Abstract

B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the follicular subtype (grade 3/3) affecting the nasopharynx and breast, and containing foci of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, was diagnosed in a 56 year old white woman who was a longstanding heavy smoker. Four years before this she had developed stage 1a mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma affecting the right inguinal region, which was treated by irradiation and chemotherapy without recurrence. Review of the original Hodgkin lymphoma histology demonstrated a small focus of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. This is thought to be the first recorded case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis occurring in a sequential discordant lymphoma. Its importance is discussed.

Keywords: Langerhans cell, discordant lymphoma, breast, lymph node, nasopharynx

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a group of disorders characterised by the proliferation of Langerhans cells, a cell type that expresses CD1a and S100 and contains Birbeck granules,1,2 which can be demonstrated by ultrastructural examination. The underlying stimulus is unknown. A viral aetiology has not been substantiated. However, cigarette smoking is an aetiological factor, especially in pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis.3 Although some argue that Langerhans cell histiocytosis represents a reactive immune disorder,4,5 the relentless progression seen in a proportion of cases and the successful responses to cancer based treatment modalities suggest a neoplastic process.6 Langerhans cell histiocytosis has a complex relation with other forms of neoplasia. For example, it may be found admixed with lymphoma in the diagnostic biopsy, or may precede or follow the diagnosis of lymphoma.

CASE REPORT

A 52 year old white woman first presented with right inguinal lymphadenopathy. There was no other lymphadenopathy and no hepatosplenomegaly. She had no B symptoms. Her blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, lactate dehydrogenase, bone marrow examination, and computerised tomography scans of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis were all normal. She was a longterm heavy smoker.

A biopsied lymph node measured 60 × 40 × 10 mm. Microscopically, the nodal architecture was effaced, without fibrosis. The paracortex was expanded and infiltrated by a mixed cell population composed of eosinophils, lymphocytes, mononuclear Hodgkin cells, and occasional Reed-Sternberg cells. The Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells expressed CD15 and CD30. A diagnosis of mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma stage 1a was made. The patient was treated with two cycles of ABVD chemotherapy and involved field (right iliac, inguinal, and femoral) radiotherapy, given as 17 fractions over 24 days. Complete remission was achieved.

The patient re-presented four years later with a three month history of cold and nausea followed by impaired hearing. There was no tinnitus or imbalance. Neither peripheral lymphadenopathy nor hepatosplenomegaly were detected. Throat examination revealed a hard, smooth, rounded nasopharyngeal swelling, which was thought clinically to be nasopharyngeal carcinoma or recurrent lymphoma. Four months later, an ultrasound examination revealed a left intramammary lesion measuring 9 mm in diameter. Bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsies were normal. Computed tomography imaging of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis showed no soft tissue or bony abnormalities. The nasopharyngeal and breast masses were biopsied.

PATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS

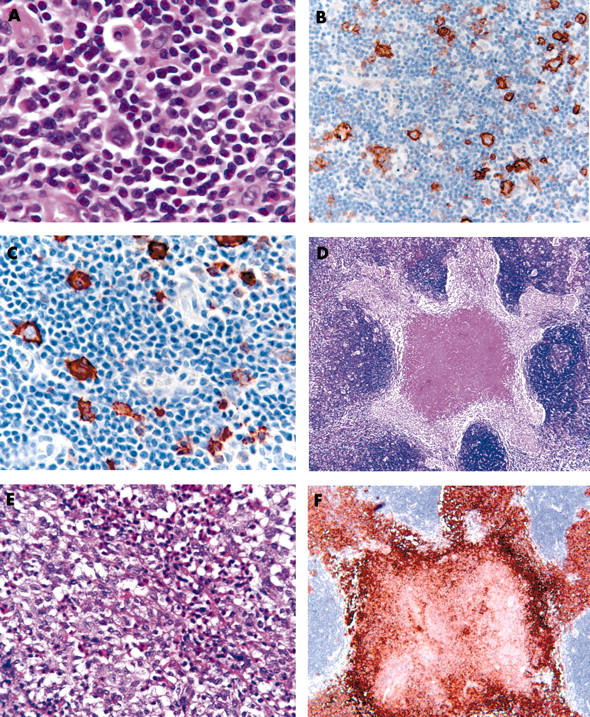

A review of the previous inguinal lymph node haematoxylin and eosin and immunocytochemical slides confirmed the diagnosis of mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma with tumour cells coexpressing CD15 and CD30 (fig 1A–C). In addition, a well defined nodule of Langerhans cells, with scattered eosinophils and central necrosis, measuring 4 mm across, was identified (fig 1D–E). The Langerhans cells showed pale clefted nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, and indistinct cell borders. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong S100 and CD1a (fig 1F) expression, thereby confirming Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Figure 1.

