Abstract

Aims: To evaluate the prognostic impact of tumour angiogenesis assessed by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), microvessel density (MVD), and tumour vessel invasion in patients who had undergone radical resection for stage IB–IIA non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods: Fifty one patients (42 men, nine women; mean age, 62.3 years; SD, 6.9) undergoing complete surgical resection (35 lobectomy, 16 pneumonectomy) of pathological stage IB (n = 43) and IIA (n = 8) NSCLC were evaluated retrospectively. No patient underwent postoperative chemotherapy or neoadjuvant treatment. Tumour specimens were stained for VEGF and specific MVD markers: CD31, CD34, and CD105.

Results: VEGF expression significantly correlated with high CD105 expression (p < 0.0001) and tumour vessel invasion (p = 0.04). Univariate analysis showed that those patients with VEGF overexpression (p = 0.0029), high MVD by CD34 (p = 0.0081), high MVD by CD105 (p = 0.0261), and tumour vessel invasion (p = 0.0245) have a shorter overall survival. Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that MVD by CD34 (p = 0.007), tumour vessel invasion (p = 0.024), and VEGF expression (p = 0.042) were significant predictive factors for overall survival. Finally, the presence of both risk factors, tumour vessel invasion and MVD by CD34, was highly predictive of poor outcome (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.7 to 6.5; p = 0.0002).

Conclusions: High MVD by CD34 and tumour vessel invasion are more closely related to poor survival than the other neoangiogenetic factors in stage IB–IIA NSCLC. This may be because these factors are more closely related to the metastatic process.

Keywords: neoangiogenesis, non-small cell lung cancer, thoracic surgery

Tumour neoangiogenesis has recently been recognised to be important in defining subsets of patients with poor outcome in cancer. 1– 3 Several reports 4– 15 have stated that the presence of neoangiogenesis is a significant factor in terms of overall and disease free survival in lung cancer. Immunohistochemical staining has been used to analyse vasculature markers such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 5 and microvessel density (MVD), as determined by CD31, 6 CD34, 7 and CD105 expression, in archival tumour material. 16 VEGF is a glycoprotein with potent angiogenic, mitogenic, and vascular permeability enhancing activity in endothelial cells. CD31, CD34, and CD105 are endothelial antigens that have been used to highlight the density of intratumorous vessels as a direct marker of the degree of neoangiogenesis. Recently, CD105 proved to be superior to CD34 and CD31 in the evaluation of angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) 15 because it has a greater affinity for activated endothelial cells, whereas CD34 and CD31 can react with both normal vessels and activated vessels.

“Several reports have stated that the presence of neoangiogenesis is a significant factor in terms of overall and disease free survival in lung cancer”

Many patients with early TNM stage have a high probability of recurrence. Despite radical surgery, survival rate ranges between 40% and 70%. 17, 18 Failure is mainly the result of distant recurrences. To date, conventional parameters including analysis of performance status, histology subtype, size of the primary tumour, differentiation grading, and mitotic rate have been investigated with different results. 19, 20

Drawing from this background, we hypothesise that the rate of neoangiogenesis may be helpful in discriminating the probability of a poor prognosis in early stage NSCLC after radical surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Inclusion criteria

Subjects selected for our study were patients who had radical surgery for NSCLC at pathological stage IB (T2N0M0) or IIA (T1N1M0). We combined stages IB and IIA because of their similar prognosis. 17, 18 The patients were staged according to operative and pathological findings based on the AJCC/UICC TNM classification and stage grouping. 17 N-factor was assessed on lymph nodes removed during routine mediastinal lymphadenectomy.

A preoperative staging computed tomography scan was performed in all patients. Only enlarged (greater than 1.5 cm in the maximal diameter) 21 mediastinal lymph nodes were sampled preoperatively, either by mediastinoscopy or video thoracoscopy. The histology of each specimen was assessed according to the World Health Organisation classification, 22 and the pathological stage of each tumour was recorded using the TNM staging system. Histology grading and N-stage were performed on haematoxylin and eosin stained sections.

