Abstract

Aims: It has previously been shown that the low necropsy request rate at the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI) in Jamaica (35.3%) results primarily from clinicians’ confidence in clinical diagnoses and laboratory investigations. This study aimed to determine the rates of discrepancy between clinical and necropsy diagnoses at the UHWI, because many previous studies from other institutions have shown persistent high rates of discrepancy, despite advances in medical investigative technology over the past several years.

Methods: Data were extracted retrospectively from consecutive necropsies performed at the UHWI over a two year period. The data were analysed to determine the categories and rates of discrepancy, and to determine the relation between discrepancy rates and age, sex, type and number of diagnoses for each patient, hospital service, and length of hospitalisation.

Results: Necropsies were performed on 446 patients; 348 were suitable for further analysis. The overall discrepancy rate was 48.4% and the diagnoses with the highest individual discrepancy rates were pneumonia (73.5%), pulmonary thromboembolism (68.3%), and myocardial infarction (66.7%). Males and older patients were more likely to have discrepant diagnoses. There was a high frequency of discrepancies in patients who died within 24 hours of admission, but there was no consistent relation between length of hospitalisation and discrepancy rate.

Conclusions: The high discrepancy rates documented at the UHWI are similar to those reported globally. This study supports previous attestations that the necropsy remains a vital tool for determining diagnostic accuracy, despite modern modalities of clinical investigation and diagnosis.

Keywords: necropsy, necropsy rate, diagnostic discrepancies, discrepancies, Jamaica

The necropsy is of tremendous value in the audit of diagnostic accuracy and in medical education. However, necropsy rates have shown a progressive decline, globally, over the past few decades,1–3 and this has been no different at our institution—the University Hospital of the West Indies (UHWI) in Kingston, Jamaica.4 We previously investigated the reasons for low necropsy rates at our institution,5 and found that the most common reasons for which clinicians failed to request necropsies were “confident clinical diagnoses” and “diagnoses confirmed by radiological or other laboratory investigations”. However, there have been many studies published that have shown high rates of discrepancy between clinical and necropsy diagnoses,6–12 and some have shown that diagnostic accuracy has not improved over the past 30 years, despite advances in medical investigative technology.8,11,13

“Necropsy rates have shown a progressive decline, globally, over the past few decades”

The aim of our study was to determine the discrepancy rates at our institution. There are only a handful of published studies such as this from the developing world,8–10,12 and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first from the English speaking Caribbean.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study examined data from consecutive necropsies performed in the department of pathology, University of the West Indies (UWI), over the two year period January 1999 to December 2000. The department performs necropsies for deaths occurring at the UHWI—the 500 bed, multidisciplinary teaching hospital attached to the Faculty of Medical Sciences at the UWI in Jamaica. We recorded the age, sex, duration of admission, and clinical and necropsy diagnoses for each patient. Clinical diagnoses were defined as those listed by the clinician on the necropsy request form/patient death card and all diagnoses that were established or assumed, as indicated in the patient records. Diagnoses were classified according to organ system, and those that involved two or more organ systems (for example, sepsis) were termed multisystemic. Deaths caused by trauma, other unnatural causes, or iatrogenic complications were excluded from further analysis. All necropsies were complete and were performed according to standard methodology, including relevant histological assessment. Necropsy diagnoses were those listed on the final report.

The clinical diagnoses were further classified as being either concordant or discrepant with respect to the necropsy diagnoses using a classification system based on that proposed by Underwood14 as follows:

- Category I:

- major discrepancy

- missed principal diagnosis definitely affecting clinical outcome.

- Category II:

- major discrepancy

- missed principal diagnosis possibly affecting clinical outcome.

- Category III:

- minor discrepancy

- missed secondary diagnosis, either symptomatic but not treated, or likely to have affected prognosis.

- Category IV:

- minor discrepancy

- missed secondary diagnosis that could not have been made clinically.

- Category V:

- concordant diagnosis.

We added a sixth category—overdiagnosis—to determine what proportion of discrepant cases represented clinical diagnoses uncorroborated at necropsy. These cases have been noted in some previously reported studies,11,15,16 and we believe that identifying overdiagnoses and determining the diseases for which they were mistaken would be useful for future clinical practice. This category of diagnoses was recorded as follows:

- Category VI:

- overdiagnosis, whether principal or secondary.

