Abstract

Targeted cancer treatments rely on understanding signalling cascades, genetic changes, and compensatory programmes activated during tumorigenesis. Increasingly, pathologists are required to interpret molecular profiles of tumour specimens to target new treatments. This is challenging because cancer is a heterogeneous disease—tumours change over time in individual patients and genetic lesions leading from preneoplasia to malignancy can differ substantially between patients. For childhood tumours of the nervous system, the challenge is even greater, because tumours arise from progenitor cells in a developmental context different from that of the adult, and the cells of origin, neural progenitor cells, show considerable temporal and spatial heterogeneity during development. Thus, the underlying mechanisms regulating normal development of the nervous system also need to be understood. Many important advances have come from model mouse genetic systems. This review will describe several mouse models of childhood tumours of the nervous system, emphasising how understanding the normal developmental processes, combined with mouse models of cancer and the molecular pathology of the human diseases, can provide the information needed to treat cancer more effectively.

Keywords: retinoblastoma, medulloblastoma, neuroblastoma, retrovirus, xenograft

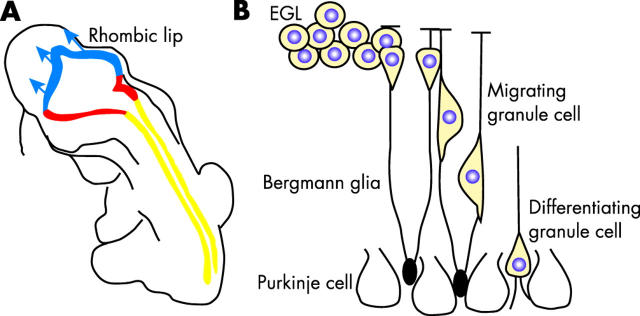

In many forms of adult cancer, the cell of origin is well understood; this understanding is based on the location of the tumour, the molecular markers expressed in the tumour cells, and the histological and clinical features of the disease. However, even for well characterised adult cancers, it is widely accepted that tumorigenesis is a multistage process involving sequential genetic or epigenetic changes. 1 For example, cells that re-enter the cell cycle must become growth factor independent, escape apoptosis, maintain their telomeres, reorganise the surrounding vasculature, and acquire invasive properties to become metastatic cancer (fig 1A ). 1 Because tumour cells change so dramatically over time, there is considerable heterogeneity at both the molecular and histopathological levels (fig 1B ). This heterogeneity becomes more complex when we consider that tumour cells from different patients can undergo different genetic changes (fig 1C ), and a single tumour may be composed of a mixture of cells at various stages of tumorigenesis. For example, approximately 20% of neuroblastomas exhibit an amplification of the MYCN gene, but the other 80% are believed to undergo distinct genetic changes. 2

Figure 1.

Tumours exhibit temporal and spatial heterogeneity. (A) The transition from preneoplastic lesion to metastatic cancer is believed to involve multiple genetic or epigenetic changes including growth factor independence, escape of apoptosis, preservation of telomeres, recruitment of vasculature, and acquisition of invasive properties. (B) Retinoblastomas exhibit histological heterogeneity, such as Homer-Wright rosettes, which lack a lumen, and Flexner-Wintersteiner rosettes, which contain an obvious lumen. Another histological feature of some retinoblastomas are vitreal seeds, which are small clusters of cells that are free floating in the vitreous of the eye. In some tumours, glial fibrilary acidic protein (GFAP) immunopositive glial cells surround the vessels (CD31), whereas in other tumours, such glial association is absent. The protein p21 is an example of molecular heterogeneity in retinoblastoma. Some nuclei of the viable tumour are clearly p21 immunopositive, and others are p21 immunonegative. In contrast, PTEN is expressed in almost all retinoblastoma cells. (C) Different pathways lead to tumorigenesis. In neuroblastoma, MYCN amplification accounts for a subset of the most aggressive tumours, and serial analysis of the same tumours revealed that tumours lacking MYCN amplification early, rarely acquire such mutations later. Thus, there are probably distinct pathways (MYCN amplification and non-MYCN amplification) that lead to neuroblastoma. In medulloblastoma in the mouse, a variety of genetic alterations can lead to tumour formation. Interestingly, many of these mutations in distinct pathways eventually lead to Gli1 activation, which is important for tumour proliferation. Thus, disparate pathways may converge on a common target, Gli1. In retinoblastoma, most tumours share a common initiating event—RB (the retinoblastoma gene) inactivation. After RB inactivation and subsequent deregulated growth, the different tumours might progress down distinct, divergent pathways leading to malignant transformation. gcl, ganglion cell layer; inbl, inner nuclear basal layer; inl, inner nuclear layer; onbl, outer nuclear basal layer; onl, outer nuclear layer.

For childhood tumours of the nervous system, the cell of origin and the environment in which tumorigenesis occurs are much more difficult to define. Many of these tumours arise from neural progenitor cells, which constantly undergo changes over the course of development (fig 2 ) in a highly dynamic environment. 3– 6 Unlike most adult tumours, developmental tumours proliferate in an environment rich in growth factors. 5, 7, 8 Moreover, in the developing nervous system, mitotic and postmitotic cells migrate in a series of carefully choreographed patterns. 9– 11 Once these cells reach their destination, apoptosis precisely trims away a small subset of the neurones and glia. 12 Blood vessels that supply the nervous system also rapidly expand in patterns directed by the developing neurones and glia. 13 If proliferation becomes deregulated as a result of genetic and possibly epigenetic changes in the neural progenitor cells, then several compensatory mechanisms within the progenitor cells prevent developmental disasters. 5 Efforts to understand each step of tumorigenesis in the context of this changing neural progenitor cell population and dynamic environment have resulted in some exciting discoveries that can help molecular pathologists elucidate the underlying defects in childhood tumours of the nervous system, which is a necessary first step towards helping clinicians target treatments for these malignancies.

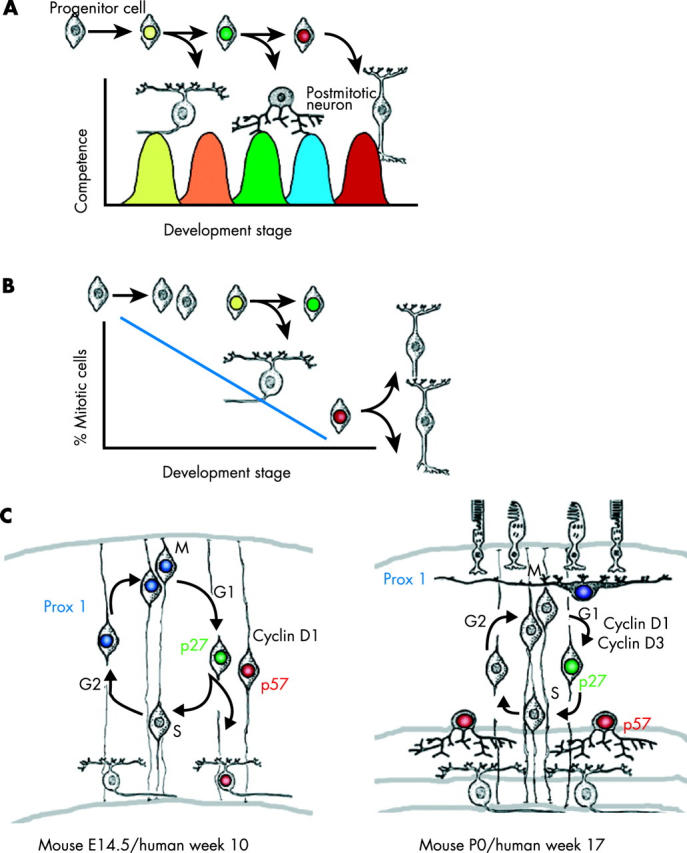

Figure 2.

Neural progenitor cells exhibit temporal and spatial heterogeneity. (A) During the development of the nervous system, progenitor cells pass through distinct stages of competence in a unidirectional manner. These stages are defined by the ability of progenitor cells to give rise to different subsets of differentiated neurones or glia. For example, early stage progenitor cells are competent to give rise to only early born cell types, and late stage progenitor cells are competent to give rise to only late born cell types. (B) Patterns of proliferation or cell division change over time in concert with the changes in progenitor cell competence. Early during development, progenitor cells tend to give rise to more proliferating, immature progenitor cells. Later, a mixture of postmitotic daughter cells and mitotic daughter cells is generated. At the end of histogenesis, neural progenitor cells undergo terminal cell cycle exit and produce postmitotic neurones and glia. Neural progenitor cells may be more susceptible to transformation at particular stages of development. (C) Some of the molecules involved in the temporal and spatial heterogeneity of the developing retina have been identified. These include both cell cycle proteins (p27, p57, cyclin D1, and cyclin D3) and transcription factors (Prox1). In the embryonic retina, some progenitor cells use p27 to exit the cell cycle, and others use p57; this is an example of spatial heterogeneity. Similar results have been obtained with cyclins D1 and D3. Prox1 is expressed in a subset of dividing retinal progenitor cells embryonically, a finding that indicates that there is spatial heterogeneity for this homeobox gene. Interestingly, Prox1 also exhibits temporal heterogeneity, because late stage progenitor cells do not use Prox1 at all. During later stages of development, Prox1 is expressed only in postmitotic horizontal cells. E, embryonic day; P, postnatal day.

