Henoch-Schonlein (H-S) purpura is an acute leucocytoclastic vasculitis that primarily affects children and mainly involves skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract, and kidney.1 Reported ophthalmic manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein purpura include episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, anterior uveitis, and central retinal vein occlusion.2–4 However, central retinal artery occlusion, to the best of our knowledge, have not been reported. We report on a girl with H-S purpura complicated with bilateral central retinal artery occlusion.

Case report

A 6 year old girl visited our paediatric department with the chief complaint of multiple erythematous rashes over the lower extremities and buttock for 2 weeks. Under a presumptive diagnosis of H-S purpura, oral prednisolone was prescribed. Nevertheless, arthralgia, haematuria, and moderate hypertension developed 3 weeks later. The histopathological findings of renal biopsy were compatible with H-S purpura nephritis. Unfortunately, acute renal failure occurred despite aggressive systemic treatment and haemodialysis was started.

Two days before haemodialysis, the patient noticed sudden visual loss. Visual acuity was hand movement in both eyes. Anterior segment and intraocular pressure were normal. Fundus examination revealed a cherry red spot with severe retinal oedema at the macular and peripapillary area in both eyes. Disc oedema and venous engorgement were also noted in both eyes (Figs 1 and 2). The retinal manifestations were compatible with bilateral central retinal artery occlusion. Fundus fluorescein angiography was not performed because of her poor general condition.

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph of the right eye demonstrating cherry red spot with severe retinal oedema at macular and peripapillary area, disc oedema, and venous engorgement.

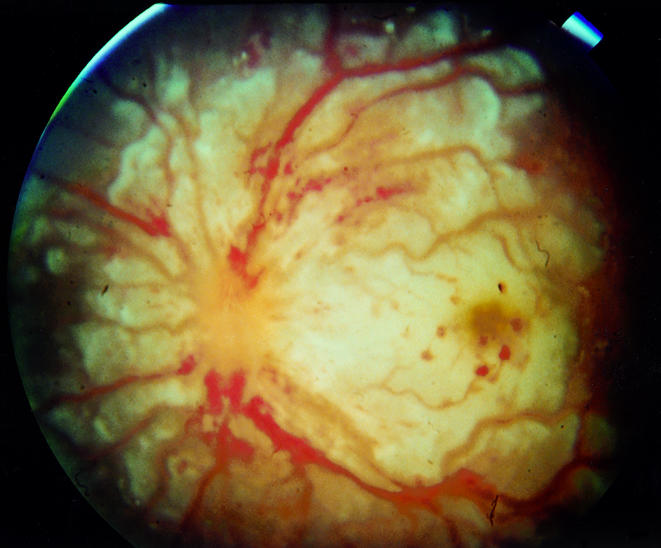

Figure 2.

Fundus photograph of the left eye demonstrating cherry red spot with severe retinal oedema at macular and peripapillary area, disc oedema, and venous engorgement.

Three days after haemodialysis, her systemic condition deteriorated with drowsiness that was proved to be cerebral vasculitis by brain computed tomography.

One month later, her visual acuity was counting finger in both eyes. Fundus examination revealed a pale disc, arterial sheathing, and drusen-like RPE change at foveal area in both eyes. Six months later, her best correction visual acuity was 6/30 in the right eye, and 6/60 in the left.

Comment

The dominant clinical manifestations of H-S purpura are cutaneous purpura (100%), abdominal pain (63%), gastrointestinal bleeding (33%), and nephritis (40%).2 In general, H-S purpura is an acute, self limiting illness though one third of patients will have one or more recurrences of symptoms. H-S purpura was the cause of renal failure in 2% and 5% of groups of children undergoing haemodialysis in California and France, respectively.5 Although the aetiology of H-S purpura remains unknown, it is clear that IgA has a critical role in the immunopathogenesis. The clinical features of H-S purpura are a consequence of widespread leucocytoclastic vasculitis due to IgA deposition in vessel walls.6 Treatment is limited to symptomatic and supportive care. Corticosteroids are often used depending on the severity of the disease.

According to the previous reports, the ocular manifestations of H-S purpura are rare, including episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, anterior uveitis, and central retinal vein occlusion.2–4 In this case, H-S purpura vasculitis may have an important role in the pathogenesis of bilateral central retinal artery occlusion. To our knowledge this might be the first case of H-S purpura complicated with bilateral central retinal artery occlusion in the literature.

References

- 1.Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Pediatric Dermatol 1984;1:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schonlein purpura in children. Report of 100 patients and review of the literature. Medicine 1999;78:395–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamabe H, Ozawa K, Fukushi K. IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis with anterior uveitis. Nephron 1988;50:368–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton CH, Vaziri ND. Central retinal vein occlusion associated with hemodialysis. Am J Med Sci 1979;277:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farley TA, Gillespie S, Rasoulpour M. Epidemiology of a cluster of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Am J Dis Child 1989;143:798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen AC, Willis FR, Beattie TJ. Abnormal IgA glycosylation in Henoch-Schonlein purpura restricted to patients with clinical nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998;13:903–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]