Abstract

Aims: Colonocytes were derived from wild-type (wt) and p53 deficient mice to investigate p53 dependent and independent death pathways after cisplatin treatment, and the role of p53 in growth regulation of primary, untransformed epithelial cells.

Methods: Wt and p53 null colonocytes were exposed to cisplatin and DNA synthesis, apoptosis, and p53, p21, and p73 expression were investigated after six, 12, and 24 hours. Major p73 isoforms were identified by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Results: Cisplatin treated wt cells exhibited cell cycle arrest, whereas p53 null cells continued to synthesise DNA, although both cell types died. Apoptosis was significantly higher in cisplatin treated wt and p53 null colonocytes than in controls at all timepoints, although apoptosis was lower in cisplatin treated p53 null colonocytes than in wt cells. p53 expression was upregulated in cisplatin treated wt colonocytes. p21 expression was high and remained unchanged in cisplatin treated wt cells, although it was reduced in the absence of p53. p73 was investigated because it could account for p53 independent p21 expression and p53 independent death. RT-PCR detected full length p73α. p73 transcript levels remained unchanged, whereas p73 protein accumulated in the nucleus of cisplatin treated cells, irrespective of genotype.

Conclusions: p53 is essential for cell cycle arrest, but not apoptosis in primary murine colonocytes. Apoptosis is reduced in cisplatin treated p53 null cells. Nuclear accumulation of endogenous p73 after cisplatin treatment suggests a proapoptotic role for p73α in the absence of p53 and collaboration with p53 in wt colonocytes.

Keywords: p73α, p53, primary colonocytes, cisplatin

Escape from the induction of apoptosis is believed to be a crucial event in colorectal carcinogenesis. Mutations of p53 are common in colorectal neoplasia but occur late in disease evolution, acting as a progression step.1 Approximately half of all colorectal cancers show p53 gene mutations.2

The role of p53 in tumour suppression is linked to its functions in the regulation of cell cycle control,3 differentiation,4 inhibition of angiogenesis,5 senescence,6 and apoptosis after genotoxic stress, nucleotide depletion, and oncogene activation.7 After DNA damage, p53 induces the expression of p21(WAF1/CIP1), a cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor that causes cell cycle arrest when overexpressed.8 p21 can also bind to proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA),9 blocking its function in DNA replication but not repair.10 Consequently, p21 can cause G1 arrest and inhibition of DNA replication, ensuring that potential errors are repaired before the resumption of cell cycling.

Although the importance of p53 in tumour suppression remains undisputed, it has become apparent that p53 independent mechanisms operate in tandem to ensure the fidelity of replication and the elimination of rogue cells.

Recently, p73 was identified as a p53 homologue, and exhibits considerable sequence and structural similarities. Similar to p53, p73 can transactivate p21, and induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis when overexpressed.11 Moreover, in p53 null cells, oncogene activation induces endogenous p73 expression, engaging an apoptosis pathway that is p53 independent.12 Despite the p73 locus (1p36) being on a chromosome region frequently deleted in human cancers, studies on human tumours have failed to detect p73 gene deletion or inactivating mutations.13,14 The role of p73 in tumorigenesis remains unclear, because silencing of the p73 gene has been detected in neuroblastoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and lung cancer,15 suggesting that p73 may assume a tumour suppressor role. Conversely, overexpression of p73 has been reported in haemopoietic malignancies,16 ovarian,17 bladder,18 and breast cancer.19 Moreover, p73 null mice do not display an increased predisposition to spontaneous tumour development.20

p73 exists as at least six (α, β, γ, δ, ɛ, and η) full length transactivation competent (TA) forms, which differ at the C-terminus, and as N-terminally truncated variants (ΔN).21 Overexpression of the TA isoforms was shown to cause irreversible growth arrest and apoptosis in cells lacking functional p53.22 In contrast, the ΔN variants assume a protective role against apoptosis by directly antagonising the apoptotic functions of p5323 and by suppressing p53 and TAp73 dependent transactivation.24

“Similar to p53, p73 can transactivate p21, and induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis when overexpressed”

Much of the information on carcinogenesis in the intestine derives from studies in the small intestine or cell lines, yet most of the mutations leading to cancer occur in the large intestine. Pioneering work by Potten and others25–27 has elucidated the kinetics of intestinal growth in vivo but primary culture offers a dynamic in vitro model that allows the investigation of growth, apoptosis, and responses to injury.28,29

