Abstract

hDDPI (human dipeptidyl peptidase I) is a lysosomal cysteine protease involved in zymogen activation of granule-associated proteases, including granzymes A and B from cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells, cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase, and mast cell tryptase and chymase. In the present paper, we provide the first crystal structure of an hDPPI–inhibitor complex. The inhibitor Gly-Phe-CHN2 (Gly-Phe-diazomethane) was co-crystallized with hDPPI and the structure was determined at 2.0 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) resolution. The structure of the native enzyme was also determined to 2.05 Å resolution to resolve apparent discrepancies between the complex structure and the previously published structure of the native enzyme. The new structure of the native enzyme is, within the experimental error, identical with the structure of the enzyme–inhibitor complex presented here. The inhibitor interacts with three subunits of hDPPI, and is covalently bound to Cys234 at the active site. The interaction between the totally conserved Asp1 of hDPPI and the ammonium group of the inhibitor forms an essential interaction that mimics enzyme–substrate interactions. The structure of the inhibitor complex provides an explanation of the substrate specificity of hDPPI, and gives a background for the design of new inhibitors.

Keywords: cathepsin C, cysteine protease, dipeptidyl peptidase I (DPPI), Gly-Phe-diazomethane (Gly-Phe-CHN2)

Abbreviations: DPPI, dipeptidyl peptidase I; hDPPI, human DPPI

INTRODUCTION

DPPI (dipeptidyl peptidase I or cathepsin C; EC 3.4.14.1) is a lysosomal cysteine protease, which sequentially removes dipeptides from the N-termini of protein and peptide substrates. DPPI homologues have been identified by gene cloning, biochemical characterization or sequence comparison in a variety of species, including mammals (humans, other apes, cows, dogs, rabbits, rats and mice), human parasites (Plasmodium and Schistosoma), fish (rainbow trout and killifish), reptiles (frogs) and birds (chickens), suggesting an important role and a widespread presence of DPPI in Nature [1–4].

Increasing evidence of the key role of hDPPI (human DPPI) in different diseases, such as sepsis [5], arthritis [6] and other inflammatory disorders, using animal models has drawn attention to the potential of DPPI as a drug target. The availability of a mouse strain carrying a null mutation has been important to address the central role of DPPI in these diseases [5,7]. hDPPI is expressed in many tissues and is associated with protein degradation in the lysosomes. DPPI has also been assigned an important role in the activation of many granule-associated serine proteases, including cathepsin G and elastase from neutrophils, granzymes A and B from cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells, together with chymase and β-tryptase from mast cells [5,6,8–10]. These inflammatory proteases are translated as inactive zymogens. The final step in the conversion into their active forms is an hDPPI-catalysed removal of an activation dipeptide from the N-terminus. DPPI-knockout mice accumulate exclusively the inactive dipeptide-extended proforms of chymase together with granzyme A and B, providing evidence of the role of DPPI [8].

In recent years, pharmaceutical companies have targeted the inhibition of tryptase and chymase as a drug-intervention strategy. However, the active sites and catalytic activities of tryptase and chymase closely resemble a number of other proteases of the same family, including trypsin, chymotrypsin, elastase and cathepsin G. Therefore the design of inhibitors that combine selectivity, potency, bioavailability and non-toxicity for these enzymes has proved difficult. Furthermore, the large quantities of tryptase and chymase synthesized and released by mast cells poses a challenge to ensure a continuous and suitable supply of inhibitors at the sites of release. Thus hDPPI is an attractive candidate as a drug target for the treatment of the above-mentioned diseases.

