in terms of sensitivity to most other immunohistochemical detection systems.18 Postmortem tonsil tissues from confirmed cases of vCJD were used as a positive control for each group of slides stained by immunocytochemistry for PrP. Western blot analysis for protease resistant PrP was performed in cases of vCJD and sporadic CJD where frozen samples of lymphoid tissues were available, according to a previously published protocol.19 Tissues from known patients with CJD were handled in accordance with Department of Health guidance, which allow for derogation from category 3 containment (www.doh.gov.uk/cjd/tseguidance).

RESULTS

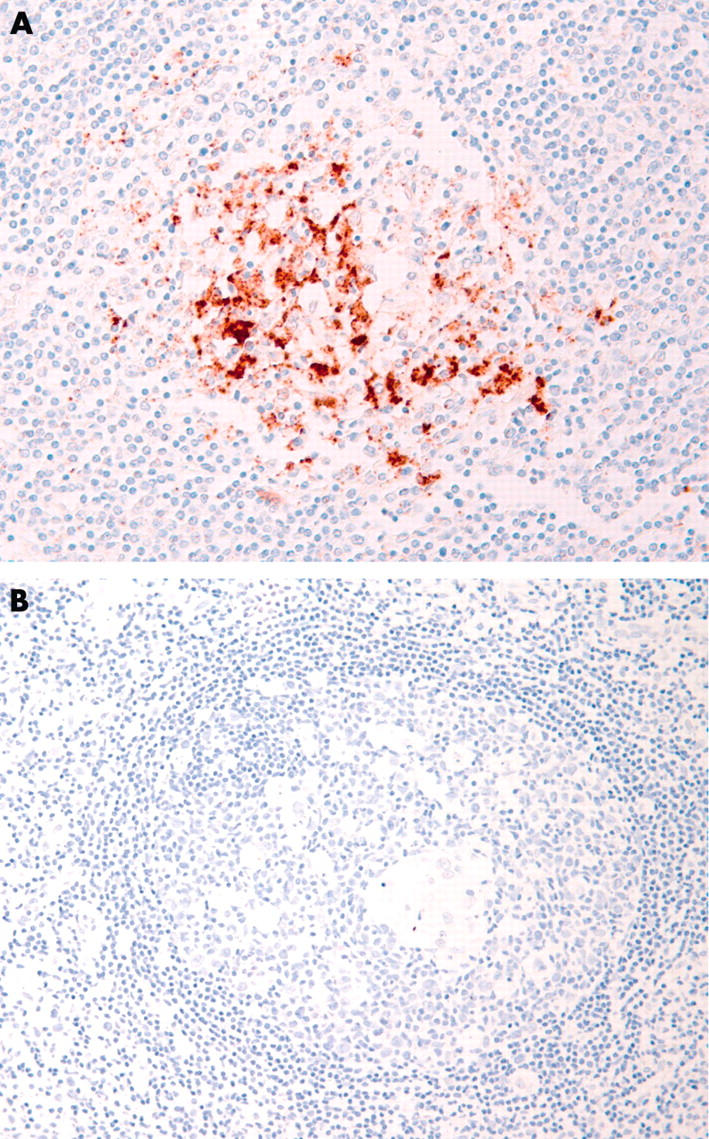

All cases of vCJD showed lymphoreticular PrP accumulation by immunocytochemistry with both anti-PrP antibodies in follicular dendritic cells and macrophages (fig 1A). In the nine cases assessed by western blot analysis, all showed detectable protease resistant PrPSc in one or more of the lymphoreticular tissues that were available for assay.

Figure 1.

(A) Postmortem tonsil from a case of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease showing prominent granular immunoreactivity in follicular dendritic cells and macrophages, following immunocytochemistry with the monoclonal anti-prion protein (PrP) antibody KG9. (B) Reactive lymphoid follicle from a case of cat scratch disease, showing an absence of PrP immunoreactivity.

Of the remaining non-vCJD cases, all were negative with both anti-PrP antibodies by immunocytochemistry (fig 1B). Seven of the sporadic CJD cases were also examined by western blotting and these too proved uniformly negative for the available lymphoreticular tissues. The presence of follicular dendritic cells was confirmed by the identification of secondary lymphoid follicles or CD21 immunoreactive cells in all except seven cases (one case of granulomatous inflammation, four cases of diffuse large B cell lymphoma, and two cases of metastatic carcinoma).

Take home messages.

Lymphoreticular accumulation of prion protein (PrP), as assessed by immunocytochemistry, appears to be a highly specific feature of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD)

PrP was not found in the other tissues tested: a variety of reactive conditions and tumours involving lymphoreticular tissue, and other human prion diseases

DISCUSSION

We have confirmed previous observations that lymphoreticular PrPSc accumulation is a consistent and widespread finding in vCJD,5,6 occurring in tonsils, spleen, lymph nodes, appendix, and ileum. None of the 56 cases of familial and sporadic CJD showed lymphoreticular PrPSc accumulation, in keeping with two previous studies that investigated a total of 35 prion disorders, including sporadic CJD, iatrogenic CJD, and familial prion disease, all of which were negative.6,20 Therefore, these findings suggest that lymphoreticular PrPSc accumulation is a specific feature of vCJD in human prion diseases; the reasons for this are unclear. It is possible that a combination of factors such as the strain type,2 oral exposure, and crossing the species barrier predispose to lymphoreticular PrPSc accumulation in humans (although it does not appear to be a consistent feature of BSE related diseases in other species21).