Patients who did not survive beyond 60 days after surgery were not included in our study to avoid bias from perioperative death. Patients who underwent minimal resection were ruled out from our present analysis.

In addition, only patients who had not received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before and after surgical resection were studied.

Study population

A retrospective study was undertaken in 51 consecutive patients (42 men and nine women), with a mean age of 62.3 years (SD, 6.9; range, 35–75) and stage IB (T2N0) or IIA (T1N1) NSCLC who underwent radical surgical resection at the thoracic surgery department of the Tor Vergata University, Italy between August 1990 and September 1998. The study project was submitted and approved by the human tissue use committee of the university. Tumour histology showed 28 squamous cell carcinomas, 19 adenocarcinomas, and four large cell carcinomas. Table 1 summarises the data.

Table 1.

Study population features divided according to stage

| Conventional risk factors | Total | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 42 | 82.3% |

| Female | 9 | 17.7% |

| Smoker | ||

| No | 6 | 11.7% |

| Yes | 45 | 88.3% |

| Surgical procedure | ||

| Lobectomy | 35 | 68.6% |

| Pneumonectomy | 16 | 31.4% |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous | 28 | 54.9% |

| Non-squamous | 23 | 45.1% |

| Grading | ||

| G1 | 11 | 21.5% |

| G2 | 22 | 43.1% |

| G3 | 18 | 35.4% |

In 16 patients the tumour was resected by pneumonectomy and in 35 by lobectomy.

Methods

Pathological investigations were carried out at the division of pathological anatomy and histology of the Tor Vergata University of Rome and of the University Campus Biomedico of Rome, Italy. NSCLC tumour specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin wax. We selected one representative paraffin wax block from each case. Consecutive 4 μm thick sections were re-cut from each study block and used for the immunohistochemical study.

Immunohistochemical staining for VEGF, CD31, CD34, and CD105 was performed by the streptoavidin–biotin method. In brief, sections were dewaxed and microwave treated at 500 W for five minutes twice in 10mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubation in 0.03% hydrogen peroxide in absolute methanol for 30 minutes at room temperature.

The antibodies used were: a polyclonal antibody against VEGF protein (A-20; 1/200 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA) at room temperature for two hours; a mouse monoclonal antibody against CD31 (JC70; 1/50 dilution; NeoMarkers, Freemont, California, USA) at room temperature for 30 minutes; a mouse monoclonal antibody against CD34 protein (QBEN 10; 1/50 dilution; Dako A\S, Glostrup, Denmark) at room temperature for 30 minutes; and mouse monoclonal antibody against CD105 protein (105CO2; 1/50 dilution; NeoMarkers) at room temperature for 30 minutes. The optimal working dilutions were defined on the basis of a titration experiment. Negative controls for each tissue section were prepared by omitting the primary antibody.

After washing three times with trisphosphate buffered saline (TBS), sections were incubated with biotinylated goat antimouse or antirabbit immunoglobulin G (Dako A\S) for 10 minutes. They were then washed three times with TBS, treated with streptavidin–peroxidase reagent (Dako A\S) for 10 minutes, and then washed with TBS three times again. Finally, specimens were incubated in diaminobenzidine for five minutes, followed by haematoxylin counterstaining. Two experienced investigators (CR and AB) examined the slides, without knowledge of the corresponding clinicopathological data.

The expression of VEGF was assessed according to the percentage of immunoreactive cells in a total of 1000 neoplastic cells (quantitative analysis). The cutoff point to distinguish low from high VEGF expression was 25% of positive carcinoma cells. 5, 21, 22 There was > 95% agreement between the two observers for the VEGF evaluation. A final score was determined by consensus after re-examination.

MVD was assessed using the criteria of Weidner et al. 23 The areas of highest neovascularisation were identified as regions of invasive carcinoma with the highest numbers of discrete microvessels stained for CD31, CD34, and CD105. Any brown stained endothelial cell or endothelial cell cluster that was clearly separate from adjacent microvessels, tumour cells, and other connective tissue elements was considered a single, countable microvessel. Microvessels in sclerotic areas within the tumour, where microvessels were sparse, and immediately adjacent areas of unaffected lung tissue were not considered in vessel counts. Each count was expressed as the highest number of microvessels identified within 0.3 mm2 fields at a magnification of ×400. At least two fields were analysed for each tumour. All counts were performed by two investigators simultaneously, using a doubleheaded light microscope; both had to agree on what constituted a single microvessel before a vessel was included in the count.

