Abstract

Myeloid sarcomas are extramedullary tumours with granulocytic precursors. When associated with acute myelogenous leukaemia (AML), these tumours usually affect no more than two different extramedullary regions. This report describes a myeloid sarcoma associated with AML with tumour formation at five anatomical sites. The patient was a 37 year old man admitted in September 1999 with a two month history of weight loss, symptoms of anaemia, rectal bleeding, and left facial nerve palsy. The anatomical sites affected were: the rectum, the right lobe of the liver, the mediastinum, the retroperitoneum, and the central nervous system. A bone marrow smear was compatible with AML M2. Flow cytometry showed that the peripheral blood was positive for CD4, CD11, CD13, CD14, CD33, CD45, and HLA-DR. A karyotypic study of the bone marrow revealed an 8;21 translocation. The presence of multiple solid tumours in AML is a rare event. Enhanced expression of cell adhesion molecules may be the reason why some patients develop myeloid sarcomas.

Keywords: acute myelogenous leukaemia, myeloid sarcoma

Myeloid sarcoma, formerly known as granulocytic sarcoma,1 was described by Rappaport in 1966.2 It is an extramedullary solid tumour composed of myeloblasts and other granulocytic precursors, with or without an associated haematological malignancy.3 This tumour was originally referred to as chloroma, because of its green colour, secondary to the presence of myeloperoxidase.4 Single myeloid sarcomas are present in about 2% of patients with acute myelogenous leukaemia (AML). The diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma can be difficult. Traweek advised the use of immunohistochemical staining of paraffin wax embedded tissue sections, using antibodies to CD20, CD33, CD68, and myeloperoxidase, and reported an accuracy of 96%.5 In most patients, myeloid sarcoma associated with AML affects no more than two sites. We report a highly unusual patient with multifocal tumours affecting five different anatomical sites, namely: the rectum, the right lobe of the liver, the mediastinum, the kidney, and the brain.

“The diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma can be difficult”

CASE REPORT

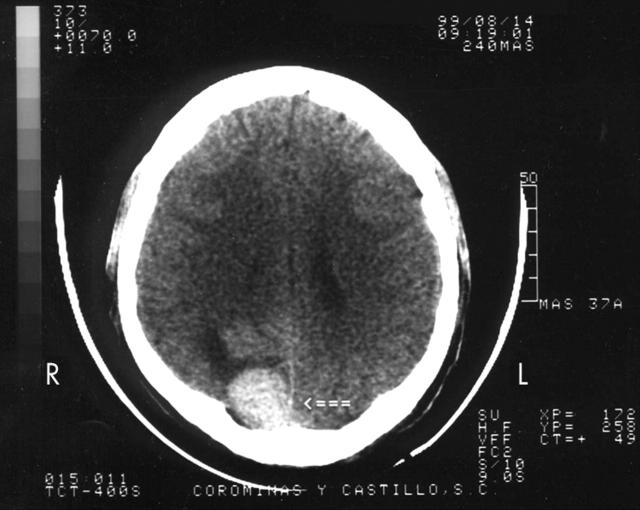

A 37 year old man was admitted in September 1999 with a two month history of weight loss, symptoms of anaemia, and rectal bleeding. On examination, he appeared pale, underweight, and tachycardic, with petechiae and ecchymosis on the lower limbs. Fundoscopic examination showed bilateral papilloedema and several retinal flame haemorrhages. A seventh left cranial nerve lesion was found. The liver edge was 5 cm below the right costal border. Laboratory studies showed a haemoglobin concentration of 45 g/litre, white blood cell count of 4.1 × 109/litre, platelet count of 50 × 109/litre, and 35% blast cells; some blast cells contained Auer rods. Lactate dehydrogenase was 12 931 IU/litre (normal range, 91–180). Chest radiography showed mediastinal expansion. Computed tomography of the brain showed a solitary hyperdense subdural nodule, 2.9 cm in diameter in the occipital region (fig 1). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed a solid mass, 10 cm in diameter, with regular edges and central hypodensity, compatible with necrosis of the right lobe of the liver. The liver–kidney space was occupied by tumour. The left kidney showed a 4 cm tumour mass. The rectum and sigmoid were infiltrated by an irregular 8 cm diameter tumour (fig 2A, B).

Figure 1.

Brain computed tomography scan showing a solitary mass at the right occipital region, indicated by a closed arrow.

Figure 2.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography scan showing a solid tumour with hypodensities suggestive of necrosis in the hepatorenal space and retroperitoneal cavity, causing a compression effect against the right kidney. (B) Pelvic computed tomography scan showing the presence of a solid tumour at the rectum–sigmoid level, with hypodensities indicated by the numbers 1, 2, and 3.

