Abstract

Background: Steatosis is present on liver biopsy in approximately 50% of patients with hepatitis C; its association with stage of fibrosis has been reported, but its relation to other fibrosis associated factors is unknown.

Aim: To study the relation between steatosis and other histological features in patients with hepatitis C, and changes in steatosis with time.

Methods: Cross sectional study: 233 routine liver biopsies from 219 patients with hepatitis C; hepatectomy specimens from 65 patients transplanted for hepatitis C cirrhosis. Longitudinal study: 41 patients with two biopsies and 10 patients with three biopsies performed over 2–8 years. Biopsies were scored by the Ishak scheme, and degree of steatosis assessed subjectively. Multivariate analysis was used to study the interaction of fibrosis associated factors. Changes in steatosis over time in individual patients were explored in the longitudinal study.

Results: Steatosis was present in 50% of biopsies. It correlated strongly with fibrosis in non-cirrhotic samples, but declined in cirrhosis, and was unusual in transplant hepatectomy specimens. On multivariate analysis of non-cirrhotic biopsies, steatosis was associated with increasing patient age and remained significantly associated with fibrosis independent of portal inflammation and interface hepatitis. In the longitudinal study, steatosis persisted and increased over time, except in patients developing cirrhosis.

Conclusions: Steatosis is associated with fibrosis independently of necroinflammation, but declines in cirrhosis. It may represent a pathogenic pathway distinct from necroinflammatory activity in the generation of liver fibrosis, and should be included in the assessment of biopsies for clinical and research purposes.

Keywords: hepatitis C, steatosis, fibrosis

Since the discovery of hepatitis C, there have been several investigations of the role of biopsy histology in determining the severity of chronic hepatitis and progression of disease.1–5 Most of these studies used histological scoring systems for chronic hepatitis that did not include the assessment of steatosis. The extent of fibrosis and architectural disturbance (stage of disease) increases with time, but at a rate that varies widely between individuals, with some progressing to cirrhosis within 10 years of viral acquisition, and others showing only mild fibrosis after 30 years.4 Clinical factors associated with increasing fibrosis include older age at viral acquisition, male sex, alcohol consumption, and co-infection with hepatitis B virus or human immunodeficiency virus.6

Steatosis is seen in 30–70% of liver biopsies from patients with chronic hepatitis C,7,8 more frequently than is seen in other causes of chronic hepatitis,9 and in a high proportion of patients no other cause of fatty liver (such as high alcohol intake or high body mass index (BMI)) can be identified.10,11 Steatosis is thought to be a specific cytopathic effect of the hepatitis C virus (HCV),12 and may be particularly associated with the type 3 genotype.7,10

Some studies have shown an association between steatosis and the stage of fibrosis on liver biopsy,7,8,13–17 but others have not.3,10 If such an association exists, this suggests that steatosis may be a factor predicting increased risk of progression of fibrosis; alternatively, steatosis could be acquired during the progression of chronic hepatitis C.

“Steatosis is thought to be a specific cytopathic effect of the hepatitis C virus, and may be particularly associated with the type 3 genotype”

To date, there have been no reports describing changes in the degree of steatosis in patients having repeat biopsies. It was our impression that, although steatosis was associated with increasing fibrosis in liver biopsies from our patients with hepatitis C, it was rarely present in transplant hepatectomy specimens. Our aim in this study was to explore the relation between steatosis, fibrosis, and other histological features in a series of biopsies from patients with hepatitis C, and to determine the frequency of steatosis in hepatectomy specimens in patients undergoing liver transplantation for hepatitis C. In the subgroup of patients with more than one biopsy, we examined whether steatosis was transient or sustained in individual patients.

METHOD

Cross sectional study

We studied liver biopsies from patients with chronic hepatitis C who were polymerase chain reaction positive for HCV RNA biopsied at our institution between 1997 and 2001 (group 1). There were 233 adequate liver biopsies (> 1 cm, > 4 portal tracts) from 219 patients: the patients were aged between 17 and 68, with a mean age of 37.9 years; 138 were male and 81 were female. Biopsies were routinely processed; 3 µm thick sections were then stained for reticulin and using haematoxylin and eosin, van Gieson, and periodic acid Schiff ±diastase. The slides were scored prospectively by one pathologist (JIW) using the Ishak scheme. Fatty change was estimated subjectively and scored as absent (0), or present in < 30% hepatocytes (1+), 30–60% hepatocytes (2+), or > 60% hepatocytes (3+).