Finally, tumour vessel invasion was assessed by identifying neoplastic emboli within the tumour vessels stained by CD34. 5

Follow up

Follow up continued until death or at least until three years from the date of treatment. The survival time was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death; relapse time was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of detection of local recurrence or systemic metastases.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using the SPSS software program (SPSS® 9.05 for Windows 1998; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The χ2 test and Fisher’s two tailed exact test were applied to assess the correlation between immunoreactivity and clinicopathological factors. Correlations between the different variables were adjusted for multiple comparisons. Survival was calculated from the time of surgery to the last date of follow up by means of the Kaplan-Meier estimate and prognosis was compared using the generalised Wilcoxon’s analysis. Continuous variables of neoangiogenesis were split into categorical variables for the presentation of the results, but we performed the statistical analysis of survival before the recategorisation. The cutoff point to distinguish low from high VEGF expression was 25% of positive carcinoma cells, 5, 24, 25 whereas for MVD the median value found in the study group was used.

Factors that were significant on univariate analysis were entered into multivariate analysis using the Cox stepwise logistic regression test to investigate the independence of the various risk factors.

RESULTS

Median follow up of selected patients was 48.1 months (range, 4–150). Median survival was 54 months. At the end of our study, 29 patients had died, 23 of them directly from NSCLC after locoregional (n = 5) or distant (n = 18) relapse. The overall three year survival rate was 58.8% and five year survival was 51.1%, lower than that reported by Mountain 17 (57% and 55%) for pathological stages IB and IIA, respectively.

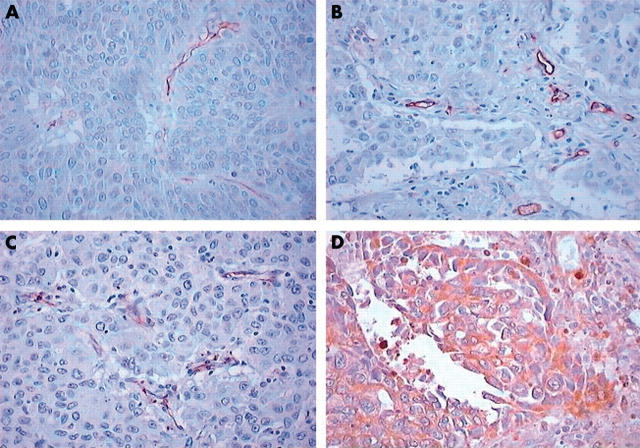

Table 2 shows the immunohistochemical expression of the angiogenetic factors evaluated. The median VEGF rate was 75.1% (range, 2–98%). High expression was seen in 42 patients. The median rate of MVD as assessed by CD34 was 126.8 (range, 62–225), and the value of 130 was chosen as the cutoff point. High expression was seen in 30 patients. The median rate of MVD as assessed by CD31 was 84.6 (range, 57–108) and the value of 80 was chosen as the cutoff point. The median rate of MVD as assessed by CD105 was 57.6 (range, 42–89), and the value of 60 was chosen as the cutoff point. Tumour vessel invasion was present in 13 patients. Figure 1 shows representative examples of staining for CD31, CD34, CD105, and VEGF.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical parameters in patients with NSCLC

| Number | % | |

| CD34 | ||

| Low | 21/51 | 41.2% |

| High | 30/51 | 58.8% |

| CD105 | ||

| Low | 17/51 | 33.3% |

| High | 34/51 | 66.7% |

| CD31 | ||

| Low | 20/51 | 39.2% |

| High | 31/51 | 60.8% |

| VEGF | ||

| Low | 9/51 | 17.6% |

| High | 42/51 | 82.4% |

| Tumour vessel invasion | ||

| No | 38/51 | 74.5% |

| Yes | 13/51 | 25.5% |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Figure 1.