All the study pathologists arrived at a consensus regarding the categorisation of the diagnoses. In cases in which categorisation proved ambiguous, the benefit of doubt was awarded to the clinician. For example, where the necropsy proved any one of multiple (differential) clinical diagnoses proffered for a single case, the confirmed diagnosis was considered concordant, even though the clinician had not been definitive.

The data were used to calculate:

The discrepancy rate—the number of discrepancies expressed as a percentage of the total number of diagnoses.

The concordance rate—the number of concordant diagnoses expressed as a percentage of the total number of diagnoses.

These rates were then further analysed according to organ system, specific diagnosis, hospital service, and duration of admission.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data are expressed as frequencies, mean with standard deviation, and median with interquartile range, as appropriate. The level of agreement between clinical diagnoses and pathological diagnoses was assessed using the κ statistic. Analysis of variance was used to compare means of continuous variables. Differences in proportions were tested with the χ2 statistic. Logistic regression was used to examine the relation between concordance, age, and length of hospitalisation.

RESULTS

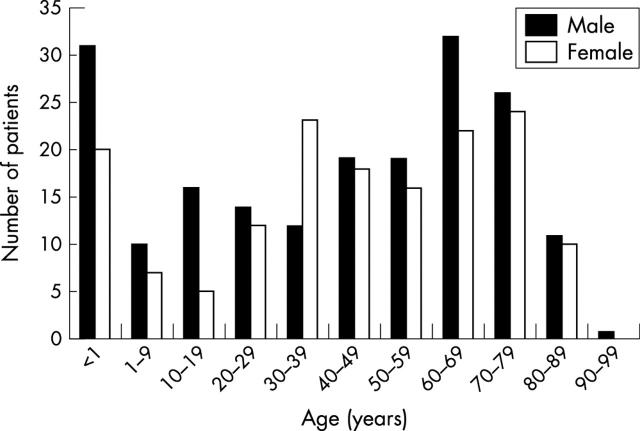

Necropsies were performed on 446 patients over the two year study period. Ninety eight were excluded from the study for the following reasons: 58 had unnatural diagnoses only, 18 were dead on arrival, 15 represented stillbirths/intrauterine deaths, three deaths occurred in other institutions, two bodies were decomposed, and two records were incomplete. The remaining 348 (78.0%) cases were analysed for this article, and consisted of 191 male and 157 female patients (male : female ratio, 1.2 : 1). The age distribution revealed peaks at less than 1 year of age (n = 51), at 60–69 (n = 54), and at 70–79 (n = 50) (fig 1). The median age was 44.5 years with an interquartile range of 47.

Figure 1.

Age and sex distribution of the 348 patients.

The 348 patient records analysed revealed 605 clinical diagnoses (191 patients had two or more diagnoses): 312 were concordant and 293 were discrepant with the necropsy diagnoses. There was a significant association between concordance and the number of diagnoses for each patient, such that the proportion of patients with multiple diagnoses that were concordant was less than expected (p < 0.0001). Similarly, there were significant associations between sex and concordance, with males having a significantly lower concordance frequency than females (p < 0.03), and between age and concordance, with older patients having a lower frequency of concordant diagnoses (p < 0.0001).

Table 1 shows the total number of overall, concordant, and discrepant diagnoses, in addition to the overall concordance (51.6%) and discrepancy (48.4%) rates, and the breakdown of these rates by organ system. The cardiovascular and respiratory systems comprised 54.2% of the total number of overall diagnoses and 60.4% of the total number of discrepant diagnoses. The systems exhibiting the highest discrepancy rates were the gastrointestinal (60.0%), the respiratory (57.7%), and the central nervous (54.4%) systems. There was a significant association between the frequency of concordant diagnoses and organ system. This association remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and total number of diagnoses, such that there was a greater than expected frequency of discrepant diagnoses in the respiratory system, and lower than expected frequency of discrepant diagnoses in the multisystemic category (p < 0.0001). Category I and category VI diagnoses accounted for most of the discrepancies.

Table 1.