“Approximately 20% of neuroblastomas exhibit an amplification of the MYCN gene, but the other 80% are believed to undergo distinct genetic changes”

A better understanding of the normal developmental processes that regulate the formation of the nervous system has contributed to our understanding of tumorigenesis in those tissues and is helping target cancer treatment. Many of the major advances in our understanding of developmental neurobiology have come from genetic studies in model systems such as mice. For example, a transgenic model of neuroblastoma that recapitulates MYCN amplification in neural crest progenitor cells relied on the understanding of normal neural crest development to target ectopic MYCN expression to the appropriate cell at the appropriate time during development. 14 In addition, early work on the role of the hedgehog signalling pathway in cerebellar development provided a crucial link between mutations in this pathway and medulloblastoma, 15 Similarly, recent advances in our understanding of the role of the retinoblastoma (RB) family of proteins in regulating retinal development has been a key factor in designing in vivo genetic models that faithfully recapitulate human retinoblastoma (M A Dyer, unpublished data, 2004). Although mouse models have their limitations, when they are combined with xenograft models using human tumour cell lines and molecular pathological findings in patients with the disease, they can provide some of the missing links that may have otherwise been overlooked. Taken together, these examples highlight the importance of synergistic approaches to the treatment of childhood malignancies of the developing nervous system.

“A better understanding of the normal developmental processes that regulate the formation of the nervous system has contributed to our understanding of tumorigenesis in those tissues and is helping target cancer treatment”

Neural stem cells and neural progenitor cells

The cell of origin in many childhood tumours of the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system is an immature dividing cell. Experimental evidence indicates that there are two distinct populations of proliferating undifferentiated cells: progenitor cells and stem cells. 4, 16 In both the central and peripheral nervous systems, multipotent, dividing progenitor cells undergo progressive rounds of cell division and give rise to different classes of neurones and glia at different stages of development. 5, 6, 17, 18 Neural crest progenitor cells also have the potential to give rise to non-neuronal cells, including cartilage and melanocytes. 19, 20 Neural progenitor cells are thought to undergo unidirectional changes in their competence to give rise to the different cell populations. 4 That is, the potential of an early stage progenitor cell is different from that of a late stage progenitor cell. At the end of histogenesis, when all of the cell types have been generated, the last remaining neural progenitor cells exit the cell cycle and undergo terminal differentiation. Neural progenitor cells share many features with neural stem cells; however, there are two important distinctions. First, progenitor cells do not retain their potential to make all of the cell types in the tissue of interest. As mentioned above, with successive rounds of cell division, the developmental potential of progenitors becomes more restricted. Second, progenitor cells do not retain an unlimited proliferative potential; that is, they eventually undergo terminal cell cycle exit, and the differentiated neurones and glia rarely re-enter the cell cycle. 5, 21 Thus, stem cells are a specialised subset of progenitor cells that retain the ability to give rise to all the cell types in the tissue and to self renew by cell division. 22 It is difficult to identify stem cells during development, because they are so similar to progenitor cells, and because the lineage relation between neural stem cells and neural progenitor cells has not been elucidated for most regions of the nervous system. 23– 25 Many of the best characterised stem cells have been studied in fully differentiated tissues, because they are much easier to identify when surrounded by postmitotic differentiated cells. It is also important to point out that many of these stem cell populations have been defined only experimentally and as yet have no normal in vivo function. 16 Of course, this is of little consequence when considering the use of these cells for the treatment of degenerative disorders. 26 Yet, in childhood cancer of the nervous system, we are concerned primarily with the normal and aberrant function of progenitor cells, because they make up most of the cells in the developing nervous system and are most likely to be the cells that undergo genetic alterations that ultimately give rise to cancer. It cannot be ruled out that childhood cancer of the nervous system arises from stem cells in those tissues, but current estimates of stem cell frequency in the developing neural crest, 27 cerebellum, 28 and retina 16 suggest that this is probably not the case. Moreover, neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, and retinoblastoma are rarely diagnosed in adults, who are believed to retain stem cells in each of these neural tissues.

NEUROBLASTOMA

Clinical features

There are approximately 700 new cases of neuroblastoma each year in the USA so that neuroblastoma accounts for 7.5% of all childhood (patients < 15 years old) cancer. 29 Neuroblastoma is more prevalent in younger children (< 5 years old), and it is the most common cancer in infants (< 1 year old). This cancer is believed to arise from neural crest progenitors in the peripheral nervous system during development. 2 Neuroblastoma exhibits considerable clinical heterogeneity, 2 which probably reflects genetic heterogeneity in the tumour cells, heterogeneity of the progenitor cell population in which the tumour arises, or both. In some infants, the tumour undergoes spontaneous regression or presents as a benign ganglioneuroma. However, children older than 1 year who present with neuroblastoma have a poor prognosis as a result of extensive metastases. 30

Neural crest development

The neural crest is a transient, highly migratory population of multipotent progenitor cells that gives rise to the neurones and glia of the peripheral nervous system and other diverse cell types such as melanocytes and cranial cartilage. 19, 20 During early development, the dorsal neural tube gives rise to neural crest precursor cells; this stage of development is characterised by an epithelial–mesenchymal transition. That is, the neural crest cells exhibit a “fibroblast-like” mesenchymal morphology, which is characteristic of cells that migrate over long distances.

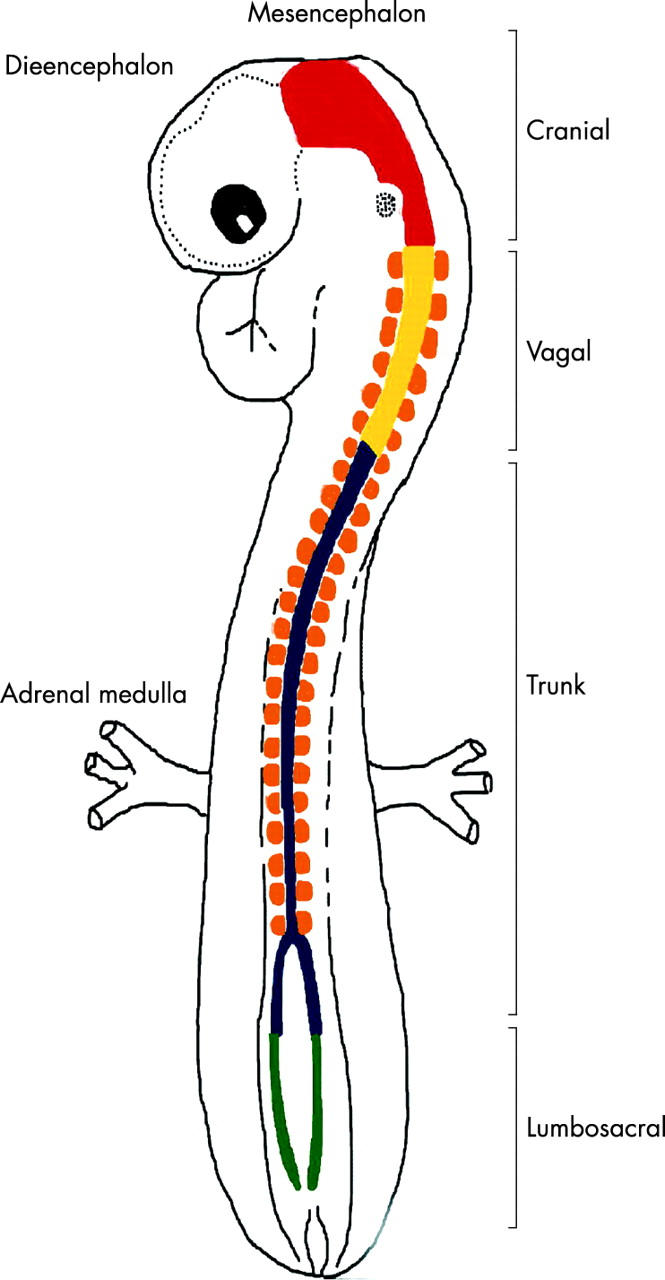

The neural crest represents one of the most dramatic examples of progenitor cell heterogeneity. 31 The neural crest can be divided into four regions along the anterior–posterior axis (cranial, vagal, trunk, and lumbosacral neural crest)(fig 3 ); these regions are based on the types of cells that they give rise to and the areas of the embryo that those cells populate. 32– 34 Like that of progenitor cells in the CNS, the fate of daughter cells generated by neural crest progenitor cells is determined by intrinsic and extrinsic cues along the anterior–posterior axis. 17, 32, 35– 38 Similarly, there is an order in which the different types of neural crest cells are produced; early cells follow a ventral pathway, and late cells follow a more dorsal pathway. Late generated cells in the trunk neural crest give rise to melanocytes, and these cells appear to undergo unidirectional changes in potential, such that they have only a limited capacity to generate sympathetic neurones.

Figure 3.

Spatial heterogeneity of the neural crest. The developing neural crest can be divided into four regions based on the migration of the neural crest progenitor cells and fates adopted by their daughter cells. For example, cranial neural crest cells give rise to sensory ganglia and facial cartilage; vagal neural crest and lumbosacral neural crest cells populate the enteric nervous system; and the trunk neural crest cells give rise to melanocytes, Schwann cells, and adrenal medulla. Neuroblastoma is believed to arise from trunk neural crest progenitor cells.

“It is not surprising that a tumour arising from a cell population that is highly migratory and simultaneously proliferates gives rise to the most deadly form of childhood cancer of the nervous system––neuroblastoma”

Progenitor cells in the CNS stop dividing before they migrate; however, one of the unique features of neural crest cells is that they continue to divide as they migrate. Some neural crest cells even continue to divide after they have adopted certain neuronal characteristics. Thus, it is not surprising that a tumour arising from a cell population that is highly migratory and simultaneously proliferates gives rise to the most deadly form of childhood cancer of the nervous system––neuroblastoma.

Neuroblastoma arises primarily in two locations—the adrenal medulla and paraspinal sympathetic ganglia—with approximately equal frequency. 2 Both of these tissues are derived from the trunk neural crest progenitor cells. Intrinsic properties or an extrinsic cue unique to the trunk region of the neural crest may make those cells more susceptible to tumorigenesis.