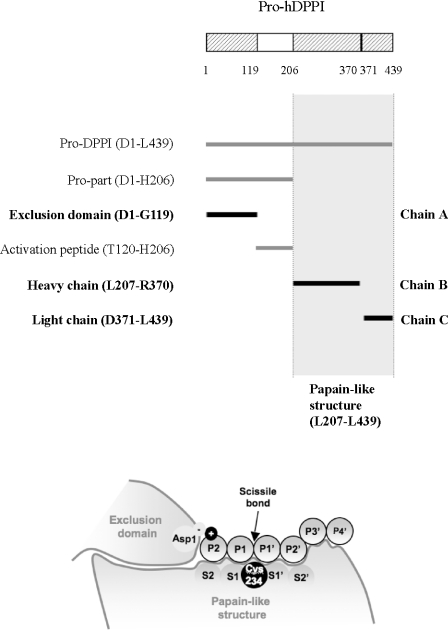

hDPPI is unique among the lysosomal cathepsins owing to an elaborate activation mechanism and its tetrameric structure [11,12]. Evidence has been reported of the likely involvement of cathepsin L and S [11] in hDPPI activation, a process initiated by the proteolytic activation of the proenzyme through the removal of a propeptide (activation peptide) of 87 residues, separating the 119-residue N-terminal exclusion domain from the papain-like domains [12] (Figure 1A). Further processing splits the papain-like structure into an N-terminal heavy chain and a C-terminal light chain by cleavage of the peptide bond between Arg370 and Asp371 [12]. The structural determinations for rat DPPI and hDPPI showed that, although the activation peptide is removed, the residual propart (the exclusion domain) remains non-covalently associated to the heavy and light chains, forming a heterotrimeric structure (Figure 1A) [12,13]. The exclusion domain is unique to DPPI and is a determinant for the exopeptidase specificity of this enzyme. The presence of the exclusion domain blocks the active-site cleft beyond the S2 site and provides the carboxy group of the Asp1 side chain as the docking residue (conserved in all known DPPI sequences) for the free amino group of the substrate required for DPPI cleavage (Figure 1B). Finally, the tetrameric structure of active DPPI displays the active site on the surface of each subunit, making it accessible to large protein substrates as well as peptides.

Figure 1. Domain structure of hDPPI and definition of substrate-binding sites.

(A) Overview of the nomenclature of the different parts of the sequence of hDPPI. One-letter amino acid codes are used. (B) Schematic drawing of the hDPPI structure in complex with a generic peptide substrate. The amino acids on the peptide bound to the enzyme are numbered P2 and P1 on the N-terminal side of the scissile bond and P1′, P2′, etc. on the C-terminal side. The corresponding substrate binding sites on the enzyme are numbered S2, S1, S1′, S2′, etc. [32,34].

The substrate requirements for effective peptidase cleavage of peptides and proteins by DPPI have been established. DPPI cleaves only substrates with a free N-terminal amino group (Figure 1B), and does not cleave substrates with P1 or P1′ proline, P1 isoleucine and P2 ornithine, lysine or arginine [14–16]. Extensive analysis of dipeptide substrates has been reported in an attempt to use this information for the design of better DPPI inhibitors [17].

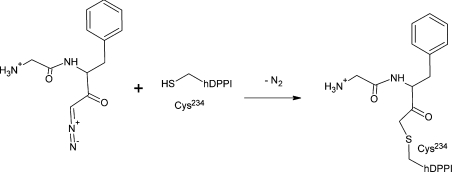

Natural DPPI inhibitors {e.g. cystatins or E-64 (trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucylamido-(4-guanidino)butane)} display broad specificity towards cysteine proteases [18]. Cystatins inhibit endopeptidases at the picomolar level and exopeptidases in the nanomolar range [12]. Other inhibitors have been discovered using different molecular diversity methods and include several types of dipeptide derivatives (e.g. diazomethyl ketones, vinyl sulfones, semicarbazides) [14,15], some of which function by reacting with the catalytic cysteine residue and thereby creating an inactive enzyme (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chemical reaction between Gly-Phe-CHN2 and hDPPI.

After the reaction, the inhibitor is covalently bound by a thioether bond to the hDPPI active-site Cys234, forming a Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI complex.

However, in spite of the availability of different DPPI inhibitors, little is known about the mechanisms involved in the inhibition and information about kinetic studies is scarce. Among the existing inhibitors, Gly-Phe-CHN2 (Gly-Phe-diazomethane) is one of the most effective compounds, with a kobs/[I] of 10−4 M−1·s−1 (Figure 2) [15,19], although its use as a therapeutic is inadequate owing to instability of the diazomethyl ketone group [15].

