Abstract

Background: Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) is expressed in a proportion of carcinomas derived from follicular thyroid cells and respiratory epithelium. Immunohistochemical detection of this protein was shown previously to be a helpful aid in tumour diagnosis, specifically in deciding whether a tumour is primary to the lung/thyroid gland or metastatic. Recently, TTF-1 expression was also observed in certain areas of postnatal brain.

Aim/Method: To investigate the expression of TTF-1 protein in a spectrum of 73 primary brain tumours including astrocytomas, glioblastomas, ependymomas, oligodendrogliomas, medulloblastomas, and gangliogliomas of different sites.

Results: All the tumours were negative for TTF-1 except for two ependymomas of the third ventricle.

Conclusions: The expression of TTF-1 in brain tumours appears to be site specific rather than associated with tumour dedifferentiation. The presented expression of TTF-1 protein in certain primary brain tumours should be taken into consideration when interpreting the immunohistochemical staining of brain tumours of uncertain primary site.

Keywords: thyroid transcription factor 1, brain tumours, ependymoma

Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) is a member of the homeodomain transcription factor family, which plays an important role in early fetal differentiation and morphogenesis.1 TTF-1 mRNA and protein remain detectable in the postnatal period in human follicular thyroid cells and respiratory epithelium, particularly in alveolar type II cells and in bronchiolar Clara cells.1 The expression of TTF-1 protein is retained in most carcinomas derived from these cell types and, except for high grade neuroendocrine carcinomas,2 immunohistochemical detection of TTF-1 can be a helpful aid in discerning the primary site of a tumour.3,4

“There is increasing evidence that thyroid transcription factor 1 is expressed transiently in discrete areas of the brain postnatally”

The detection of TTF-1 protein can also be useful in deciding whether a tumour is primary or metastatic to the brain.5 However, TTF-1 is known to be expressed during development in restricted areas of the basal forebrain.1 Moreover, there is increasing evidence that this transcription factor is expressed transiently in discrete areas of the brain postnatally.6–8 This raises question of whether TTF-1 is expressed in primary brain tumours (PBTs) and whether the diagnostic identification of TTF-1 would be useful to estimate the biological properties of PBTs. Therefore, we performed a preliminary immunohistochemical study to investigate the expression of TTF-1 protein in a spectrum of primary brain tumours of different types and localisations.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this pilot study, we investigated 73 PBTs from different sites in both children and adults (table 1). The patients’ medical records were reviewed so that relevant analyses of survival and of a possible prognostic impact of TTF-1 detection could be performed.

Table 1.

Series of primary brain tumours investigated in our study

| Number of cases | Mean age (median); sex | Localisation | |

| Astrocytic tumours | 33 | ||

| Pilocytic astrocytomas | 8 | 7.7 (6); 4F:4M | 2× ChO; 2× HT; 4× CB |

| Astrocytomas, grade II | 6 | 18.3 (18); 2F:4M | 2× TP; 1× O; 1× Th; 1× FL; 1× HT |

| Anaplastic astrocytomas | 6 | 30.1 (29); 4F:2M | 2× P; 1× FT; 1× T; 1× TP; 1× HT |

| Glioblastomas | 13 | 58.1 (61); 5F:7M | 6× P; 1× O; 2× PO; 2× T; 2× TP |

| Ependymomas | 27 | ||

| Ependymomas, grade II | 11 | 5.3 (7); 4F:7M | 6× PF 3× vIII, 2× vL |

| Anaplastic ependymomas | 16 | 4.8 (5); 8F :8M | 8× PF, 2× vIII, 6× vL |

| Oligodendrogliomas | 3 | 43.7 (45); 1F:2M | 2× P; 1× FL |

| Medulloblastomas | 7 | 7.7 (7); 3F:4M | 7× CB |

| Gangliogliomas | 3 | 16.6 (12); 1F:2M | 2× T; 1× Th |

Age is given in years.