Molecular genetics

Exposure to environmental toxins is probably not a major source of neuroblastoma, 2 and it is probably not a cause of other childhood cancers of the nervous system either. The heritable form of neuroblastoma makes up 20% of cases, and the sporadic form comprises 80%. 39 Whether these two forms represent similar or disparate genetic alterations, epigenetic alterations, or both remains unknown. The heritable form presents at an earlier age; the median age at diagnosis of heritable neuroblastoma is 9 months, and that of sporadic neuroblastoma is 18 months. In addition, the heritable form of the disease is multifocal. These findings are consistent with the “two hit” mechanism of tumour initiation. 39 The first genetic alteration to be associated with neuroblastoma was the protooncogene NRAS. 40 However, that study was carried out on a neuroblastoma cell line, and subsequent analysis of primary tumours revealed that NRAS activation is a rare event in neuroblastoma transformation in humans. 41

To date, the best characterised genetic alteration in human neuroblastomas is amplification of the Myc related gene MYCN. 42 MAX forms a heterodimer with MYCN and activates the transcription of genes that are thought to promote cell cycle progression. Approximately 20% of patients with neuroblastoma in the USA exhibit amplification of the MYCN locus. 2 This chromosomal amplification is associated with rapid tumour progression and poor prognosis. Interestingly, sequential analysis of neuroblastomas from individual patients revealed that those who initially lack MYCN amplification rarely acquire it later during tumorigenesis. 43 This finding suggests that the MYCN pathway is a distinct pathway in approximately one fifth of neuroblastomas, and the other four fifths of tumours may arise from distinct genetic alterations. Some neuroblastomas have high amounts of MYCN protein without amplification of the 2p24 MYCN locus. 44 Whether this results from genetic or epigenetic change is not known, and neither has it been determined whether these tumours are as aggressive as those harbouring multiple copies of 2p24. It has also not yet been determined whether neural crest progenitor cell heterogeneity accounts for any part of the distinct pathways leading to neural crest transformation and neuroblastoma. For example, there may be a subset of progenitors at a given developmental stage or at a particular position in the trunk neural crest that are specifically dependent on MYCN for their normal proliferation and are more susceptible to transformation through MYCN amplification.

Alterations in several other loci have been associated with the heritable form of neuroblastoma, including 1p36 and 16p12–13. 2 In particular, loss of heterozygosity at 1p is strongly associated with MYCN amplification and poor prognosis. The relevant genes associated with these loci have not yet been identified, and neither has their relative contribution to neuroblastoma been determined. Along with amplification of MYCN at 2p24, DNA at other chromosomal locations, including 12q13 (MDM2) and 1p32 (MYCL), is amplified in neuroblastoma. 2 The relative contribution and independent prognostic value of these and other chromosomal regions, such as chromosome 17 trisomy, have yet to be determined for neuroblastoma.

Histopathological correlation with genetic changes

MYCN amplification is strongly correlated (31%) with the advanced stages of neuroblastoma (stages 3–4) and a poor three year outcome (30% probability of survival). Only 4% of patients with early stage neuroblastoma (stages 1–2) have MYCN amplification. Those patients without MYCN amplification have an excellent three year outcome (90% probability of survival). In addition to MYCN amplification, a few other general chromosomal alterations have been described. 2 Trisomy at 17q, the most common genetic alteration in neuroblastoma, may be associated with more aggressive tumours, but multivariate analysis has not yet established the prognostic relevance of amplification of the long arm of chromosome 17. Chromosome 1p deletion occurs in approximately 80% of otherwise diploid tumours. More specific studies have revealed that loss of 1p36 is not of prognostic value in terms of patient survival, but it is highly predictive of disease progression. 2 As mentioned above, NRAS activation is a rare event in neuroblastoma. However, HRAS activation is associated with a better outcome. 45 It has been proposed that the normal signalling cascade involving RAS and tyrosine kinase receptors leads to cell cycle exit, which is associated with differentiation during development of the neural crest. Thus, tumour cells with HRAS signalling may have a lower mitotic index and be less aggressive overall. Indeed, this is an excellent example of the importance of understanding the normal developmental pathway and the consequential genetics of the disease as it relates to prognosis. By showing that HRAS activation in neural crest progenitor cells induces differentiation and that this differentiation correlates with less aggressive neuroblastoma, investigators have revealed a pathway to target chemotherapy.

Genes that are often mutated in adult tumours such as p53, p16, p18, p27, and NF1 are rarely disrupted in neuroblastomas. 2 In some cell lines derived from neuroblastoma, mutations in these genes are more common, but this is probably the result of genetic changes in the immortal cell lines. This finding lends additional support to the idea that childhood tumours are fundamentally different from adult cancers, both in their cell of origin and possibly in the genetic lesions that lead to malignancy.

Xenograft mouse model of neuroblastoma

Orthotopic and heterotopic xenograft models in rodents, as a follow up to cell culture studies, have been the most widely used models to date for studies of drug efficacy. Several neuroblastoma cell lines are available for xenograft experiments, but they have several caveats that must be considered when designing xenograft experiments. As with NRAS and other genes that regulate proliferation and differentiation, mutations have probably occurred in the process of selecting cell lines in vitro. These additional mutations may mask or enhance the pathways that are altered in the original tumour and complicate the analysis of neuroblastoma xenografts. Even if the tumour cell lines resemble neuroblastoma in situ, it may be difficult to assess which stage of tumorigenesis or which progenitor cell of origin a particular cell line represents. The best xenograft studies rely on the use of multiple cell lines in orthotopic transplantation studies.

To prevent rejection of the human tumour cells in mice, experiments must be carried out in immunocompromised SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency disorder) or immunosuppressed animals. As expected, a side by side comparison of orthotopic (adrenal) neuroblastoma xenografts and heterotopic (subcutaneous) neuroblastoma xenografts in SCID mice demonstrated more relevant tumour biology by using the orthotopic models. 46 Interestingly, different cell lines metastasised to distinct sites, a finding that suggests inherently different properties of the tumour cell lines themselves. One of the drawbacks of this system is that it is time consuming; thus, it is a poor choice for screening large numbers of different antitumour compounds. Another limitation is that the stage of injection of the neuroblastoma cells is not developmentally appropriate—cells are typically injected into mature animals, whereas the disease occurs during development in children. The optimal xenograft model of neuroblastoma would be in an orthotopic site at an appropriate developmental stage to mimic the environment of endogenous neuroblastoma.

Transgenic mouse model of neuroblastoma

Because neuroblastoma in humans is associated with gross genomic alterations, including trisomy and regional chromosomal amplification, a transgenic approach was appropriate for generating a mouse model of this malignancy. To achieve this, Weiss and colleagues 14 generated a transgenic mouse with the tyrosine hydroxylase gene driving MYCN expression in the neural crest of developing mouse embryos. Tyrosine hydroxylase is expressed in the migrating cells of the neural crest and in the sympathetic ganglia and adrenal medulla arising from the trunk neural crest cells. 47 Although the precise timing of MYCN amplification in human neuroblastoma is not known, this transgenic mouse approach comes as close as possible to those cases of human neuroblastoma that have MYCN amplification. MYCN transgenic mice develop neuroblastoma that closely resembles the human disease. The site of tumours, tumour morphology, and subsequent gain and loss of chromosomal regions is remarkably similar to that seen in human neuroblastoma.

“The optimal xenograft model of neuroblastoma would be in an orthotopic site at an appropriate developmental stage to mimic the environment of endogenous neuroblastoma”

Despite all of the advantages of the transgenic MYCN model, the one drawback is that MYCN is expressed by many cells in the transgenic mouse, rather than just a single cell or a small number of cells, which is probably the case in neuroblastoma in humans. Such a large number of neural crest progenitor cells with altered MYCN expression may alter the developmental environment and lead to changes in neuroblastoma progression that do not faithfully recapitulate the human disease.

Targeted treatments

Large scale screening of children between the ages of 6 months and 1 year for neural crest derived tumours has increased the detection of neuroblastoma. Unfortunately, there has not been a concomitant reduction in the death rate as a result of early detection. 48, 49 Current treatments are clearly not sufficient to cure neuroblastoma, even when diagnosed early. This is partly because of our incomplete understanding of neural crest development and the genetic lesions that lead to deregulated proliferation and transformation of neural crest progenitor cells.

To date, the best molecular target for treatment for neuroblastoma is MYCN. 50 Although amplification occurs in only about 20% of neuroblastomas, it is correlated with a poor prognosis and thus has the greatest current potential for targeted antineuroblastoma treatment. Several approaches currently being studied focus on reducing amounts of MYCN mRNA by using antisense oligonucleotides or RNA. 51 In culture, different neuroblastoma cell lines respond differently to antisense treatment. Some undergo cell cycle arrest and initiate differentiation, whereas others execute apoptosis. To date, these phenomena have been studied only in cultured cells, and one of the most substantial clinical challenges for using MYCN antisense treatment is delivering the antisense molecules to the neuroblastoma cells in patients. Another potential obstacle to MYCN antisense treatment is the possibility of side effects resulting from MYCN downregulation in surrounding normal cells during development of the neural crest derived tissues.

An alternative approach to reduce the function of MYCN in neuroblastomas harbouring MYCN amplification has focused on designing small molecules that interfere with the formation of the MYC–MAX heterodimer, which is essential for MYCN mediated gene activation. 52 A high throughput screen of peptidomimetric libraries has led to the identification of several small molecules that may disrupt MYC–MAX dimerisation. Some of these small molecules were subsequently found to block MYC induced oncogenic transformation in fibroblast cultures. If small molecules that block MYC–MAX heterodimerisation bind the leucine zipper or helix–loop–helix domain of either protein, then it will be important to establish MYC–MAX specificity, because leucine zipper and helix–loop–helix domains are found on a variety of proteins that regulate several different processes during development.

