Abstract

Methylation of Lys-9 of histone H3 has been associated with repression of transcription. G9a is a histone H3 Lys-9 methyltransferase localized in euchromatin and acts as a corepressor for specific transcription factors. Here we demonstrate that G9a also functions as a coactivator for nuclear receptors, cooperating synergistically with nuclear receptor coactivators GRIP1, CARM1, and p300 in transient transfection assays. This synergy depends strongly on the arginine-specific protein methyltransferase activity of CARM1 but does not absolutely require the enzymatic activity of G9a and is specific to CARM1 and G9a among various protein methyltransferases. Reduction of endogenous G9a diminished hormonal activation of an endogenous target gene by the androgen receptor, and G9a associates with regulatory regions of this same gene. G9a fused to Gal4 DNA binding domain can repress transcription in a lysine methyltransferase-dependent manner; however, the histone modifications associated with transcriptional activation can inhibit the methyltransferase activity of G9a. These findings suggest a link between histone arginine and lysine methylation and a mechanism for controlling whether G9a functions as a corepressor or coactivator.

Activation and repression of transcription involve the recruitment of many coregulator (coactivator or corepressor) proteins to the regulated gene promoter by sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factors (1, 2). These coregulator proteins contribute to transcriptional regulation by helping to remodel chromatin conformation in the promoter of the gene and by influencing the recruitment and activation of RNA polymerase II and its associated basal transcription factors. The mechanisms by which coregulators accomplish these tasks include protein-protein interactions, ATP-dependent alterations in conformations of chromatin, and catalysis of post-translational modifications of histones and other protein components of the transcription machinery.

Post-translational modifications of the N-terminal tails of histones include acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and arginine and lysine methylation. Individual histone modifications or sequential or concurrent combinations of these modifications may constitute a histone code which is then recognized by effector proteins to bring about distinct changes in chromatin structure or other aspects of transcription complex assembly and activity (3). Methylation of histones on various lysine and arginine residues has been found to play both positive and negative roles in transcriptional regulation. For example, methylation of Lys-9 of histone H3 is associated with inactive genes, while methylation of Lys-4 and Arg-17 of histone H3 has been generally associated with active or potentially active genes (4). Lysine residues can be modified to mono-, di- or trimethyl states; arginine can be modified to a monomethyl, asymmetric dimethyl, or symmetric dimethyl state. It appears that different degrees of methylation may be associated with distinct chromatin regions or transcriptional states. Trimethylation of Lys-9 of histone H3 is associated with pericentromeric heterochromatin and transcriptional repression, while dimethylation of Lys-9 appears to occur on repressed genes in euchromatin. However, these general rules which represent our current level of understanding may require some refinement if various histone modifications are indeed interpreted in combinations as part of a histone code.

Nuclear receptors (NR)1 are ligand-activated, DNA-binding transcription factors. Among the many coactivators that NRs recruit to the promoters of their target genes, one critical coactivator complex contains a member of the p160 coactivator family, which includes SRC-1, GRIP1 and AIB1. p160 coactivators bind to NRs in a ligand-dependent manner and use at least three different activation domains to recruit additional coactivators (5). The histone acetyltransferases p300 and CBP bind to AD1 of p160 coactivators, while the histone arginine methyltransferases CARM1 and PRMT1 bind to AD2 (6–9). In addition, several coactivators with no apparent enzymatic activity (e.g. CoCoA, Fli-I, and GAC63) bind to AD3 in the N-terminal region of p160 coactivators (10). Methylation of arginine residues 2, 17, and 26 of histone H3 by CARM1 and Arg-3 of histone H4 by PRMT1 occurs during hormone-dependent transcriptional activation by NRs (11, 12). Various combinations of these coactivators can cooperate synergistically to enhance transcriptional activation of NRs in transient transfection as well as chromatin-based in vitro transcription systems. For example, p300 and CBP cooperate synergistically with CARM1, and their enzymatic histone modifications are required for transcriptional activation and occur in a requisite sequence (13, 14). In contrast, histone modifications associated with repression and those associated with activation are often mutually inhibitory (15, 16).

Here we test functional relationships between coregulators which make activating and repressive histone modifications. G9a is the major euchromatic histone H3 Lys-9 methyltransferase in higher eukaryotes and is responsible for mono- and dimethylation of Lys-9 of histone H3 in euchromatin (17, 18). Previous studies found that G9a functions as a corepressor which can be targeted to specific genes by associating with transcriptional repressors and corepressors such as CDP/cut, Blimp-1/PRDI-BF1 and REST/NRSF (19–21). Here we show, surprisingly, that G9a functions as a coactivator for NRs, collaborating synergistically with CARM1 and other NR coactivators. We also tested the role of the enzymatic activities of G9a and CARM1 in their synergistic coactivator function, and we investigated potential regulatory mechanisms for the histone lysine methyltransferase activity of G9a. Our results suggest that promoter context and/or regulatory environment control whether G9a functions as a corepressor or a coactivator.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