Category of discrepancy and concordance and discrepancy rates by system

| System | Total ODN (%) | Category of discrepancy | Total DD | DR (%) | Total CD | CR (%) | ||||

| I | II | III | IV | VI | ||||||

| Respiratory | 168 (27.8) | 29 | 7 | 12 | 1 | 48 | 97 | 57.7 | 71 | 42.3 |

| Cardiovascular | 160 (26.4) | 27 | 16 | 15 | 0 | 22 | 80 | 50.0 | 80 | 50.0 |

| Central nervous | 68 (11.2) | 12 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 37 | 54.4 | 31 | 45.6 |

| Multisystemic | 69 (11.4) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 18 | 26.1 | 51 | 73.9 |

| Genitourinary | 42 (6.9) | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 19 | 45.2 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Gastrointestinal | 35 (5.8) | 14 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 21 | 60.0 | 14 | 40.0 |

| Reticuloendothelial | 21 (3.5) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 33.3 | 14 | 66.7 |

| Haematological | 13 (2.1) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 38.5 | 8 | 61.5 |

| Liver | 7 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 42.9 | 4 | 57.1 |

| Endocrine | 7 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 28.6 | 5 | 71.4 |

| Gall bladder and biliary tract | 6 (0.9) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 50.0 | 3 | 50.0 |

| Musculoskeletal | 4 (0.7) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25.0 | 3 | 75.0 |

| Skin | 3 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Breast | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| Total N | 605 | 97 | 47 | 35 | 8 | 106 | 293 | 48.4 | 312 | 51.6 |

| % | 100 | 33.1 | 16.0 | 11.9 | 2.7 | 36.2 | 100 | |||

CD, concordant diagnoses; CR, concordance rate; DD, discrepant diagnoses; DR, discrepancy rate; OD, overall diagnoses.

Table 2 gives a breakdown of the 10 most common discrepant diagnoses, which together represented 59.4% of the discrepancies. The highest discrepancy rates were seen with pneumonia (73.5%), pulmonary thromboembolism (68.3%), and myocardial infarction (66.7%). When analysed as a group, the top 10 discrepant diagnoses reflect the trend of the total number of discrepancies, with most contributions being made by diagnoses from categories I and VI (30.4% and 50%, respectively). Pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary thromboembolism made significant contributions to category VI diagnoses (58.3%, 68.2%, and 55.8% of their total discrepancies, respectively). Twelve of the 21 patients with an overdiagnosis of pneumonia had necropsy or clinical and necropsy findings of pulmonary congestion and oedema, or congestive cardiac failure. The same was true of eight of 24 patients with an overdiagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolism and six of 15 patients with an overdiagnosis of myocardial infarction. There was no consistent necropsy finding in patients with overdiagnosis of cerebrovascular accident or infective endocarditis. Congestive cardiac failure was never overdiagnosed, but was clinically missed 50.0% of the time. Of the 10 most common discrepant diagnoses, eight were more commonly diagnosed in male than in female patients, with male : female ratios for these eight diagnoses ranging from 1.2 : 1 to 2 : 1 (table 3). However, this difference in sex distribution was not significant.

Table 2.

Categories of discrepancy and discrepancy rates of the most common discrepant diagnoses

| Diagnosis | Category of discrepancy | Total DD | DR (%) | ||||

| I | II | III | IV | VI | |||

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 24* | 43 | 68.3 |

| Pneumonia | 4 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 21† | 36 | 73.5 |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 11 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 50.0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15‡ | 22 | 66.7 |

| Sepsis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12§ | 15 | 44.1 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 13 | 65.0 |

| Meningitis | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 63.6 |

| Primary brain tumours | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 55.6 |

| Infective endocarditis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 50.0 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 33.3 |

| Total N (%) 174 (100) | 53 (30.4) | 17 (9.8) | 16 (9.2) | 1 (0.6) | 87 (50.0) | ||

*Eight of 24 patients had a necropsy (or clinical and necropsy) diagnosis of congestive cardiac failure; †12 of 21 patients had a necropsy (or clinical and necropsy) diagnosis of pulmonary congestion and oedema, or congestive cardiac failure; ‡6 of 15 patients had a necropsy (or clinical and necropsy) diagnosis of congestive cardiac failure; §4 of 7 adult patients had necropsy (or clinical and necropsy) changes of congestive cardiac failure.

DD, discrepant diagnoses; DR, discrepancy rate.

Table 3.

Frequency of diagnosis of the most common discrepant diagnoses, by sex

| Diagnosis | Number of overall diagnoses | ||

| Male | Female | Total | |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 30 | 33 | 63 |

| Pneumonia | 31 | 18 | 49 |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 27 | 23 | 50 |

| Myocardial infarction | 19 | 14 | 33 |

| Sepsis | 19 | 15 | 34 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| Meningitis | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Primary brain tumours | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Infective endocarditis | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Total | 161 | 128 | 289 |

Table 4 shows an analysis of the data by service. Medicine includes: internal medicine (187), psychiatry (2), and dermatology (1); surgery cases include: surgical services (96) and obstetrics/gynaecology (11); and child health includes: child health proper (98) and Tropical Medicine Research Institute (8). There was a significant association between frequency of concordant diagnoses and service, with a lower than expected frequency of concordant diagnoses from the accident and emergency unit (A&E) (p < 0.0001). The discrepancy rates ranged from a high of 66.4% in A&E, to 31.6% in child health, and most of the discrepant diagnoses in A&E belonged to either category I or category VI.