In order to increase our knowledge of hDPPI and to enable the rational design of novel hDPPI inhibitors, a detailed structural model of the enzyme–inhibitor complex represents an invaluable tool. Enzyme–inhibitor complexes are known for several cathepsins (for a review, see [20]), but until now only the native structures of human and rat DPPI have been determined [11,12]. Thus in the present paper, we describe the first experimental crystal structure of hDPPI in complex with an inhibitor, Gly-Phe-CHN2. Through a redetermination of the published structure of native hDPPI we also address discrepancies which were found between our hDPPI–inhibitor complex and the previously published structure of native hDPPI [12]. The refined hDPPI structure together with the structure of the inhibitor–enzyme complex represent a significant advance in the quest to develop efficient drugs for the treatment of severe human diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crystallization and data collection

Native crystals

The hDPPI protein was expressed in the insect cell/baculovirus system and purified as described previously [11]. Well-formed native crystals were obtained from hanging drops by streak-seeding drops containing 2 μl of 10 mg/ml hDPPI and 2 μl of reservoir solution. The reservoir solution consisted of 500 μl of 0.2 M potassium/sodium tartrate, 1.8 M ammonium sulfate and 0.1 M sodium citrate at pH 5.6, which is an optimization of the previously published crystallization conditions [12]. The native crystal was initially soaked in reservoir solution containing 20% glycerol and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The reflections showed a large mosaicity, and ice rings were formed. The crystal was therefore resoaked in cryoprotectant reservoir solution with a 25% glycerol concentration and flash-cooled again. This procedure was repeated four times with a clear decrease in the mosaicity of the reflections as well as a slightly higher resolution as a result. The ice rings were also eliminated by this treatment. X-ray diffraction data were recorded at 120 K on a MAR345 image plate detector mounted on a copper rotating anode generator from Rigaku (RU300).

Gly-Phe-CHN2 complex

A 1200 μl volume of hDPPI (0.8 mg/ml in 2–3 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 150 mM cysteamine, and 50% glycerol, pH 6.8–7.1) was diluted with 1200 μl of 50 mM citric acid, and 150 mM NaCl, pH 4.5. A 120 μl volume of 200 mM cysteamine and 120 μl of 0.1 M Gly-Phe-CHN2 dissolved in DMSO was added. The mixture was left for 1 h. The mixture was dialysed twice against 250 ml of buffer (20 mM Bis-Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.0) and was concentrated to 8 mg/ml. A yellow precipitate was formed which was removed by centrifugation at 4600 g for 30 min. The protein concentration in the supernatant was approx. 2 mg/ml. Crystals were grown from hanging drops using 2 μl of protein and 1 μl of reservoir solution over 500 μl of reservoir solution consisting of 23% PEG [poly-(ethylene glycol)] 4000, 0.22 M ammonium acetate and 0.1 M Mes, pH 6.0. Initially, a trigonal crystal form was obtained with space group P3121, a=84.78 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm), c=226.34 Å. These crystals diffracted to a maximum resolution of 2.7 Å with a mosaicity of 0.89° at the Beamline I711 at MAX-lab, Lund University, Lund, Sweden [21]. The long c-axis combined with the high mosaicity gave problems with low completeness due to overlaps, and therefore we attempted to optimize the cryo conditions and a new data set was collected at I711 using 33% sucrose as cryoprotectant. Remarkably, a new crystal form was obtained from a drop that also contained crystals of the trigonal crystal form. The new crystal form was identical with the one reported for the native human enzyme, orthorhombic, I222, a=87.00 Å, b=89.03 Å, c=115.57 Å. X-ray diffraction data were recorded at 100 K at Beamline I711 [21] using a CCD (charge-coupled device) detector from MAR Research. The maximum resolution was 2.0 Å, the mosaicity was 0.74° and the overall completeness of the data was 99.3%.