Proteins with N-terminal hemagglutinin A or Flag epitope tags were expressed in mammalian cells and in vitro from pSG5.HA or pSG5.Flag, each of which has SV40 and T7 promoters (8, 22). Plasmids encoding the following proteins were previously constructed in pSG5.HA: GRIP1, CARM1, CARM1(VLD) (8); GRIP1ΔAD1 and GRIP1ΔAD2 (23); GRIP1 ΔN (22); PRMT1 (9); GRIP1.N (5–765), GRIP1.M (730–1121), GRIP1.C (1122–1462), CARM1(E267Q), PRMT2, PRMT3, RMT1 (13). A PCR-amplified EcoRI-XhoI insert encoding the murine long form of G9a (17) was cloned into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of pSG5.HA and pSG5.Flag. PCR-amplified EcoRI-SalI inserts of G9a residues 1–333, 72–333, 330–690, 685–1018, 936–1263 (ΔANK), 1–1088 (ΔSET), 730–1263 and 464–1263 were cloned into the EcoRI-SalI sites of the vector pM (BD Biosciences Clontech) for Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) fusions and into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of pSG5.HA or pSG5.Flag. G9a H1166K mutant was generated with the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), using pSG5.HA-G9a as the template. The pM-G9a(ΔNHLC1165–1168) plasmid encoding the mutant G9a fused to Gal4 DBD was described previously (17). This region of G9a is conserved among lysine methyltransferases and essential for methyltransferase activity (15, 17, 24). Mammalian expression vectors encoding p300 (13), human androgen receptor (AR) (pSVAR0) and human estrogen receptor (ER)α (pSG5-HE0) were described previously (8) along with luciferase reporter plasmids MMTV-Luc containing the native mouse mammary tumor virus promoter and MMTV(ERE)-Luc with an estrogen response element replacing the glucocorticoid response elements. For mammalian one-hybrid assays, GK1 and UAS-tk-LUC luciferase reporters were used. GK1 contains a minimal adenovirus E1b promoter and five tandem Gal4 response elements, and UAS-tk-LUC contains a thymidine kinase (tk) minimal promoter and five tandem Gal4 response elements.

Cell Culture and Transfections

CV-1 and Cos-7 (25) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C and 5% CO2. CV-1 cells (5 × 104/well) were seeded into 12 well dishes 18 hrs prior to transfection with a total of 1 μg/well DNA using Targefect F-1 (Targeting Systems) (8). After transfection, cells were grown in 5% charcoal-stripped FBS (Gemini Bioproducts) for 48 hrs in the absence or presence of 20 nM dihydrotestosterone for AR or 20 nM estradiol for ER. Cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity using a luciferase assay kit (Promega) as described previously (8). Results shown are the mean and deviation from the mean for two transfected wells. The results are representative of at least four independent experiments. For coimmunoprecipitation assays and protein expression assays Cos-7 cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/10 cm dish 1 day prior to transfection with a total of 2.5 or 5 μg expression vector using Targefect F-2 (Targeting Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein-Protein Interactions

GST fusion proteins were produced in E. coli strain BL21 by standard methods using glutathione agarose (Sigma) affinity chromatography. GRIP1 fragments, GRIP1.N, GRIP1.M, GRIP1.C were cloned into the vector pGEX4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences) for expression. 35S-labeled G9a was synthesized in vitro by transcription and translation using the TNT-T7 coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). GST pull-down assays were performed as described previously (9). Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed as described previously (13) using anti-Flag antibody (M2, Sigma), anti-HA antibody (3F10, Roche) or normal mouse or normal rat IgG for immunoprecipitations followed by either anti-HA antibody (3F10, Roche) or by anti-Flag antibody for immunoblotting. Further antibodies used for immunoblotting were anti-G9a (Sigma), anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-PSA (DAKO Corp.).

Small Interfering RNA Transfection and Quantitative RT-PCR

LNCaP cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped FBS for 2 days in 6 well plates. Cells were transfected with 90 nM siRNA using siLentFect (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Starting 48 hrs after transfection, cells were treated with 100 nM DHT for 20 hrs. Total cellular RNA was prepared using Trizol (Invitrogen) and a two-step reverse transcription-PCR method was used to quantify specific mRNAs. Total RNA (400 ng) was subjected to reverse transcription (iScript cDNA synthesis kit, BioRad) followed by quantitative PCR with Brilliant SYBR Green PCR master mix and the Mx3000P system (Stratagene). The primer sequences for qPCR are as follows: hG9a, 5′-GAGGTGTACTGCATAGATGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGACGGCTCTGCTCCAGGGC-3′ (reverse); hβ-actin, 5′-ACCCCATCGAGCACGGCATCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCACCGGAGTCCATCACGATG-3′ (reverse); hPSA, 5′-TCACAGCTACCCACTGCATCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGTCGTGGCTGGAGTCATC-3′ (reverse). siRNA sequences are as follows (Dharmacon): siG9a, 5′-UGAGAGAGGAUGAUUCUUAUU-3′ (sense) and 5′-UAAGAAUCAUCCUCUCUCAUU-3′ (antisense); siControl (negative control siRNA having no perfect matches to known human or mouse genes), 5′-UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUACUU-3′ (sense) and 5′-GUAUCUCUUCAUAGCCUUAUU-3′ (antisense).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

ChIP assays were performed essentially as described (26, 27) using LNCaP cells cultured as above in 150 mm dishes prior to treatment with 100 nM DHT for from 0 to 60 min. Cross-linked and sheared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-AR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-G9a (Sigma) or normal rabbit IgG. Quantitative PCR amplifications were performed as described above using the following primers representing different portions of the human PSA gene: enhancer forward, 5′-GGGGTTTGTGCCACTGGTGAG-3′ reverse, 5′-GGGAGGCAATTCTCCATGGTT-3′ enhancer-promoter forward, 5′-TAGAAGACGTGGAAGTAGCTG-3′ reverse, 5′-AACCTCATGGATCCGGTGTCC-3′ promoter forward, 5′-TCTAGTTTCTGGTCTCAGAG-3′ reverse, 5′-TTGCTGTTCTGCAATTACTAG-3′ intron 1 forward, 5′-CCAAGGACCTCTCTCAATGC-3′ reverse, 5′-AGGGAATGAGGAGTTCTCAG-3′ exon 3 forward, 5′-CACACCCGCTCTACGATATGAG-3′ reverse, 5′-GAGCTCGGCAGGCTCTGACAG-3′ 3′ UTR forward, 5′-TACTGGCCATGCCTGGAGAC-3′ reverse, 5′-TGGCTCACAGCCTTCTCTAG-3.

