Abstract

Background/Aims: CD10 (CALLA) has recently been reported to be expressed in spindle cell neoplasia, and has been used to differentiate endometrial stromal sarcoma from leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma. In the breast, myoepithelial cells express CD10, but there are few studies of the expression of CD10 in mammary fibroepithelial lesions.

Methods: Stromal CD10 expression was studied in 181 mammary phyllodes tumours (102 benign, 51 borderline malignant, and 28 frankly malignant) and 33 fibroadenomas using immunohistochemistry, to evaluate whether differences in expression correlated with the degree of malignancy.

Results: There was a progressive increase in the patients’ age and tumour size, from fibroadenoma to phyllodes tumours with an increasing degree of malignancy (p < 0.001). Stromal CD10 expression was positive in one of 33 fibroadenomas, six of 102 benign phyllodes tumours, 16 of 51 borderline malignant phyllodes tumours, and 14 of 28 frankly malignant phyllodes tumours. The difference was significant (p < 0.001) and an increasing trend was established. Strong staining was seen in subepithelial areas with higher stromal cellularity and activity. Stromal CD10 expression had a high specificity (95%) for differentiating between benign lesions (fibroadenomas and benign phyllodes tumours) and malignant (borderline and frankly malignant) phyllodes tumours.

Conclusions: CD10 may be a useful adjunct in assessing malignancy in mammary fibroepithelial lesions.

CD10, or the common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia antigen (CALLA), is a cell surface neutral endopeptidase, and is expressed by lymphoid precursor cells and some B cells.1–4 It has long been used as a marker for leukaemia, Burkitt lymphoma,5 and follicular lymphoma.4 Recently, it has been shown that CD10 is expressed in normal tissues, including myoepithelial cells of the breast and salivary glands, apocrine metaplastic cells and in situ adenocarcinoma of the breast, apical glandular surfaces of the small and large intestine, pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells, prostatic duct cells, glomerular cells of the kidney, and stromal cells in the endometrium and bone marrow.6,7,8,9,10,11 In non-haemopoietic tissue, CD10 expression was found in various neoplasms—notably, carcinomas, gliomas, germ cell tumours of the mediastinum, and melanoma.6,12–14 Of interest, CD10 expression has also been reported in spindle cell neoplasms such as coetaneous dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma,15 and in endometrial stromal sarcoma.16–18 In fact, CD10 has been used as a diagnostic marker to differentiate endometrial stromal sarcoma from leiomyoma,17 although some authors have recently suggested that CD10 can also be expressed in malignant mixed mullerian tumours and high grade leiomyosarcomas.19

“Only a single study has assessed the use of CD10 expression in the stroma of invasive carcinoma of the breast as a possible predictor of clinical outcome”

However, CD10 expression is not well documented in the breast, with only a few reports on its expression in myoepithelial cells,6,20 and its use as an aid to the diagnosis of problematic lesions.21 Studies of CD10 expression in breast stromal cells are even rarer, with only a single study assessing the use of CD10 expression in the stroma of invasive carcinoma of the breast as a possible predictor of clinical outcome.22 Similarly, CD10 expression in mammary stromal neoplasms, most notably phyllodes tumours and fibroadenomas, had not been well documented in the literature, with only one published report in a small series of 13 fibroadenomas and three phyllodes tumours.23

Mammary phyllodes tumour is an uncommon stromal epithelial neoplasm that usually occurs in middle aged women.24–28 Based on a combination of histological criteria, phyllodes tumours can be divided into benign, borderline, and frankly malignant groups.24,29 Although all groups of phyllodes tumours show a propensity to recur locally, the borderline and frankly malignant groups may also metastasise to other visceral organs.