Therefore, we adapted the colonic crypt isolation technique developed by Booth and colleagues28 to obtain primary colonocytes from adult wt and p53 null mice. Our objectives were to gain a better understanding of the importance of p53 and related proteins in the regulation of growth and response to cisplatin in these cells. Cisplatin crosslinks DNA, forming intrastrand and interstrand adducts. This damage culminates in the induction of apoptosis via at least two different pathways: one involving p53 and the other mediated by p73.30 These pathways have not yet been examined in primary colonocyte cultures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of colonic crypts and culture of primary colonocytes from adult wt and p53 null mice

Wt and p53 null mice31 were humanely killed between 50 and 75 days of age. The crypt isolation technique was successfully adapted from Booth et al.28 NIH-3T3 cells were cultured in double modified eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Cisplatin treatment

After three days in culture, cells were exposed to 15μM cisplatin (David Bull Laboratories, Warwick, UK) for six, 12, or 24 hours.

Proliferation assay

Primary colonocyte cultures were incubated with 0.01 mM (BrdU) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) in culture medium for four hours and fixed in 80% ethanol overnight. Immunodetection of BrdU incorporation was performed using rat anti-BrdU antibody (1/100 dilution) (Oxford Biotechnologies, Oxford, UK) and positive cells were detected using diaminobenzidine. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin. BrdU incorporation was measured by counting the positive nuclei in a total of 500 cells in duplicate. Experiments were performed at least three times with comparable results.

Measurement of apoptosis

For the determination of apoptosis, cells were fixed in modified Bouin’s fixative (85% methanol, 5% acetic acid, and 10% formalin) at 4°C overnight, the DNA denatured in 5M hydrochloric acid, and the nuclei stained with Schiff reagent (Merck, Darnstadt, Germany). We used 0.3% light green as a cytoplasmic counterstain. Apoptosis was measured using morphological criteria,32 with 500 cells counted in duplicate for each timepoint in three separate experiments.

Immunocytochemistry for p53, p21, and p73

The monoclonal antibody against p53 (clone pAB421) was purchased from Calbiochem and mouse anti-p21 (F-5) and rabbit anti-p73 (H-79) from Santa-Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, California, USA). Immunocytochemistry was carried out on 4% paraformaldehyde fixed cells, permeated with 0.5% Triton using an avidin–biotin peroxidase technique, except for p73, which was detected by immunofluorescence using an Alexa-488, conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA). Negative control samples omitted the primary antibody. In addition, p53 null colonocytes were used as a negative control for immunocytochemistry with anti-p53 antibody. For p21 and p53 we counted at least 500 cells for each individual timepoint in three separate experiments.

p73 immunohistochemistry was also performed on formalin fixed paraffin wax embedded mouse colon and skin sections using a peroxidase technique.

Statistics

Data were analysed using Minitab statistical software version 13. Data are presented as the mean (SEM). Comparison of BrdU results was made using ANOVA. Comparison of all other results was made using the Mann-Whitney U test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