Refinement and structure analysis

As a starting point for the refinement of the complex and the native structures, we used a truncated form of the previously published native structure of hDPPI [12] where all regions which differed from the structure of the rat enzyme [13] were omitted. The missing parts of the protein structure and the inhibitor were built using difference electron density maps. Cycles of model rebuilding, addition of solvent molecules and N-linked glycosylation and positional and B factor refinement was carried out using refmac5 [22,23], Arp/Warp [24] and O [25]. The final models were validated using moleman2 [26] and WHAT_CHECK [27]. Crystallographic data and refinement and validation statistics are summarized in Table 1. The structures were compared using the program ESCET [28], which takes the co-ordinate precision into account when determining conformationally invariant regions. Figures 3–5 were prepared using the program PyMol (DeLano Scientific).

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Protein PDB code… | Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI (2DJF) | Native hDPPI (2DJG) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.094 | 1.5418 | |

| Space group | I222 | I222 | |

| Cell parameters (Å) | 87.00, 89.03, 115.57 | 87.48, 88.68, 114.35 | |

| Resolution range | 28.75–2.0 (2.07–2.0) | 24.04–2.05 (2.12–2.05) | |

| Number of measured reflections | 143822 | 120690 | |

| Number of unique reflections | 28953 | 25787 | |

| Completeness | 99.3 (97.5) | 96.1 (96.1) | |

| Rsym | 0.063 (0.211) | 0.051 (0.313) | |

| Number of non-H atoms used in refinement | 3071 | 3030 | |

| Protein | 2748 | 2720 | |

| Water | 246 | 211 | |

| Inhibitor | 16 | – | |

| Cruickshanks DPI* | 0.131 Å | 0.157 Å | |

| R factor | 0.161 | 0.176 | |

| Rfree | 0.200 | 0.221 | |

| Ramachandran plot outliers† | 3.9% | 3.0% | |

| Mean B value (overall, Å2) | 26.3 | 26.1 | |

| B values | |||

| Protein | 25.0 | 24.6 | |

| Water | 32.6 | 30.2 | |

| Inhibitor | 37.3 | – | |

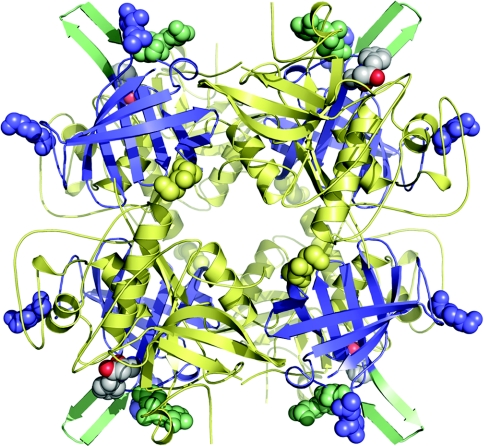

Figure 3. The biologically active tetrameric form of hDPPI in complex with the covalently bound inhibitor Gly-Phe-CHN2.

The monomers are located at the four corners of the tetramer with the exclusion domains shown in blue and the papain-like domains shown in pale yellow. The active sites can be seen on the outside of the tetramer by the location of the inhibitors which are shown with atoms as grey spheres. The structural elements close to the inhibitor-binding site, the N-linked carbohydrate at Asn5 and the β-hairpin from Lys82 to Tyr93 are shown in pale green. The other N-linked carbohydrates are shown as spheres in the same colour as the domains to which they are linked.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall structure

The crystal structure of native DPPI has been determined previously for the human [12] and rat [13] enzymes. Unlike the other papain-like lysosomal cysteine proteases, which are all monomeric [29], DPPI exists as a homotetramer, with its four independent active sites exposed to the solvent on the outside of the tetramer (Figure 3). A comparison of the Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI structure presented here (Figure 2) with the previously known uncomplexed DPPI structures from rat and human [9,10] showed a good agreement with the structure of the rat enzyme, but with some distinct differences from the previously published structure of the human enzyme [12]. The discrepancies were a frame shift in a loop from Ala21 to Ala29 in the exclusion domain, as well as a difference in the orientation of the four C-terminal residues in the papain-like structure, both of which were regions characterized by high B factors and several Ramachandran plot outliers in the previously published structure of native hDPPI [12] (see Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/401/bj4010645add.htm). In these regions, the structure of the Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI complex compare well with the structure of rat DPPI [13]. To address these apparent discrepancies, a re-determination of the native hDPPI structure was performed. After refinement of the native hDPPI structure with the new X-ray data, no significant differences between the native hDPPI structure and the Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI complex were observed (see Supplementary Figure 1, lower panel). Thus the observed differences are not caused by the presence of the inhibitor. The complex and free enzyme crystallize in the same space group with similar unit cell dimensions, which indicates very similar intermolecular interactions. It is therefore noteworthy that differences are seen in the orientation of the N-linked carbohydrate structure, which could support the theory that the carbohydrate structure at Asn5 plays a role in the determination of the substrate specificity of the enzyme [12].