Slides from 65 hepatectomy specimens from patients receiving a liver transplant for cirrhosis caused by hepatitis C were also reviewed, and the presence and extent of steatosis recorded (group 2).

Longitudinal study

Fifty one patients who had undergone more than one biopsy (41 with two biopsies and 10 with three biopsies) were identified from departmental records (group 3); these included 14 patients from whom both biopsies were included in group 1, and 37 patients whose previous biopsy was between 1991 and 1997. The time between the first and last biopsies was from one to eight years (mean, 3.33). The following clinical details were collected from these patients’ notes: estimated year and likely route of exposure to hepatitis C, alcohol consumption, weight, hepatitis B status, mean and peak alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations, and details of treatment for hepatitis C.

Slides from these biopsies were retrieved from the departmental file, and the steatosis was reassessed by one pathologist (JIW), blinded to the patient’s identity. The degree of steatosis was scored as 0–3, as above, and the nature of the steatosis (macrovesicular, microvesicular, or mixed) and any features of steatohepatitis—Mallory bodies, ballooning of hepatocytes, and/or zone 3 pericellular collagen deposition—were recorded. In addition, to investigate the importance of mild degrees of steatosis, the biopsies showing grade 1 steatosis were re-scored into three groups: those showing steatosis in < 1–2%, 3–10%, and 11–30% of hepatocytes.

Statistics

Spearman correlation was used to test the association between age, disease stage, and steatosis. Individual associations between steatosis and inflammatory grade, and the comparison of steatosis in paired biopsies was by the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate analysis for the factors associated with steatosis and fibrosis was done using the General Linear Model. Statistical package Stata7.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for all the data analysis.

RESULTS

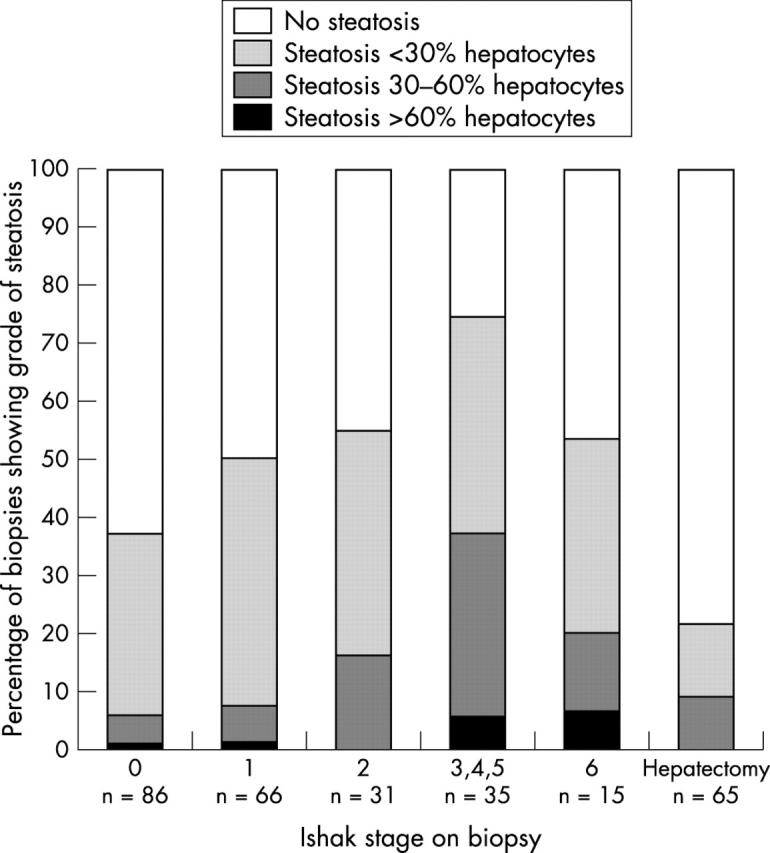

Steatosis was present in 117 of 233 (50.2%) biopsies from group 1 patients, whereas fibrosis was found in 148 of 233 (63.5%). There was a significant association between the score for steatosis and the stage of fibrosis on biopsy (Spearman’s ρ, 0.2903; p < 0.01; table 1; fig 1).