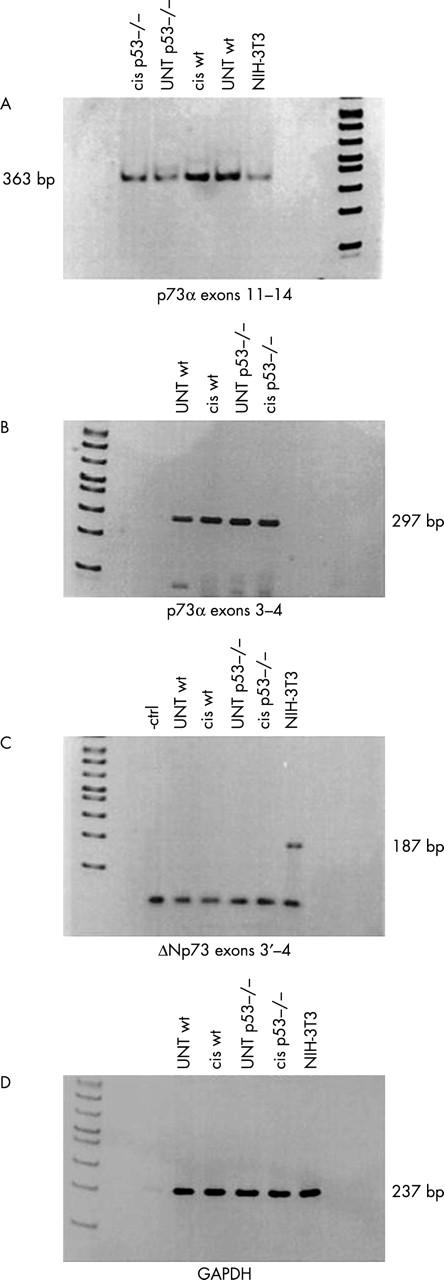

Total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Breda, the Netherlands). Contaminating genomic DNA was removed by treating the total RNA with DNase I (DNAfree kit; Ambion, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK) according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. For cDNA synthesis we used the M-MLV reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) and generated cDNA from 100 ng of total RNA. Amplification of the region between exons 11 and 1433 yields a product of 363 bp in the case of p73α and/or a product of 270 bp in the case of p73β. For the detection of full length forms, primers annealing to exons 3–423 were used, generating a product of predicted size 297 bp. The primers for ΔN forms, annealing to exons 3–4,34 generate a product of 187 bp. Transcript values were normalised to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression (237 bp).35 NIH-3T3 cells of mouse origin were used as positive controls for the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) experiments. Thermocycling was as follows: three minutes at 93°C, followed by 40 cycles of one minute at 93°C, one minute at 52°C (p73α exons 11–14), 64°C (p73α exons 3–4), 61°C (ΔNp73 exons 3–4), or 55°C (GAPDH), and one minute at 72°C, with a final elongation step of five minutes at 72°C. All RT-PCRs were repeated twice using different batches of RNA.

RESULTS

Confirmation of epithelial origin of colonocyte preparation by keratin immunocytochemistry and evaluation of culture purity

Cells derived from colonic crypts by the method cited were of epithelial origin. These cells were cytokeratin positive. Staining for vimentin, characteristic of fibroblasts, proved that fibroblast contamination was minimal (data not shown). Experiments were performed after three days in culture when viability and counts of apoptosis, cell cycle activity, and immunocytochemistry are optimal.

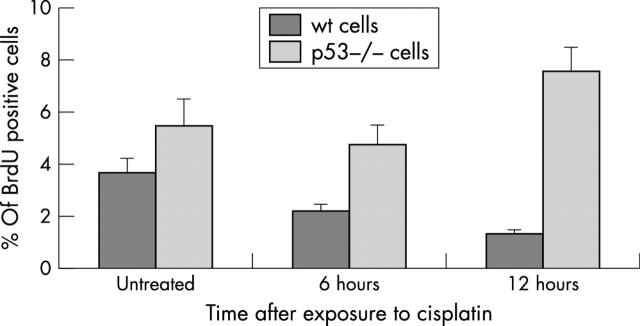

p53 controls growth in primary murine colonocytes

The proportion of cells in S phase was determined by BrdU incorporation into wt and p53 null colonocytes under baseline conditions and after six and 12 hours of exposure to cisplatin. p53 null colonocytes have a growth advantage over wt cells under baseline conditions, exhibiting a significantly higher BrdU labelling index. After cisplatin treatment, BrdU incorporation into wt cells was reduced by 12 hours (p = 0.015, ANOVA), whereas p53 null colonocytes continued to synthesise DNA (fig 1).

Figure 1.

5′-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation into untreated and cisplatin treated wild-type (wt) and p53 null colonocytes. Cells were incubated with BrdU for four hours and immunodetection was performed using rat anti-BrdU antibody. Positive cells were detected by immunocytochemistry and a total of 500 cells counted in triplicate in at least three different experiments. Results are mean (SEM), and show a higher BrdU incorporation in p53 null colonocytes, regardless of treatment and timepoint (p = 0.015, ANOVA).