The active site

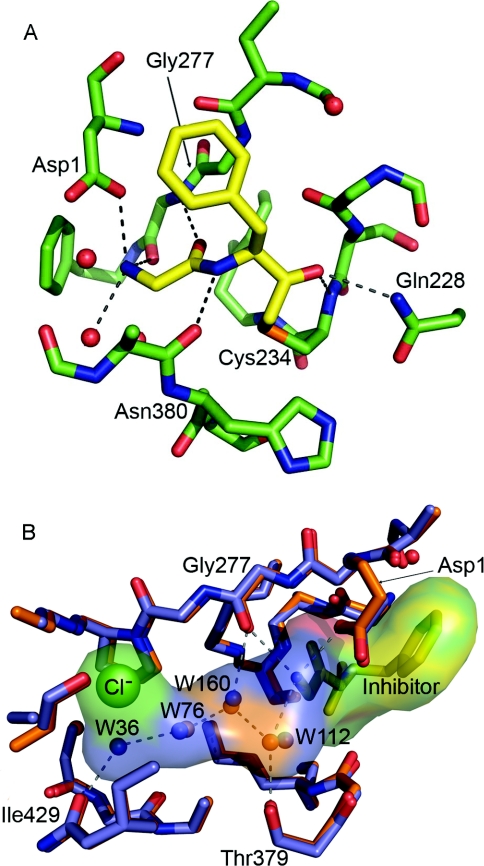

From the available DPPI sequences, several conserved amino acids could be identified. One of these is Asp1, which is a key residue that is involved in docking the substrate via interaction with the amino group. Additionally, Gln228, Ser233, Cys234 (catalytic), Gly277, Asn380 and His381 (catalytic) are conserved among all DPPI homologues. These residues are all situated in the active site and take part in the catalytic mechanism or substrate binding (Table 2, Figure 4).

Table 2. Enzyme–inhibitor interactions.

SG, sulphur at the γ position; NE2, nitrogen at the ϵ2 position; OD1, oxygen at the δ1 position.

| Inhibitor atom | Enzyme | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| CH2 C | Cys234 (chain B) SG | 1.86 |

| Phe O | Cys234 (chain B) NH | 2.97 |

| Phe O | Gln228 (chain B) NE2 | 3.03 |

| Phe NH | Asn380 (chain C) O | 3.14 |

| Gly O | Gly277 (chain B) NH | 3.02 |

| Gly NH | Gly277 (chain B) O | 3.01 |

| Gly NH | Asp1 (chain A) OD1 | 2.82 |

| Gly NH | W112 | 2.89 |

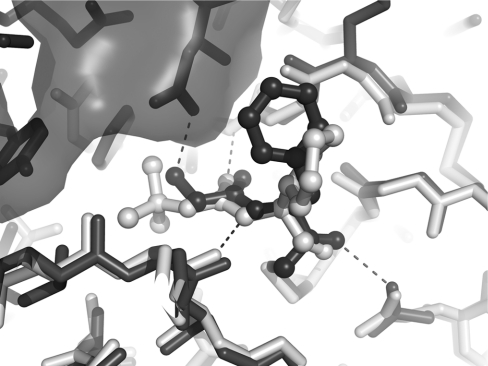

Figure 4. Active site of hDPPI.

(A) Close-up view of the active site. The carbon atoms of the inhibitor are shown in yellow. For clarity, only atoms within 5 Å of the inhibitor are included. (B) The S2 binding pocket is filled by a chain of four hydrogen-bonded water molecules (W) which are conserved in the native (blue) and the Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI (orange) structures. The inhibitor is shown as yellow sticks.