Neuroblastoma summary

Neuroblastoma is derived from trunk neural crest progenitor cells, which are temporally and spatially heterogeneous and develop in diverse local environments. These cells are migratory, and the tumours that arise from the neural crest progenitor cells often metastasise to distant organs. The best studied genetic lesion in neuroblastoma is MYCN amplification. A transgenic mouse with MYCN amplification faithfully recapitulates many aspects of the human disease, and by combining high throughput cell culture, xenograft models, and this transgenic mouse model, researchers are now trying to target MYCN for antineuroblastoma treatment.

MEDULLOBLASTOMA

Cerebellar development

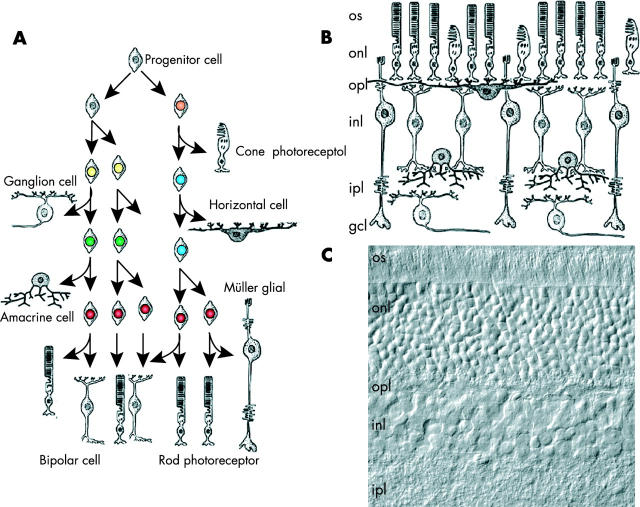

The postmitotic neurones and glia of the mature cerebellum are derived from two distinct progenitor cell populations, namely:(a) subventricular progenitor cells, which give rise to the Purkinje cells, Golgi neurones, and glial cells 53 ; and (b) a second, distinct pool of progenitor cells, which migrate rostrally from the rhombic lip, over the surface of the anlage, to form the external germinal layer (EGL) and give rise to the granule cells (fig 4 ). These cells continue to divide and expand until the EGL is approximately eight cells thick. Around the second postnatal week in the mouse, the granule cells stop dividing and migrate radially along Bergmann glia to form the internal granule cell layer and extend dendrites. Granule cells are the most abundant cell in the brain; in the mouse, they outnumber Purkinje cells 250 : 1, and in humans, this ratio is approximately 400 : 1. The ratio of granule cells to Purkinje cells is regulated by the period of proliferation of the different progenitor cell populations. The cells that give rise to the Purkinje cells in the subventricular matrix divide from embryonic day (E) 11 to E14 in the mouse, whereas those that give rise to the granule cells divide from E13 to postnatal day (P) 15. There is now considerable evidence that factors secreted by the Purkinje cells regulate the proliferation of the granule cell progenitors in the EGL. In particular, Purkinje cells secrete sonic hedgehog, and the granule cell progenitors express the hedgehog receptor patched. 54, 55 In this context, hedgehog signalling promotes proliferation of EGL cells. Although there is still a great deal to learn about the regulation of granule cell progenitor proliferation, it is apparent that there is heterogeneity in the cell cycle components that are used. For example, analysis of the single D-type cyclin mice revealed that EGL progenitors are uniquely dependent on cyclin D1 and D2, whereas the progenitors that give rise to the Purkinje cells are not. 56 Thus, these two progenitor cell populations rely on different components of the cell cycle machinery.

Figure 4.

The cerebellum is generated from two distinct progenitor cell populations. (A) The granule cells are produced from progenitor cells that migrate from the rhombic lip early during development. Once they arrive at the developing cerebellum, these cells proliferate extensively to produce the external germinal layer (EGL). (B) After this period of proliferation, the granule cell progenitors migrate along the processes of the Bergmann glia and begin to differentiate. Sonic hedgehog secreted by the Purkinje cells regulates the proliferation of the granule cell progenitors in the EGL, which express the hedgehog receptor, patched. Some forms of medulloblastoma are believed to arise from granule cell precursors that have sustained mutations in the hedgehog signalling pathway.

Clinical features

Medulloblastoma is the sixth most common malignancy in infants, accounting for 4% of all tumours. Approximately 3.5% of childhood tumours are medulloblastomas, 57, 58 and there are 350 new cases each year in the USA. The median age of presentation is 9 years. No race preference has been detected, but the tumour is slightly more common in boys than in girls (1.5 : 1). Boys tend to have a worse outcome. It is thought that medulloblastoma arises from EGL cells that have undergone genetic alterations in their pathway regulating cell cycle exit. 59, 60 Hart and Earle 61 hypothesised that primitive neuroectoderm is the source of medulloblastoma. Because medulloblastoma is thought to arise from a cell population that is committed to or at least biased to give rise to granule cells, one might expect a relatively uniform tumour presentation.

“It is thought that medulloblastoma arises from external germinal layer cells that have undergone genetic alterations in their pathway regulating cell cycle exit”

Most (80%) medulloblastomas are classified as the classic variant. 62 Classic medulloblastoma tumour cells are characterised by small symmetrical nuclei, and the cells are organised into layers or sheets of cells. The remaining 20% of medulloblastomas include desmoplastic, large cell, melanotic medulloblastoma, and medullomyoblastoma. Desmoplastic medulloblastoma tumours consist of clusters of cells surrounded by collagen rich tissue. These nodules of tumour cells exhibit characteristics of early differentiation based on morphological and molecular characteristics. Large cell medulloblastoma is characterised by a relatively high ratio of cytoplasm to nucleus, and these cells, like some other medulloblastoma cells, exhibit anaplasia. Melanotic medulloblastoma and medullomyoblastoma are exceptionally rare; melanotic medulloblastoma is characterised by the production of melanin, and medullomyoblastoma is characterised by the production of muscle specific proteins. Whether these variants of medulloblastoma reflect some intrinsic heterogeneity in the progenitor cell population that gave rise to the tumour or differences in the timing of tumour formation and spatial heterogeneity is unknown. The variants may also reflect distinct consequences of broad genetic changes, such as genomic instability. Nonetheless, classic medulloblastoma and tumours with nodularity and desmoplasia have similar clinical outcomes. The only clinical predictor of outcome is anaplasia—as anaplasia increases, the clinical outcome becomes worse.

Molecular genetics

There are both heritable and sporadic forms of medulloblastoma but most (95%) patients present as sporadic cases. The heritable forms include several well characterised syndromes that result from the inactivation of known genes. Li-Fraumeni syndrome is a result of p53 gene inactivation and often presents as medulloblastoma. Loss of part of chromosome 17 is the most common genetic lesion in medulloblastoma 62, 63 and may contribute to large cell/anaplastic forms of the disease. 64 Turcot syndrome is a result of APC (adenomatous polyposis coli) gene inactivation, and naevoid basal cell carcinoma, or Gorlin syndrome, is associated with a mutation in PTCH1. 65 Despite the relatively rare inactivation of PTCH1 in heritable medulloblastoma, the identification of the gene associated with Gorlin syndrome led to the analysis of sporadic medulloblastoma. It was found that the hedgehog pathway is inactivated in a variety of sporadic cases, as it is in heritable Gorlin syndrome. The discovery that hedgehog signalling is important for normal EGL progenitor cell proliferation during cerebellar development provides further evidence of the importance of this signalling pathway in medulloblastoma.

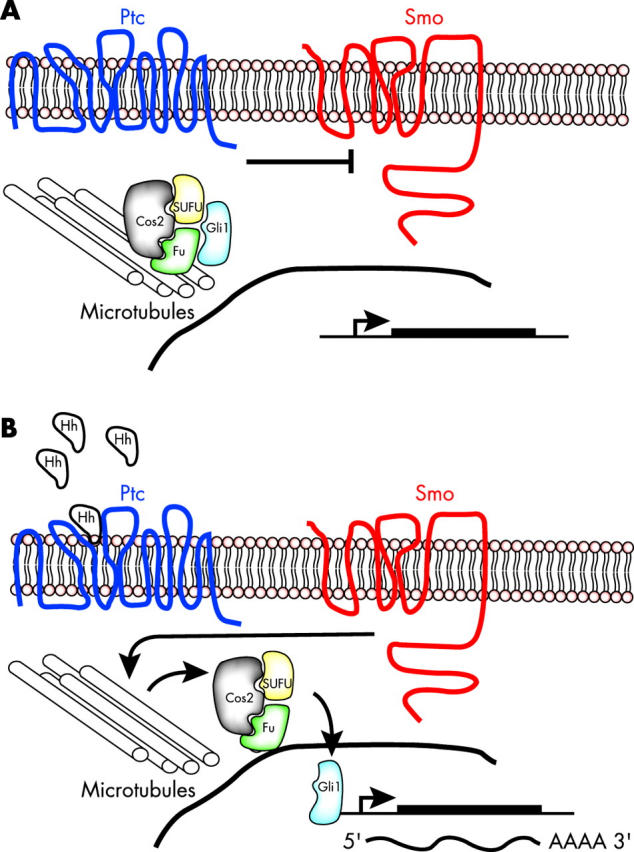

The genetic disruption of hedgehog signalling associated with medulloblastoma results in constitutive activation of downstream targets, such as Gli1, and deregulated proliferation of EGL progenitor cells. It is not surprising that the pathway, which is crucial for regulating normal EGL proliferation (fig 5 ), is also mutated in tumours of this tissue. The identification of a wide variety of mutated loci, all involved in hedgehog signalling, emphasises the importance of this pathway in the regulation of EGL progenitor cell proliferation. Currently, it is predicted that the hedgehog pathway is mutated in approximately 10–25% of medulloblastoma cases. 66 The real proportion of medulloblastomas with hedgehog pathway mutations may prove to be greater than current estimates as additional hedgehog pathway signalling components are analysed in these tumours.

Figure 5.