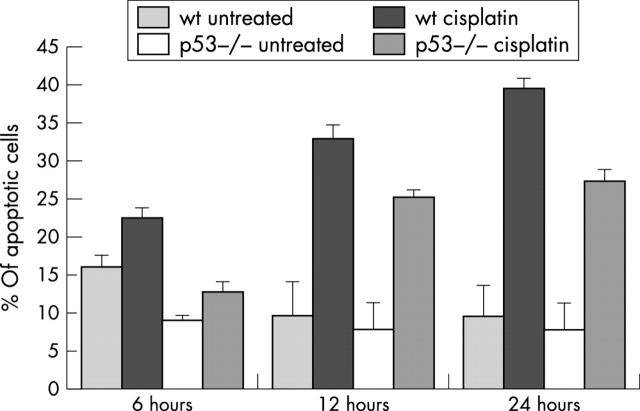

Cisplatin kills colonocytes by apoptosis irrespective of p53 status

Apoptosis in colonocyte cultures was monitored six, 12, and 24 hours after exposure to cisplatin. At all timepoints there was a significant increase in the incidence of apoptosis (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test) between treated cells and their corresponding controls, irrespective of genotype. However, apoptosis was lower in p53 null colonocytes than in wt cells (fig 2): whereas 39% of wt cells were apoptotic 24 hours after exposure to cisplatin, only 27% of p53 null cells had died at this point (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). The overall degree of apoptosis was reduced at each timepoint in p53 deficient colonocytes compared with wt cells.

Figure 2.

Apoptosis in wild-type (wt) and p53 null colonocytes exposed to cisplatin. The Feulgen stain and a 0.3% light green counterstain were used to assess apoptosis in cisplatin treated cells and their corresponding untreated controls. Apoptotic nuclei in a total of 500 cells were counted in triplicate, in at least three experiments. The mean percentages of apoptotic cells (SEM) are shown.

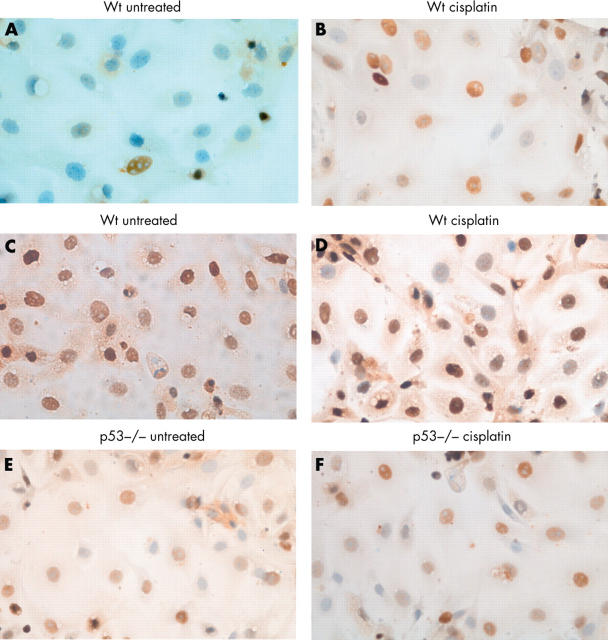

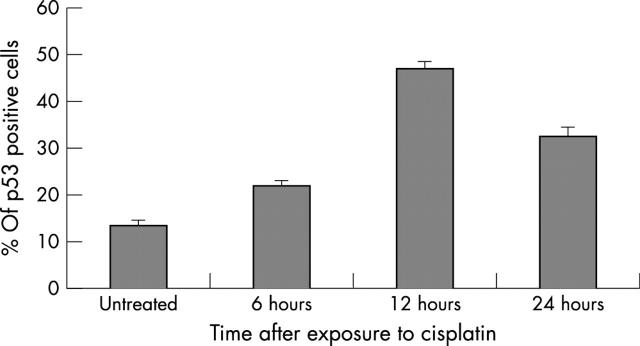

p53 is induced after cisplatin treatment of wt colonocytes

The proportion of cells expressing nuclear p53 was determined by immunocytochemistry on paraformaldehyde fixed, untreated and cisplatin treated colonocytes. Although nuclear p53 was detected under baseline conditions, its expression was significantly increased after exposure to cisplatin (figs 3 and 4) at all timepoints (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test), consistent with its stabilisation and transcriptional activity.

Figure 3.

Expression of nuclear p53 and p21 in untreated and cisplatin treated colonocytes detected by immunocytochemistry using an avidin–biotin peroxidase technique. Positive cells were detected with diaminobenzidine and haematoxylin was used as nuclear counterstain. p53 expression is upregulated after exposure to cisplatin (A and B), whereas p21 levels do not change significantly in cisplatin treated wt cells (C and D) and p53 null cells (E and F).