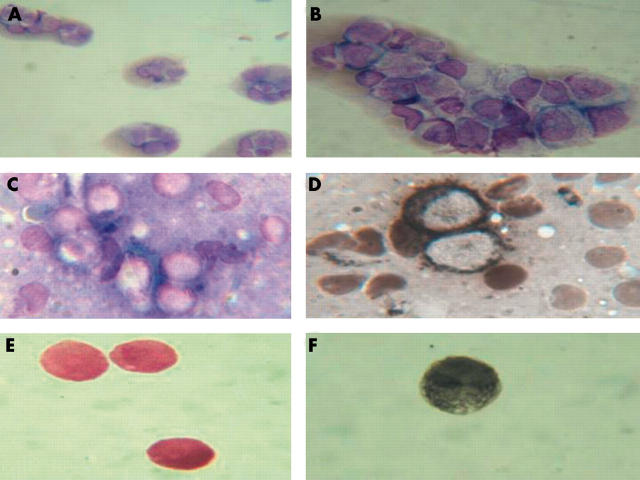

Bone marrow aspiration was compatible with AML M2 (fig 3A, B). Flow cytometry showed that the peripheral blood was positive for CD4, CD11, CD13, CD14, CD33, CD45, and HLA-DR. A bone marrow karyotypic study revealed a 8;21 translocation. A percutaneous ultrasound guided biopsy of the mass anterior to the right kidney was done. A touch preparation showed abundant Sudan black positive myeloblasts (some with Auer rods) (fig 3C, D). The cerebral spinal fluid contained Sudan black and myeloperoxidase positive myeloblasts (fig 3E, F).

Figure 3.

(A) Low power view of a bone marrow smear (Wright stain) showing a clump of myeloblasts; original magnification, ×40. (B) High power view of a bone marrow smear (Wright stain) showing a clump of myeloblasts; original magnification, ×100. (C) High power view of a touch preparation of the pararenal tumour mass (Wright stain); original magnification, ×100. (D) Touch preparation of the pararenal tumour mass showing Sudan black positive myeloblasts. (E) Cerebrospinal fluid smear showing myeloblast infiltration (Wright stain). (F) Cerebrospinal fluid smear showing myeloblast infiltration (Sudan black stain).

The patient received combination chemotherapy and craniospinal radiotherapy, and achieved complete haematological remission, which was maintained for 18 months. Despite an allogeneic bone marrow transplant, he subsequently relapsed and at relapse had myeloid sarcomas in the inferior pole of the right kidney, at the right ureterovesical junction, and the rectum.

DISCUSSION

Myeloid sarcoma is an extramedullary tumour composed of granulocyte precursors.2 It is frequently found in bones, peritoneum, lymph nodes, skin, and epidural structures.6 Myeloid sarcoma in patients with t(8;21) was first reported in 1984 by Swirsky et al, who found that seven of 30 patients with t(8;21) had solid leukaemic deposits, principally in the mastoid, orbital cavities, or thoracic spine (extradural).7 Because myeloid sarcoma can be seen in the absence of AML, evaluation of unusual tumours by immunohistochemical staining for CD33, CD68, and myeloperoxidase is advised.5

“The presence of neural cell adhesion molecule on the surface of blast cells has been shown to enhance their propensity for tissue penetration into the central nervous system”

Solid tumour masses are uncommon in AML and their presence might be attributable to overexpression of cell adhesion molecules. The presence of neural cell adhesion molecule on the surface of blast cells has been shown to enhance their propensity for tissue penetration into the central nervous system, in particular into the cerebellum.8 Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation has been advocated in patients with a solitary myeloid sarcoma,9 but was not of longterm benefit in our patient with AML and multiple myeloid sarcomas.10

Take home messages.

We describe an unusual case of myeloid sarcoma associated with acute myelogenous leukaemia (AML) with tumour formation at five anatomical sites

The anatomical sites affected were: the rectum, the right lobe of the liver, the mediastinum, the retroperitoneum, and the central nervous system

The presence of multiple solid tumours in AML is rare

The development of myeloid sarcomas may be associated with enhanced expression of cell adhesion molecules

Abbreviations

AML, acute myelogenous leukaemia

The patient gave his permission for this case report to be published

REFERENCES

- 1.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasmas. Blood 2002;100:2292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rappaport H . Tumors of the hematopoietic system. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, Section 3, Fascicle 8. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1966:241–43.

- 3.Lin PI, Ishimani T, McGregor DH, et al. Autopsy study of granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) in patients with myelogenous leukemia. Hiroshima-Nagasaki 1949–1969. Cancer 1973;31:948–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alama Zaragoza MA, Robles Iniesta A, Roca Adelanatado I, et al. Hepatic granulocytic sarcoma: an unusual presentation. An Med Interna 2003;20:141–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traweek ST, Arber DA, Rappaport H, et al. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors: an immunohistochemical and morphologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:1011–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sisack MJ, Dunsmore K, Sidhu-Malik N. Granulocytic sarcoma in absence of myeloid leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:308–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swirsky DM, Li YS, Matthews JG, et al. 8;21 translocation in acute granulocytic leukaemia: cytological, cytochemical and clinical features. Br J Haematol 1984;56:199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neiman RS, Barcos M, Berald C, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer 1981;48:1426–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psiachou-Leonard E, Paterakis G, Stefanaki K, et al. Cerebellar granulocytic sarcoma in an infant with CD56+ acute monoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res 2001;25:1019–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imrie KR, Kovacs MJ, Selby D, et al. Isolated chloroma: the effect of early antileukemic therapy. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:351–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]