Abstract

A previously healthy 11 year old boy died unexpectedly after a rapid course of progressive pneumonia. Postmortem microbiology and histopathology suggested an underlying diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease. This was confirmed by neutrophil oxidative burst and gene mutation analysis of other family members, one of whom benefited from early bone marrow transplantation.

Keywords: chronic granulomatous disease, Burkholderia cepacia, palatal granulomatous mucositis, autoimmunity

An 11 year old boy was admitted to hospital with right upper lobe pneumonia. Two weeks earlier he presented to his general practitioner with several days’ history of fever, cough, and malaise. He was prescribed amoxicillin, followed after a week by erythromycin.

Previous to this he had been healthy, except for an unusual, butterfly shaped, pigmented, indolent palatal lesion present for many years (fig 1). Because of this his dentist referred him at the age of 6 years to the oral surgeons who had noticed “somewhat hyperplastic palatal tissue that looked like a chronic candidiasis but with peculiar distribution”. However, no swabs were taken and no biopsy was performed at the time.

Figure 1.

The unusual, butterfly shaped, pigmented, indolent palatal lesion that was present for many years in our patient.

After admission to hospital, he was started on intravenous penicillin and erythromycin but remained febrile and unwell. By day 4 he became lethargic, developed diarrhoea, progressive liver failure, leucopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Repeat chest radiography showed extension of pneumonia to the entire right lung, and ultrasound demonstrated pleural and pericardial effusions. Antibiotics were changed to ciprofloxacin and cefuroxime and he was transferred to a paediatric intensive care unit. Despite aggressive supportive care he died within 12 hours of transfer from overwhelming septic shock and multiorgan failure. Antemortem sputum and blood cultures had been negative.

The patient’s deterioration while on appropriate treatment for community acquired pneumonia suggested the involvement of an unusual organism.1 Indeed, postmortem cultures (blood, lungs, liver, and spleen) grew Burkholderia cepacia. The presence of this well known, opportunistic pathogen found in individuals with pre-existing respiratory epithelial damage (such as patients with cystic fibrosis) suggested an underlying neutrophil disorder.2 The granulomatous inflammation of the lungs, liver, and spleen seen on postmortem histopathology further supported this possibility.

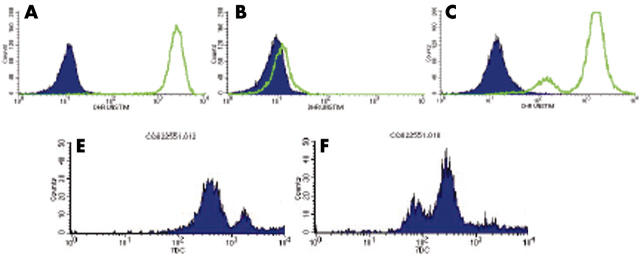

Unfortunately, because of the fulminant disease course, no immunological investigations were performed before death. However, 20% of the mother’s neutrophils had reduced oxidative burst activity, suggesting a carrier state for X linked chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) (fig 2C). Consequently, the mother’s sister’s 4 year old son, who was being investigated at the time for the cause of recurrent ear infections, intermittent colitis, and reduced energy levels, came to our attention. His neutrophil oxidative burst activity was absent (fig 2B). A C189G mutation in the CYBB gene on the X chromosome, predicting Asn63Lys substitution in the gp-91phox component of leucocyte NADPH oxidase, confirmed the diagnosis of X linked CGD and a heterozygous state in both mothers.3 He has since successfully undergone bone marrow transplantation from a human leucocyte antigen matched sibling.

Figure 2.

Neutrophil oxidative burst activity; neutrophil counts (y axis) and log scale of arbitrary units of fluorescence (x axis). (A–C) Before (shaded) and after (unshaded area) stimulation of neutrophils loaded with dihydrorodamine (DHR) with phorbol myristate acetate. (A) Increased fluorescence of all neutrophils in a healthy person (father). (B) No increase in fluorescence on stimulation suggesting chronic granulomatous disease (CGD; affected cousin). (C) Most neutrophils responding to stimulation with increased fluorescence, with a shoulder of less responsive neutrophils suggesting X linked CGD carrier status (identical for mother and her sister). (D,E) Staining of neutrophils with monoclonal antibody 7D5 specific for gp-91phox.3 (D) Two peaks shown by the normal control (the higher peak represents high gp-91phox expression by eosinophils). (E) Three peaks shown by the carrier (mother): the “negative” peak (gp-91phox negative neutrophils), the “positive” peak (gp-91phox positive neutrophils), and the higher “positive” peak (eosinophils). The low oxidase activity seen in the DHR test in both carriers can be explained by the carryover of hydrogen peroxide from the normal cells to the oxidase negative cells, which leads to some DHR oxidation inside the oxidase negative cells. The 7D5 monoclonal antibody test confirms the existence of gp-91phox negative and gp-91phox positive neutrophils, suggesting that this mutation in CYBB prevents gp-91phox expression.