Table 4.

Categories of discrepancies and discrepancy and concordance rates by service

| Service* | Total ODN (%) | Category of discrepancy | Total DD | DR (%) | Total CD | CR (%) | ||||

| I | II | III | IV | VI | ||||||

| Medicine | 190 (31.4) | 33 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 36 | 92 | 48.4 | 98 | 51.6 |

| A&E | 122 (20.2) | 31 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 31 | 81 | 66.4 | 41 | 33.6 |

| Child health | 106 (17.5) | 3 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 16 | 33 | 31.1 | 73 | 68.9 |

| Surgery | 107 (17.7) | 26 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 13 | 52 | 48.6 | 55 | 51.4 |

| ICU | 80 (13.2) | 4 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 35 | 43.8 | 45 | 52.5 |

| Total | 605 (100) | 97 | 47 | 35 | 8 | 106 | 293 | 48.4 | 312 | 51.6 |

*Medicine includes internal medicine, psychiatry, and dermatology; surgery includes all surgical specialties and obstetrics/gynaecology; Tropical Medicine Research Institute analysed with child health.

A&E, accident and emergency; CD, concordant diagnoses; CR, concordance rate; DD, discrepant diagnoses; DR, discrepancy rate; ICU, intensive care unit; OD, overall diagnoses.

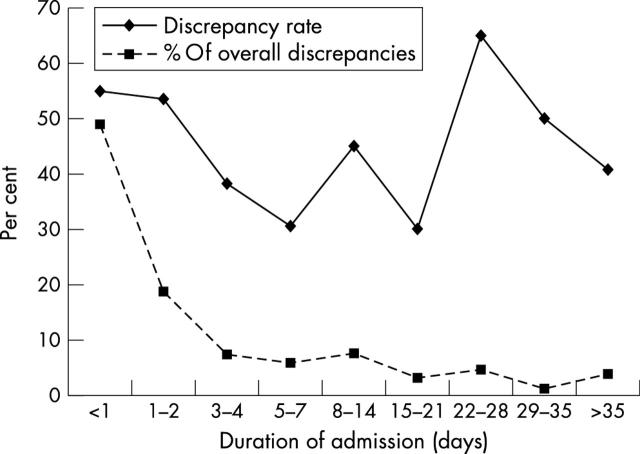

Figure 2 illustrates the influence of duration of admission on the percentage of discrepancies observed, and on the discrepancy rate. Patients hospitalised for less than 24 hours accounted for 48.8% of overall discrepant diagnoses, and there was a progressive decline in the number of discrepant diagnoses with increasing duration of admission. The figure also shows that the discrepancy rate did not vary significantly from one time period to the next.

Figure 2.

Discrepancy proportions by duration of admission.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies on concordance between clinical and postmortem diagnoses have used a variety of classification systems and formulas to categorise the nature of the association between the clinical and postmortem diagnoses, and for the quantitative expression of diagnostic accuracy. As a consequence, direct comparisons with our data were not always possible. As previously mentioned, for diagnoses in which classification was ambiguous, the benefit of the doubt was given to the clinician. In any case, a previous study has shown that the discrepancy rate is not influenced significantly by the assessor (whether clinician or pathologist) of the type and level of the discrepancies.7

The overall rate of discrepancy between clinical and postmortem diagnoses in our institution was 48.4%. There are no published data from the English speaking Caribbean with which to compare our figures, and although the methodology varied among studies, our discrepancy rate is comparable to the range of 28% to 60% calculated elsewhere.6–10,12 In some reports, the discrepancy rate was calculated for different decades,8,11,13 and it was shown that this rate has remained essentially unchanged, despite improvements in medical diagnostic technology over the past 30 years.

In some of the studies reviewed, only a single category of discrepancy or concordance was assigned to each patient, and in others it was not clear whether multiple or single categories were assigned. Both our study and that by Battle et al recorded multiple diagnoses, and therefore multiple categories, for each patient7; however, whereas Battle et al did not report an influence of number of diagnoses on the discrepancy rate,7 we showed that patients with multiple clinical diagnoses were less likely to show concordance than those with a single clinical diagnosis (p < 0.0001). This is understandable, because it is likely that multiple clinical diagnoses are often made in situations of uncertainty.