In our current study, the immunohistochemical expression of CD10 was evaluated in the stromal cells of a large series of mammary phyllodes tumours and fibroadenomas, with the aim of determining whether the degree of CD10 expression in the stromal cells is related to the grade of the tumour.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The histological files of four participating institutions were searched for phyllodes tumours of the breast. The number of years searched ranged from four to 15. The paraffin wax blocks were retrieved and 4 μm thick slides were prepared routinely and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. All the slides were reviewed and all the diagnoses were confirmed histologically as biphasic lesions with both epithelial and stromal components. The epithelial element was benign, and there could be epithelial hyperplasia. The stroma was cellular and expanded, resulting in a leaf-like pattern. The degree of malignancy was assessed by the following histological parameters: (1) stromal cellularity; (2) nuclear pleomorphism; (3) stromal overgrowth; (4) mitotic rate; and (5) margin of the tumour (whether infiltrative or rounded). Parameters 1 and 2 were graded as low/mild, moderate, or severe; stromal overgrowth was graded as present (absence of epithelial element within a low power field (×40)) or absent (presence of epithelial element within a low power field) (Nikon Labophot; field area, 1.9 mm2); and the mitotic count was expressed as the number of mitotic figures for each 10 high power fields (×400; Nikon Labophot; field area, 0.19 mm2). As described previously,30 a diagnosis of benign phyllodes tumour was made when there was low cellularity, no stromal overgrowth, mild pleomorphism, a rounded margin, and a mitotic count of ⩽ 2/10 high power fields. Malignant phyllodes tumour was diagnosed when the mitotic count was ⩾ = 5/10 high power fields together with stromal overgrowth and an infiltrative margin. Phyllodes tumour of borderline malignancy was diagnosed when the criteria for malignant phyllodes tumour were not totally fulfilled.

Fibroadenoma was also searched in one of the institutions (Prince of Wales Hospital, China) for a three month period in 2003, and all the consecutive cases were reviewed and the diagnoses confirmed if the lesions showed a biphasic pattern, with a bland epithelial component, and with the stromal component showing low cellularity, minimal to absent stromal mitoses, and the absence of a large frond-like growth pattern of the stroma. One representative section was taken for CD10 staining.

For the assessment of CD10 expression, a representative slide from each case was stained using an antibody against CD10 (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; 1/10 dilution; microwave antigen retrieval) with the avidin biotin method. Stromal cell staining was assessed, using cytoplasmic staining of the breast myoepithelium as internal control. The staining intensity was graded as 0 (no staining), or low, intermediate, or high if the staining was much weaker, slightly weaker, or of the same intensity as that of the myoepithelium, respectively. The percentage of cells stained was also assessed. The tumour was considered positive for CD10 if there was moderate to strong cytoplasmic staining in 20% or more of the stromal cells, particularly in the subepithelial location.

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was used to determine differences in CD10 expression between groups with different degrees of malignancy, and one way ANOVA was used to determine whether the trend was significant. Significance was established at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Our study included 181 cases of phyllodes tumour, obtained from 176 patients. There were 102 benign phyllodes tumours, 51 borderline malignant phyllodes tumours, and 28 malignant phyllodes tumours. The patients’ ages ranged from 14 to 77 years (mean, 42). The tumour sizes ranged from 0.8 to 22 cm, (mean, 4.8). One hundred and six patients were Chinese, 26 patients were other Asians, and 30 were white, whereas the ethnic group was not known in 14 patients. These 181 cases included 10 tumours from five patients, who had one recurrence each, three initial tumours that subsequently recurred, six first recurrences from six different patients, and three second recurrences from another three patients. Two of the malignant phyllodes tumours developed distant metastases. Thirty three fibroadenomas were obtained. The patients ages ranged from 20 to 58 years (mean, 35), and the lesional sizes ranged from 0.8 to 5 cm, (mean, 2.0). All patients with fibroadenomas were Chinese.

For the 102 benign phyllodes tumours, the patients ages ranged from 14 to 60 years (mean, 40), and the tumour sizes ranged from 0.8 to 22 cm (mean, 4); for the 51 borderline malignant phyllodes tumours, the age range was 15–77 years (mean, 45), and the tumour size range was 1–20 cm (mean, 5.4); for the 28 malignant phyllodes tumours, the age range was 19–70 years (mean, 46), and the tumour size range was 1.5–22 cm (mean, 6.5).

There was a progressive increase from fibroadenoma to phyllodes tumours of benign, borderline malignancy, and frank malignancy for both age and tumour size. The differences between these respective groups were significant (p < 0.001). There was also an increasing trend of CD10 expression with increasing degree of malignancy and this trend was significant (p < 0.001).

One of the 33 fibroadenoma cases stained positively for CD10 in the stromal cells. Six of the 102 benign phyllodes tumour cases were positive, 16 of the 51 borderline malignant 51 were positive, and 14 of the 28 frankly malignant cases were positive (figs 1, 2). There was a significant increase in CD10 expression in the stromal cells as the lesions progressed from fibroadenomas and benign phyllodes tumours to tumours of borderline and frank malignancy (p < 0.001). Using one way ANOVA, there was an increasing trend of CD10 expression with increasing degree of malignancy, and this was also significant (p < 0.001). Table 1 summarises the results.