CB, cerebellum; ChO, optical chiasma; F, female; FL, frontal lobe; FT, frontotemporal region; HT, hypothalamus; M, male; O, occipital lobe; P, parietal lobe; PF, posterior fossa; PO, parieto-occipital region; T, temporal lobe; Th, thalamus; TP, temporoparietal region; vIII, third ventricle; vL, lateral ventricle.

Resected tumours were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. Tissue sections were dewaxed and rehydrated. Heat induced epitope retrieval was performed in sodium citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0), which was warmed to 96°C in a water bath for 40 minutes. Mouse monoclonal antibody against TTF-1 (clone 8G7G3/1; Neomarkers, Freemont, California, USA) was used at a dilution of 1/100; the incubation was performed overnight at 4°C. The antigen–antibody complexes were visualised by a biotin–streptavidin detection system (ChemMate detection kit; DakoCytomation, Ely, Cambridgeshire, UK) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Fluka Chemie GmbH, Buchs, Switzerland) as chromogen. All sections were counterstained with Harris’ haematoxylin. Nuclear staining only was considered as a positive result. Tissues of non-neoplastic thyroid gland and lung and of a pulmonary adenocarcinoma with known TTF-1 positivity served as positive controls.

To confirm the nature of the tumours, each was subjected to immunoperoxidase staining using primary monoclonal antibodies (DakoCytomation) against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; clone 6F2; diluted 1/1000), synaptophysin (clone SY38; diluted 1/20), and cytokeratin (clone AE1/AE3; diluted 1/200).

RESULTS

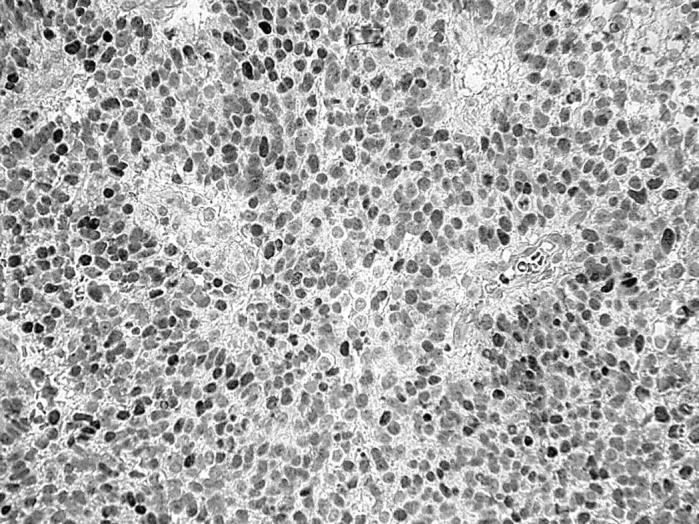

All PBTs were negative for TTF-1 except from two ependymomas in which strong nuclear staining was seen in most of the tumour cells. In these ependymal tumours, the cell processes of the perivascular pseudorosettes were stained by anti-GFAP antibody, but immunohistochemistry for cytokeratin and synaptophysin was negative. Both of these ependymomas were localised in the third cerebral ventricle, were incompletely resected, and the children were treated by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. One of these ependymomas (in a 5 year old boy) was classified as grade III (fig 1). It recurred 14 months after surgery and the patient died as a result of tumour progression four months later. The other patient had grade II ependymoma (a 12 year old girl); the patient is well 72 months after tumour removal.

Figure 1.

Intense nuclear immunoreactivity for TTF-1 in an anaplastic ependymoma of the third ventricle (counterstained lightly with haematoxylin).

DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis that TTF-1 might be upregulated in the most dedifferentiated PBTs and might thus serve as a marker of tumour aggressiveness was not confirmed by the results. All glioblastomas, medulloblastomas, and all except one anaplastic ependymoma were negative. The only TTF-1 positive tumours were two ependymomas of different grades arising from the walls of the third ventricle. Such a finding is of interest, because TTF-1 has been shown to be essential for embryonic morphogenesis, particularly of the diencephalon; in mice carrying a null mutation of the TTF-1/Nkx-2.1 gene, the walls of the third ventricle were fused together and certain nuclei of the hypothalamus were underdeveloped.9 Furthermore, recent reports have shown that TTF-1 is localised in rats to specific hypothalamic neurones and astrocytes of the median eminence, in addition to ependymal/subependymal cells of the third ventricle, which are thought to be involved in the control of sexual maturation6 and body fluid homeostasis8 in the postnatal period. We speculate that the TTF-1 positive tumours may have originated from these specific cell subsets. Because one of the ependymomas had anaplastic morphology, whereas the other was grade II, with a favourable outcome, the presence of TTF-1 expression is probably site specific, rather than being associated with tumour dedifferentiation. There is a parallel in a series of lung carcinomas, in which TTF-1 expression was not associated with the grade of the tumours.3,4 This concept needs to be verified in a larger series of cases.

“Our hypothesis that thyroid transcription factor 1 might be upregulated in the most dedifferentiated primary brain tumours and might thus serve as a marker of tumour aggressiveness was not confirmed by the results”

Take home messages.

Most primary brain tumours are thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) negative

However, TTF-1 protein might be expressed in certain brain tumours, especially those in the third ventricle region

These facts should be taken into consideration when interpreting the immunohistochemical staining of brain tumours of uncertain origin

Most PBTs can be distinguished from metastatic tumours by histology. However, epithelioid features of PBTs, including papillary pattern of growth of brain tumours (particularly of ependymomas), can cause diagnostic problems.10 In such cases, the interpretation of TTF-1 protein expression in brain tumour cells could be misleading, especially in small biopsy specimens.

In conclusion, most PBTs are TTF-1 negative; however, TTF-1 protein might be expressed in certain brain tumours, especially those in the third ventricle region. This should be taken into consideration when interpreting the immunohistochemical staining of brain tumours of uncertain origin.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Investigation Projects granted by Ministry of Health (VZ FNM 00000064203) and Ministry of Education (VZ J13/98:111300004) of Czech Republic.

Abbreviations

GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein

PBT, primary brain tumour

TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor 1

REFERENCES

- 1.Bingle CD. Thyroid transcription factor-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1997;29:1471–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ordonez NG. Value of thyroid transcription factor-1 immunostaining in distinguishing small cell lung carcinomas from other small cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufmann O , Dietel M. Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 in pulmonary and extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas and other neuroendocrine carcinomas of various primary sites. Histopathology 2000;36:415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zamecnik J , Kodet R. Value of thyroid transcription factor-1 and surfactant apoprotein A in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary carcinomas: a study of 109 cases. Virchows Arch 2002;440:353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srodon M , Westra WH. Immunohistochemical staining for thyroid transcription factor-1: a helpful aid in discerning primary site of tumor origin in patients with brain metastases. Hum Pathol 2002;33:642–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee BJ, Cho GJ, Norgren RB Jr, et al. TTF-1, a homeodomain gene required for diencephalic morphogenesis, is postnatally expressed in the neuroendocrine brain in a developmentally regulated and cell-specific fashion. Mol Cell Neurosci 2001;17:107–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura K , Kimura S, Yamazaki M, et al. Immunohistochemical analyses of thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein in the fetal and adult rat hypothalami and pituitary glands. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 2001;130:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Son YJ, Hur MK, Ryu BJ, et al. TTF-1, a homeodomain-containing transcription factor, participates in the control of body fluid homeostasis by regulating angiotensinogen gene transcription in the rat subfornical organ. J Biol Chem 2003;278:27043–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura S , Hara Y, Pineau T, et al. The T/ebp null mouse: thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein is essential for the organogenesis of the thyroid, lung, ventral forebrain, and pituitary. Genes Dev 1996;10:60–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinman GM, Zagzag D, Miller DC. Epithelioid ependymoma: a new variant of ependymoma: report of three cases. Neurosurgery 2003;53:743–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]