“The absence of positive cases indicates that PrPC does not accumulate in lymphoid tissues as a “non-specific” reaction to immunological stimulation (as it may do in the brain after oxidative cell stress)”

Screening studies for preclinical scrapie9,10 and vCJD15,16 have used immunocytochemistry to demonstrate lymphoreticular PrPSc accumulation. Although published data indicate that the PrP immunoreactivity in lymphoreticular tissues in vCJD represents protease resistant PrPSc,6,7 and is transmissible,22 the specificity of immunocytochemistry in the context of large scale screening studies of human tissue samples is unclear. None of the currently commercially available antibodies can reliably differentiate PrPC from PrPSc, so it is possible that they could also detect PrPC accumulation in non-prion disorders, resulting in a “false positive”.15 In addition, immunocytochemical accumulation of PrP in tonsil, and other lymphoid tissues, has been used as an aid to diagnose vCJD during life and at necropsy.6 Therefore, we have systematically examined a range of reactive and neoplastic non-prion disorders for evidence of PrPC accumulation in lymphoid tissues. These samples were chosen because the positive sample in our screening study showed PrP accumulation within follicular dendritic cells in secondary follicles,15 and we wanted to examine the possibility that a reactive condition could cause upregulation of PrPc in these cells by examining a wide range of conditions that are known to be associated with prominent follicular dendritic cell networks. The absence of positive cases indicates that PrPC does not accumulate in lymphoid tissues as a “non-specific” reaction to immunological stimulation (as it may do in the brain after oxidative cell stress23,24). It is clearly impossible to look for PrPC accumulation in all diseases, and although our study has only investigated a relatively small number of conditions, the findings suggest that lymphoreticular accumulation of PrP is a specific feature of vCJD.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored in part by a Department of Health grant held by DAH. The National CJD Surveillance Unit is funded by the Department of Health and the Scottish Executive Department of Health. The support of all neuropathologists in the UK is gratefully acknowledged; the unit is a member of the EU funded PRIONET Concerted Action (QLK2-CT-2000-00837). We are grateful to S Lowrie, R Baugh, M LeGrice, and M Moore for expert technical support.

Abbreviations

BSE, bovine spongiform encephalopathy

CJD, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

PrP, prion protein

vCJD, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

REFERENCES

- 1.Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:13363–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruce ME, Will RG, Ironside JW, et al. Transmissions to mice indicate that “new variant” CJD is caused by the BSE agent. Nature 1997;389:498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collinge J, Sidle KC, Meads J, et al. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of “new variant” CJD. Nature 1996;383:685–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beekes M, McBride PA. Early accumulation of pathological PrP in the enteric nervous system and gut-associated lymphoid tissue of hamsters orally infected with scrapie. Neurosci Lett 2000;278:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ironside JW, McCardle L, Horsburgh A, et al. Pathological diagnosis of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. APMIS 2002;110:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill AF, Butterworth RJ, Joiner S, et al. Investigation of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and other human prion diseases with tonsil biopsy samples. Lancet 1999;353:183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadsworth JD, Joiner S, Hill AF, et al. Tissue distribution of protease resistant prion protein in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease using a highly sensitive immunoblotting assay. Lancet 2001;358:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eklund CM, Kennedy RC, Hadlow WJ. Pathogenesis of scrapie virus infection in the mouse. J Infect Dis 1967;117:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreuder BE, van Keulen LJ, Vromans ME, et al. Tonsillar biopsy and PrPSc detection in the preclinical diagnosis of scrapie. Vet Rec 1998;142:564–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Rourke KI, Baszler TV, Besser TE, et al. Preclinical diagnosis of scrapie by immunohistochemistry of third eyelid lymphoid tissue. J Clin Microbiol 2000;38:3254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilton DA, Fathers E, Edwards P, et al. Prion immunoreactivity in appendix before clinical onset of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Lancet 1998;352:703–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilton DA. vCJD—predicting the future? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2000;26:405–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korth C, Stierli B, Streit P, et al. Prion (PrPSc)-specific epitope defined by a monoclonal antibody. Nature 1997;390:74–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paramithiotis E, Pinard M, Lawton T, et al. A prion protein epitope selective for the pathologically misfolded conformation. Nat Med 2003;9:893–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilton DA, Ghani AC, Conyers L, et al. Accumulation of prion protein in tonsil and appendix: review of tissue samples. BMJ 2002;325:633–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ironside JW, Hilton DA, Ghani A, et al. Retrospective study of prion-protein accumulation in tonsil and appendix tissues. Lancet 2000;355:1693–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. Pathology and genetics of tumours of haemopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press, 2001.

- 18.Sabattini E, Bisgaard K, Ascani S, et al. The EnVision++ system: a new immunohistochemical method for diagnostics and research. Critical comparison with the APAAP, ChemMate, CSA, LABC, and SABC techniques. J Clin Pathol 1998;51:506–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ironside JW, Head MW, Bell JE, et al. Laboratory diagnosis of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Histopathology 2000;37:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawashima T, Furukawa H, Doh-Ura K, et al. Diagnosis of new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease by tonsil biopsy. Lancet 1997;350:68–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryder SJ, Wells GA, Bradshaw JM, et al. Inconsistent detection of PrP in extraneural tissues of cats with feline spongiform encephalopathy. Vet Rec 2001;148:437–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce ME, McConnell I, Will RG, et al. Detection of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease infectivity in extraneural tissues. Lancet 2001;358:208–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillier CE, Salmon RL, Neal JW, et al. Possible underascertainment of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a systematic study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:304–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esiri MM, Carter J, Ironside JW. Prion protein immunoreactivity in brain samples from an unselected autopsy population: findings in 200 consecutive cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2000;26:273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]