Figure 4.

p53 expression in untreated and cisplatin damaged colonocytes. p53 is expressed under baseline conditions but its expression is significantly upregulated after exposure to cisplatin at all timepoints (p<0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). The figure shows the mean (SEM) percentage of p53 positive cells in a total of 500.

p21 is expressed in both untreated and cisplatin treated colonocytes

We also investigated the expression of the p53 target gene, p21. High amounts of nuclear p21 were present in both wt and p53 null colonocytes under baseline conditions, with no further increase after cisplatin treatment (fig 3). Interestingly, in the absence of p53, p21 was still expressed but in significantly lower amounts at all timepoints (p = 0.034, Mann-Whitney U test; data not shown).

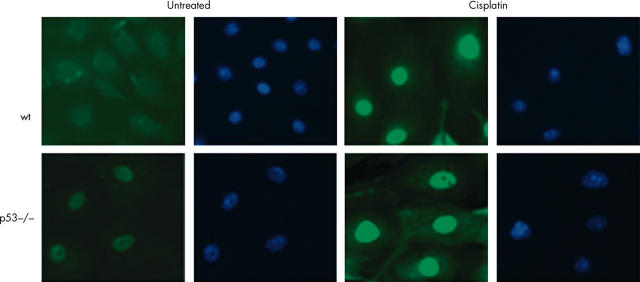

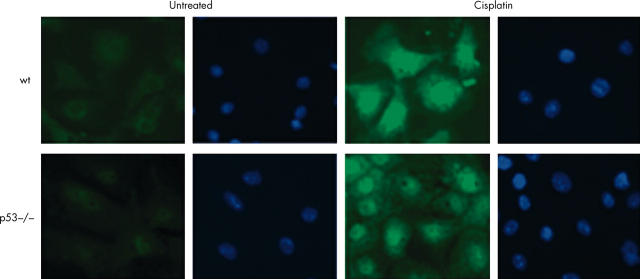

p73 is expressed in wt and p53 null colonocytes

Low baseline expression of nuclear p73 were detectable by immunofluorescence. However, the intensity of the fluorescent signal increased 24 hours after cisplatin treatment, as measured by means of Image Pro-Plus software, consistent with translocation of p73 to the nucleus. Results were comparable using two different antibodies against p73. Rabbit polyclonal H-79 (fig 5) recognises the N-terminal 80 amino acids of p73, and cannot be used to discriminate between full length forms and ΔN variants of p73. Ab77 (fig 6) recognises a sequence at the extreme N-terminal 15 amino acids and therefore exclusively identifies full length p73 and should not crossreact with ΔNp73. To test whether constitutive expression of nuclear p73 is a consequence of in vitro culture or whether it reflects expression in colonic epithelium in situ, formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry with both of the anti-p73 antibodies. Staining was present in the basal/parabasal cells of murine skin epithelium,36 but not in the colonic epithelium, indicating that p73 is not normally expressed, at least in amounts detectable by immunohistochemistry, in the murine large intestine in situ.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescent detection of nuclear p73 in primary colonocytes using Alexa-488 conjugated secondary antibody. Nuclear accumulation of p73 is seen after treatment with cisplatin in both wild-type (wt) and p53 null cells using the rabbit polyclonal H-79 antibody. DAPI was used as a nuclear counterstain. The cells shown were exposed to cisplatin for 24 hours. Images were captured using a Hamamatsu chilled CCD camera and Zeiss fluorescent microscope.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescent detection of nuclear p73 in primary colonocytes using Alexa-488 conjugated secondary antibody. Nuclear accumulation of p73 is seen after treatment with cisplatin in both wild-type (wt) and p53 null cells using the sheep polyclonal Ab77 antibody. DAPI was used as a nuclear counterstain. The cells shown were exposed to cisplatin for 24 hours. Images were captured using a Hamamatsu chilled CCD camera and Zeiss fluorescent microscope.

We also investigated the nature of p73 isoforms in primary colonocytes by RT-PCR and identified the predominant form as full length p73α, present in both wt and p53 null colonocytes with no change during cisplatin treatment (fig 7). No products corresponding to p73β, ΔNp73α, or ΔNp73β were detected.

Figure 7.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showing p73 expression in wild-type (wt) and p53 null untreated (UNT) and cisplatin (cis) treated colonocytes. (A) Amplification with primers spanning exons 11–14 in murine primary colonocytes. The primers could also detect the presence of the C-terminus of p73β, but no band of the predicted size was obtained. (B) RT-PCR analysis for N-terminus detection of full length p73 using primers for exon 3–4. (C) RT-PCR showing the absence of ΔN variants in primary colonocytes. NIH-3T3 cDNA proved that the primers recognise a product of the correct size. (D) The housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal qualitative and semiquantitative control.