Methyltransferase Assays

Bacterially produced GST fusion proteins of full-length CARM1 or G9a residues 730–1263 (mouse long form) were incubated with histone H3 tail peptides (amino acids 1–21, Upstate), containing various post-translational modifications, in the presence of 3H-labeled S-adenosyl-l-methionine. Radioactive methylated products were analyzed by standard denaturing SDS gel electrophoresis using 15% (acrylamide/Bis, 29:1) gels and autofluorography.

RESULTS

We first tested whether the histone H3 Lys-9 methyltransferase G9a can enhance or inhibit transcriptional activation of transiently transfected reporter plasmids by steroid hormone receptors in CV-1 cells. We used previously established conditions that allow synergistic effects of multiple coactivators to be observed (13). Reporter gene expression mediated by hormone-activated AR and ERα (Fig. 1A and B) was enhanced by GRIP1 and further enhanced by CARM1. G9a alone exhibited little coactivator activity, but it cooperated strongly with GRIP1; furthermore, the combination of G9a, GRIP1, and CARM1 was highly synergistic, producing an activity level up to 20-fold higher than that achieved with GRIP1 and CARM1. The synergy was entirely dependent on the steroid hormone (Fig. 1A) as well as GRIP1 (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained with glucocorticoid receptor (Sup. Fig. S1) and thyroid hormone receptor β1 (data not shown). G9a cooperated synergistically with selective combinations of coactivators. In the presence of GRIP1, G9a was highly synergistic with CARM1, but not with p300; however, addition of G9a to the combination of GRIP1, CARM1, and p300 produced a dramatic synergy (Fig. 1C). Thus, while G9a cooperated with GRIP1, CARM1, and p300, its coactivator function was more highly dependent on GRIP1 and CARM1.

Fig. 1.

G9a is a coactivator for AR and ERα. CV-1 cells were transfected with MMTV-LUC (A) or MMTV(ERE)-LUC (B and C) reporter plasmids (125 ng) and expression vectors encoding AR (10 ng), ERα (1 ng), GRIP1 (50 ng), CARM1 (200 ng), G9a ( 50, 100, 200 (+) and 400 ng) and p300 (200 ng) as indicated. Cells were grown with or without 20 nM DHT or 20 nM E2 as indicated and assayed for luciferase activity.

Sup. Fig. S1.

G9a is a coactivator for GR. CV-1 cells were transfected with MMTV-LUC reporter plasmid (125 ng) and expression vectors encoding GR (10 ng), GRIP1 (50 ng), CARM1 (200 ng), and G9a (50, 100, 200 (+) and 400 ng). Cells were grown with or without 20 nM dexamethasone as indicated and assayed for luciferase activity.

To test the requirement for CARM1’s enzymatic activity in its synergistic action with G9a, we used two mutants of CARM1 that lack enzymatic activity in vitro: mutation of VLD (amino acids 189–191) to AAA in the SAM binding domain and the E267Q mutation in the arginine binding pocket. Both mutants maintain the ability to bind to AD2 of GRIP1 and are expressed at wild type levels (8, 13). The synergistic enhancement of AR function by GRIP1, wild type CARM1, and G9a was completely lost when either of the two CARM1 mutants was substituted for wild type CARM1 (Fig. 2A). The activity observed with the CARM1 (E267Q) mutation was equivalent to that observed with no CARM1, while the CARM1 (VLD) mutant displayed a dominant negative behavior. Thus, the enzymatic activity of CARM1 is required for the coactivator synergy between G9a and CARM1.

Fig. 2.

The methyltransferase activity of CARM1 but not that of G9a is required for coactivator synergy. (A and B) CV-1 cells were transfected with MMTV-LUC reporter plasmid (125 ng) and with expression vectors encoding AR (10 ng), GRIP1 (50 ng), CARM1 wild type or mutant (200 ng), and G9a wild type or mutant (50, 100, 200 and 400 ng). Cells were treated with 20 nM DHT prior to luciferase assays. The schematic diagram shows full-length G9a and the residue numbering of fragments used in this study. E, polyglutamate; Cys, cysteine rich region; ANK, six ankyrin repeats; Pre- and Post-SET domains; SET, H3 Lys-9 methyltransferase domain; asterisk, location of H1166K mutation in the SET domain. (C) Cos-7 cells were transfected with the G9a expression vectors used in panel B above. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed for G9a expression by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. (D) CV-1 cells were transfected with GK1 reporter plasmid (250 ng) and expression vectors encoding Gal4 DBD (vector) or Gal4 DBD fused to various G9a fragments (250 ng each). After 48 hrs cell extracts were analyzed for luciferase activity. Inset graph shows the same results on a different scale without assay 3.