Representative immunostaining for (A) vascular endothelial growth factor, (B) CD31, (C) CD34, and (D) CD105.

None of the conventional factors taken into consideration (age more than 60, sex, type of resection, smoking habit, non-squamous histology, undifferentiated grading, presence of N1 lymph nodes) was significantly related to longterm survival or to the angiogenetic factors examined (table 3 ).

Table 3.

Correlation between angiogenetic factors and conventional risk factors

| VEGF | CD34 | CD31 | CD105 | Vessel invasion | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||||||

| IB | 8 | 35 | 20 | 23 | 17 | 26 | 16 | 27 | 30 | 13 |

| IIA | 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 0 |

| χ2 Value (p value) | 0.008 (0.929) | 1.970 (0.160) | 0.082 (0.775) | 0.908 (0.341) | 1.849 (0.174) | |||||

| Smoker | ||||||||||

| No | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| Yes | 8 | 37 | 18 | 27 | 18 | 27 | 15 | 30 | 32 | 12 |

| χ2 Value (p value) | 0.253 (0.615) | 0.001 (0.979) | 0.017 (0.896) | 0.213 (0.645) | 0.070 (0.791) | |||||

| Surgical procedure | ||||||||||

| Lobectomy | 7 | 28 | 12 | 23 | 11 | 24 | 10 | 25 | 27 | 8 |

| Pneumonectomy | 2 | 14 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 5 |

| χ2 Value (p value) | 0.066 (0.798) | 1.374 (0.241) | 1.892 (0.169) | 0.558 (0.455) | 0.085 (0.770) | |||||

| Histology | ||||||||||

| Squamous | 4 | 24 | 9 | 19 | 13 | 15 | 10 | 18 | 21 | 7 |

| Non-squamous | 5 | 18 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 16 | 7 | 16 | 17 | 6 |

| χ2 Value (p value) | 0.106 (0.745) | 1.347 (0.246) | 0.767 (0.381) | 0.010 (0.921) | 0.055 (0.815) | |||||

| Grading | ||||||||||

| G1 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 1 |

| G2 | 3 | 19 | 8 | 14 | 8 | 14 | 5 | 17 | 17 | 5 |

| G3 | 2 | 16 | 4 | 14 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 7 |

| χ2 Value (p value) | 3.424 (0.180) | 1.382 (0.876) | 0.255 (0.880) | 2.091 (0.352) | 3.347 (0.188) | |||||

VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Analysis of the correlation between VEGF expression and the other neoangiogenetic factors showed that VEGF overexpression was significantly correlated with high CD105 (p < 0.0001) and tumour vessel invasion (p = 0.04) (table 4 ).

Table 4.

Correlation between vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression and the other neoangiogenetic factors

| VEGF | ||||

| Low | High | χ2 | p Value | |

| CD34 | ||||

| Low | 6 (12%) | 15 (29%) | 1.793 | 0.181 (NS) |

| High | 3 (6%) | 27 (53%) | ||

| CD31 | ||||

| Low | 5 (10%) | 15 (29%) | 0.533 | 0.465 (NS) |

| High | 4 (8%) | 27 (53%) | ||

| CD105 | ||||

| Low | 8 (16%) | 9(18%) | 12.295 | <0.0001 |

| High | 1 (2%) | 33 (64%) | ||

| Vessel invasion | ||||

| No | 9 (18%) | 29 (56%) | 2.297 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 13 (26%) | ||