Table 1.

Degree of steatosis and stage of fibrosis in 233 liver biopsies and in hepatectomy specimens from 65 transplant patients

| Steatosis score | Stage of fibrosis on biopsy | Total biopsies | Transplant hepatectomy | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| 0 | 54 | 33 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 117 | 51 |

| 1 | 27 | 28 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 85 | 8 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 26 | 6 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Total | 86 | 66 | 31 | 19 | 4 | 12 | 15 | 233 | 65 |

Figure 1.

Proportion of biopsies with steatosis according to stage of fibrosis in 233 liver biopsies and 65 hepatectomy specimens from patients with hepatitis C.

The proportion of patients with steatosis in their liver biopsy was lower in those with cirrhosis (eight of 15) than those with stage 3–5 fibrosis (26 of 35), although this was not significant. When biopsies showing cirrhosis were excluded, the association between steatosis and fibrosis became stronger (p < 0.0001). Fifty one of the 65 cirrhotic livers from the patients transplanted for hepatitis C (group 2) showed no steatosis, and when steatosis was present, it was seen in some nodules rather than diffusely, and was generally mild. Steatosis was present significantly less often at the time of transplantation than in needle biopsies from patients found to have cirrhotic livers on biopsy (p = 0.03)

Because steatosis showed a positive association with stage of fibrosis in biopsies from non-cirrhotic livers, but declined in patients with cirrhosis, we excluded biopsies from patients with cirrhosis in our statistical analysis of factors associated with fibrosis and steatosis.

Steatosis and fibrosis in patients without cirrhosis

By univariate analysis, steatosis showed a significant association with increasing patient age (p < 0.0001). It was seen more frequently in men, but this association was not significant (p = 0.067). In addition to the association between steatosis and stage of fibrosis (p < 0.0001), we found a significant association between steatosis and interface hepatitis (p = 0.005) and portal inflammation (p = 0.001), but not with lobular activity (p = 0.374).

Fibrosis was significantly more common in men than in women (p = 0.005) and there was a significant association between stage of fibrosis and increasing patient age (p < 0.0001). All three components of the necroinflammatory score showed a significant association with fibrosis (interface hepatitis, p < 0.0001; portal inflammation, p < 0.0001; and lobular necroinflammation, p = 0.0004).

Multivariate analysis

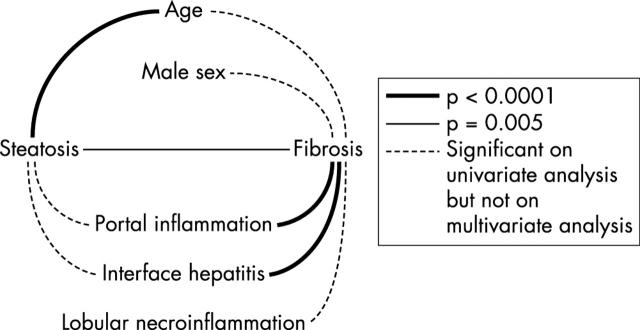

We found that the association between steatosis and fibrosis remained significant in the multivariate model when age, sex, and necroinflammatory activity were considered (p = 0.005). In single factor correlation analysis, we found that both steatosis and fibrosis were significantly associated with age (p < 0.0001 for both, Spearman test). However, in the multivariate model, the correlation between steatosis and age still existed (p < 0.0001), whereas the correlation between fibrosis and age disappeared when steatosis and the necroinflammatory activity factors were taken into account (p = 0.159); fig 2 shows the statistical associations between these factors.

Figure 2.

Association of steatosis and other factors with fibrosis on multivariate analysis.

The factors that were significantly associated with fibrosis in the multivariate model were steatosis (p = 0.005), portal inflammation, and interface hepatitis. Once fibrosis was added into the multivariate model the associations of portal inflammation and interface hepatitis with steatosis disappeared, indicating that the univariate association with steatosis is because each factor is separately linked to fibrosis. The univariate associations of male sex (p = 0.005) and lobular necroinflammation (p = 0.0004) with fibrosis did not remain significant in the multivariate model.