To test whether the histone lysine methyltransferase activity of G9a is required for its synergistic cooperation with CARM1, we used mutants that lack the enzymatic activity in vitro: mutation H1166K in the catalytic site of the SET domain or deletion of the entire SET domain. The synergistic coactivator function observed with GRIP1, CARM1, and wild type G9a was reduced but not eliminated when G9a (H1166K) or G9a (ΔSET) was substituted for wild type G9a (Fig. 2B). In contrast, a G9a fragment consisting of the SET domain alone and missing the ankyrin repeats (ΔANK) was inactive as a coactivator. The G9a (H1166K) and G9a (ΔSET) mutants were less efficient than wild type G9a when lower levels of the plasmids were transfected, but were almost equivalent to wild type G9a when higher levels of plasmid were transfected. While the G9a mutants are expressed at approximately wild type levels when over-expressed in Cos-7 cells (Fig. 2C), we cannot rule out the possibility that modest reductions in their expression levels may account for the lower activities observed in Fig. 2B. Thus, the methyltransferase activity of G9a is not absolutely required for, but may contribute to, the synergistic coactivator function of G9a with CARM1.

We next tested whether any part of G9a, when brought to a promoter, could activate transcription. Fig. 2D shows the results of cotransfecting fragments of G9a fused to the Gal4 DBD with a Gal4-responsive reporter gene. The fragment containing G9a residues 72–333 contains an autonomous activation domain while no other isolated fragment of the protein has such an activity. Interestingly, the first 71 residues of the protein appear to have a negative effect on this autonomous activity (compare assays 2 and 3, Fig. 2D).

To further define the specificity of the synergy between CARM1 and G9a, we tested various combinations of arginine and lysine methyltransferases in the transient transfection assays. The coactivator synergy between G9a and CARM1 was not observed when mammalian arginine methyltransferase PRMT1, PRMT2, or PRMT3 or yeast RMT1 was substituted for CARM1 (Fig. 3A). Each of these arginine methyltransferases exhibited similar coactivator activity when assayed with GRIP1 (13). PRMT1 and PRMT3 methylate histone H4 on Arg-3, among other substrates (4). Similarly, the mammalian histone H4 Lys-20 methyltransferase PR-SET7 could not be substituted for G9a (Fig. 3B) although both proteins can be expressed at high levels (Fig. 3C). Thus, among various histone methyltransferases, CARM1 and G9a have specific characteristics that allow them to function with each other as synergistic coactivators.

Fig. 3.

Specificity of coactivator synergy among protein arginine and lysine methyltransferases. (A and B) CV-1 cells were transfected with MMTV-LUC reporter plasmid (125 ng) and with plasmids encoding AR (10 ng); GRIP1 (50 ng); CARM1, PRMT1, PRMT2, PRMT3, or RMT1 (200 ng); and HA-tagged G9a or PR-SET7 (50, 100, 200, and 400 ng). Cells were treated with 20 nM DHT and luciferase assays were performed. (C) Cos-7 cells were transfected with the G9a and PR-SET7 vectors used in panel B or mock transfected. Whole-cell extracts were analyzed for protein expression by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody.