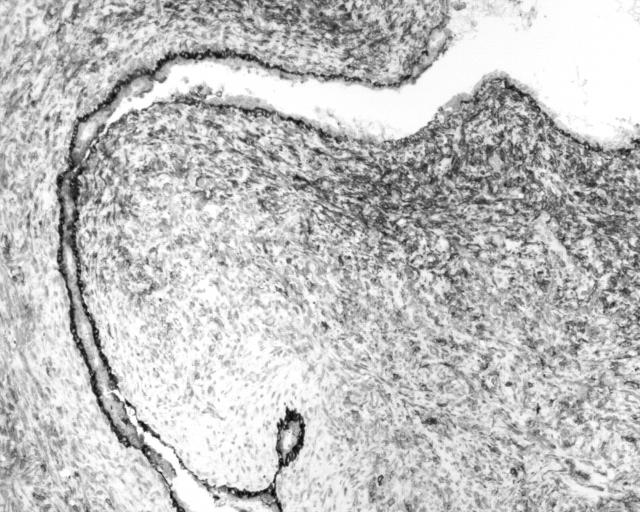

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph showing a malignant phyllodes tumour.

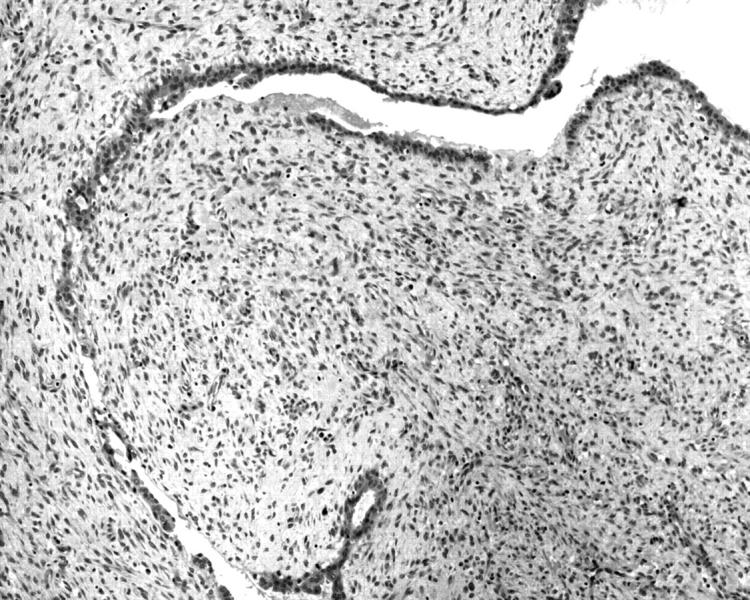

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of the same malignant phyllodes tumour showing positive cytoplasmic staining for CD10 in the stromal cells. Myoepithelial cells are also positive.

Table 1.

CD10 expression in fibroadenomas, benign, borderline malignant, and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours

| CD10 positive | CD10 negative | Total number | |

| Fibroadenoma | 1 (3.3%) | 32 (96.7%) | 33 |

| Phyllodes tumour, benign | 6 (5.9%) | 96 (94.1%) | 102 |

| Phyllodes tumour, borderline | 16 (31.4%) | 35 (68.6%) | 51 |

| Phyllodes tumour, malignant | 14 (50%) | 14(50%) | 28 |

Morphologically, the areas with the strongest staining were usually located subepithelially, and correlated with the areas with higher stromal cellularity and mitotic activity.

Of the 14 recurrent phyllodes tumours that were included in our series, the stromal expression of CD10 was variable, with six tumours being positive, whereas the remainder were negative. No association was found between CD10 expression and the number of recurrences, or whether or not there were metastases.

If these four groups of fibroepithelial lesions are divided into benign (encompassing fibroadenoma and benign phyllodes tumours) and malignant (borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours), using positive staining of stromal CD10 as a diagnostic criteria gives a specificity of 95%, positive predictive value of 81%, sensitivity of 38%, negative predictive value of 72%, and an accuracy of 74%.