It has been reported previously that older patients have a lower frequency of concordant diagnoses,7,8,13,17 as was also found in our study, and this finding may result from atypical clinical presentations and the masking of clinical symptoms and signs in this age group. It is noteworthy that a previous study from our institution5 found that necropsy request rates were significantly lower for older patients than for younger ones—14.4% in those over 64 years compared with 50–55% in patients younger than 45 years. Cameron et al reported that they obtained significant improvements in concordance between clinical and necropsy diagnoses by improving their necropsy rates.18 Therefore, our findings underscore the need to increase the necropsy request rate in older patients.

Both our study and that by Battle and colleagues7 showed significant associations between sex and concordance, whereas others11,13 showed none. However, whereas we found a lower concordance frequency for male patients, Battle et al noted that female patients had a significantly greater risk of dying with a major discrepancy.7 In our study, those diseases that were most frequently discrepant were diagnosed more often in male than in female patients, but this finding was not significant.

Our data indicate a high rate of discrepancy for respiratory system diagnoses and for myocardial infarction (66.7%). The highest discrepancy rates were seen with pneumonia (73.5%) and pulmonary thromboembolism (68.3%). Pulmonary thromboembolism was also among the most common discrepant diagnoses in other studies,7,11,13,16,19 with discrepancy rates ranging from 46.8% to 75%. These three diagnoses made major contributions to category VI, and it was found that large proportions of patients with these overdiagnoses (57% for pneumonia, 40% for myocardial infarction, and 33% for pulmonary thromboembolism) had necropsy or clinical and necropsy findings of pulmonary oedema and congestion, or of congestive cardiac failure. These figures suggest that the clinical signs produced by left sided or congestive cardiac failure are often misinterpreted as representing one of these three diseases, and therefore, the differential of cardiac failure must be entertained when any of these diagnoses is being considered. The signs of congestive cardiac failure are also often missed—the entity carries a 50.0% discrepancy rate, which is represented solely by missed diagnoses. This suggests that the clinical signs of this condition may often be subtle, and must be carefully sought in the face of a suggestive clinical history. In patients with clinically undiagnosed pulmonary thromboembolism, there was no other significant necropsy diagnosis that was consistently present. This contrasts with the study by Mandelli et al,20 which showed that the clinical diagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolism was hampered by the presence of pneumonia.

The previously reported finding that infections contribute greatly to discrepancy rates6,7,9,11,16 was corroborated by our data, as demonstrated by the contributions of pneumonia, meningitis, infective endocarditis, and sepsis to the list of the 10 most common discrepancies (table 2). One group of authors21 alluded to the inherent difficulty in confirming a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia, but we are unsure of the reasons for the high rate of discrepancy for pneumonia in our study. However, we recognise that 58% of the patients concerned died within 48 hours of presentation to hospital, perhaps precluding thorough investigation for infectious disease.

As far as overdiagnoses of infections are concerned, we have already made reference to the finding of pulmonary congestion and oedema or congestive cardiac failure in patients with an overdiagnosis of pneumonia. Sepsis was the other major infection related contributor to this category. A large number (41.7%) of patients with an overdiagnosis of sepsis were neonates with signs of respiratory distress. The presumption of sepsis until proved otherwise is standard procedure for neonates with respiratory distress who are admitted to the neonatal unit at our institution. In adult patients with an overdiagnosis of sepsis, the only consistent finding (seen in 57% of cases) at necropsy was that of congestive cardiac failure, but in 50% of these patients the diagnosis of congestive cardiac failure had also been made clinically.

Take home messages.

The overall discrepancy rate between clinical and necropsy diagnoses at the University Hospital of the West Indies was 48.4% and the diagnoses with the highest individual discrepancy rates were pneumonia (73.5%), pulmonary thromboembolism (68.3%), and myocardial infarction (66.7%)

These high discrepancy rates are similar to those reported globally

This study supports previous attestations that the necropsy remains a vital tool for determining diagnostic accuracy, despite modern modalities of clinical investigation and diagnosis

Like Battle and colleagues7 and Olle-Goig et al,10 we documented a high frequency of discrepancies in patients hospitalised for less than 24 hours, and similar to the findings of Battle et al,7 there was no consistent relation between overall duration of hospitalisation and discrepancy rate. The lower than expected frequency of concordant diagnoses from the A&E department (p < 0.0001) correlates with the high frequency of discrepancies seen in the “less than 24 hour” period of hospitalisation. Although it is possible that short periods of hospitalisation (< 24 hours) may preclude detailed examination and investigation, Battle and colleagues7 have suggested that expected decreases in discrepancy rates with time may be hindered by the failure of clinicians to recognise new signs and symptoms in patients already being treated for other diseases.