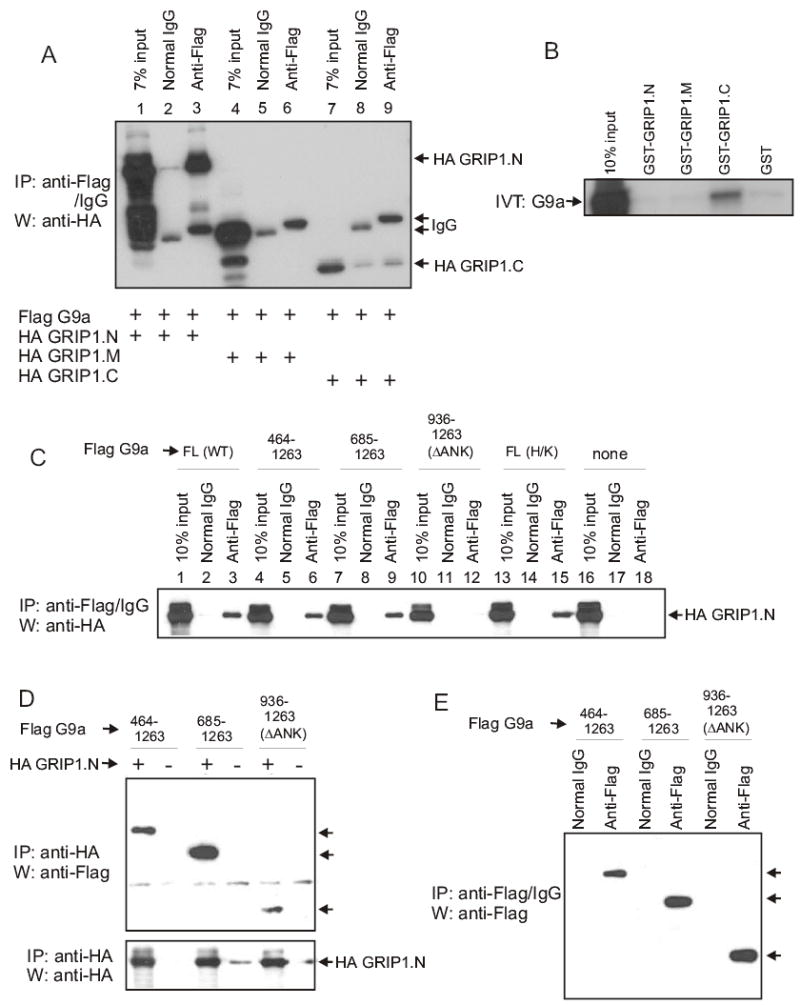

Because GRIP1 was important for the synergy between CARM1 and G9a, we explored physical interactions between G9a and specific GRIP1 domains. In co-immunoprecipitation experiments, G9a bound strongly to GRIP1.N (5–765) but not to the middle or C-terminal regions of GRIP1 (Fig. 4A). The interaction of G9a with GRIP1.N was apparently indirect or required post-translational modification, because no binding was observed between G9a translated in vitro and bacterially produced GST-GRIP1.N (Fig. 4B). However, G9a did bind weakly to the GRIP1 C-terminal region in vitro. The region of G9a involved in its association with GRIP1.N was further mapped using N-terminal truncations (Fig. 4C–E). While truncated G9a proteins containing the ankyrin repeats, as well as the full-length G9a protein bound to GRIP1.N equally well, the SET domain alone bound only very weakly (Figs. 4C and D) although it was expressed in equal or greater amounts as compared to the larger proteins (Fig. 4E). In addition, point mutation of the SET domain in full-length G9a to a catalytically inactive form did not inhibit association with GRIP1.N (Fig. 4C). The binding of G9a to GRIP1 (whether direct or indirect) suggests a possible mechanism for recruitment of G9a to the promoter by NRs.

Fig. 4.

Binding of G9a to GRIP1. (A) Cos-7 cells were transfected with expression vectors (2.5 μg each) for Flag-G9a and one of the following: HA-GRIP1.N, HA-GRIP1.M or HA-GRIP1.C. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Flag antibody or normal IgG and then immunoblotted (W) with anti-HA antibody. The positions of coimmunoprecipitated GRIP1.N and GRIP1.C and of immunoglobulin heavy chains (IgG) are indicated. (B) 35S-labelled G9a was incubated with GST, GST-GRIP1.N, GST-GRIP1.M or GST-GRIP1.C immobilized on glutathione-agarose beads. Bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (C) Cos-7 cells were transfected as in panel A with Flag-G9a full-length (FL), either wild type (WT) or H1166K (H/K) mutant, N-terminal truncations (residues 464–1263, 685–1263 or 936–1263/ΔANK) or no G9a (none) and with HA-GRIP1.N. Extracts were processed as in panel A; coimmunoprecipitated GRIP1.N is indicated. (D) Cos-7 cells were transfected with G9a N-terminal truncations and either with or without HA-GRIP1.N. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting as indicated. (E) Extracts from Cos-7 cells with transfected HA-GRIP1.N in panel D were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting as indicated. Arrows in panels D and E indicate positions of G9a N-terminally truncated proteins.

In transient transfection assays GRIP1 mutants lacking the N-terminal AD3 domain (which associates with G9a and binds several other coactivators), the C-terminal AD2 domain (which binds CARM1), or the AD1 domain (which binds p300/CBP) all had substantially reduced ability to support the G9a-CARM1 coactivator synergy (Sup. Fig. S2). The mutant GRIP1 proteins are all expressed at similar levels (13, 23, 27). These results reinforce the key role of GRIP1 as a primary coactivator that binds directly to NRs and serves as a scaffold for recruiting p300, CARM1, G9a, and other secondary coactivators to contribute to transcriptional activation.

Sup. Fig. S2.

GRIP1 functional domains involved in CARM1 and G9a synergy. CV-1 cells were transfected with MMTV-LUC reporter plasmid (125 ng) and expression vectors encoding AR (10 ng), wild-type or mutant GRIP1 (50 ng), CARM1 (200 ng), and G9a (50, 100, 200, and 400 ng). Transfected cells were grown in medium with 20 nM DHT for 48 hrs before assay for luciferase activity.

We examined the effect of reducing endogenous G9a on androgen-dependent activation of the prostate specific antigen (PSA) gene in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. In a typical experiment siRNA against G9a lowered endogenous levels of G9a mRNA by about 75%, compared with cells receiving no siRNA or a control siRNA (Fig. 5A, assays 2–4). Addition of the AR agonist DHT caused strong induction of PSA mRNA levels (Fig 5B, assays 1–2). The siRNA against G9a lowered the hormone-induced level of PSA mRNA by about 50%, while control siRNA had no effect (assays 3–4). The G9a and PSA mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels, thus demonstrating that the effects of the G9a-directed siRNA were gene-specific. The siRNA against G9a also compromised the hormonal induction of PSA protein (Fig. 5C). Thus, although many different coactivators are involved in mediating transcriptional activation by NRs, endogenous G9a is necessary for efficient induction of the endogenous PSA gene in response to hormone. Similar results were obtained with induction of the endogenous pS2 gene by estradiol in MCF7 breast cancer cells (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

G9a is necessary for efficient transcriptional activation by AR. siRNA against G9a or control siRNA was transfected into LNCaP cells. After growth with or without DHT, cDNA was synthesized from total RNA and analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR. The level of G9a mRNA (A) or PSA mRNA (B) was normalized to that of β-actin; all ratios are expressed relative to the DHT-only samples (assay 2). Compared with DHT treatment alone, siRNA against G9a reduced G9a mRNA by 75% (p<0.0001 and 95% confidence interval of ±3%) and reduced PSA mRNA by 48% (p<0.0001 and 95% confidence interval of ±9%). Statistical significance was calculated using a paired 2-tailed t-test on eight independent experiments. (C) LNCaP cells were treated with siRNA and DHT as above, and cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblot, using antibodies against the indicated proteins.

