Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas are rare, and atypical features might lead to diagnostic pitfalls. This report describes an unusual patient in whom lymphoma occurred initially as isolated lymph node involvement, an exceptional presentation of an almost exclusively extranodal disease. Furthermore, during the terminal haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, lymphoma cells lost the expression of the NK cell marker, CD56, making the histopathological diagnosis of bone marrow involvement difficult. This was resolved by in situ hybridisation for Epstein-Barr virus encoded small RNA, which detected occult bone marrow infiltration.

Keywords: CD56, Epstein-Barr virus encoded early small RNA, natural killer cell lymphoma, nodal

Lymphomas derived from natural killer (NK) cells have been classified as a distinct entity in the recently proposed World Health Organisation classification of haematolymphoid malignancies.1–4 NK cell lymphomas exhibit a broad morphological spectrum, with angiocentricity and zonal tumour necrosis frequent but not invariable histological features. Furthermore, there is an almost invariable presence of Epstein Barr virus (EBV) infection in the tumour cells, which can be detected by in situ hybridisation (ISH) for EBV encoded early small RNAs (EBERs).1–4 EBV clonality can be shown by molecular analysis of the EBV terminal repeats.2,3 Immunophenotypically, the lymphoma cells classically express CD2, cytoplasmic CD3ɛ (but not surface CD3), and CD56. Therefore, NK cell lymphomas show a characteristic profile of CD2+, CD3ɛ+, CD56+, EBER+.5

“Because of their rarity, natural killer cell lymphomas are challenges even to the experienced pathologist”

Clinically, NK cell lymphomas often involve the nasal or paranasal areas, and are referred to as nasal NK cell lymphomas.4,6 They can also occur at extranasal sites, including the skin, testis, gastrointestinal tract, and parotid glands, and are referred to as nasal-type NK cell lymphomas.7–9 Rarely, the lymphoma can be disseminated with multiorgan involvement at diagnosis, and is referred to as NK cell lymphoma/leukaemia.8,10 Because primary nodal presentation is highly unusual, the lymphoma is aptly referred to as extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type, in the World Health Organisation classification.1

Because of their rarity, NK cell lymphomas are challenges even to the experienced pathologist. Therefore, exceptional features need to be reported and discussed because they may constitute diagnostic pitfalls to the unwary.

CASE REPORT

A 59 year old man presented with intermittent fever, night sweating, and left submandibular swelling. The submandibular lymph node biopsy showed partial replacement by a polymorphic infiltration of small to medium sized abnormal lymphoid cells with a prominent eosinophilic infiltrate. Focal angioinvasion by the abnormal lymphoid infiltrate was identified (fig 1A, B). The abnormal lymphoid cells were CD2+, surface CD3−, CD3ɛ+, and CD56+ (fig 1C). EBER was strongly positive on ISH (fig 1D). Polymerase chain reaction for the T cell receptor gene showed a germline configuration. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of NK cell lymphoma. To search for occult nasopharyngeal involvement, endoscopy of the nasopharynx with random biopsies was performed, but lymphoma was not seen. The serum lactate dehydrogenase concentration was increased to 640 U/litre (normal, < 400). Real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction11 showed circulating plasma EBV DNA to be 1.4 × 103 copies/ml at diagnosis. Further investigations showed no involvement of other anatomical sites. The diagnosis was therefore primary nodal NK cell lymphoma, Ann Arbor stage 1B. The patient achieved complete remission with three courses of combination chemotherapy, which was consolidated with local radiotherapy. He remained well until two years later when he developed a refractory left leg ulcer associated with enlarged left inguinal lymph nodes. Biopsy of the leg ulcer confirmed recurrent NK cell lymphoma. There was no apparent involvement of other sites. He received cisplatinum, high dose cytosine arabinoside, and dexamethasone, together with local irradiation to the leg ulcer. The response was poor, and despite chemotherapy, he developed persistent fever, hepatosplenomegaly, nodular lesions over the trunk and limbs, and pancytopenia (haemoglobin, 84 g/litre; platelets, 46 × 109/litre; and white blood cell count, 1.2 × 109/litre). Lactate dehydrogenase was extremely high at 5640 U/litre. Bone marrow aspiration showed scattered atypical lymphoid cells with prominent haemophagocytosis. Immunohistochemical analysis did not reveal CD56+ cells (fig 2A–C), although ISH showed multiple EBER positive lymphoid cells (fig 2D). Computerised tomography of the thorax and abdomen showed mediastinal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. He deteriorated rapidly and died. A postmortem examination was not permitted by the family.