DISCUSSION

CD10 (CALLA) is a cell surface neutral endopeptidase, and is expressed by lymphoid precursor cells and some B cells. Its expression has long been recognised in haematological malignancies. In non-haematological neoplasms, CD10 has been studied most extensively in endometrial stromal tumours, where it has been used in the differentiation of stromal tumours from smooth muscle tumours of the uterus. Some authors have reported good discriminatory ability of CD10,31 and its reliability as a sensitive marker for endometrial stroma.16 Other authors have found that CD10 expression in the endometrium is not limited to stromal lesions, with some expression seen in variants of leiomyoma, including highly cellular leiomyomas, epithelioid smooth muscle tumours, and the so called uterine tumours resembling ovarian sex cord tumours.32

“It is possible that, because CD10 belongs to the met alloprotease family, its increased expression may facilitate the metastatic potential of higher grade lesions by providing tumours with the capacity to invade vessel walls”

Reports on CD10 expression in the breast are scarce, but it has been reported in different cell types. In one study, CD10 was demonstrated in myoepithelial cells,6,20 apocrine metaplastic cells, and in situ adenocarcinoma.6 Among these cell populations, expression is strong in myoepithelial cells, and some authors have suggested using CD10 as a myoepithelial marker, particularly in problematic cases, as a means of detecting invasion.21 Authors of a recent paper33 have shown that CD10 expression is found in oestrogen receptor negative tumour cells, suggesting that these tumour cells show basal differentiation. In a novel report,22 CD10 expression seen in the stromal cells of invasive breast carcinoma was associated with an increased incidence of lymph node metastases. The expression of CD10 in the stromal cells of fibroepithelial lesions of the breast has only been reported in one small study in the literature.23 In that study, six of 13 fibroadenomas showed weak stromal CD10 staining, whereas all three phyllodes tumours showed weak to moderate stromal staining for CD10, and the single case of malignant phyllodes tumour showed the most intense staining, suggesting that CD10 expression is increased in phyllodes tumour development. Similarly, in our current study, which is the largest series of mammary phyllodes tumours investigated for CD10 expression in the stromal cells, a progressive increase in CD10 expression was seen in the stromal cells, from fibroadenoma to frankly malignant phyllodes tumours. Diagnosis of the different stages of malignancy in phyllodes tumour is based on a histological continuum, taking into account a combination of several histological parameters, rather than a discrete categorisation, and CD10 expression also highlights this continuous spectrum. There is also a histological overlap between benign phyllodes tumours and fibroadenoma, particularly the so called phyllodal variants and the intracanalicular variant, which has a superficial morphological resemblance to benign phyllodes tumours. We found that CD10 expression was low in both fibroadenoma and benign phyllodes tumours, and was much higher in borderline malignant and frankly malignant tumours, suggesting that benign phyllodes tumours may have a clinical pattern more similar to fibroadenoma than to borderline malignant or frankly malignant phyllodes tumours. This correlates with the clinical evidence that both borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours can metastasise, whereas benign phyllodes tumours and fibroadenomas do not metastasise.

We found that CD10 expression tended to occur in the subepithelial location, in the area of subepithelial stromal condensation, which is a focus of high proliferative activity.

Although the exact role of CD10 in the tumorigenesis and malignant transformation of phyllodes tumour remains unknown, it is possible that, because CD10 belongs to the met alloprotease family, its increased expression may facilitate the metastatic potential of higher grade lesions by providing tumours with the capacity to invade vessel walls. In support of this hypothesis, an interesting study22 showed that the increased expression of CD10 in stromal cells in invasive breast carcinoma was associated with increased lymph node metastases. It was postulated that CD10 expression might be induced by the cancer cells.22 A similar observation has also been made in colorectal carcinoma,34 in which stromal CD10 expression was significantly higher in severe dysplasia, intramucosal carcinoma, and invasive carcinoma than in adenomas with mild to moderate dysplasia. Furthermore, strong CD10 expression was detected only at the growth front of invasive carcinoma, and not in dysplastic lesions. In our study, whether the stronger stromal expression of CD10 in the higher grade phyllodes tumours was induced by other factors, as previously postulated,22 or was a primary event remains speculative and warrants further evaluation. However, the higher expression of CD10 in the stromal cells in the categories with an ability to metastasise (borderline and malignant groups) could be an important observation that may have diagnostic and prognostic implications, because death is more likely to occur from metastases than from local recurrences. Nevertheless, in our series, the number of recurrent cases was small, because most of the lesions received adequate initial treatment, making it impossible to assess the relation of CD10 expression with tumour recurrence. However, this is an interesting and important issue that warrants further evaluation.

Take home messages.