G9a has been associated with transcriptional repression both through its ability to associate with repressive transcription factors (19–21) and through its ability to methylate H3 Lys-9 (17). By fusing various fragments of G9a to Gal4 DBD, we confirmed that the C-terminal SET domain, which contains the methyltransferase activity, contains the transcriptional repression activity of G9a (Fig. 6A). Mutations in the SET domain (ΔNHLC or H1166K) which eliminate the methyltransferase activity also eliminated transcriptional repression by full length G9a and its C-terminal fragments, showing that the methyltransferase activity is required for repression by G9a. The SET domain mutant G9a proteins are expressed at levels comparable to the corresponding wild type proteins. ((17) and Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

The SET methyltransferase activity of G9a can repress transcription but can also be inhibited by histone modifications associated with active transcription. (A) CV-1 cells were transfected with UAS-tk-LUC reporter plasmid (500 ng) and expression vectors (250 ng) encoding Gal4 DBD (vector) or Gal4 DBD fused to either full-length wild-type (WT) or active site deleted (ΔNHLC), or fragments of G9a with wild type or H1166K (H/K) mutant sequence. (B) Cos-7 cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of the wild type or H/K mutant G9a-Gal4 DBD fusion expression vectors used in panel A. Whole cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-G9a antibody. The positions of the fusion proteins are indicated; arrow indicates position of endogenous G9a. (C) Histone H3 peptides (residues 1–21) were methylated with GST-G9a (730–1263) or GST-CARM1. Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Equal amounts of each peptide (determined by staining) were loaded on the gel (data not shown).

We have thus demonstrated that G9a can function as a coactivator or corepressor; this presumably depends on the context of transcription factors and other coregulators at the promoter. What specific factors direct G9a to function as a coactivator rather than a corepressor? Elimination of its methyltransferase activity or the presence of a poor substrate should prevent G9a from functioning as a corepressor and could therefore possibly allow G9a to function as a coactivator. We tested whether histone H3 modifications associated with active genes could restrict the ability of G9a to methylate Lys-9. Using histone H3 peptides (amino acids 1–21) as substrates for methylation by G9a in the presence of [3H]SAM, we found that acetylation of Lys-9 and phosphorylation of Ser-10 each caused complete inhibition of G9a methyltransferase activity, while Lys-14 acetylation had no effect (Fig. 6C). In contrast, CARM1 was able to methylate all of these peptides, except for the Ser-10 phosphorylated peptide. Therefore, a combination of Lys-9 acetylation and Ser-10 phosphorylation (marks associated with transcriptional activation) would presumably cause a dramatic restriction of G9a’s ability to methylate Lys-9 and thus could help direct G9a to function as a coactivator rather than a corepressor.

Finally, since G9a can function as a coactivator we sought to verify that G9a could be found associated with transcriptionally active genes. To determine whether G9a is recruited to NR-responsive genes we performed ChIP assays. Using the androgen-responsive PSA gene we found that G9a is associated most strongly with the upstream enhancer region but, notably, also with other regions including the transcribed portion of the gene (Fig. 7). While the association of the androgen receptor with the enhancer region is highly dependent on hormone, the association of G9a appears largely constitutive to the regions examined. Nevertheless, these results demonstrate that G9a is found associated with both the inactive and transcriptionally activated states of the PSA gene. These results are consistent with a role for G9a in transcriptional regulation.

Fig. 7.

ChIP assay for the androgen receptor and G9a at the PSA gene. (Top) schematic diagram of the PSA gene showing the positions of major elements including AREs I, II and III (black boxes). E-P, intervening region between the enhancer and promoter regions. Arrow indicates the transcription start site and direction. Thick lines below the gene diagram indicate positions of PCR amplified fragments. (Bottom) real-time PCR analysis using primer pairs as described in Experimental Procedures. The results are shown as a percentage of the input chromatin and are the mean and standard deviation of triplicate reactions. The immunoprecipitating antibody (antiAR, anti-G9a or IgG) is indicated at left.

DISCUSSION

Di- and trimethylation of Lys-9 of histone H3 is generally low in active genes and higher in inactive genes (28, 29). However, a recent study suggests that the pattern of Lys-9 methylation may be more complex and have different roles in the promoters versus the transcribed regions of genes. Di- and trimethylation of histone H3 Lys-9 was found, along with the methyl(Lys-9)-histone H3 binding protein HP1γ, as a common feature in the transcribed regions of active genes (30). Moreover, their presence was dependent on active elongation by RNA polymerase II. Although further studies are needed (in light of these new findings) to examine H3 Lys-9 methylation patterns in more detail, this result suggests a role for histone H3 Lys-9 methylation and HP1 proteins in the transcription of active genes. The enzyme responsible for these modifications has not yet been identified, but our results strongly suggest G9a as a prime candidate for this function.

The extensive mechanisms for modulating chromatin structure and for recruiting and activating RNA polymerase II involve many different coregulators and complexes of coregulators, each of which appears to play a specific role in transcriptional activation (1, 2). We have shown that G9a, a protein thought to be central to a large number of gene repression events in euchromatin, is also involved in transcriptional activation by several members of the large family of nuclear receptors (Figs. 1 & 5 and data not shown). G9a acts in synergy with the p160 coactivator GRIP1, the protein arginine methyltransferase CARM1, and the histone acetlytransferase p300 (Figs. 1–3). The repressive activity of G9a depends on its lysine methyltransferase activity; however, G9a methyltransferase activity is inhibited by histone modifications associated with transcriptional activation (Fig. 6). We propose that this restriction of G9a methyltransferase activity could allow G9a to operate as a coactivator.