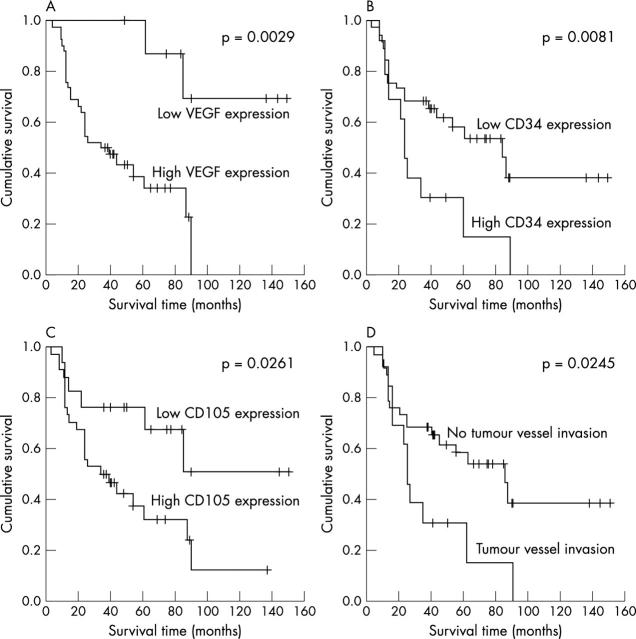

Univariate analysis, performed by five year Kaplan-Meier survival rate for dichotomised variables, showed a significant association with VEGF overexpression (p = 0.0029), with high MVD by CD34 (p = 0.0081) and by CD105 (p = 0.0261), and with tumour vessel invasion (p = 0.0245). These data are summarised in table 5 and fig 2 .

Table 5.

Survival and immunohistochemical parameters in patients with NSCLC analysed by univariate analysis

| Median survival (months) | 95% CI | p Value | |

| CD 34 | |||

| Low | 92 | 65 to 120 | 0.0081 |

| High | 24 | 8 to 40 | |

| CD105 | |||

| Low | 100 | 68 to 131 | 0.0261 |

| High | 34 | 9 to 59 | |

| CD31 | |||

| Low | 90 | 40 to 140 | 0.0429 |

| High | 26 | 8 to 44 | |

| VEGF | |||

| Low | 128 | 101 to 154 | 0.0029 |

| High | 34 | 18 to 50 | |

| Tumour vessel invasion | |||

| No | 85 | 51 to 119 | 0.0245 |

| Yes | 24 | 19 to 29 | |

CI, confidence interval; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for the study population stratified for the various neovascularisation factors. (A) VEGF expression. The five year overall survival rate was 88% for low expression (⩽ 25%) and 39.2% for overexpression (> 25%). (B) Microvessel density (MVD) assessed by CD34. The five year overall survival rate was 69.6% for low (⩽ 130) and 29.5% for high (> 130) MVD. (C) MVD assessed by CD105. The five year overall survival rate was 76.5% for low (⩽ 60) and 37.7% for high (> 60) MVD. (D) Tumour vessel invasion. The five year overall survival rate was 30.9% when present and 60.9% when absent.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that MVD as assessed by CD34 (odds ration (OR), 3.5; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.408 to 8.702; p = 0.007), tumour vessel invasion (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.148 to 6.913; p = 0.024), and VEGF expression (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.054 to 14.61; p = 0.042) were significant predictive factors for overall survival (table 6 ).

Table 6.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of overall survival in patients with NSCLC

| RR of death | 95% CI | p Value | |

| CD34 | |||

| Low | 1 | – | 0.007 |

| High | 3.501 | 1.408 to 8.702 | |

| CD105 | |||

| Low | 1 | – | 0.792 |

| High | 1.141 | 0.429 to 3.036 | |

| CD31 | |||

| Low | 1 | – | 0.066 |

| High | 2.225 | 0.950 to 5.214 | |

| VEGF | |||

| Low | 1 | 0.042 | |

| High | 3.617 | 1.054 to 14.61 | |

| Tumour vessel invasion | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.024 |

| Yes | 2.817 | 1.148 to 6.913 | |

CI, confidence interval; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; RR, relative risk; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