Hedgehog signalling leads to Gli1 activation. (A) In the absence of hedgehog (Hh) its receptor patched (Ptc) blocks smoothened (Smo), which leads to sequestering of the Gli1 transcription factor by a complex made up of Cos2, SUFU, Fu, and microtubules. Expression of Gli1 target genes is reduced in the absence of Hh signalling. (B) When hedgehog is present, Smo is no longer repressed and releases Gli1 to move into the nucleus and activate transcription of Gli1 target genes.

“The genetic disruption of hedgehog signalling associated with medulloblastoma results in constitutive activation of downstream targets, such as Gli1, and deregulated proliferation of external germinal layer progenitor cells”

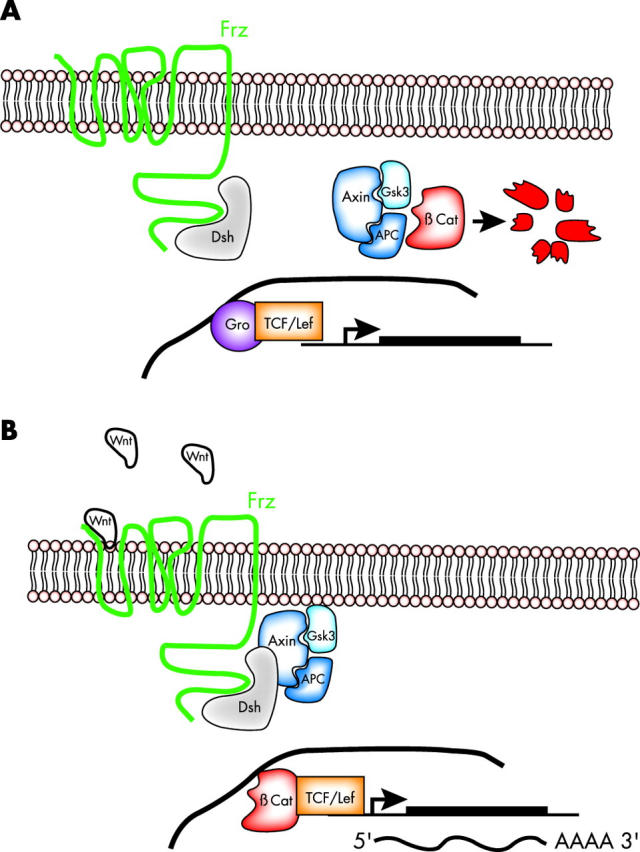

The association of medulloblastoma with Turcot syndrome led to the identification of mutations in the wingless–wnt pathway. 67, 68 In the cytoplasm, the β catenin transcriptional activator associates with the APC tumour suppressor protein, glycogen synthase kinase 3β(GSK-3β), and AXIN1 (fig 6 ). When associated, β catenin is phosphorylated and targeted for proteosomal degradation. When the wingless–wnt pathway is stimulated, GSK-3β kinase is blocked, β catenin is stabilised, and it can then move to the nucleus where it activates the TCF/LEF (T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor) transcriptional regulators. As a result, genes such as cyclin D1 and MYCC are upregulated, and cells progress through the cell cycle.

Figure 6.

Wnt signalling leads to β catenin stabilisation. (A) In the absence of Wnt signalling through its frizzled (Frz) receptor, the β catenin transcriptional regulator is degraded by a complex made up of AXIN1, GSK-3β, and APC. As a consequence, β catenin responsive genes are transcriptionally inactive, in part as a result of repression by the groucho (Gro) repressor. (B) When Wnt binds to the Frz receptor, degradation of β catenin is blocked;β catenin translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of β catenin responsive genes through the T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) family of transcriptional regulators.

Several mutations have been described that affect the wingless–wnt pathway, and such alterations may account for approximately 18–25% of all medulloblastoma cases based on those that express high amounts of β catenin. 67, 68 A detailed study of the roles of β catenin and the wnt–wingless pathway in cerebellar development has not yet been carried out. β Catenin knockout mice failed to mature to the stage at which the proliferation of granule cell progenitors could be measured. 69 Similar conditional β catenin knockout mice generated using a Wnt-1 Cre mouse failed to form a cerebellum by E18, so the later stages of cerebellar development could not be studied. 70 Development did not progress far enough in the conditional knockout mice to assess the role of β catenin in granule progenitor cell proliferation.

Histopathological correlation with genetic changes

There are currently only a few known molecular genetic alterations that are associated with the histopathological classification of medulloblastoma. 62 Two different genetic features, MYCC amplification and isochromosome 17q, are more often found in anaplastic and large cell medulloblastoma than in other forms of the disease. Desmoplastic medulloblastomas exhibit a high occurrence (30–40%) of mutations involving the hedgehog pathway genes such as PTCH. At this time, there is not a strong correlation between wnt–wingless signalling pathway mutations and the histopathological grade of medulloblastoma.

Xenograft mouse model

Medulloblastoma xenograft models present many of the same challenges that neuroblastoma xenograft models do. For example, the tumour cell lines used for transplantation need faithfully to recapitulate the genetic, morphological, and clinical features of human medulloblastoma. In addition, we need to discern whether different tumour cell lines represent changes in different genetic signals such as hedgehog or β catenin, and whether they represent different histopathological variants including the classic form, the nodular form, the desmoplastic form, and the large cell/anaplastic form.

Medulloblastoma cell lines do not engraft well in heterotrophic mouse xenograft models. 71 Even when matrix components such as matrigel are included with the inocula to improve engraftment rates, the cells clearly do not experience the same environment as the tumour in vivo. 72 For example, there is no blood–brain barrier, and the complex events that take place in a developing cerebellum are quite different from those that occur in an adult heterotrophic site (flank) in a SCID mouse. Although orthotopic xenografts of medulloblastoma more faithfully recapitulate the human disease, monitoring tumour growth is more challenging when intracranial sites of injection are chosen. Recent work using magnetic resonance imaging to monitor mouse xenograft models of medulloblastoma has largely circumvented these challenges and provided exceptional xenograft models of this disease. 73 The only factor that is not consistent with the human disease is the developmental stage of the mice at the time of injection.

Current xenograft models rely on mature SCID mice rather than those at a developmental stage that is analogous to the developmental stage of tumour initiation in humans. As discussed above, this is crucial, because the environment in the developing cerebellum is very different from that in the mature tissue. To improve current medulloblastoma models, human cell lines could be injected at birth into the developing cerebellum to mimic the human disease. An added advantage of this approach is that wild-type mice rather than SCID mice could be used, because newborn mice are immunonaive for the first 24 to 48 hours after birth.

Knockout mouse model of medulloblastoma

Some of the most promising mouse models of medulloblastoma that have been generated come from knockout mice carrying targeted deletions of genes in the hedgehog pathway or genes that lead to disruptions of hedgehog signalling in granule cell progenitors. 74 For example, Ptch heterozygous mice develop medulloblastoma at a rate of approximately 8% up to 12 weeks of age and up to 30% between 12 and 25 weeks of age, 15 and p53 mutations enhance the frequency of medulloblastoma in Ptch heterozygous mice. 75 Although p53 mutations are rare in human medulloblastoma, the inactivation of p53 may cause genomic instability and subsequent genetic alterations that lead to transformation. Consistent with this idea, deletion of p53 and Rb in the developing brain, 76 deletion of p53 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (Parp), 77 or deletion of p53 and DNA ligase IV (Lig4) 78 also resulted in medulloblastoma. The common feature of these seemingly disparate knockout mice is that all of the mutations lead to genomic instability and Gli1 activation. 66 Taken together, these studies suggest that genomic instability that results from deletion of p53 and other genes in the developing cerebellum can lead to medulloblastoma by disrupting the hedgehog pathway.

Although the mechanism of Gli1 activation may not be the same in these mouse models as it is in human tumour cells, the animal studies lend support to the importance of the hedgehog pathway in medulloblastoma. Moreover, targeting Gli1 for the treatment of medulloblastoma may be an efficient means to treat this childhood tumour, even if the initiating event (PTCH, p53, PARP, RB, or LIG4 mutation) differs among individuals, as it does in the mouse.

The data on medulloblastoma are in sharp contrast to those concerning MYCN amplification in neuroblastoma. Early stage neuroblastomas that do not have MYCN amplification do not acquire mutations in this gene later as a result of genomic instability or other mechanisms. At least in the mouse models, early medulloblastomas that do not have hedgehog signalling disruptions can acquire such mutations via genomic instability. It will be interesting to determine whether similar conditional inactivation of components of the β catenin pathway will also provide clues about medulloblastoma formation and suggest targets for treatment such as the TCF/LEF transcription factors.

“Some of the most promising mouse models of medulloblastoma that have been generated come from knockout mice carrying targeted deletions of genes in the hedgehog pathway or genes that lead to disruptions of hedgehog signalling in granule cell progenitors”

One important factor that should be considered with regard to the medulloblastoma mouse models is that even if the genetic lesions are exactly the same as those in the human tumours (for example, PTCH), every cell in the Ptch+/− mouse or at least in the tissue of interest in the conditional knockout mouse carries the genetic mutation. This is dramatically different from human cases of sporadic medulloblastoma, which probably arise from individual granule cell progenitors that have undergone genetic alterations. Thus, an ideal mouse model would rely on gene inactivation in single granule cell progenitors during development at a stage and location similar to the time and place of gene inactivation during tumorigenesis in the cerebellum of children.

Targeted treatments

Findings from studies of mouse genetics and human mutations suggest that hedgehog signalling in general and Gli1 activity in particular are good targets for anticancer treatments in medulloblastoma. As with the MYCN targeted treatments in neuroblastoma, one can imagine a variety of approaches for downregulating the Gli1 gene in medulloblastoma. First, Gli1 could be targeted by antisense RNA or antisense oligonucleotides. Alternatively, small molecules may be identified that bind to Gli1 and block its function. As with MYCN treatment, the primary challenge of identifying potential small molecules that block Gli1 protein function in medulloblastoma cells is establishing organ and protein target specificity. Hedgehog signalling is used in a variety of tissues during development and adulthood; thus, broad inactivation of this signalling pathway in non-affected tissues could be detrimental to normal physiology. Nonetheless, a thorough understanding of the hedgehog pathway was instrumental in identifying Gli as a chemotherapeutic target.

