Ocular ischaemic syndrome (OIS) may present as an asymmetric retinopathy in diabetic patients. We report a case of asymmetric diabetic retinopathy with posterior segment neovascularisation due to OIS associated with critical ipsilateral carotid stenosis where the neovascularisation resolved after carotid endarterectomy.

Case report

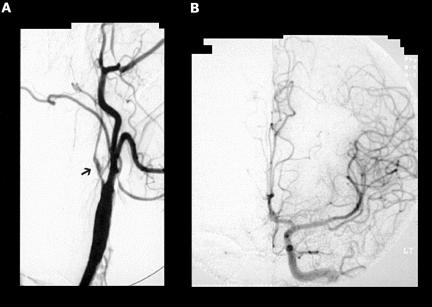

A 50 year old woman presented in May 1996 with left sided weakness. She had hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, a family history of vascular disease, and was a smoker. She was found to be diabetic with peripheral retinal ischaemia and disc neovascularisation in the right eye, and minimal retinal ischaemia in the left eye (Fig 1). Her visual acuities were 6/12 in the right eye and 6/9 on the left. There was no anterior segment neovascularisation in either eye. Carotid Doppler and carotid angiography showed critical stenosis at the origin of the right internal carotid artery. The right middle cerebral artery branches were visualised as a result of retrograde flow through the ophthalmic artery. The left internal carotid artery was narrowed by 50% and there were no collaterals to the right hemisphere (Fig 2). Fluorescein angiography revealed a prolonged transit time with slow filling of choroidal and retinal vasculature, peripheral retinal capillary closure, and leakage from the disc neovascularisation.

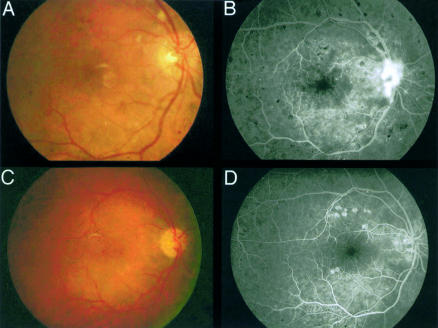

Figure 1.

Presenting fundus photograph showing disc neovascularisation (A) with corresponding fluorescein angiogram showing leakage from these vessels (B). The neovascularisation has resolved 14 months after surgery (C) and is confirmed on fluorescein angiography (D).

Figure 2.

Angiography showing narrowing of the right internal carotid artery (A, arrow) and angiogram of the left side (B) revealing lack of crossflow to the right cerebral hemisphere allowing the development of collateral circulation via the ophthalmic artery.

One year later the optic disc neovascularisation and retinal ischaemia were unchanged with no iris neovascularisation. In April 1997 she underwent an uneventful right carotid endarterectomy. Two months later she developed clinically significant macular oedema in the right eye that was treated with focal argon laser photocoagulation.

Six months later the maculopathy had resolved and 14 months after surgery there was complete resolution of the optic disc neovascularisation. Three years after surgery the right eye had a visual acuity of 6/9, a near normal fluorescein angiogram transit time, minimal peripheral retinal ischaemia, and no posterior segment neovascularisation.

Comment

Ocular ischaemic syndrome (OIS) is characterised in the anterior segment by flare and initial hypotony, with later iris neovascularisation. Retinopathy with neovascular proliferation occurs in the fundus because of chronic hypoperfusion. The development of neovascular glaucoma can lead to permanent blindness.1,2 In the diabetic patient OIS is superimposed on any pre-existing diabetic retinopathy, and markedly asymmetric retinopathy should prompt a search for underlying ischaemia from carotid occlusive disease. Diabetic patients with marked proliferative changes require treatment with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP), which has been shown to reduce the risk of severe visual loss and neovascular glaucoma. However, there is no clear evidence for the benefit of PRP in patients with OIS. In one study only 36% of OIS patients with iris neovascularisation responded to PRP, which may be due to uveal rather than retinal ischaemia.3,4 In the case presented the patient was not treated with immediate PRP but reviewed regularly. The disc new vessels did not progress in the year before carotid endarterectomy and there was no immediate threat to vision.

Carotid stenosis can result in changes in the ophthalmic artery blood flow ranging from reduced antegrade to reversal of flow. If there is inadequate crossflow in the circle of Willis from the contralateral internal carotid, reversal of flow occurs in the ophthalmic artery as a consequence of a collateral circulation from branches of the external carotid artery.5 Although some series show no correlation between direction of flow and the severity of OIS Kerty et al in a study of 45 patients found that only reversal of flow was associated with structural changes of OIS. 6

One similar case exists in the literature where neovascularisation resolved within several days of carotid endarterectomy (CEA).7 Other case reports also show that the retinopathy without neovascularisation can improve following surgery. However, the benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with ocular ischaemic syndrome is not quantified and it has never been shown to reverse neovascular glaucoma.8–10 The European Carotid Surgery Trial showed that the risk of ischaemic stroke in symptomatic patients with 70–99% carotid stenosis with medical treatment was only 20% over 3 years and CEA lowered this by 50%. Based on the results of this a risk factor score suggested that a cerebral rather than an ocular event had a greater risk for stroke on medical treatment and would therefore derive greater benefit from surgery.2

In the absence of iris neovascularisation and severe peripheral retinal ischaemia the ocular changes in patients with OIS can be monitored closely for the development of iris neovascularisation but the retinal vascularisation may not require early treatment with PRP.

References

- 1.Brown G, Magargal L. The ocular ischaemic syndrome. Clinical, fluorescein angiographic and carotid angiographic features. Int Ophthalmol 1988;11:239–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malhotra R, Gregory-Evans K. Management of ocular ischaemic syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:1428–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizener JB, Podhajsky P, Hayreh SS. Ocular ischaemic syndrome. Ophthalmology 1997;104:859–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sivalingam A, Brown GC, Magargal LE. The ocular ischemic syndrome. III. Visual prognosis and the effect of treatment. Int Ophthalmol 1991;15:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riordan-Eva P, Restori M, Hamilton AMP, et al. Orbital ultrasound in the ocular ischaemic syndrome. Eye 1994;8:93–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerty E, Eide N, Horven I. Ocular hemodynamic changes in patients with high-grade carotid occlusive disease and development of chronic ocular ischaemia II. Clinical findings. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1995;73:72–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neupert JR, Brubaker RF, Kearns TP, et al. Rapid resolution of venous stasis retinopathy after carotid endarterectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 1976;81:600–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearns TP, Younge BR, Piepgras DG. Resolution of venous stasis retinopathy after carotid endarterectomy. Mayo Clin Proc 1980;55:342–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ino-ue M, Azumi A, Kaijura-Tsukahara Y, et al. Ocular ischemic syndrome in diabetic patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1999;43:31–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geroulakos G, Bothchway L, Pai V, et al. Effect of carotid endarterectomy on the ocular circulation and on ocular symptoms unrelated to emboli. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1996;11:359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]