The active site of hDPPI is blocked beyond the S2 site by the exclusion domain, which determines the exo specificity of the enzyme (Figure 1B). The structural elements of the exclusion domain that are responsible for the blocking are the N-terminal residues, the N-linked carbohydrate at Asn5 and a β-hairpin (Lys82–Tyr93), which protrudes from the globular structure of the enzyme, sticking out into the solvent (Figure 3). In another lysosomal cysteine exo-peptidase, cathepsin H, access to the unprimed substrate-binding sites beyond S2 is also blocked, in this case through a covalently bound mini-chain [30]. From the comparison of hDPPI with cathepsin H, it would be expected that the C-terminal carboxy group of the exclusion domain would interact with the N-terminal ammonium group of the substrate. Instead, as predicted from the native structures of rat DPPI and hDPPI [12,13], it is the side-chain carboxy group of Asp1 which docks with the N-terminal of the substrate. This interaction is confirmed by the structure of the Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI complex (Figure 4).

Inhibitor binding to hDPPI

The inhibitor Gly-Phe-CHN2 binds to the S1 and S2 binding sites of hDPPI and is covalently linked to the active-site Cys234 (chain B) through a thioether bond (Figure 2). The inhibitor interacts with three different subunits in the hDPPI tetramer as shown in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 4. All hydrogen bond donors and acceptors from the inhibitor form hydrogen bonds with the enzyme. The strongest interaction is the salt bridge between the N-terminal ammonium group and Asp1 from the exclusion domain (chain A). The two other protons from the terminal ammonium group of the inhibitor are hydrogen-bonded to the backbone of the totally conserved Gly277 from chain B, and a water molecule (W112). This water molecule is part of a hydrogen-bonded chain of four conserved water molecules which fills out the S2 binding pocket (Figure 4B). A water-filled channel which is located behind the catalytic Cys234 may provide flexibility in the active site and a means for escape for the water molecules in the S2 binding pocket when the pocket is filled by a substrate (see Supplementary Figure 3 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/401/bj4010645add.htm). A similar water-filled cavity is also found in the other cathepsins, although in most of the other structures, it does not extend to the surface, as it does in DPPI. The carbonyl group from glycine of the inhibitor forms a hydrogen bond to the amide group of the totally conserved Gly277. The hydrogen-bonded ring system formed by the interactions between Gly277 and the N-terminal residue underlines the central role of Gly277 in substrate recognition in the S1 site. Backbone interactions are also the dominant feature of the interactions between hDPPI and the phenylalanine part of the inhibitor. Its amide group is hydrogen-bonded to the carbonyl group from the conserved Asn380 from chain C, and its carbonyl group has a similar interaction with the amide group from the catalytic Cys234 from chain B as well as an interaction with the side chain of Gln228 from chain B. Thus the interactions with the inhibitor bound to subsite S1 and S2 involve five of the seven totally conserved residues mentioned above. Of the two remaining, His381 is known to play a role in the activation of the catalytic Cys234, and Ser233 is situated next to Cys234. It is not directly involved in contacts with the inhibitor, but changes orientation of its side-chain hydroxy group upon binding of the inhibitor to form a hydrogen bond to the hydroxy group of Tyr300 and the backbone carbonyl group of Cys231. Tyr300 is furthermore hydrogen-bonded to the backbone carbonyl group of Gln228, which binds to the inhibitor, and thus a network of hydrogen bonds is formed. It should be noted that no side-chain atoms of the inhibitor participate in hydrogen bonds to the enzyme, and only two of the enzyme–inhibitor hydrogen bonds involve enzyme side-chain atoms. With the exception of the hDPPI-specific N-terminal hydrogen bond to Asp1, all of the enzyme–inhibitor hydrogen bonds are also found in other cathepsins. To compare the inhibitor–enzyme interactions in DPPI with those in other cathepsins, the structure of cathepsin K in complex with the non-covalently bound inhibitor t-butyl(1S)-1-cyclohexyl-2-oxoethylcarbamate [31] was superimposed on the hDPPI–Gly-Phe-CH2 complex. As shown in Figure 5, the two structures display very similar backbone interactions, the main differences are in the orientation of the phenyl group and the Asp1 ammonium group hydrogen bond mentioned above.

