Abstract

This case report describes an atypical case of duodenal leishmaniasis in an elderly patient not infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Investigation of this 84 year old woman with a constitutional syndrome and dysphagia revealed anaemia of chronic disorder, a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinaemia. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed thickening of the stomach wall, which was seen to be inflamed during gastroscopy. Duodenal histology revealed numerous leishmania amastigotes within macrophages. This was confirmed by bone marrow biopsy and leishmania serology. This case report stresses the importance of atypical symptoms and the unusual location of visceral leishmaniasis, not only in immunodepressed patients, but also in elderly immunocompetent patients.

Keywords: visceral leishmaniasis, elderly, human immunodeficiency virus, duodenal infection

Visceral leishmaniasis is a parasitosis of the mononuclear phagocytic system caused by the protozoan leishmania. Although it normally affects immunocompetent patients in endemic areas, the disease is often seen in immunodepressed patients, particularly those infected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1 Typical symptoms are fever, hepatosplenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinaemia, and pancytopenia,2 but it can also manifest itself atypically, mostly in patients infected with HIV and geriatric immunocompetent patients. We present an unusual duodenal leishmaniasis in an HIV negative elderly patient and also stress the importance of histological examination for reaching a diagnosis when there is no macroscopic evidence of infection.

CASE REPORT

The patient was an 84 year old woman who attended hospital for the investigation of anaemia and constitutional syndrome. She had a history of well controlled diabetes. She complained about asthenia, anorexia, and a weight loss of 4 kg in one month. She also reported dysphagia and odynophagia.

On physical examination she was afebrile and pale. No goiter, adenopathy, or inflammatory signs on temporal arteries were found. No abdominal mass or organ enlargement was detected.

Blood tests showed: haemoglobin, 89 g/litre; mean corpuscular volume, 76.2 fl; mean corpuscular haemoglobin, 25.4 pg; leucocytes, 3500 × 109/litre (61% neutrophils and 28% lymphocytes); total proteins, 89 g/litre; and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 107 mm/hour. At that point several diagnostic alternatives became evident: plasma cell tumours, gastrointestinal tumours, rheumatic diseases, or chronic infections. Posterior studies revealed anaemia of chronic diseases (iron, 360 μg/litre; ferritin, 914 μg/litre) and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinaemia (IgG, 2920; IgA, 4860 mg/litre). Calcium and bone series proved normal, paraprotein were not found in blood or urine, β2 microglobulin was 5.7 mg/litre (normal range, 1–3.2), and tumour markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, α fetoprotein, CA-125, and CA-19.9) were negative.

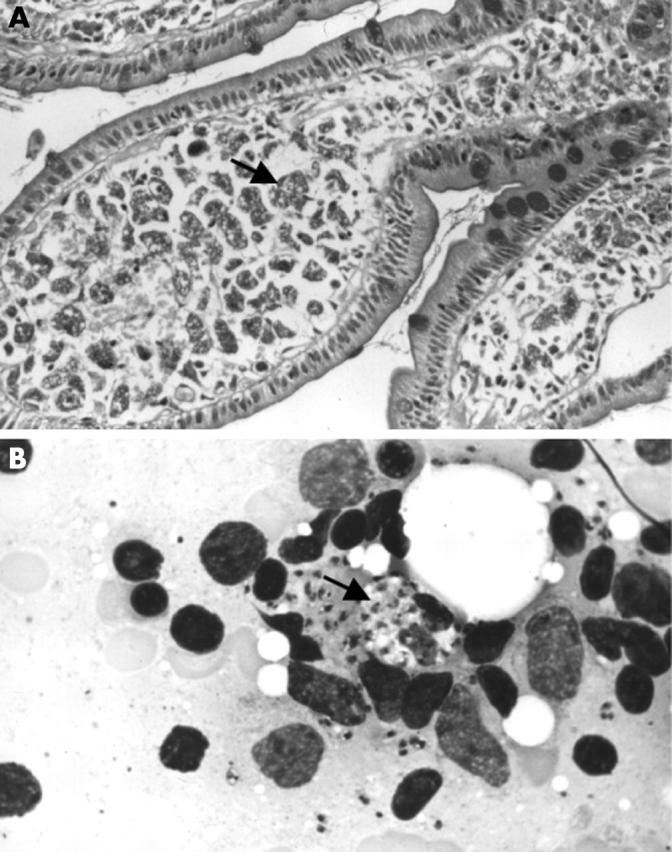

Because the abdominal ultrasonography showed an enlargement of the gastric walls, an oesophagogastroscopy was requested. Non-specific duodenitis was found and biopsies were taken. Histological examination showed abundant macrophages with intracytoplasmic leishmania amastigotes (fig 1A). The bone marrow biopsy (fig 1B) and leishmania serology (titre, 1/2560) confirmed the diagnosis. Amyloid and auramine were not detected in the bone marrow, and HIV serology was negative.