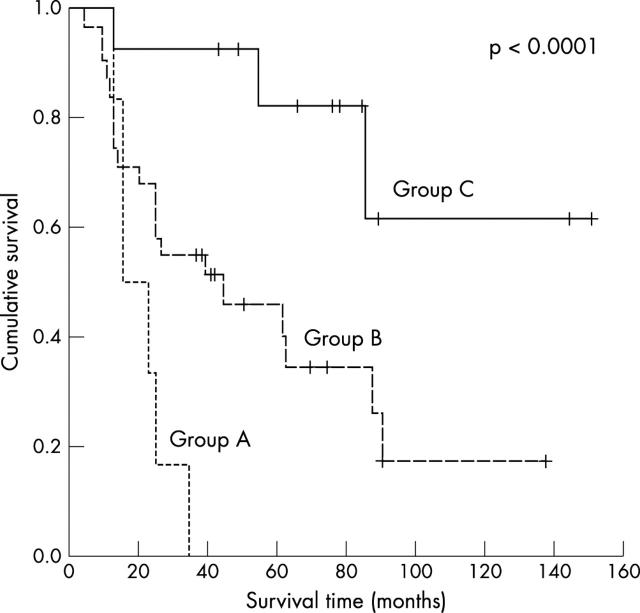

The presence of both risk factors, tumour vessel invasion and MVD as assessed by CD34, was highly predictive of poor outcome (p = 0.0002; OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.7 to 6.5). These data are shown in table 7 and fig 3 .

Table 7.

Survival and combination of CD34 and tumour invasion in patients with NSCLC

| Groups | Median survival (months) | 95% CI | p Value |

| A (CD34+/TVI+) | 15 | 7 to 23 | <0.0001 |

| B (CD34−/TVI+, CD34+/TVI−) | 44 | 6 to 82 | |

| C (CD34−/TVI−) | 116 | 84 to 148 |

CI, confidence interval; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TVI, tumour vessel invasion.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve for the study population for combined tumour vessel invasion and microvessel density as assessed by CD34. The five year overall survival rate was 77.3% for no positive factor, 43.2% for one positive factor, and 0% for two positive factors.

DISCUSSION

Angiogenesis is an essential process in the progression of malignant tumours. A variety of proteins, including growth factors and extracellular matrix enzymes, have been recognised to be potent inducers of angiogenesis. 26 Recent evidence suggests that tumour angiogenesis is associated with patient outcome in several malignancies. Therefore, neoangiogenesis may become an integral part of a more consistent staging system. The first study correlating MVD with prognosis in NSCLC was that of Macchiarini and colleagues 4 in 1992, who assessed neovascularisation by the use of anti-factor VIII. Later, factor VIII, 6, 27 CD34, 9, 11 and VEGF expression, 5, 10, 12– 14, 28, 29 in addition to non-vascular growth factors 30 were investigated. Comparisons and meta-analysis are very difficult to perform because of the different methodologies and evaluation criteria for VEGF and MVD used, in addition to the heterogeneity of the study samples (table 8 ).

Table 8.

Studies correlating neoangiogenesis and survival in NSCLC

| First author | Year | Number of patients | Stage | Factor | Correlation |

| Giatromanolaki 6 | 1997 | 134 | I, II | CD31 | NS |

| Pastorino 8 | 1997 | 137 | I | CD31 | NS |

| Fontanini 9 | 1997 | 407 | I–III | CD34 | S |

| Duarte 26 | 1998 | 106 | I | VIII, CD31 | S, NS |

| Imoto 27 | 1998 | 91 | I–III | VEGF | S |

| Matsuyama 11 | 1998 | 101 | I–III | CD34 | S |

| Decaussin 12 | 1999 | 81 | I, II | VEGF | NS |

| Kakolyris 13 | 1999 | 69 | I, II | CD31 | S |

| Yano 5 | 2000 | 108 | I–IV | CD34, VEGF | S, NS |

| Koukourakis 10 | 2001 | 102 | I, II | VEGF | S |

| Han 14 | 2001 | 85 | I | VEGF | S |

| Offersen 7 | 2001 | 143 | I–III | VEGF, CD34 | NS, NS |

| Tanaka 15 | 2001 | 236 | I–III | CD105, CD34 | S, NS |

NS, not significant; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; S, significant; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Such different results highlight the need for more reliable markers of neoangiogenesis. Nevertheless, recently Meert and colleagues 26 performed a meta-analysis based on a systematic review of the literature to assess the prognostic value on survival of microvessel count in patients with lung cancer. They found that a high MVD was a significantly poor prognostic factor for survival in NSCLC, however it was assessed (factor VIII, CD34, or CD31).