Figure 5. Superimposition of Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI (dark grey) and cathepsin K in complex on the non-covalently bound inhibitor t-butyl(1S)-1-cyclohexyl-2-oxoethylcarbamate (light grey) (PDB code 1Q6K) [31].

The inhibitors are shown in ball-and-stick representation, and the enzymes are shown as sticks. The exclusion domain of hDPPI is indicated by a transparent surface.

The backbone interactions in the S1 site gives it a character of a surface rather than a pocket, with the P1 side chain of the inhibitor pointing out towards the solvent [32]. The hydrogen bond that is formed between the backbone nitrogen of phenylalanine in the S1 site and the backbone carbonyl group of Asn380 (chain C) would not be possible with a proline residue at the P1 position, which may explain why the enzyme does not favour peptides with a proline residue in this position. The S1 site includes the non-conserved Glu275, which is located at a position where the hDPPI may interact favourably with a positively charged side chain at P1, as suggested by Turk et al. [12].

In contrast, the S2 site is a deep pocket, which can accommodate long side chains. It has been suggested that positively charged side chains will dock with the carboxy group of Asp1 and will therefore not go into the S2 pocket, which may explain why DPPI does not cleave peptides with positively charged amino acids in the N-terminus [12,13]. The S2 pocket is not occupied by the inhibitor in the Gly-Phe-CH2–hDPPI complex owing to the lack of a glycine side chain in P2. It is the inhibitor complex and the native structure filled by four water molecules which are conserved in both structures.

In the present paper, we have reported the first enzyme–inhibitor structure for DPPI, an unusual cysteine protease with a key role in several human diseases. Our study has also provided a refined structure of the native enzyme, which has clarified two poorly resolved regions in the previously published native structure [12], and may thus serve as a better template in homology modelling experiments. With the data available on the binding mode of Gly-Phe-CHN2 to hDPPI and the knowledge of the residues involved in the enzyme–inhibitor interaction, we can pursue the rational design of more effective inhibitors to provide drugs for the treatment of, for example, different inflammatory diseases in humans.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank Flemming Hansen for help with X-ray data collection, Dorthe Boelskifte and Jens-Christian Navarro Poulsen for help with crystallization, and the Danish Natural Science Research Council for financial support. The MAX-lab experiments were supported by Dansync and the ARI (Access to Research Infrastructures) programme.