If researchers had attempted to target the other genes thought to be involved in medulloblastoma formation without knowing that Gli1 is the downstream target, the results would probably have been disappointing. For example, targeting p53, Parp, or Lig4 in a mouse model may help to establish genomic stability and prevent tumour formation, but if the effective target is not the mechanism of tumorigenesis in humans, then it probably will not translate to the clinic. Targeting Gli1 may translate with high efficacy to the clinic, even if the upstream genetic events are dissimilar in humans and mice, because in both humans and mice, Gli1 activation is a crucial event in a subset of medulloblastomas.

Medulloblastoma summary

Medulloblastoma is an excellent example of how basic research on the developmental neurobiology of a mouse model combined with studies of human tumours can identify a common target, hedgehog pathway–Gli1, which may prove useful for targeted anticancer treatments. The hedgehog pathway is crucial for regulating proliferation of EGL progenitor cells in the developing cerebellum, and the normal regulation of hedgehog signalling is disrupted in medulloblastoma. Wnt–wingless signalling is also mutated in medulloblastoma, and it is believed that wnt–wingless signalling is an essential regulator of EGL progenitor cell proliferation during development. These two pathways are frequently mutated in medulloblastoma; thus, EGL progenitor cells exhibit deregulated proliferation, which eventually leads to malignant transformation.

RETINOBLASTOMA

Retinal development

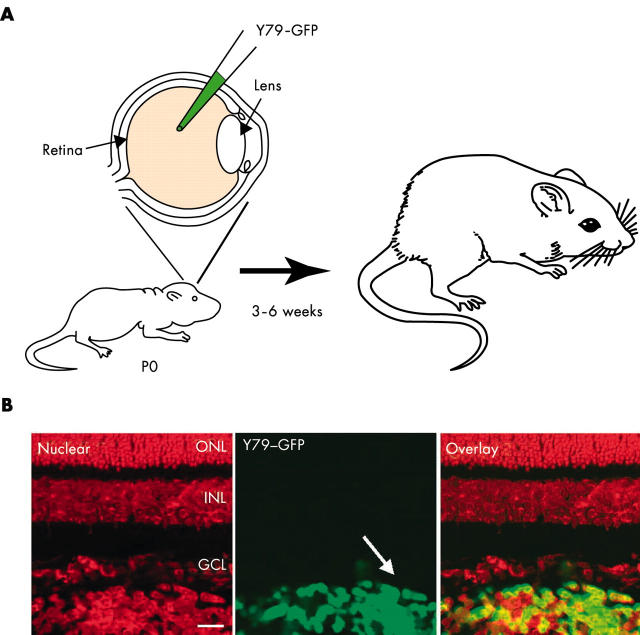

Early during brain development, the optic cup forms as an outcropping of the forebrain. The retinal progenitor cells that make up the optic cup divide and give rise to the seven classes of retinal neurones and glia over the course of development in an evolutionarily conserved order. Importantly, the different cell types are generated from multipotent retinal progenitor cells, and it has been proposed that retinal progenitor cells undergo unidirectional changes in competence during development. 6 That is, at a given stage of development, retinal progenitor cells are competent to give rise only to a subset of the postmitotic cell types generated at that developmental stage (fig 7 ). This model implies that intrinsic changes occur in the retinal progenitor cells during development. It has also been shown that extrinsic cues regulate retinal progenitor cell development. Thus, the balance between intrinsic and extrinsic signals ultimately dictates the precise generation of the different cell types in the retina. 6 This general scheme (that is, the generation of neural and glial cell types from multipotent progenitor cells in a characteristic order) is common throughout the nervous system. As with other regions of the developing nervous system, not only are temporal changes occurring in retinal progenitor cells during histogenesis, but also spatial heterogeneity is taking place. 5

Figure 7.

Retinal neurones and glia are generated in an evolutionarily conserved order during development. (A) The seven classes of retinal cell types (rods, cones, bipolar cells, amacrine cells, horizontal cells, ganglion cells, and Müller glia) are generated in a precise order during development. As in other regions of the nervous system, retinal progenitor cells are thought to undergo unidirectional changes in competence to give rise to the different retinal cell types. Retinoblastoma is thought to arise from a retinal progenitor cell, and depending on when during development the second RB allele is mutated, the tumour may express markers of different retinal cell types. Importantly, the timing of the exit from the cell cycle is also crucial for normal retinal development, because the different classes of cell types are produced in distinct ratios. If too many cells exit the cell cycle during the early stage of development, then the proportion of early born cell types increases at the expense of that of late born cell types. (B) For example, the ratio of rods to horizontal cells in the mouse retina is approximately 140 : 1. (C) A differential interference contrast image of mouse retinal section showing the outer nuclear layer and the inner nuclear layer. gcl, ganglion cell layer; inl, inner nuclear layer; ipl, inner plexiform layer; onl, outer nuclear layer; opl, outer plexiform layer; os, outer segments.

Clinical features

Retinoblastoma is a childhood tumour of the neural retina; 95% of cases are diagnosed before 5 years of age and usually within the 1st year of life. 79 Retinoblastoma comprises 11% of all cancers in infants, making it the third most common childhood cancer after neuroblastoma and leukaemia. In children younger than 15 years, retinoblastoma accounts for 3% of all cancers. Each year, approximately 300 new cases of retinoblastoma are diagnosed in the USA. Like medulloblastoma and neuroblastoma, retinoblastoma is believed to arise from progenitor cells during development. There are several lines of evidence for this. First, inactivation of the RB gene (see below) is believed to occur during DNA replication, which primarily occurs in dividing retinal progenitor cells during development. Second, retinal tumours initiate during fetal development, when retinal progenitor cells are actively dividing. 80, 81 Moreover, this tumour never presents in adolescents or adults, a finding that suggests that once the retinal neurones and glia differentiate they are not susceptible to malignant transformation. Third, molecular analysis of primary retinal tumours revealed a wide variety of differentiation markers, including glial and neuronal markers. 79 Indeed, marker expression for every retinal cell type has been reported in retinoblastoma. If a retinal progenitor cell sustains a mutation in RB at a particular time during development and initiates the process of becoming a tumour, then some of the differentiation markers expressed in cells normally made at that time during development would probably be expressed in the tumour. Some tumours sustain RB mutations early, and others sustain them much later during development; therefore, it makes sense that different tumours express different cohorts of differentiation markers. Thus, rather than pointing to a differentiated cell of origin, analysis of differentiation markers in retinoblastomas has lent support to the idea that the cell of origin is a multipotent retinal progenitor.

Metastatic retinoblastoma is one of the most deadly of childhood tumours. If this disease metastasises beyond the eye, the probability of survival is only 5–10%. 82– 84 However, if diagnosed early, enucleation can save 90–95% of patients. Some children present with unilateral retinoblastoma with a small number of tumour foci, whereas others present with multifocal bilateral retinoblastoma. These different forms reflect the molecular genetics of retinoblastoma gene inactivation (see below). 79, 85 Paediatric screening followed by enucleation is the current approach to unilateral retinoblastoma. Current efforts for treatment are focused on saving vision in patients with bilateral retinoblastoma. 86

Molecular genetics

As with the other childhood tumours of the nervous system, there are sporadic and heritable forms of retinoblastoma. 74 However, unlike neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma, in which the heritable form is a relatively small proportion of the total number of cases, approximately 40% of children with retinoblastoma exhibit the heritable/bilateral form. 84 Unilateral and bilateral retinoblastoma result from inactivation of the same gene, RB1. 79 The difference in tumour initiation is believed to reflect the inheritance of the first RB1 mutation. When children inherit a defective copy of RB1 from one parent, every cell in their body is heterozygous for that lesion. All that is required for a retinal tumour to develop is the inactivation of the second RB1 allele during DNA replication in retinal progenitor cells. In sporadic retinoblastomas, the child does not inherit a defective copy of RB1. For a tumour to form in the retinae of these children, both copies of RB1 must be inactivated in the same cell. The likelihood of both RB1 alleles being inactivated by random mutation in a single retinal progenitor cell is much lower than that of the inactivation of a single RB1 allele in children who have inherited one defective copy of RB1.

“Efforts are under way to isolate new retinoblastoma cell lines, which should more faithfully recapitulate the genetic alterations that occur in human tumours”

Most, if not all, retinoblastomas arise from the inactivation of RB1; however, very little is known about the secondary genetic lesions that follow RB1 inactivation. The p53 gene has been studied the most extensively, but like neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma, retinoblastoma rarely involves mutations at this locus. 87

Histopathological correlation with genetic changes

Two histopathological features of retinoblastoma have been described. Flexner-Wintersteiner and Homer-Wright rosettes (fig 1B ) have been proposed to reflect partially differentiated retinoblastoma cells. 88, 89 Yet, in general, retinoblastoma cells are small undifferentiated cells with high mitotic indices. These cells form rings of viable cells surrounding the vitreoretinal vasculature in the vitreous humour that has been co-opted from the retinal surface. Depending on the extent of vascularisation, there may be necrotic, calcified debris in the vitreous humour from dead tumour cells that were displaced from the vasculature as the tumour cells divided. The other histopathological feature of retinoblastoma is vitreal seeds (fig 1B ), which are small clusters of tumour cells free floating in the vitreous. 90 Vitreal seeds present one of the major challenges of treating retinoblastoma, because they can form new tumour foci after chemotherapy is complete. For metastatic retinoblastoma, tumour cell invasion usually occurs at the optic nerve. None of these histological features has been correlated with molecular alterations because of the paucity of molecular analysis of the genetic events downstream of RB1 inactivation.