The purpose of our study was to identify the best markers of neoangiogenesis and correlate them to survival in a group of patients with early stage NSCLC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study dealing with such a wide panel of factors in such a selected group of patients.

Our data show that patients classified at the same prognostic stage according to classic morphological criteria have very variable prognoses. Within this group, we found that some markers of neoangiogenesis were useful tools to characterise patients with a poor outcome.

“Interestingly, CD105 proved to be a significant marker of neoangiogenesis, but it was excluded at multivariate analysis”

Our results show that high VEGF expression, high MVD as assessed by CD105 and CD34, and tumour vessel invasion are good markers of angiogenesis and are significantly correlated with a poor survival rate. Nevertheless, at multivariate analysis, only MVD assessed by CD34 and tumour vessel invasion were selected by the statistical model. The combination of these two markers classified three populations with different risks of dying.

Interestingly, CD105 proved to be a significant marker of neoangiogenesis, but it was excluded at multivariate analysis. This finding contrasts with the results of Tanaka et al, 15 who found that CD105 expression was the best marker of angiogenesis and was a significant prognosticator of disease free survival, superior to CD34. This apparent contradiction might be explained by the fact that CD34 and tumour vessel invasion are more strictly related to the metastatic process than neoangiogenesis by itself. Yano et al have recently demonstrated a higher incidence of distant metastases and a shorter survival in patients with high grade MVD as assessed by CD34. 5 A significant correlation was also shown between CD34 and tumour vessel invasion.

Take home messages .

Patients with non-small cell lung cancer with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) overexpression, high microvessel density (MVD) by CD34 and CD105, and tumour vessel invasion had shorter overall survival on univariate analysis

Multivariate analysis showed that MVD by CD34, tumour vessel invasion, and VEGF expression were significant predictive factors for overall survival

The presence of both tumour vessel invasion and MVD by CD34 was highly predictive of poor outcome and might be useful to identify a subset of high risk patients who could be targeted for more aggressive treatment

The limitations of our study are the small sample size and the length of the minimum follow up required. As far as the size of the study group is concerned, we chose only a particular subset of patients (stages IB–IIA) to avoid bias resulting from different prognoses. Indeed, even if these patients are staged into different classes the prognosis is similar. 17, 18 Conversely, stage I, compounded with IA and IB, is a heterogeneous group. Nevertheless, despite the relatively short follow up period, we were able to demonstrate a significant impact of the expression of the analysed factors on survival.

CONCLUSIONS

We have confirmed previous work claiming that VEGF, CD105, and CD34 are excellent markers of neoangiogenesis in NSCLC (table 4 ). In our study, the overexpression of these factors correlated with poor prognosis in a homogeneous group of patients who underwent radical surgery. The two factors indicative of the metastatic process, CD34 and tumour vessel invasion, correlated closely with poor prognosis, and their combination may be useful to stratify patients into three different populations with a low, intermediate, and high risk of short survival. 30

Our research group is presently investigating the expression of several angiogenetic markers on a wider sample of NSCLCs to provide a better definition of their potential prognostic value. The identification of a high risk subset of patients may be useful so that these patients can be given adjuvant therapy (although the role of such treatment is presently still debatable) or a targeted and specific treatment in the near future. 31

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out within the Fellowship Research programme Dottorato di Oncologia Toracica by the University of Rome Tor Vergata. This study was funded by a grant from the Italian Health Ministry (title of the project: “Profilo genetico associato al fenotipo metastatico e alla prognosi nei tumori polmonari”) and by a grant 60% 2002 from the Tor Vergata University. We thank Dr S Servetti for her help in editing this paper.