Patients with follow up biopsies

The presence or absence of steatosis was concordant between first and last biopsies in 38 of the 51 patients with follow up biopsies (group 3). There was a strong positive association between steatosis score in the first biopsy and second biopsy (p < 0.001). Steatosis was both macrovesicular and microvesicular in most biopsies, and none showed convincing evidence of steatohepatitis.

Table 2 shows the degree of steatosis in first and final biopsies for group 3 patients. The degree of steatosis increased between the first and the last biopsy in 18 patients, decreased in eight patients, and was unchanged in 25 patients. In most patients acquiring steatosis, this was very mild (affecting 1–2% hepatocytes in six of nine patients), whereas this degree of steatosis persisted or increased in five of seven patients who had 1–2% steatosis on initial biopsy, suggesting that steatosis is initially very mild and increases gradually over time.

Table 2.

Degree of steatosis in first and last biopsy for 51 patients in group 3

| Steatosis in first biopsy | Steatosis in second biopsy | ||||

| None | 1–2% | 3–10% | 11–30% | >30% | |

| None | 15 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 1–2% | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 3–10% | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 11–30% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| >30% | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

Twenty two patients were treated for hepatitis C in the time between taking these biopsies; although overall there was no clear relation between treatment and changes in steatosis, five of eight patients with less steatosis on repeat biopsy had been treated (regardless of viral response) compared with 17 of 43 with unchanged or increased steatosis. The fibrosis score increased in 15 patients, decreased in 11 patients, and was unchanged in 25 patients; in this small group, there was no clear relation between the change in fibrosis scores and treatment or the presence or absence of steatosis.

Retrospective review of the patients’ notes identified the patient’s weight in 40 cases; the BMI was not available. Alcohol use was recorded in 48 patients, of whom 13 were drinking over 10 units each week, 17 less than 10 units each week, and 18 were abstaining from alcohol at the time of the second biopsy. The viral genotype was determined in 17 cases (eight type 1, one type 2, eight type 3). The year of viral acquisition was known for 18 patients, and could be estimated in 17 patients; history of intravenous drug use and other risk factors was recorded in all cases, as were mean and peak serum ALT concentrations.

Comparison with clinical variables showed that there was a trend for steatosis to be associated with higher weight (p = 0.049), but not alcohol intake or viral genotype (p = 0.5 for both). However, alcohol consumption was significantly associated with the stage of fibrosis (p = 0.029).

Steatosis in the second biopsy correlated with the mean ALT value between biopsies (p = 0.029), and there was a consistent trend for a correlation between mean ALT and necroinflammatory scores (p = 0.039, 0.07, and 0.08 for portal, interface, and lobular inflammation, respectively). Neither steatosis nor fibrosis showed a significant correlation with estimated time since the acquisition of hepatitis C; in addition, the rate of fibrosis was not related to the presence of steatosis.

DISCUSSION

In our study, steatosis was present in 50% of liver biopsies from patients with hepatitis C. The presence of steatosis was significantly correlated with patient age and stage of fibrosis; and multivariate analysis of non-cirrhotic biopsies indicated that steatosis and necroinflammation were independent factors in the development of fibrosis. Our follow up study of 51 patients showed that steatosis, once present, persists and tends to increase with time; a recent study of 96 untreated patients identified worsening steatosis as the only factor independently associated with fibrosis progression on multivariate analysis.18

Whereas steatosis correlated with stage of fibrosis in non-cirrhotic biopsies, the development of cirrhosis was associated with a decrease in steatosis; there was less steatosis in biopsies from patients with cirrhosis than in those with bridging fibrosis (stage 3–5) on biopsy, and less in patients with advanced cirrhosis coming to transplant than in those in whom cirrhosis was diagnosed on routine biopsy for the assessment of chronic hepatitis C. The regression of steatosis in patients with established cirrhosis has been reported previously in patients with hepatitis C11 and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.19 Possible explanations for this include the poor nutritional state of patients with cirrhosis, alterations of intrahepatic circulation and portal–systemic shunting, or the capillarisation of sinusoids.11 In hepatitis C, examination of our transplant hepatectomy specimens showed that steatosis when present affected most hepatocytes in occasional nodules. In view of the suggestion that steatosis is a cytopathic effect of HCV,13 an alternative explanation could be that the absence of steatosis in late cirrhosis reflects selection for the regeneration of hepatocytes resistant to this cytopathic effect.