It has been suggested previously that the global decrease in necropsy rates may cause artefactual increases in discrepancy rates, because perhaps only more difficult cases are now being necropsied.22,23 Whether this is true or not, the results of our study support previous attestations that the necropsy remains a vital tool for determining diagnostic accuracy, despite modern modalities of clinical investigation and diagnosis, and also show that developing nations exhibit trends in diagnostic accuracy that are similar to those in more developed countries. Discrepancy rates will only decrease when more necropsies are requested, allowing clinicians to appreciate the “different faces” of various diseases, and allowing continual audit of diagnostic accuracy.

Abbreviations

A&E, accident and emergency

UWI, University of the West Indies

UHWI, University Hospital of the West Indies

REFERENCES

- 1.Cameron HM, McGoogan E, Clarke J, et al. Trends in hospital necropsy rates: Scotland 1961–74. BMJ 1977;1:1577–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanner MA. In perspective of the declining necropsy rate. Attitudes of the public. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994;118:878–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood MJ, Guha AK. Declining clinical necropsy rates versus increasing medicolegal necropsy rates in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001;125:924–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escoffery CT, Shirley SE. Necropsy rates at the University Hospital of the West Indies, 1968–1997. West Indian Med J 2000;49:164–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson TN, Escoffery CT, Shirley SE. Necropsy request practices in Jamaica: a study from the University Hospital of the West Indies. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:608–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevanovic G, Tucakovic G, Dotlic R, et al. Correlation of clinical diagnoses with necropsy findings: a retrospective study of 2,145 consecutive necropsies. Hum Pathol 1986;17:1225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Battle RM, Pathak D, Humble CG, et al. Factors influencing discrepancies between premortem and postmortem diagnoses. JAMA 1987;258:339–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho FM, Widmer MR, Cruz M, et al. Clinical diagnosis versus necropsy. Bull Pan Am Health Organ 1991;25:41–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarode VR, Datta BN, Banerjee AK, et al. Necropsy findings and clinical diagnoses: a review of 1,000 cases. Hum Pathol 1993;24:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olle-Goig JE, Canela-Soler J. The value of the necropsy in a rural hospital of Haiti. Trop Doct 1993;23:54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirch W, Schafii C. Misdiagnosis at a university hospital in 4 medical eras. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ermenc B. Discrepancies between clinical and post-mortem diagnoses of causes of death. Med Sci Law 1999;39:287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman L, Sayson R, Robbins S, et al. The value of the necropsy in three medical eras. N Engl J Med 1983;308:1000–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Underwood JCE. Necropsies and clinical audit. In: Burton JL, Rutty GN, eds. The hospital necropsy. London: Arnold, 2001:170–7.

- 15.Cameron HM, McGoogan E. A prospective study of 1152 hospital necropsies: II. Analysis of inaccuracies in clinical diagnoses and their significance. J Pathol 1981;133:285–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercer J, Talbot IC. Clinical diagnosis: a post-mortem assessment of accuracy in the 1980s. Postgrad Med J 1985;61:716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron HM, McGoogan E. A prospective study of 1152 hospital necropsies: I. Inaccuracies in death certification. J Pathol 1981;133:273–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameron HM, McGoogan E, Watson H. Necropsy: a yardstick for clinical diagnoses. BMJ 1980;281:985–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurlbeck WM. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis in a Canadian teaching hospital. Can Med Assoc J 1981;125:443–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandelli V, Schmid C, Zogno C, et al. False negatives and false positives in acute pulmonary embolism: a clinical–postmortem comparison. Cardiologia 1997;42:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonds LA, Gaido L, Woods JE, et al. Infectious diseases detected at necropsy at an urban public hospital, 1996–2001. Am J Clin Pathol 2003;119:866–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonderegger-Iseli K, Burger S, Muntwyler J, et al. Diagnostic errors in three medical eras: a necropsy study. Lancet 2000;355:2027–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shojania KG, Burton EC, McDonald KM, et al. Changes in rates of necropsy-detected diagnostic errors over time. A systematic review. JAMA 2003;289:2849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]