DISCUSSION

In our study, we investigated the role of p53 in the regulation of growth and the response to cisplatin injury in freshly isolated, non-transformed primary murine colonocytes and found that whereas p53 seemed to regulate cell cycle arrest after cisplatin induced DNA damage, perhaps its role in apoptosis was less important.

Under baseline conditions, the proportion of p53 null colonocytes in S phase was significantly greater than in the wt counterparts, suggesting a role for p53 in regulating the cell cycle in vitro in primary colonocytes. The decreased BrdU incorporation after treatment with cisplatin in wt colonocytes indicates that wt cells undergo G1 arrest, whereas p53 deficient cells continue to enter the phase of DNA synthesis, despite sustaining damage to their DNA. Thus, as a first line of defence, wt colonocytes respond to cisplatin damage via a p53 dependent growth arrest.

Ultimately, many p53 null and wt cisplatin treated cells died by apoptosis. The time course of cell death was rapid, with approximately 40% of wt cells becoming apoptotic by 24 hours. However, cell death in p53 deficient cells was reduced compared with wt colonocytes. This may be analogous to the delayed p53 independent apoptosis seen in vivo after irradiation in the small intestine, and to a much lesser extent in the colon,37 suggesting the existence of p53 independent mechanisms of eliminating damaged intestinal cells. Consistent with the proposed role for p53 in mediating cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to cisplatin, the expression of p53 was significantly upregulated in treated wt cells. Nonetheless, the expression of its downstream target p21 remained unchanged from the already high baseline. We might predict that these high amounts of p21 function to counteract apoptosis.38 In fact, in the absence of p53, when baseline p21 values are 40% lower, apoptosis is reduced. Expression of nuclear p21 was high regardless of treatment, timepoint, or genotype. This could be attributed to the stress of in vitro culture, which seems to be a limitation of the primary murine colonocyte model. p53 is not normally implicated in the baseline expression of p21, yet in primary colonocytes, the proportion of cells expressing p21 under the normal conditions of in vitro culture is halved in the context of p53 deficiency. If growth in vitro is indeed stressful for colonocytes, then it is not surprising that p21 values are high to counteract this, and that perhaps p53 null cells are to a certain extent desensitised with regard to these stresses. Studies of primary colonocytes lacking p21, both p53 and p21, or p53 and p73 would yield further insight into this question.

Take home messages.

p53 is essential for primary colonocytes to undergo cell cycle arrest but not apoptosis after cisplatin induced damage, suggesting that p53 mediated apoptosis and growth arrest are not the only means by which colonic murine epithelial cells guard against mutation after DNA damage

In the absence of p53, the failure of colonocytes to enter growth arrest probably has no longterm consequences because alternative death pathways are instigated to eliminate cells harbouring mutations

Endogenous p73α was translocated to the nucleus in response to DNA damage in primary murine colonocytes, suggesting a functional proapoptotic role for p73α in p53 deficient cells

“After treatment with cisplatin for 24 hours, there was an increase in the amount of p73 protein in the nucleus as demonstrated by an increase in signal intensity, consistent with increased nuclear translocation of p73”

We detected constitutive expression of p73 in the nucleus of wt and p53 null cells, and increased translocation of p73 to the nucleus after exposure to cisplatin. This suggests that p73 is responsive to cisplatin induced damage of colonocytes and could contribute to the p53 independent expression of p21 and to apoptosis after DNA damage. We used RT-PCR analysis to investigate the incidence of major p73 isoforms in primary colonocytes and confirmed the presence of full length p73α in both wt and p53 null cells under baseline conditions. Amounts of the transcripts remained unchanged after exposure to cisplatin, consistent with reports in the literature that p73 stabilisation after cisplatin induced damage does not involve transcriptional upregulation.39 Nuclear expression of p73 detected by means of immunofluorescence was demonstrated using two different antibodies raised against p73. After treatment with cisplatin for 24 hours, there was an increase in the amount of p73 protein in the nucleus as demonstrated by an increase in signal intensity, consistent with increased nuclear translocation of p73. This is in accord with the possibility that p73α cooperates with p53 in wt colonocytes, as has recently been shown in other systems,40 and that p73α may be a p53 independent pathway of apoptosis in p53 deficient cells. Given the limited yields of colonocyte extract and the low amounts of endogenous p73, we were unable to analyse endogenous p73 by immunoblotting or immunoprecipitation. Several studies have described the transfection of p73 expression plasmids into cancer cell lines for the investigation of p73 modification and interaction with regulatory factors. However, such studies are often confounded by the diversity among cell lines or because they rely on high amounts of exogenous protein and ignore the endogenous protein. Thus, although these approaches are undoubtedly fruitful and very likely to yield useful information, we should be reminded of the power of deciphering function in a physiological setting, such as our primary colonocyte system.