Figure 1.

(A) Duodenal biopsy showing abundant macrophages with numerous cytoplasmic leishmaniae (arrow). Periodic acid stain; original magnification, ×100. (B) Bone marrow smear showing intracellular leishmaniae (arrow). May Grünwald-Giemsa stain; original magnification, ×400.

Treatment was begun with liposomal amphotericin B (4 mg/kg/day) for five days, and subsequently once a week for five weeks. When treatment was completed, haematological indices returned to normal and the patient gained weight and began physical recovery.

DISCUSSION

Visceral leishmaniasis is an endemic parasitosis in South America, India, Northeast Africa, and the Mediterranean basin.3 Its epidemiological pattern has changed in the past 20 years; whereas before it mostly affected children, it now primarily affects adults, 65% of whom are immunodepressed (as a result of HIV infection, neoplasia, transfusions, and transplants).4 HIV coinfection is the most frequent predisposing factor. Leishmaniasis has different characteristics in patients with AIDS compared with immunocompetent patients: the location is more likely to be atypical (less often affecting the spleen and more often having a gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or laryngeal location),5 cytopenia is more frequent (50% negative serology v 20% in immunocompetent patients), recurrence is more frequent (50% after three months v 7.5% in immunocompetent patients), and the mortality rate is higher (50% after two years in HIV infected patients).6

“Despite normal mucosa at endoscopy, if gastrointestinal symptoms are present, biopsies must be taken, to rule out this rare but benign condition”

We present an example of atypical presentation of leishmaniasis in an HIV negative elderly patient—there was no fever, no hepato/splenomegaly or adenopathy, and unusual duodenal infiltration was present. Leishmania species can invade many tissues asymptomatically. However, parasitisation should be considered in those cases in which digestive tract symptoms are present. The gastrointestinal location is more frequent in HIV positive patients. In 90% of patients with AIDS the location is duodenal (45% with apparently normal mucous),7,8 and causes dysphagia, diarrhoea, or abdominal pain.9 In a series of 91 patients with coinfection of leishmania and HIV, the diagnosis was established in 15 patients only when leishmania amastigotes were found unexpectedly at atypical locations (12 of them in gastrointestinal biopsies).5 Endoscopic examination of these patients was performed because of diarrhoea, epigastralgia, or dry cough. A previous study stressed that “apparently normal mucosa” is often found at endoscopy in HIV infected patients with digestive tract symptoms; however, 45% of biopsies taken in these cases revealed leishmaniasis infection.9

The clinical manifestations may be influenced by the immunological status—leishmania amastigotes are more often found at atypical locations in severely immunocompromised hosts (< 50 CD4+ cells/mm3).

With regard to treatment, liposomal amphotericin B is as effective as meglumine antimonate (Glucantime®) and is well tolerated (less renal insufficiency) and effective in resistant cases.4,10

Take home messages.

We report an unusual duodenal presentation of leishmaniasis in a healthy elderly patient

The disease can express itself atypically in immunodepressed patients and in the elderly

Despite normal mucosa at endoscopy, if gastrointestinal symptoms are present, biopsies must be taken

In conclusion, we report an unusual duodenal presentation of leishmaniasis in an HIV negative elderly patient. Despite normal mucosa at endoscopy, if gastrointestinal symptoms are present, biopsies must be taken, to rule out this rare but benign condition.

Abbreviations

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

The patient gave her informed consent for this case report to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pineda JA, Gallardo JA, Macias J, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with visceral leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients in southern Spain. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:2419–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman JD. Human leishmaniasis: clinical, diagnostic and chemotherapeutic developments in the last 10 years. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:684–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudi J, Raez P, Horner M. Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) after a visit to the Mediterranean region. Clin Investig 1993;71:616–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reus S, Sánchez R, Portilla J, et al. Leishmaniasis visceral: estudio comparativo de pacientes con y sin infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 1999;17:515–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenthal E. HIV and Leishmania coinfection: a review of 91 cases with focus on atypical locations of Leishmania. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:1093–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pintado V, Martín-Rabadán P, Rivera ML, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-infected patients. A comparative study. Medicine 2001;80:54–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alonso MJ, Muñoz E, Picazo A, et al. Duodenal leishmaniasis diagnosed by biopsy in two HIV-positive patients. Pathol Res Pract 1997;193:43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mc Bride MO, Fisher M, Skinner CJ, et al. An unusual gastrointestinal presentation of leishmaniasis. Scand J Infect Dis 1995;27:297–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laguna F, García-Samaniego J, Soriano V, et al. Gastrointestinal leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: report of five cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 1994;19:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laguna F, Lopez-Velez R, Pulido F, et al. Treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients: a randomized trial comparing meglumine antimoniate with amphotericin B. AIDS 1999;13:1063–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]