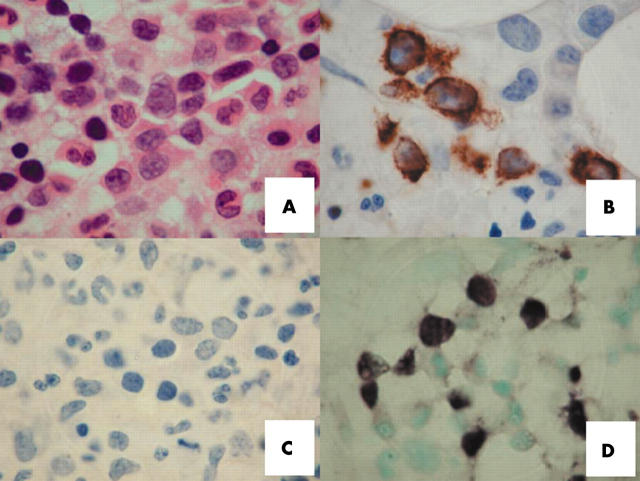

Figure 1.

Histopathology of a case of nodal natural killer cell lymphoma. (A) Lymph node biopsy, showing interfollicular areas expanded by abnormal lymphoid cells with angioinvasion (haematoxylin eosin (H&E) stain; original magnification, ×40). (B) The neoplastic lymphoid cells were small to medium in size, with prominent eosinophilic infiltration (H&E stain; original magnification, ×200). (C) Immunostaining for CD56, showing abundant positive lymphoma cells (original magnification, ×200). (D) In situ hybridisation for Epstein-Barr virus encoded early small RNA, showing numerous positive cells (original magnification, ×200).

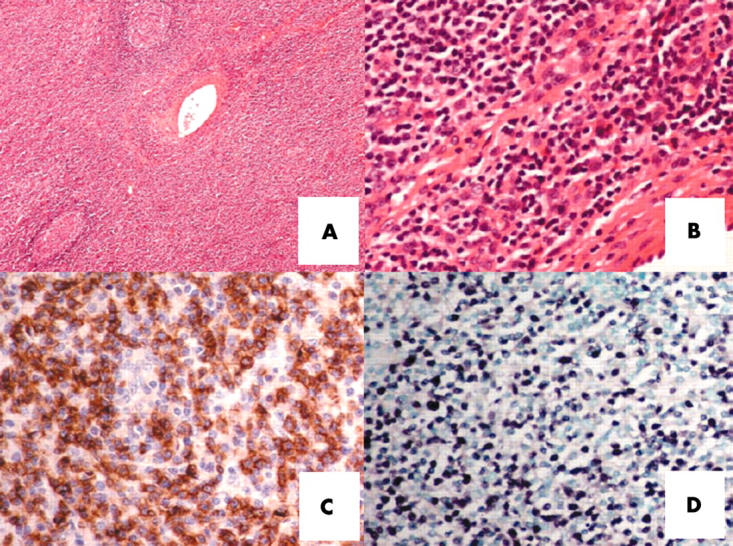

Figure 2.

Histopathological features of bone marrow infiltration in relapsed natural killer cell lymphoma. (A) Trephine biopsy showing an interstitial infiltrate of abnormal lymphoid cells. They were large in size, having coarse chromatin texture, 1–3 small nucleoli, and an appreciable amount of cytoplasm (haematoxylin eosin stain; original magnification, ×1000). (B) Immunostaining for CD3, showing positive cells (original magnification, ×1000). (C) Immunostaining for CD56, showing no positive cells (original magnification, ×1000). (D) In situ hybridisation for Epstein-Barr virus encoded early small RNA, showing clusters of positive lymphoma cells.

DISCUSSION

This case showed some extraordinary features. First, the lymphoma initially presented as the isolated involvement of a lymph node, which is exceptional. In a review of 45 cases of nasal-type (extranasal) CD56 positive lymphomas, only one had primary nodal presentation, but this patient had concurrent bone marrow involvement.8 In another series of 13 aggressive nodal T and NK/T cell lymphomas, only one had a classic NK cell lymphoma profile (CD2+, CD3−, CD56+, EBER+).12 The low copy number of plasma EBV DNA at presentation (1.4 × 103 copies/ml, compared with 105 to 1010 copies/ml for nasal and non-nasal NK cell lymphomas11) also supported isolated lymph node involvement. However, other than the rare nodal presentation, this case showed pathological and molecular features that were typical of NK cell lymphoma. Furthermore, the terminal dissemination to the skin, liver, spleen, and bone marrow is also common in extranodal nasal or nasal-type NK cell lymphomas.4,8

Take home messages.