The Hodgkin lymphoma. (A) Reed-Sternberg and Hodgkin cells positive for (B) CD15 and (C) CD30 immunostaining. (D, E) Nodule of Langerhans cells with eosinophils showing central necrosis (haematoxylin and eosin stain). (F) Langerhans cells with strong CD1a expression.

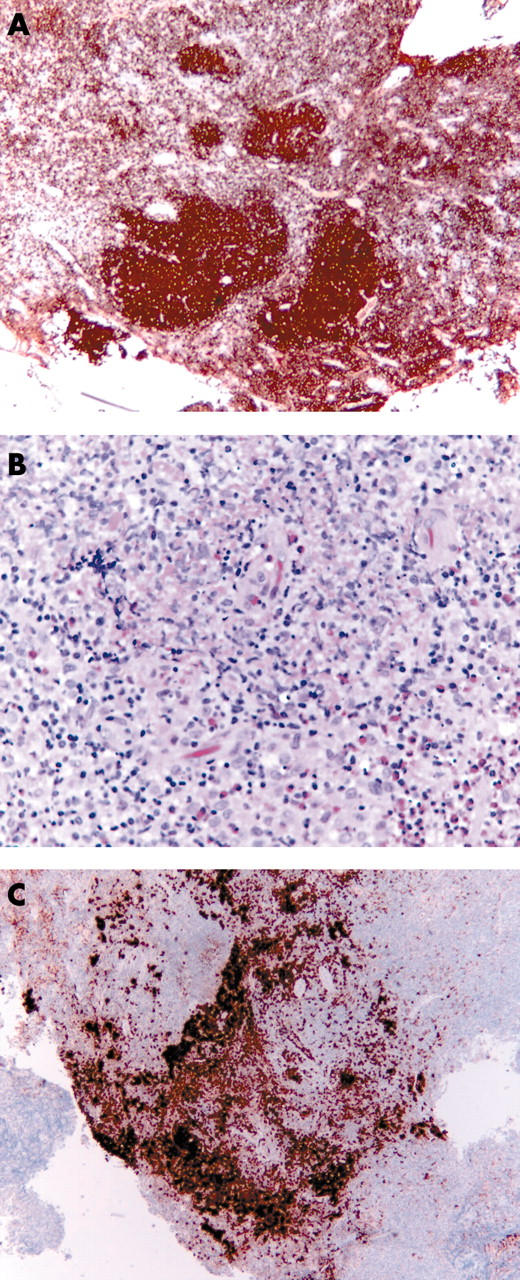

The nasopharyngeal biopsies consisted of three irregular tissue fragments, together measuring 17 × 15 × 10 mm. The breast biopsy was fatty tissue measuring 30 × 20 × 10 mm, containing a nodule 10 mm in diameter. Both the nasopharyngeal and breast biopsies showed the histological and immunocytochemical features of B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of follicular subtype (grade 3/3), with a follicular pattern (fig 2A) and associated nodules of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (fig 2B). No lymph node architecture was identified. The follicle centre cells of the nasopharyngeal lymphoma showed weak BCL2 expression and κ immunoglobulin light chain restriction. Both biopsies contained nodules (6 mm in the nasopharynx, 4 mm in the breast) of CD1a (fig 2C) and S100 positive Langerhans cells, indicating Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Figure 2.

The nasopharyngeal B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. (A) CD20 expression and (B) nodules of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (C) with strong CD1a positivity.

Epstein-Barr virus was not detected within the tumour cells of the nasopharyngeal and breast non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNA in situ hybridisation preparations. The control probes demonstrated RNA preservation in all the samples except for the Hodgkin lymphoma tissue. The Hodgkin lymphoma tissue was therefore not assessable.