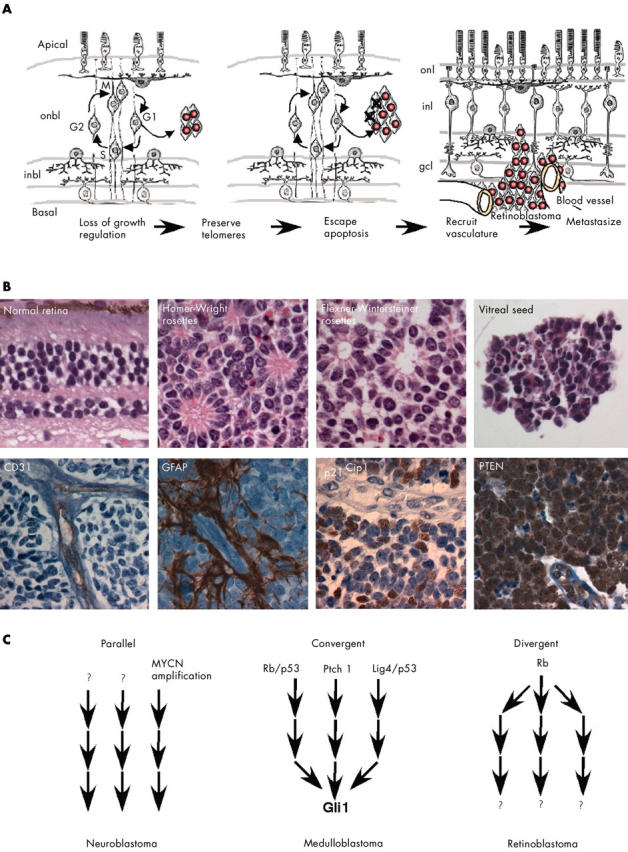

Xenograft mouse model of retinoblastoma

There are currently two widely used retinoblastoma cell lines available from the ATCC, Y79 and Weri1. These cell lines have been cultured for decades and have probably undergone genetic changes since their original isolation. Thus, it will be important to isolate new cell lines from patients and repeat any xenograft experiments with the fresh isolates to verify the data from Y79 and Weri1 cells. Until recently, the only xenograft model of retinoblastoma involved injecting Y79 or Weri1 cells into the eyes of adult immunocompromised mice. The intraocular environment of the adult eye is dramatically different to that of the developing eye; thus, we sought to generate a xenograft model that more faithfully recapitulated the human disease. To achieve this, we injected the Y79 or Weri1 cells into the eyes of newborn rats (fig 8 ). Immunosuppression was not required, because newborn rats are immunonaive and do not reject the human cells. Moreover, this developmental stage is more appropriate for the timing during human development when the tumours are likely to form. The xenografted tumour cells (1000 cells/eye) filled the vitreous humour within two weeks and exhibited many of the features of the human disease, including vascular reorganisation, invasion at the optic nerve, and calcification characteristic of cell death in regions of the vitreous humour where the exchange of oxygen and nutrients is limited. To follow their growth and invasion, we labelled the engrafted cells with a green fluorescent protein reporter gene (fig 8 ). We are currently using this xenograft system to study several new chemotherapeutic treatments. Although the treatments we are testing are not targeted ones (see below), they may improve the rate of vision preservation in patients with bilateral retinoblastoma. Efforts are under way to isolate new retinoblastoma cell lines, which should more faithfully recapitulate the genetic alterations that occur in human tumours.

Figure 8.

Developmentally appropriate orthotopic retinoblastoma xenograft model. (A) Cultured retinoblastoma cells labelled with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene were injected into the vitreous humour of newborn rats (1000 cells/eye). Two weeks later, the animals were treated with a chemotherapeutic drug, and three to six weeks later the effects were analysed by scoring the proportion of GFP positive cells in the vitreous humour. (B) The transplanted retinoblastoma cells are easily distinguished from the normal retinal cells by their green fluorescence. The red fluorescence is a nuclear counterstain.

Clonal inactivation of the RB family

The orthotopic, developmentally appropriate xenograft model described above is optimal for testing new chemotherapeutic treatment protocols, because the site of injection, stage of development, and histological features are remarkably similar to those of the human disease. However, despite these advantages, xenografts are somewhat artificial in that a homogenous population of cells that is already transformed is placed into a naive environment. In humans, developing cancer cells interact with the surrounding tissue, resulting in a heterogeneous population of cells and a tumour with spatial heterogeneity. Ideally, a high throughput screen involving a genetic model of retinoblastoma that faithfully recapitulates the human disease would be a better system for developing new treatment protocols.

RB1 was the first tumour suppressor gene cloned in humans 91, 92 and the first tumour suppressor knocked out in mice. 93– 95 It was expected that Rb heterozygous mice would phenocopy humans and present with bilateral retinoblastoma. Interestingly, Rb+/− mice do not develop retinoblastoma. They do, however, present with pituitary tumours, a finding that indicates that Rb is a tumour suppressor in mice. Subsequent studies revealed that the human RB1 gene rescues the embryonic lethality of Rb deficient embryos; thus, the difference between humans and mice is not a reflection of the primary structure of Rb in these two species. To explain the lack of intraocular malignancy in Rb+/− mice, researchers proposed that there may be redundancy between Rb and the other Rb family members, p107 and p130, in the developing retina. To date, this theory has not been directly verified, but there are a few intriguing clues from genetic studies in mice. Chimaeric mice made from Rb deficient cells do not develop retinoblastoma; therefore, Rb inactivation alone is not sufficient for tumour formation. 96 Tumours form when Rb, p107, and p53 are inactivated, but whether p107, p53, or both genes must be inactivated for retinoblastoma to form in the mouse retina remains unknown. 97 In addition, whether these effects are cell autonomous or not is also unknown. A variety of non-cell autonomous effects have been reported for Rb in the mouse, so it is possible that some of the contributions of Rb, p107, or p53 are non-cell autonomous.

Several different transgenic mouse models have been developed that express oncogenes such as the T antigen from SV40 virus or E1A from adenovirus, but these experiments have not substantially advanced our understanding of the genetics of retinoblastoma in the mouse. 98– 100 This is because oncogenes are promiscuous and can bind and inactivate all of the Rb family members and other proteins that regulate proliferation and apoptosis. In addition, these mice do not advance our understanding of the cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous contributions of the different genes that may contribute to tumorigenesis in the mouse, because the expression patterns of the various transgenes are broad and poorly characterised.

Rather than use transgenic approaches, we used a series of retroviral vectors to induce changes in single retinal progenitor cells in vivo. We started with replication incompetent retroviruses that can infect dividing retinal progenitor cells only. These vectors have an internal ribosome entry site and a reporter gene, so we can identify the infected cells. Then, a gene of interest is cloned into the viral vector, and a stock is made. The stock is then injected into the eyes of newborn mice or rats, and several weeks later, the clones of cells that originated from individual infected retinal progenitor cells are analysed. By diluting the virus, we can achieve a small number of tumour foci (one to five foci) in each retina. The advantage of this system is that tumours arise from individual retinal progenitor cells rather than from a large cell population, and we can begin to study the cell autonomy of these effects. When combined with the xenograft model, these studies provide both a complimentary model for drug testing and reagents to begin to identify the downstream mutational events that lead from Rb inactivation to tumour formation.

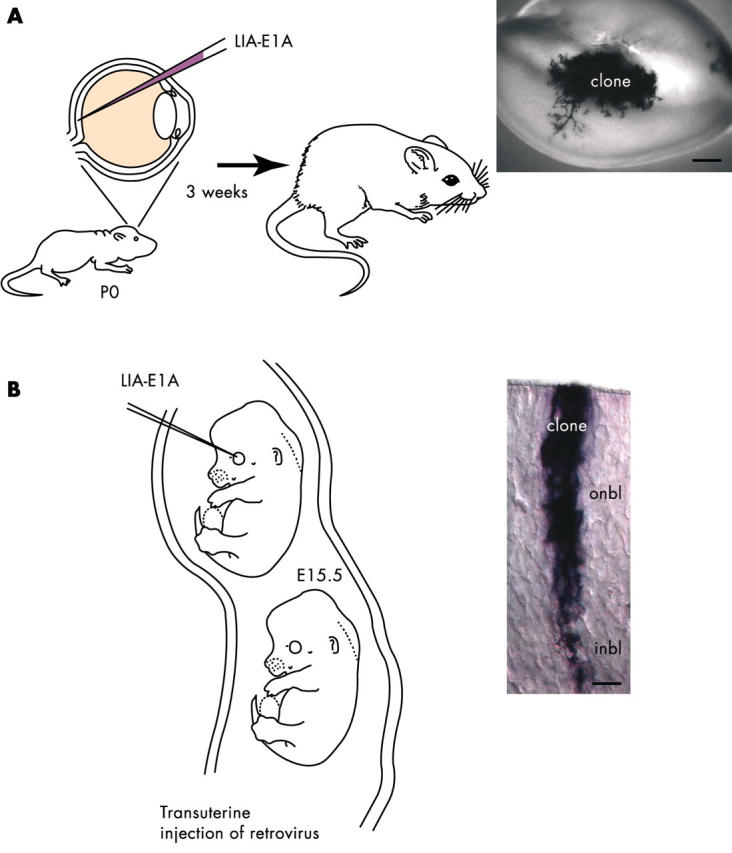

In the first series of experiments, we cloned E1A 13S cDNA into our retroviral vectors. After infection of P0 retinal progenitor cells in vivo, we observed clonal hyperplasia. Interestingly, no tumours formed in these animals as much as eight weeks after infection. As discussed above, there are some data to suggest that for retinoblastoma to form in the mouse, the p53 gene must be inactivated. To test this directly, we injected the same E1A virus into the eyes of newborn p53 deficient mice. Within three weeks, at an infection rate of one to five clones/retina, retinoblastoma formed (fig 9 ). This system has the distinct advantage over transgenic models of retinoblastoma in that tumours arise from a single cell rather than a large pool of progenitors of differentiated neurones.