DISCUSSION

The clinical, genetic, and biochemical features of CGD were recently reviewed.4 Children with the X linked disease classically present during the 1st year of life with recurrent, life threatening bacterial and fungal infections. In patients with the variant form of the X linked disease (not absent but reduced gp-91phox function), the diagnosis may not be made for many years.5 However, features of the neutrophil oxidative burst, with a mosaic of oxidase positive and negative neutrophils on dihydrorodamine staining in the two carrier sisters, confirmed by gp-91phox expression analysis (fig 2E), suggest that this mutation in the CYBB gene prevents gp-91phox expression.

“Chronic granulomatous disease is still associated with high morbidity and mortality, but recent encouraging results of haemopoietic stem cell transplantation suggest that this treatment may be curative”

The infrequent and variable oral manifestations of CGD include aphthous stomatitis, mucosal ulcers, granulomatous cheilitis, palatal granulomatous mucositis, and enamel hypoplasia.6 This abnormal granulomatous inflammatory response is a direct consequence of inefficient killing by phagocytes as a result of their reduced oxidative metabolism.7 In addition, polymorphism of host defence molecules and proinflammatory cytokines has been highlighted8 as another factor for the unexpected autoimmune response9 that can occur in affected individuals.10

Since the initial description of CGD in the 1950s as “fatal granulomatosis of childhood”, the survival and quality of life has substantially improved as a result of good conservative care, infection prevention, and aggressive surgical treatment. However, CGD is still associated with high morbidity and mortality, but recent encouraging results of haemopoietic stem cell transplantation suggest that this treatment may be curative.11

Important teaching points.

An infection caused by an uncommon organism may be responsible for the lack of response to the usual line of treatment

Finding of an unusual organism causing infection in an otherwise healthy individual should raise the suspicion of primary immunodeficiency, which, occasionally, may present with an unusual clinical feature and/or after many apparently healthy years

The peculiar physical signs usually have an underlying pathophysiology and one should persevere in trying to explain the unusual and unexpected

Once the diagnosis of a primary immunodeficiency is made, even after death of the patient in question, screening of the extended family is important because other affected members may be diagnosed and benefit from currently available treatment(s)

Abbreviations

CGD, chronic granulomatous disease

Consent was obtained from the parents of the child presented in this case report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Russell G. Community acquired pneumonia. Arch Dis Child 2001;85:445–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakshman R, Finn A. Neutrophil disorders and their management. J Clin Pathol 2001;54:7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamauchi A, Yu L, Pötgens AJ, et al. Location of the epitope for 7D5, a monoclonal antibody raised against human flavocytochrome b558, to the extracellular peptide portion of primate gp91phox. Microbiol Immunol 2001;45:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal BH, Leto TL, Gallin JI, et al. Genetic, biochemical and clinical features of chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine 2000;79:170–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liese JG, Jendrossek V, Jansson A, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease in adults. Lancet 1995;346:220–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovas JGL, Issekutz A, Walsh N, et al. Lupus erythematosus-like oral mucosal and skin lesions in a carrier of chronic granulomatous disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995;80:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves EP, Lu H, Jacobs HL, et al. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ influx. Nature 2002;416:291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster CB, Lehrnbecher T, Mol F, et al. Host defense molecule polymorphisms influence the risk for immune-mediated complications in chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Invest 1998;102:2146–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arkwright PD, Abinun M, Cant AJ. Autoimmunity in human primary immunodeficiency disease. Blood 2002;99:2694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badolato R, Notarangelo LD, Plebani A, et al. Development of systemic lupus erythematosus in a young child affected with chronic granulomatous disease following withdrawal of treatment with interferon-gamma. Rheumatology 2003;42:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seger RA, Gungor T, Belohradsky BH, et al. Treatment of chronic granulomatous disease with myeloablative conditioning with an unmodified hemopoietic allograft: a survey of the European experience 1985–2000. Blood 2002;100:4344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]