The emerging evidence of the interaction of p73 with components of the mismatch repair signalling pathway,41,42 the high incidence of mismatch repair deficiencies in colorectal cancer, the role of p73 as a corroborator of p53 function and also as an independent apoptosis inducer point to a potentially vital role for p73 in coupling damage repair and death in colonocytes.

In our study we have shown that p53 is essential for primary colonocytes to undergo cell cycle arrest but not apoptosis after cisplatin induced damage. This suggests that p53 mediated apoptosis and growth arrest are neither a major nor a unique protector of colonic murine epithelial cells against mutation after DNA damage. In the absence of p53, the failure of colonocytes to enter growth arrest probably has no longterm consequences because alternative death pathways are instigated to eliminate cells harbouring mutations. Furthermore, we demonstrated the nuclear translocation of endogenous p73α in response to DNA damage in primary murine colonocytes, which, within the context of p53 independent apoptosis, is highly suggestive of a functional proapoptotic role for p73α in these cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK Grant SP2525/0101. NS was supported by BBSRC grant no. 15/C11073.

Abbreviations

BrdU, 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

ΔN, N-terminally truncated variant

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen

RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

TA, transactivation competent

wt, wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1.Carder PJ, Cripps KJ, Morris R, et al. Mutation of the p53 gene precedes aneuploid clonal divergence in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 1995;71:215–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iacopetta B. TP53 mutation in colorectal cancer. Hum Mutat 2003;21:271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kastan MB, Zhan Q, el-Deiry WS, et al. A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia. Cell 1992;71:587–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aloni-Grinstein R, Schwartz D, Rotter V. Accumulation of wild-type p53 protein upon gamma-irradiation induces a G2 arrest-dependent immunoglobulin kappa light chain gene expression. EMBO J 1995;14:1392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dameron KM, Volpert OV, Tainsky MA, et al. Control of angiogenesis in fibroblasts by p53 regulation of thrombospondin-1. Science 1994;265:1582–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atadja P, Wong H, Garkavtsev I, et al. Increased activity of p53 in senescing fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995;92:8348–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan KM, Phillips AC, Vousden KH. Regulation and function of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2001;13:332–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong Y, Hannon GJ, Zhang H, et al. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature 1993;366:701–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores-Rozas H, Kelman Z, Dean FB, et al. Cdk-interacting protein 1 directly binds with proliferating cell nuclear antigen and inhibits DNA replication catalyzed by the DNA polymerase delta holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91:8655–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakanishi M, Robetorye RS, Pereira-Smith OM, et al. The C-terminal region of p21SDI1/WAF1/CIP1 is involved in proliferating cell nuclear antigen binding but does not appear to be required for growth inhibition. J Biol Chem 1995;270:17060–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jost CA, Marin MC, Kaelin WG Jr. p73 is a simian p53-related protein that can induce apoptosis. Nature 1997;389:191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaika A, Irwin M, Sansome C, et al. Oncogenes induce and activate endogenous p73 protein. J Biol Chem 2001;276:11310–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunahara M, Ichimiya S, Nimura Y, et al. Mutational analysis of the p73 gene localized at chromosome 1p36.3 in colorectal carcinomas. Int J Oncol 1998;13:319–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mai M, Yakomizo A, Qian CP, et al. Activation of p73 silent allele in lung cancer. Cancer Res 1998;58:2347–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benard J, Douc-Rasy S, Ahomadegbe JC. TP53 family members and human cancers. Hum Mutat 2003;21:182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters UR, Tschan MP, Kreuzer KA, et al. Distinct expression patterns of the p53-homologue p73 in malignant and normal hematopoiesis assessed by a novel real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay and protein analysis. Cancer Res 1999;59:4233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CL, Ip SM, Cheng D, et al. P73 gene expression in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:3910–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokomizo A, Mai M, Tindall DJ, et al. Overexpression of the wild type p73 gene in human bladder