In order to function as a coactivator, G9a must have a mechanism for associating with the gene that will be activated and a mechanism for transmitting an activating signal to the chromatin or transcription machinery. Several characteristics of G9a suggest potential mechanisms of recruitment to genes targeted for activation. First, G9a is associated with euchromatin, placing it in the proper chromatin domain. Second, G9a can bind to the N-terminal tail of histone H3 (our unpublished results). Third, G9a can associate with GRIP1 (Fig. 4). In fact, the coactivator function of G9a is highly dependent on GRIP1 (Fig. 1) and various functional domains of GRIP1. Deletion of any of the three activation domains of GRIP1 (N-terminal AD3 or C-terminal AD1 or AD2) compromised the ability of G9a to function as a coactivator (Sup. Fig. S2). These results reflect the role of GRIP1 as a NR-binding coactivator that functions as a scaffold to recruit p300/CBP (through AD1), CARM1 (through AD2), and G9a as well as other coactivators that bind to the N-terminal AD3 of GRIP1.

Our results also suggest possible mechanisms by which G9a may transmit the activating signal downstream toward the transcription machinery. The N-terminal region of G9a contains an autonomous activation activity (Fig. 2D). The centrally located ankyrin repeats, which are known to function in protein-protein interaction in other proteins, associate with GRIP.N but could also make contact with other upstream or downstream components of the coactivator signaling pathway. Although the C-terminal SET domain was not absolutely required for the coactivator function of G9a, G9a mutants with methyltransferase-inactivating deletions or point mutations in this domain appeared to have reduced activity at lower levels of G9a expression, suggesting that G9a methyltransferase activity may contribute to coactivator function in some way (Fig. 2B).

In addition to G9a, at least two other lysine methyltransferases have been shown to work as coactivators for nuclear receptors. Riz1, which can dimethylate Lys-9 of histone H3, acts as a coactivator for the estrogen and progesterone receptors but not for several other NRs (31). NSD1 which can methylate both H3 Lys-36 and H4 Lys-20 in vitro (32), acts as a coactivator and corepressor for NRs (33). These methylation marks have been associated with transcriptional elongation and gene repression, respectively.

What factors regulate whether G9a acts as coactivator or corepressor? We propose that promoter context determines whether G9a functions as a corepressor or coactivator. G9a is recruited as a corepressor by several sequence specific DNA binding repressor proteins. Similarly, protein-protein interactions between G9a and coactivators such as GRIP1 (Fig. 4) could be a factor that switches G9a from corepressor to coactivator. The functional switch then could be simply mediated by recruitment to either the potentially activated or repressed promoter. Alternatively, since our ChIP data indicate that G9a is present at enhancer and promoter regions in the absence or presence of gene activation, absolute recruitment may not be a functional switch. Rather, the nature of the recruiting proteins, such as histone H3 vs. GRIP1, may convert G9a from corepressor to coactivator. Dimethylation of H3 Lys-9 has been associated with repression of transcription in euchromatin, and the methyltransferase activity of G9a, located in the SET domain, is required for its corepressor function (19–21). Our results also indicate that tethering of G9a to a promoter can repress transcription and that its methyltransferase activity is necessary for this repression (Fig. 6A). Therefore, another possible contributing mechanism for switching G9a from corepressor to coactivator would be to inhibit its methyltransferase activity, at least when it is recruited to an active promoter region. Acetylation and methylation of Lys-9 are obviously mutually inhibitory, as confirmed by our results (Fig. 6C). Methylation of Lys-9 of histone H3 has previously been shown to interact with other histone modifications. Lys-9 methylation is mutually inhibitory with Lys-4 methylation (16), and these marks are inversely correlated with each other in inactive and active chromatin (28, 29). In addition, Lys-9 methylation by Suv39h1 inhibits Ser-10 phosphorylation (15), and our results show that Ser-10 phosphorylation also inhibits G9a-mediated methylation (Fig. 6C). Therefore, histone H3 tails containing several histone marks associated with active transcription serve as poor substrates for G9a.

The cooperative coactivator function between CARM1 and G9a is quite specific for CARM1 in that no other PRMT tested was able to cooperate with G9a (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the methyltransferase activity of CARM1 was essential for the synergistic cooperation between CARM1 and G9a (Fig. 2A). These results suggest a specific role for H3 Arg-17 methylation (the major histone target of CARM1) in G9a coactivator function. We have examined both the interaction of G9a and the methyltransferase activity of G9a with Arg-17 methylated H3 peptides. Thus far we have been unable to show a significant difference between unmodified peptides and Arg-17 methylated peptides in these assays (data not shown). However we cannot rule out direct effects of Arg-17 methylation that, when combined with one or more other activating marks such as Lys-9 acetylation, Ser-10 phosphorylation or Lys-4 methylation, might have significant effects on G9a recruitment and/or methyltransferase activity. While transcription activating histone modifications in the promoter region may prevent Lys-9 methylation in the promoter, they apparently do not inhibit Lys-9 di- and trimethylation in the transcribed region of active genes, since levels of Lys-9 methylation were recently reported to be higher in the bodies of active versus inactive genes (30).

In summary G9a is capable of functioning either as a coactivator or as a corepressor depending on the promoter context to which it is recruited. Our results suggest that some level of regulation of the methyltransferase activity of G9a is necessary for coactivator activity and that G9a reads and responds to postranslational modifications of histone H3, consistent with the existence of a histone code.