“Whereas steatosis correlated with stage of fibrosis in non-cirrhotic biopsies, the development of cirrhosis was associated with a decrease in steatosis”

We found a highly significant association between steatosis and stage of fibrosis in non-cirrhotic biopsies, as has previously been demonstrated in several,7,8,13–17 but not all, studies3,10 where this has been examined. However, most of the studies examining histological factors predicting the progression of hepatitis C cited in clinical guidelines for patient management4,5 did not include an assessment of the importance of steatosis. Histopathology scoring systems used in studies of hepatitis C20–23 do not include steatosis, and so the prognostic importance of steatosis has received little attention. Furthermore, recognition and grading of steatosis by histopathologists is much more reproducible than the scoring of interface hepatitis and lobular necroinflammation, currently used in the clinical management of patients with hepatitis C.24

We explored the change in steatosis with time by both a cross sectional study of the effect of age on steatosis, and in follow up biopsies from 51 patients re-biopsied after up to eight years. The cross sectional study showed that steatosis was significantly associated with the patient’s age, independent of the association with stage of fibrosis. For example, of those patients aged under 30 with stage 0–1 disease, 14 of 44 had steatosis, compared with 32 of 50 patients aged over 40 with stage 0–1 disease. This demonstrates a gradual increase over time in the proportion of patients with steatosis, which was also apparent in the patients with follow up biopsies.

The presence of steatosis in patients with hepatitis C is dependant on a complex interaction of viral and host related factors.12 Steatosis in patients without hepatitis C is related to alcohol consumption, obesity, high BMI, type II diabetes, and hyperlipidaemia.25 These factors are also important in patients with hepatitis C, but a proportion of patients with hepatitis C have no other risk factor for steatosis. In particular, this has been reported to be a feature of genotype 3 infection, so that patients with moderate to severe steatosis without other risk factors are probably infected with genotype 3.10 The quantitative association between steatosis and hepatic HCV RNA, the loss of steatosis after viral eradication, and the development of steatosis by transgenic mouse and in vitro cell line models of HCV infection are cited as evidence that steatosis is a direct cytopathic effect of HCV.12 This interacts with factors predisposing to steatosis in the host, particularly high BMI, to result in the expression of steatosis in a proportion of HCV positive patients.11 Recent evidence that weight reduction in patients who are mildly overweight results is improvement in steatosis, and in some also in the degree of fibrosis,11,26 suggests both the reversibility of steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C, and also the direct importance of steatosis in the development of fibrosis.

Take home messages.

Steatosis is strongly associated with increased fibrosis in non-cirrhotic liver biopsies, it increases in prevalence with age, and once present tends to persist

Steatosis is associated with fibrosis independently of necroinflammatory activity, but declines in patients with cirrhosis

Steatosis probably reflects an interaction of viral and host factors important in the generation of fibrosis in the liver, so that those with steatosis in early stage disease may be at increased risk of progressive fibrosis

To understand its role in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C, the assessment of steatosis should be included in the evaluation of biopsies for clinical and research purposes

When we analysed the relation of fibrosis and steatosis with the individual features of necroinflammatory activity in the multivariate analysis, interestingly, disease stage was not associated with increasing patient age after allowing for steatosis and necroinflammation. Both steatosis and necroinflammation remained significant in the model. This suggests that steatosis and necroinflammatory activity may act independently in the mechanisms generating fibrosis. Czaja et al found higher amounts of IgG and more frequent autoantibodies in patients without steatosis, and suggested that the presence or absence of steatosis “may reflect different pathogenic pathways, in which hepatic steatosis may connote cytopathic-predominant processes whereas absence of hepatic steatosis may reflect immune-predominant processes”.11 It has been suggested that steatosis acts by fuelling the free radical production associated with expression of the HCV core protein, amplifying the cytopathic effect of HCV.27

In conclusion, we have confirmed that steatosis is strongly associated with increased fibrosis in non-cirrhotic liver biopsies, it increases in prevalence with age, and once present tends to persist. There is increasing evidence that steatosis reflects an interaction of viral and host factors important in the generation of fibrosis in the liver. Therefore, patients with steatosis in early stage disease may represent a group at increased risk of progressive fibrosis. Future longitudinal or retrospective studies will be required to resolve this issue. The identification of steatosis is a reproducible feature for histopathologists; it appears to reflect a pathogenic pathway distinct from necroinflammatory activity in the generation of fibrosis in liver biopsies. To understand its role in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C, the assessment of steatosis should be included in the evaluation of biopsies for clinical and research purposes.