We investigated CD10 expression in a large series of mammary fibroepithelial lesions, and found a significant increase in stromal cell CD10 expression as the lesions progressed from fibroadenomas and benign phyllodes tumours to borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours

Lesions with the ability to metastasise (borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours) showed greater CD10 expression than those without this ability (benign phyllodes tumours and fibroadenomas)

CD10 may be a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours

At the diagnostic level, several markers have been reported to be increasingly expressed in borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours, including p53,35,36 microvessel density,37 and c-kit.38 CD10 could also be used as an adjunct to aid in correctly assessing the degree of malignancy in phyllodes tumours. Based on the widely used criteria, only the benign and frankly malignant groups of phyllodes tumours were well defined,29 and the defining features of the borderline malignant category remain highly variable, so that this group more or less includes all cases that do not fulfil the criteria at both the benign and malignant ends of the spectrum. This is well illustrated in the quoted percentage of borderline malignant lesions in different large series, with the percentage ranging from 11% to 42%.39–44 Stromal cell CD10 expression gives a high specificity and positive predictive value for predicting malignancy in phyllodes tumours, and can be used for the prediction of high or low metastatic risk, particularly if used as part of a panel of markers for the assessment, hence allowing the institution of adequate treatment.

In summary, we have shown that in a large series of mammary fibroepithelial lesions, there is a progressive and significant increase in stromal cell CD10 expression. It appears that lesions with the ability to metastasise (borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours) show much greater CD10 expression than those without this ability (benign phyllodes tumours and fibroadenomas). CD10 may be useful in assisting in the diagnosis of borderline and frankly malignant phyllodes tumours.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greaves MF, Brown G, Rapson NT, et al. Antisera to acute lymphoblastic leukaemia cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1975;4:67–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greaves MF, Hariri G, Newman RA, et al. Selective expression of the common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (gp 100) antigen on immature lymphoid cells and their malignant counterparts. Blood 1983;61:628–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss LM, Bindl JM, Picozzi VJ, et al. Lymphoblastic lymphoma: an immunophenotype study of 26 cases with comparison to T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Blood 1986;67:474–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein H, Lennert K, Feller AC, et al. Immunohistological analysis of human lymphoma: correlation of histological and immunological categories. Adv Cancer Res 1984;42:67–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregory CD, Tursz T, Edwards CF, et al. Identification of a subset of normal B cells with a Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL)-like phenotype. J Immunol 1987;139:313–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu P, Arber DA. Paraffin section detection of CD10 in 505 nonhematopoietic neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol 2000;113:374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Droz D, Zachar D, Charbit L, et al. Expression of the human nephron differentiation molecules in renal cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol 1990;137:895–905. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avery AK, Beckstead J, Renshaw AA, et al. Use of antibodies to RCC and CD10 in the differential diagnosis of renal neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dragovic T, Sekosan M, Becker RP, et al. Detection of neutral endopeptidase 24.11 (neprilysin) in human hepatocellular carcinomas by immunocytochemistry. Lab Invest 1994;70:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao SY, Wang HL, Hart J, et al. cDNA arrays and immunohistochemistry identification of CD10/CALLA expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2001;159:1415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato Y, Itoh F, Hinoda Y, et al. Expression of CD10/neutral endopeptidase in normal and malignant tissues of the human stomach and colon. J Gastroenterol 1996;31:12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrel S, De Tribolet N, Gross N. Expression of HLA–DR and common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia antigens on glioma cells. Eur J Immunol 1982;12:354–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brox AG, Lavallee MC, Arseneau J, et al. Expression of common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia-associated antigen on germ cell tumour. Am J Med 1986;80:1249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imai K, Kanzaki H, Fujiwara H, et al. Expression of aminopeptidase N and neutral endopeptidase on the endometrial stromal cells in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum Reprod 1992;7:1326–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanitakis J, Bourchany D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD10 antigen (neutral endopeptidase) by mesenchymal tumours of the skin. Anticancer Res 2000;20:3539–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, Maxwell P. CD10 is a sensitive and diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker of normal endometrial stroma and of endometrial stromal neoplasms. Histopathology 2001;39:273–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu PG, Arber DA, Weiss LM, et al. Utility of CD10 in distinguishing between endometrial stromal sarcoma and uterine smooth muscle tumours: an immunohistochemical comparison of 34 cases. Mod Pathol 2001;14:465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toki T, Shimizu M, Takagi Y, et al. CD10 is a marker for normal and neoplastic endometrial stromal cells. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikami Y, Hata S, Kiyokawa T, et al. Expression of CD10 in malignant mullerian mixed tumours and adenosarcomas: an immunohistochemical study. Mod Pathol 2002;15:923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahendran R, McIlhinney R, O’Hare M, et al. Expression of the common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia antigen (CALLA) in the human breast. Mol Cell Probes 1989;3:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moritani S, Kushima R, Sugihara H, et al. Availability of CD10 immunohistochemistry as a marker of breast myoepithelial cells on paraffin sections. Mod Pathol 2002;15:397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwaya K, Ogawa H, Izumi M, et al. Stromal expression of CD10 in invasive breast carcinoma: a new predictor of clinical outcome. Virchows Arch 2002;440:589–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mechtersheimer G, Kruger KH, Born IA, et al. Antigenic profile of mammary fibroadenoma and cystosarcoma phyllodes. A study using antibodies to estrogen and progesterone receptors and to a panel of cell surface molecules. Pathol Res Pract 1990;186:427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azzopardi JG. Sarcoma of the breast. In: Bennington J, ed. Problems in breast pathology, Vol. II, Major problems in pathology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1979:355–9.