Footnotes

We thank Dr. Yoichi Shinkai (Kyoto University, Kyoto) for mG9a constructs; Dr. Judd Rice and Jennifer Sims (University of Southern California) for the PR-SET7 expression plasmid and help with siRNA experiments. We thank Dr. Li Jia and Dr. Gerhard A. Coetzee (University of Southern California) for help with real time PCR and Dan Gerke, Kelly Chang, Irina Ianculescu and Dan Purcell (University of Southern California) for technical assistance. This work was supported by an award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (DK55274) to M.R.S. D.Y.L was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from NIH training grant DE07211.

The abbreviations used are: NR, nuclear receptor; GRIP1, glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1; SRC-1, steroid receptor coactivator 1; AIB1, amplified in breast cancer 1; CARM1, coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1; PRMT, protein arginine methyltransferase; CBP, CREB-binding protein; AD, activation domain; AR, androgen receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; SET, Su(var), Enhancer of Zeste, Trithorax; ANK, ankyrin repeats; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; HA, hemagglutinin A; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; E2, estradiol; SAM, S-adenosyl-l-methionine

References

- 1.McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Cell. 2002;108:465–474. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Genes Dev. 2000;14:121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strahl BD, Allis CD. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee DY, Teyssier C, Strahl BD, Stallcup MR. EndocrRev. 2005;26:147–170. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stallcup MR, Kim JH, Teyssier C, Lee YH, Ma H, Chen D. JSteroid BiochemMolBiol. 2003;85:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voegel JJ, Heine MJS, Tini M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. EMBO J. 1998;17:507–519. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Lin RJ, Schiltz RL, Chakravarti D, Nash A, Nagy L, Privalsky ML, Nakatani Y, Evans RM. Cell. 1997;90:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, Koh SS, Huang SM, Schurter BT, Aswad DW, Stallcup MR. Science. 1999;284:2174–2177. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh SS, Chen D, Lee YH, Stallcup MR. JBiolChem. 2001;276:1089–1098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YH, Kim JH, Stallcup MR. MolCell Biol. 2005;25:5965–5972. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.5965-5972.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma H, Baumann CT, Li H, Strahl BD, Rice R, Jelinek MA, Aswad DW, Allis CD, Hager GL, Stallcup MR. CurrBiol. 2001;11:1981–1985. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strahl BD, Briggs SD, Brame CJ, Caldwell JA, Koh SS, Ma H, Cook RG, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Stallcup MR, Allis CD. CurrBiol. 2001;11:996–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YH, Koh SS, Zhang X, Cheng X, Stallcup MR. MolCellBiol. 2002;22:3621–3632. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3621-3632.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An W, Kim J, Roeder RG. Cell. 2004;117:735–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rea S, Eisenhaber F, O'Carroll D, Strahl BD, Sun ZW, Schmid M, Opravil S, Mechtler K, Ponting CP, Allis CD, Jenuwein T. Nature. 2000;406:593–599. doi: 10.1038/35020506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishioka K, Chuikov S, Sarma K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Allis CD, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Genes Dev. 2002;16:479–489. doi: 10.1101/gad.967202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tachibana M, Sugimoto K, Nozaki M, Ueda J, Ohta T, Ohki M, Fukuda M, Takeda N, Niida H, Kato H, Shinkai Y. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1779–1791. doi: 10.1101/gad.989402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice JC, Briggs SD, Ueberheide B, Barber CM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Shinkai Y, Allis CD. MolCell. 2003;12:1591–1598. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishio H, Walsh MJ. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 2004;101:11257–11262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401343101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gyory I, Wu J, Fejer G, Seto E, Wright KL. NatImmunol. 2004;5:299–308. doi: 10.1038/ni1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roopra A, Qazi R, Schoenike B, Daley TJ, Morrison JF. MolCell. 2004;14:727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YH, Campbell HD, Stallcup MR. MolCell Biol. 2004;24:2103–2117. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.2103-2117.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma H, Hong H, Huang SM, Irvine RA, Webb P, Kushner PJ, Coetzee GA, Stallcup MR. MolCellBiol. 1999;19:6164–6173. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart MD, Li J, Wong J. MolCell Biol. 2005;25:2525–2538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2525-2538.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gluzman Y. Cell. 1981;23:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma H, Shang Y, Lee DY, Stallcup MR. Methods Enzymol. 2003;364:284–296. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)64016-4. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JH, Li H, Stallcup MR. MolCell. 2003;12:1537–1549. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noma K, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Science. 2001;293:1150–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.1064150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litt MD, Simpson M, Gaszner M, Allis CD, Felsenfeld G. Science. 2001;293:2453–2455. doi: 10.1126/science.1064413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vakoc CR, Mandat SA, Olenchock BA, Blobel GA. Molecular Cell. 2005;19:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carling T, Kim KC, Yang XH, Gu J, Zhang XK, Huang S. MolCell Biol. 2004;24:7032–7042. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7032-7042.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayasam GV, Wendling O, Angrand PO, Mark M, Niederreither K, Song L, Lerouge T, Hager GL, Chambon P, Losson R. EMBO J. 2003;22:3153–3163. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang N, vom Baur E, Garnier JM, Lerouge T, Vonesch JL, Lutz Y, Chambon P, Losson R. EMBO J. 1998;17:3398–3412. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]