References

- 1.McGuire M. J., Lipsky P. E., Thiele D. L. Cloning and characterization of the cDNA encoding mouse dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1351:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(97)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hola-Jamriska L., Tort J. F., Dalton J. P., Day S. R., Fan J., Aaskov J., Brindley P. J. Cathepsin C from Schistosoma japonicum: cDNA encoding the preproenzyme and its phylogenetic relationships. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;255:527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchinson D. W., Tunnicliffe A. The preparation and properties of immobilised dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase I (cathepsin C) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;916:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(87)90203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klemba M., Gluzman I., Goldberg D. E. A Plasmodium falciparum dipeptidyl aminopeptidase I participates in vacuolar hemoglobin degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43000–43007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallen-St Clair J., Pham C. T., Villalta S. A., Caughey G. H., Wolters P. J. Mast cell dipeptidyl peptidase I mediates survival from sepsis. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:628–634. doi: 10.1172/JCI19062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adkison A. M., Raptis S. Z., Kelley D. G., Pham C. T. Dipeptidyl peptidase I activates neutrophil-derived serine proteases and regulates the development of acute experimental arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:363–371. doi: 10.1172/JCI13462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Y., Pham C. T. Dipeptidyl peptidase I regulates the development of collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2553–2558. doi: 10.1002/art.21192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham C. T., Ley T. J. Dipeptidyl peptidase I is required for the processing and activation of granzymes A and B in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:8627–8632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolters P. J., Pham C. T., Muilenburg D. J., Ley T. J., Caughey G. H. Dipeptidyl peptidase I is essential for activation of mast cell chymases, but not tryptases, in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18551–18556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheth P. D., Pedersen J., Walls A. F., McEuen A. R. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase I in the human mast cell line HMC-1: blocked activation of tryptase, but not of the predominant chymotryptic activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66:2251–2262. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl S. W., Halkier T., Lauritzen C., Dolenc I., Pedersen J., Turk V., Turk B. Human recombinant pro-dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C) can be activated by cathepsins L and S but not by autocatalytic processing. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1671–1678. doi: 10.1021/bi001693z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turk D., Janjic V., Stern I., Podobnik M., Lamba D., Dahl S. W., Lauritzen C., Pedersen J., Turk V., Turk B. Structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C): exclusion domain added to an endopeptidase framework creates the machine for activation of granular serine proteases. EMBO J. 2001;20:6570–6582. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen J. G., Kadziola A., Lauritzen C., Pedersen J., Larsen S., Dahl S. W. Tetrameric dipeptidyl peptidase I directs substrate specificity by use of the residual pro-part domain. FEBS Lett. 2001;506:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bondebjerg J., Fuglsang H., Valeur K. R., Kaznelson D. W., Hansen J. A., Pedersen R. O., Krogh B. O., Jensen B. S., Lauritzen C., Petersen G., et al. Novel semicarbazide-derived inhibitors of human dipeptidyl peptidase I (hDPPI) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:4408–4424. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kam C. M., Gotz M. G., Koot G., McGuire M., Thiele D., Hudig D., Powers J. C. Design and evaluation of inhibitors for dipeptidyl peptidase I (Cathepsin C) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;427:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen J., Lauritzen C., Madsen M. T., Weis Dahl S. Removal of N-terminal polyhistidine tags from recombinant proteins using engineered aminopeptidases. Protein Expression Purif. 1999;15:389–400. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran T. V., Ellis K. A., Kam C. M., Hudig D., Powers J. C. Dipeptidyl peptidase I: importance of progranzyme activation sequences, other dipeptide sequences, and the N-terminal amino group of synthetic substrates for enzyme activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;403:160–170. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anastasi A., Brown M. A., Kembhavi A. A., Nicklin M. J., Sayers C. A., Sunter D. C., Barrett A. J. Cystatin, a protein inhibitor of cysteine proteinases: improved purification from egg white, characterization, and detection in chicken serum. Biochem. J. 1983;211:129–138. doi: 10.1042/bj2110129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green G. D., Shaw E. Peptidyl diazomethyl ketones are specific inactivators of thiol proteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:1923–1928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turk D., Guncar G. Lysosomal cysteine proteases (cathepsins): promising drug targets. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2003;59:203–213. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902021479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerenius Y., Ståhl K., Svensson L. A., Ursby T., Oskarsson Å., Albertsson J., Liljas A. The crystallography beamline I711 at MAX II. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2000;7:203–208. doi: 10.1107/S0909049500005331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perrakis A., Morris R., Lamzin V. S. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleywegt G. J., Jones T. A. Phi/psi-chology: Ramachandran revisited. Structure. 1996;4:1395–1400. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hooft R. W., Vriend G., Sander C., Abola E. E. Errors in protein structures. Nature. 1996;381:272. doi: 10.1038/381272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider T. R. A genetic algorithm for the identification of conformationally invariant regions in protein molecules. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:195–208. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901019291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolenc I., Turk B., Pungercic G., Ritonja A., Turk V. Oligomeric structure and substrate induced inhibition of human cathepsin C. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:21626–21631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guncar G., Podobnik M., Pungercar J., Strukelj B., Turk V., Turk D. Crystal structure of porcine cathepsin H determined at 2.1 Å resolution: location of the mini-chain C-terminal carboxyl group defines cathepsin H aminopeptidase function. Structure. 1998;6:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Catalano J. G., Deaton D. N., Furfine E. S., Hassell A. M., McFadyen R. B., Miller A. B., Miller L. R., Shewchuk L. M., Willard D. H., Jr, Wright L. L. Exploration of the P1 SAR of aldehyde cathepsin K inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turk D., Guncar G., Podobnik M., Turk B. Revised definition of substrate binding sites of papain-like cysteine proteases. Biol. Chem. 1998;379:137–147. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cruickshank D. W. Remarks about protein structure precision. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1999;55:583–601. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998012645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schechter I., Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.