Abbreviations

CI, confidence interval

MVD, microvessel density

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer

OR, odds ratio

TBS, trisphosphate buffered saline

VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

REFERENCES

- 1. Weidner N. Intratumor microvessel density as a prognostic factor in cancer. Am J Pathol 1995;147:9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takahashi Y, Kitadai Y, Bucana CD, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR, correlates with vascularity, metastasis, and proliferation of human colon cancer. Cancer Res 1995;55:3964–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weidner N. Tumoural vascularity as a prognostic factor in cancer patients: the evidence continues to grow. J Pathol 1998;184:119–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Macchiarini P, Fontanini G, Hardin MJ, et al. Relation of neovascularization to metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Lancet 1992;340:145–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yano T, Tanikawa S, Fujie T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression and neovascularisation in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:601–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giatromanolaki A, Koukourakis MI, Theodossiou D, et al. Comparative evaluation of angiogenesis assessment with anti-factor-VIII and anti-CD31 immunostaining in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1997;3:2485–92.9815651 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Offersen BV, Pfeiffer P, Hamilton-Dutoit S, et al. Patterns of angiogenesis in nonsmall-cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 2001;91:1500–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pastorino U, Andreola S, Tagliabue E, et al. Immunocytochemical markers in stage I lung cancer: relevance to prognosis. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fontanini G, Vignati S, Boldrini L, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with neovascularization and influences progression of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 1997;3:861–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, O’Byrne KJ, et al. Potential role of bcl-2 as a suppressor of tumour angiogenesis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 1997;74:565–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsuyama K, Chiba Y, Sasaki M, et al. Tumor angiogenesis as a prognostic marker in operable non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:1405–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Decaussin M, Sartelet H, Robert C, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its two receptors (VEGF-R1-Flt1 and VEGF-R2-Flk1/KDR) in non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs): correlation with angiogenesis and survival. J Pathol 1999;188:369–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kakolyris S, Giatromanolaki A, Koukourakis M, et al. Assessment of vascular maturation in non-small cell lung cancer using a novel basement membrane component, LH39: correlation with p53 and angiogenic factor expression. Cancer Res 1999;59:5602–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Han H, Silverman JF, Santucci TS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in stage I non-small cell lung cancer correlates with neoangiogenesis and a poor prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol 2001;8:72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tanaka F, Otake Y, Yanagihara K, et al. Evaluation of angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer. Comparison between anti-CD34 and anti-CD105 antibody. Clin Cancer Res 2001;7:3410–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kumar P, Wang JM, Bernabeu C. CD105 and angiogenesis. J Pathol 1996;178:363–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mountain FC. Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 1997;111:1710–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naruke T, Tsuchiya R, Kondo H, et al. Implication of staging in lung cancer. Chest 1997;112:242S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harpole DH, Herndone JE, Young WG, et al. Stage I non small cell lung cancer: a multivariate analysis of treatment methods and patterns of recurrence. Cancer 1995;76:787–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jazieh AR, Hussain M, Howington JA, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with surgically resected stages I and II non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:1168–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Breyer RH, Karstaedt N, Mills SA, et al. Computed tomography for evaluation of mediastinal lymph nodes in lung cancer: correlation with surgical staging. Ann Thorac Surg 1984;38:215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. WHO. Histological typing of lung cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 1982;77:123–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, et al. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis—correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mattern J, Koomagi R, Volm M. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression and angiogenesis in non-small cell carcinomas. Int J Oncol 1995;6:1059–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Silverman JF, Santucci TS, Macherey RS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in stage I non-small cell lung cancer correlates with neoangiogenesis and a poor prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol 2001;8:72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meert AP, Paesmans M, Martin B, et al. The role of microvessel density on the survival of patients with lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2002;87:694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duarte IG, Bufkin BL, Pennington MF, et al. Angiogenesis as a predictor of survival after surgical resection for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;115:652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Imoto H, Osaki T, Taga S, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in non-small-cell lung cancer: prognostic significance in squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;115:1007–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ohta Y, Nozawa H, Tanaka Y, et al. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor-C and decreased NM23 expression associated with microdissemination in the lymph nodes in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;119:804–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Siegfried JM, Weissfeld LA, Luketich JD, et al. The clinical significance of hepatocyte growth factor for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:1915–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shepherd FA. Angiogenesis inhibitors in the treatment of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2001;34:S81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]