We describe an unusual patient in whom natural killer (NK) cell lymphoma occurred initially as isolated lymph node involvement, an exceptional presentation of an almost exclusively extranodal disease

During the terminal haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, lymphoma cells lost the expression of the NK cell marker, CD56, making the histopathological diagnosis of bone marrow involvement difficult

This was resolved by in situ hybridisation for Epstein-Barr virus encoded small RNA, which detected occult bone marrow infiltration

“CD56 should not be relied upon alone as a marker of neoplastic natural killer cells”

During the terminal phase of illness, our patient showed peripheral blood pancytopenia with prominent bone marrow haemophagocytosis. From a diagnostic viewpoint, the distinction between haemophagocytosis and lymphomatous infiltration as a cause of the pancytopenia might not be easy. Haemophagocytosis occurs commonly in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow in NK cell lymphomas. It may be reactive, and is itself not necessarily an indicator of infiltration in the involved tissue.7,8,10 Furthermore, NK cell lymphoma infiltration might be patchy and inconspicuous. Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 offers a diagnostic aid to identifying the lymphomatous cells.1 However, a notable caveat is that the expression of CD56 on the lymphoma cells might occasionally be lost at relapse.13 This phenomenon was again seen in our patient, highlighting the important point that CD56 should not be relied upon alone as a marker of neoplastic NK cells.

This problem was overcome by the use of EBER-ISH. In fact, EBER-ISH has been shown to be more sensitive than CD56 immunostaining in detecting occult bone marrow infiltration by NK cell lymphoma.14 Other ancillary markers such as cytotoxic granule associated proteins (granzyme B, TIA-1, and perforin), expressed in NK cell lymphoma but rarely in other lymphomas, might also be helpful,1 although their use has not been formally compared with EBER-ISH.

In conclusion, our case showed that NK cell lymphoma can present atypically in the lymph node, and that both immunohistochemical staining and EBER-ISH are necessary in the histopathological diagnosis.

Abbreviations

EBER, Epstein-Barr virus encoded early small RNA

EBV, Epstein-Barr virus

ISH, in situ hybridisation

NK, natural killer

Full permission was given for this case report to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the clinical advisory committee meeting. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3835–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siu LL, Chan JK, Kwong YL. Natural killer cell malignancies: clinicopathologic and molecular features. Histol Histopathol 2002;17:539–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwong YL, Chan AC, Liang RH. Natural killer cell lymphoma/leukemia: pathology and treatment. Hematol Oncol 1997;15:71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chim CS, Ma SK, Au WY, et al. Nasal NK-cell lymphoma: long-term treatment outcome and validity of the IPI index. Blood 2004;103:216–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffe ES, Chan JKC, Su IH, et al. Report of the workshop on nasal and related extranodal angiocentric T/natural killer cell lymphoma. Definitions, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chim CS, Ooi GC, Shek WH, et al. Lethal midline granuloma revisited: nasal T/NK cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1322–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chim CS, Shek TW, Ho J, et al. Primary CD56+ gastrointestinal lymphoma. Cancer 2001;91:525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan JKC, Sin VC, Wong KF, et al. Nonnasal lymphoma expressing the natural killer cell marker CD56: a clinicopathologic study of 49 cases of an uncommon aggressive neoplasm. Blood 1997;89:4501–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chim CS, Au WY, Loong F, et al. Primary NK-cell lymphoma of the skeletal muscle. Histopathology 2002;41:371–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwong YL, Chan ACL, Liang R, et al. CD56+ NK lymphoma: two distinct subtypes with different clinicopathologic features and prognosis. Br J Haematol 1997;97:821–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Au WY, Pang A, Choy C, et al. Quantification of circulating Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA in the diagnosis and monitoring of natural killer cell and EBV-positive lymphomas in immunocompetent patients. Blood 2004;104:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagami Y, Suzuki R, Taji H, et al. Nodal cytotoxic lymphoma spectrum: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1184–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siu LL, Chan JK, Wong KF, et al. Aberrant promoter CpG methylation as a molecular marker for disease monitoring in natural killer cell lymphomas. Br J Haematol 2003;122:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong KF, Chan JK, Cheung MM, et al. Bone marrow involvement by nasal NK cell lymphoma at diagnosis is uncommon. Am J Clin Pathol 2001;115:266–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]