DISCUSSION

Langerhans cell histiocytosis has a complex association with malignant lymphoma: it may precede, occur with, or follow it.7 Most commonly, and as was the circumstance in the initial clinical presentation of the patient reported here, the diagnoses are concurrent, with the lymphoma being of Hodgkin type. This association is rare, and has been estimated to be 0.3% for Hodgkin lymphoma.8

The small size of the initial Langerhans cell histiocytosis focus in the biopsied Hodgkin lymphoma node suggests that the Langerhans cell histiocytosis may represent an abnormal (although possibly neoplastic) stromal response to the Hodgkin lymphoma microenvironment. The identification, four years later, of Langerhans cell histiocytosis within non-Hodgkin lymphoma indicates that the Hodgkin directed radiotherapy and chemotherapy had not eradicated the Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and that the Langerhans cell histiocytosis cells had dispersed far beyond their presumed site of origin within the groin node. In situ hybridisation analysis showed no evidence of Epstein-Barr virus in the two lymphomas.

“This case suggests a degree of interdependence in the growth of Langerhans cell histiocytosis and the non-Hodgkin lymphoma”

The relative risk of secondary non-Hodgkin lymphoma after treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma ranges from 31.5 to 56.8 times for radiotherapy and radiotherapy with chemotherapy, respectively.9 There does not appear to be a significant increase with chemotherapy alone.9 Given this, no assumption should be made that the Langerhans cell histiocytosis necessarily predisposed to the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in our case. However, it should be noted that the distribution of the follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma (two extranodal sites, oropharynx and breast, without lymph node involvement) is distinctly unusual. In this circumstance, it is reasonable to think that the local environment (that is, the presence of Langerhans cell histiocytosis) may well have had a role in the distribution, and therefore the development, of the non-Hodgkin lymphoma. With regard to the development of the Langerhans cell histiocytosis, its presence in the non-Hodgkin lymphoma biopsies, despite the absence of other clinically detectable Langerhans cell histiocytosis, suggests that the non-Hodgkin lymphoma microenvironment was conducive to Langerhans cell histiocytosis growth. Therefore, this case suggests a degree of interdependence in the growth of Langerhans cell histiocytosis and the non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In conclusion, we present a case of sequential discordant malignant lymphoma. The presence of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in both types of lymphoma and the patterns of disease illuminate some of the complex relations between these disease processes.

Take home messages.

To our knowledge, we describe the first case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis occurring in sequential discordant lymphoma

The presence of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in both histologically distinct lymphoma types implies widespread dispersal of Langerhans cell histiocytosis cells from the presumed site of origin

The findings suggest a degree of interdependence in the growth of Langerhans cell histiocytosis and non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr D Hilton for the photographs and the EBV in situ hybridisation analysis and Miss R Baugh for her technical support

REFERENCES

- 1.Birbeck MS, Breathnach AJ, Everall JD. An electron microscopic study of basal melanocytes and high level clear cells (Langerhan’s cells) in vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol 1961;37:51–64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nezelof C , Basset F, Rousseau MF. Histiocytosis X: histiogentetic arguments for Langerhans cell origin. Biomedicine 1973;18:365–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colby TV, Lombard C. Histiocytosis X in the lung. Hum Pathol 1983;14:847–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Aglio GJ, Favora BE, Ladish S. Workshop on the childhood histiocytosis X: concepts and controversies. Med Pediatr Oncol 1986;14:104–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osband ME, Lipton JM, Lavin P, et al. Histiocytosis X: demonstration of abnormal immunity. N Engl J Med 1981;304:146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.William CL. Detection of clonal histiocytosis in LCH; biology and clinical significance. Br J Cancer 1994;70 (suppl 23) :529–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egeler RM, Neglia JP, Puccetti DM, et al. Association of Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis with malignant neoplasms. Cancer 1993;71:865–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns BF, Cobly TV, Dorfman RF. Langerhan’s cell granulomatosis (histiocytosis X) associated with malignant lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:529–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krikorian JG, Burke JS, Rosenberg SA, et al. Occurrence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after therapy for Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med 1979;300:452–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]