cancer. Oncogene 1999;18:1629–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto T, Oda K, Kubota T, et al. Expression of p73 gene, cell proliferation and apoptosis in breast cancer: immunohistochemical and clinicopathological study. Oncol Rep 2002;9:729–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang A, Sharpe A, McKeon F, et al. p73-deficient mice have neurological, pheromonal and inflammatory defects but lack spontaneous tumours. Nature 2000;404:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X. The p53 family: same response, different signals? Mol Med Today 1999;5:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang L, Lee SW, Aaronson SA. Comparative analysis of p73 and p53 regulation and effector functions. J Cell Biol 1999;147:823–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pozniak CD, Radinovic S, Yang A, et al. An anti-apoptotic role for the p53 family member, p73, during developmental neuron death. Science 2000;289:304–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishimoto O, Kawahara C, Enjo K, et al. Possible oncogenic potential of deltaNp73: a newly identified isoform of human p73. Cancer Res 2002;62:636–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Booth C, Potten CS. Gut instincts: thoughts on intestinal epithelial stem cells. J Clin Invest 2000;105:1493–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potten CS, Booth C, Pritchard DM. The intestinal epithelial stem cell: the mucosal governor. Int J Exp Pathol 1997;78:219–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams ED, Lowes AP, Williams D, et al. A stem cell niche theory of intestinal crypt maintenance based on a study of somatic mutation in colonic mucosa. Am J Pathol 1992;141:773–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Booth C, Patel S, Bennion GR, et al. The isolation and culture of adult mouse colonic epithelium. Epithelial Cell Biol 1995;4:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Booth C, O’Shea JA, Potten CS. Maintenance of functional stem cells in isolated and cultured adult intestinal epithelium. Exp Cell Res 1999;249:359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordan P, Carmo-Fonseca M. Molecular mechanisms involved in cisplatin cytotoxicity. Cell Mol Life Sci 2000;57:1229–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purdie CA, Harrison DJ, Peter A, et al. Tumour incidence, spectrum and ploidy in mice with a large deletion of p53 gene. Oncogene 1994;9:603–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellamy CO, Clarke AR, Wyllie AH, et al. p53 deficiency in liver reduces local control of survival and proliferation, but does not affect apoptosis after DNA damage. FASEB J 1997;11:591–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss RH, Howard LL. p73 is a growth-regulated protein in vascular smooth muscle cells and is present at high levels in human atherosclerotic plaque. Cell Signal 2001;13:727–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sayan AE, Sayan BS, Findikli N, et al. Acquired expression of transcriptionally active p73 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2001;20:5111–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamago G, Takata Y, Furuta I, et al. Suppression of hair follicle development inhibits induction of sonic hedgehog, patched, and patched-2 in hair germs in mice. Arch Dermatol Res 2001;293:435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faridoni-Laurens L, Bosq J, Janot F, et al. P73 expression in basal layers of head and neck squamous epithelium: a role in differentiation and carcinogenesis in concert with p53 and p63? Oncogene 2001;20:5302–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clarke AR, Howard LA, Harrison DJ, et al. p53, mutation frequency and apoptosis in the murine small intestine. Oncogene 1997;14:2015–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahyar-Roemer M, Roemer K. p21 Waf1/Cip1 can protect human colon carcinoma cells against p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptosis induced by natural chemopreventive and therapeutic agents. Oncogene 2001;20:3387–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong JG, Costanzo A, Yang HQ, et al. The tyrosine kinase c-Abl regulates p73 in apoptotic response to cisplatin-induced DNA damage. Nature 1999;399:806–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flores ER, Tsai KY, Crowley D, et al. p63 and p73 are required for p53-dependent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Nature 2002;416:560–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimodaira H, Yoshioka-Yamashita A, Kolodner RD, et al. Interaction of mismatch repair protein PMS2 and the p53-related transcription factor p73 in apoptosis response to cisplatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:2420–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catani MV, Costanzo A, Savini I, et al. Ascorbate up-regulates MLH1 (Mut L homologue-1) and p73: implications for the cellular response to DNA damage. Biochem J 2002;364(Pt 2):441–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]