Figure 9.

Clonal retinoblastoma in the mouse retina after retroviral infection. (A) To inactivate all of the Rb family members in an individual retinal progenitor cell in vivo, we injected a retrovirus carrying the E1A oncogene and an alkaline phosphatase reporter gene into the eyes of newborn mice carrying a targeted deletion of the p53 tumour suppressor gene. The infected retinal progenitor cells gave rise to tumours after three weeks. This model will serve as a complement to the xenograft model described in fig 8 . (B) To explore the developmental susceptibility of retinal progenitor cells to transformation, we used a novel transuterine injection procedure to target the retinae of embryonic day (E) 15.5 mouse embryos for retroviral infection. By comparing the incidence of tumour formation after infection at E15.5 with that after infection at postnatal day (P) 0, we hope to determine whether embryonic retinal progenitor cells are more or less susceptible to transformation.

As mentioned earlier, retinal progenitors are temporally and spatially heterogeneous. Therefore, it is possible that some retinal progenitors may be more or less susceptible to transformation. To address this question, we initially developed a procedure for injecting retroviruses into the eyes of embryonic mice in utero. Previously, it was technically too difficult to perform in utero viral injections, because few animals survived after birth. Using this approach, we are now testing the susceptibility of early retinal progenitor cells to E1A mediated transformation in different genetic backgrounds.

Although E1A is useful for inducing tumours from individual retinal progenitor cells in the developing retina, it is an oncogene that binds to all of the Rb family members, in addition to other proteins such as p300. To dissect the molecular pathway leading to retinal tumorigenesis in the developing mouse retina more precisely, we have developed a retrovirus based system that can inactivate specific genes in individual retinal progenitor cells. Specifically, we have generated and tested a conditional knockout retrovirus encoding the Cre recombinase. By infecting retinal progenitor cells in mice carrying the LoxP recombination site, we can selectively inactivate genes in individual retinal progenitor cells in vivo. Conditional knockout mice are now available for both Rb and p53, and by crossing these mice with p107 knockout mice, we can attempt to discern precisely which of these genes are important for the generation of retinal tumours in mice in vivo. Moreover, because 10 000 to 100 000 uninfected cells surround the individual clones of cells infected with the retroviruses, it is reasonable to assume that any changes in proliferation or tumorigenesis are cell autonomous.

Targeted treatments

There are currently no targeted treatments for retinoblastoma, because very little is known about the downstream genetic events that lead to malignant transformation in retinal progenitor cells. We hope that by using the mouse genetic system combined with molecular analyses of primary and cultured human retinal tumours, we will be able to identify potential candidates for targeted anticancer treatment in retinoblastoma.

Retinoblastoma summary

Despite the early discoveries involving the initiating molecular genetic changes that lead to retinoblastoma, we know very little about the subsequent genetic or epigenetic changes that occur in these tumour cells as they progress from preneoplastic lesion to metastatic cancer. This is the result, in part, of the lack of a mouse model that faithfully recapitulates the human disease. Transgenic mice ectopically expressing oncogenes in the retina have been of limited use for the study of retinoblastoma, because the transgene is expressed in a large number of cells, leading to massive hyperproliferation rather than focal transformation. The recently developed retroviral system that we have used to induce retinoblastoma results in the focal formation of tumours that are much more similar to human retinoblastoma. The limitation of the current retroviral system is that it relies on the E1A oncogene to inactivate the Rb family. A more elegant approach would rely on the inactivation of individual Rb family members in individual retinal progenitor cells by using a retrovirus encoding Cre recombinase and RbLox mice. This system is currently being tested.

“To dissect the molecular pathway leading to retinal tumorigenesis in the developing mouse retina more precisely, we have developed a retrovirus based system that can inactivate specific genes in individual retinal progenitor cells”

Recent advances in rodent xenograft models have led to a developmentally appropriate orthotopic xenograft model of retinoblastoma. We are currently using this system to study new chemotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of bilateral retinoblastoma at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. However, these xenografts rely on retinoblastoma cell lines that were isolated decades ago, and efforts are under way to generate new tumour cell lines that have experienced limited time in culture and fewer opportunities for genetic alterations.

DISCUSSION

Childhood medulloblastomas (350 cases each year), retinoblastomas (300 cases each year), and neuroblastomas (700 cases each year) comprise a large portion of all childhood malignancies diagnosed in the USA each year. In infants, the combination of these three malignancies makes up 47% of all tumours, yet they are rare compared with the annual number of new cases of adult tumours. Not only are these childhood malignancies rare, but they are also difficult to study because of the complexity of the environment in which they form. Because the number of new paediatric patients with tumours of the nervous system is so small each year, corporate investment in targeted drug treatments for these diseases is limited. However, some of the genes and pathways involved in tumorigenesis of the developing nervous system are mutated in more prevalent adult cancers, and children with these developmental tumours can benefit from drugs targeted for the adult forms of cancer.

Model systems developed in mice play an important role in research focused on improving our understanding and treatment of childhood tumours of the nervous system. First, studies on mice have provided us with the knowledge of the development of the neural crest, cerebellum, and retina that is essential for understanding neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, and retinoblastoma, respectively. For example, the discovery that trunk neural crest cells give rise to the adrenal medulla and paraspinal sympathetic ganglia where neuroblastomas originate has provided some valuable clues about the potential of different neural crest progenitor cell populations to undergo transformation. Second, genetically engineered mice are an ideal experimental system in which to begin testing the contribution of different genes to tumorigenesis in these tissues. The detection of medulloblastoma in Ptch1 deficient mice helped to confirm the involvement of hedgehog signalling in some forms of this cancer. Third, using xenograft models or transgenic/knockout strategies, several valuable mouse models have been characterised for testing new treatment for these devastating childhood tumours of the nervous system. A new xenograft model of retinoblastoma that is developmentally appropriate is being used to improve treatment of this cancer. In addition, in vivo retroviral infection of murine retinal progenitor cells has led to the development of a mouse model of retinoblastoma in which tumours arise from a small number of infected retinal progenitor cells, thereby faithfully recapitulating the human disease.

Take home messages .

To advance our understanding of tumours of the developing nervous system, we must first understand the molecular genetic pathways that are important during normal development

The cells of origin for many childhood tumours of the nervous system are multipotent proliferating progenitor cells

Rodent models are an important tool for advancing our understanding of normal and aberrant nervous system development

By combining different types of animal models of cancer, including xenografts, transgenics, and gene knockouts, we can produce the most complete picture of treatment efficacy

Using in vivo retroviral infection approaches, researchers can now generate focal, clonal tumours in the developing nervous system

Despite these recent advances in the use of mouse models to study and treat childhood tumours of the nervous system, such models must be complemented by research on human tumours. In particular, retrospective studies using tissue arrays to study protein expression, RNA expression, and genetic amplifications/deletions can be complemented with microarray analysis of primary tumours and characterisation of freshly isolated cell lines derived from tumours. By bringing together results from model systems with those from traditional molecular analyses of pathological specimens, researchers and clinicians will be able to apply targeted anticancer treatments with greater efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

APC, adenomatous polyposis coli

CNS, central nervous system

E, embryonic day

EGL, external germinal layer

GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β

Lig4, DNA ligase IV

P, postnatal day

PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency disorder

TCF/LEF, T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor

REFERENCES

- 1. Hahn WC, Weinberg RA. Modelling the molecular circuitry of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2:331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brodeur GM. Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer 2003;3:203–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Basch ML, Selleck MA, Bronner-Fraser M, et al. Timing and competence of neural crest formation. Dev Neurosci 2000;22:217–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cepko CL, Austin CP, Yang X, et al. Cell fate determination in the vertebrate retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dyer MA, Cepko CL. Regulating proliferation during retinal development. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001;2:333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001;2:109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dreyfus CF. Neurotransmitters and neurotrophins collaborate to influence brain development. Perspect Dev Neurobiol 1998;5:389–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sommer L. Context-dependent regulation of fate decisions in multipotent progenitor cells of the peripheral nervous system. Cell Tissue Res 2001;305:211–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Castro F. Chemotropic molecules: guides for axonal pathfinding and cell migration during CNS development. News in Physiological Science 2003;18:130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldman JE. Lineage, migration, and fate determination of postnatal subventricular zone cells in the mammalian CNS. J Neurooncol 1995;24:61–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldman JE, Zerlin M, Newman S, et al. Fate determination and migration of progenitors in the postnatal mammalian CNS. Dev Neurosci 1997;19:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Naruse I, Keino H. Apoptosis in the developing CNS. Prog Neurobiol 1995;47:135–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cleaver O, Melton DA. Endothelial signaling during development. Nat Med 2003;9:661–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weiss WA, Aldape K, Mohapatra G, et al. Targeted expression of MYCN causes neuroblastoma in transgenic mice. EMBO J 1997;16:2985–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodrich LV, Milenkovic L, Higgins KM, et al. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science 1997;277:1109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tropepe V, Coles BL, Ciasson BJ, et al. Retinal stem cells in the adult mammalian eye. Science 2000;287:2032–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bronner-Fraser M. Molecular analysis of neural crest formation. J Physiol Paris 2002;96:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McConnell SK. Plasticity and commitment in the developing cerebral cortex. Prog Brain Res 1995;105:129–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garcia-Castro M, Bronner-Fraser M. Induction and differentiation of the neural crest. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1999;11:695–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. LaBonne C, Bronner-Fraser M. Molecular mechanisms of neural crest formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1999;15:81–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fischer AJ, Reh TA. Muller glia are a potential source of neural regeneration in the postnatal chicken retina. Nat Neurosci 2001;4:247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blau HM, Brazelton TR, Wimann JM. The evolving concept of a stem cell: entity or function? Cell 2001;105:829–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]