Abbreviations

ALT, alanine aminotransferase

BMI, body mass index

HCV, hepatitis C virus

REFERENCES

- 1.Fontaine H, Nalpas B, Poulet B, et al. Hepatic activity index is a key factor in determining the natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hum Pathol 2001;32:904–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koukoulis GK. Chronic hepatitic C: grading, staging and searching for reliable predictions of outcome. Hum Pathol 2001;32:899–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yano M, Kumada H, Kage M, et al. The long term pathological evolution of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1996;23:1334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis prognosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Lancet 1997;349:825–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kage M, Shimamatu K, Nakashima E, et al. Long-term evolution of fibrosis from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis in patients with hepatitis C: morphometric analysis of repeated biopsies. Hepatology 1997;25:1028–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seef LB. Natural history of hepatitis C. Hepatology 1197;26 (suppl 1):215–85. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang SJ, Luo J-C, Chu CW, et al. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infections; prevalence and clinical correlation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;16:190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adinolfi LE, Gambardella M, Adreana A, et al. Steatosis accelerates the progression of liver damage of chronic hepatitis C patients and correlates with specific HCV genotype and visceral obesity. Hepatology 2001;33:1358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Sensitivity, specificity and predictability of biopsy interpretations in chronic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1993;105:1824–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubbia-Brandt L, Leandro G, Spahr L, et al. Liver steatosis in chronic hepatitis C: a morphological sign suggesting infection with HCV genotype 3. Histopathology 2001;39:119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Santrach P, et al. Host and disease specific factors affecting steatosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 1998;29:198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quadri R, Rubbia-Brandt L, Abid K, et al. Detection of the negative-strand hepatitis C virus RNA in tissues; implications for pathogenesis. Antiviral Res 2001;52:161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubbia-Brandt L, Quadri R, Abid K, et al. Hepatocyte steatosis is a cytopathic effect of hepatitis C virus genotype 3. J Hepatol 2000;33:106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong VS, Wight DGD, Palmer CR, et al. Fibrosis and other histological features in chronic hepatitis C virus infections: a statistical model. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:465–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adinoffi LE, Utili R, Adreana A, et al. Serum HCV RNA levels correlate with histological liver damage and concur with steatosis in progression of hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci 2001;46:1677–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hourigan LF, MacDonald GA, Purdie D, et al. Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C correlates significantly with body mass index and steatosis. Hepatology 1999;29:1215–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petit JM, Bour JB, Galland-Jos C, et al. Risk factors for diabetes mellitus and early insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2001;35:279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castera L, Hezode C, Routot-Thoraval F, et al. Worsening of steatosis is an independent factor of fibrosis progression in untreated patients with chronic hepatitis C and paired liver biopsies. Gut 2003;52:288–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell EE, Cooksley WG, Hanson R, et al. The natural history of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a follow-up study of 42 patients for up to 21 years. Hepatology 1990;11:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1995;22:696–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bedossa P, Poynard T, Metavir co-operative study group. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1996;24:289–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1981;1:431–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, et al. Classification of chronic hepatitis; diagnosis, grading and staging. Hepatology 1994;19:1513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The French Metavir Cooperative Study Group. Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1994;20:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samerasinghe D, Tasman-Jones C. The associations with hepatic steatosis: a retrospective study. N Z Med J 1992;105:57–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hickman IJ, Clouston AD, Macdonald GA, et al. Effect of weight reduction on liver histology and biochemistry in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2002;51:89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negro F. Hepatitis C virus and liver steatosis: is it the virus? Yes it is, but not always. Hepatology 2002;36:1050–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]