- 25.Palmer ML, De Risi DC, Pelikan A, et al. Treatment options and recurrence potential for cystosarcoma phyllodes. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1990;170:193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kario K, Meada S, Mizuno Y, et al. Phyllodes tumour of the breast: a clinocopathologic study of 34 cases. J Surg Oncol 1990;45:46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowell MD, Perry RR, Hsiu JG, et al. Phyllodes tumours. Am J Surg 1993;165:376–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole–Beuglet C, Soriano R, Kurtz AB, et al. Ultrasound, X–ray mammography and histopathology of cystosarcoma phyllodes. Radiology 1983;146:481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen PP. Fibroepithelial neoplasms. In: Breast pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott–Raven, 2000:176–97.

- 30.Tse GM, Putti TC, Kung FY, et al. Increased p53 protein expression in malignant mammary phyllodes tumours. Mod Pathol 2002;15:734–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu XQ, Shi YF, Cheng XD, et al. Immunohistochemical markers in differential diagnosis of endometrial stromal sarcoma and cellular leiomyoma. Gynecol Oncol 2004;92:71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliva E, Young RH, Amin MB, et al. An immunohostochemical analysis of endometrial stromal and smooth muscle tumours of the uterus. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:403–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kesse–Adu R, Shousha S. Myoepithelial markers are expressed in at least 29% of oestrogen receptor negative invasive breast carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2004;17:646–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogawa H, Iwaya K, Izumi M, et al. Expression of CD10 by stromal cells during colorectal tumor development. Hum Pathol 2002;33:806–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Millar EK, Beretov J, Marr P, et al. Malignant phyllodes tumours of the breast display increased stromal p53 protein expression. Histopathology 1999;34:491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tse GM, Ma TK, Chan KF, et al. Increased microvessel density in malignant and borderline mammary phyllodes tumours. Histopathology 2001;38:567–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tse GM, Lui PC, Scolyer RA, et al. Tumour angiogenesis and p53 protein expression in mammary phyllodes tumours. Mod Pathol 2003;16:1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tse GM, Putti TC, Lui PC, et al. Increased c-kit (CD117) expression in malignant mammary phyllodes tumours. Mod Pathol 2004;17:827–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niezabitowski A, Lackowska B, Rys J, et al. Prognostic evaluation of proliferative activity and DNA content in the phyllodes tumour of the breast: immunohistochemical and flow cytometric study of 118 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;65:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuenen–Boumeester V, Henzen–Logmans SC, Timmermans MM, et al. Altered expression of p53 and its regulated proteins in phyllodes tumours of the breast. J Pathol 1999;189:169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shabalova IP, Chemeris GJ, Ermilova VD, et al. Phyllodes tumour: cytologic and histologic presentation of 22 cases, and immunohistochemical demonstration of p53. Cytopathology 1997;8:177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suo Z, Nesland JM. Phyllodes tumour of the breast: EGFR family expression and relation to clinicopathological features. Ultrastruct Pathol 2000;24:371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinfuss M, Mitus J, Duda K, et al. The treatment and prognosis of patients with phyllodes tumour of the breast: an analysis of 179 cases. Cancer 1996;77:910–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohn–Cedermark G, Rutqvist LE, Rosendahl I, et al. Prognostic factors in cystosarcoma phyllodes. A clinicopathologic study of 77 patients. Cancer 1991;68:2017–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]