Intracranial arteriovenous malformations are capable of spontaneous regression.1–3 There are also numerous recorded events of vascular remodelling, thrombosis, and autoinvolution in retinal arteriovenous malformations.4–7 This report documents a self obliterated retinal arteriovenous malformation in a patient with Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome who developed neurological symptoms due to spontaneous regression of the intracranial component of the angiomatous malformation.

Case Report

A 32 year old man from Guam was evaluated for a history of right parietal headaches for several months and acquired temporal hemianopia in the left eye. He had a history of blindness in the right eye from early childhood, and had recently become aware of a temporal hemianopia in the left eye.

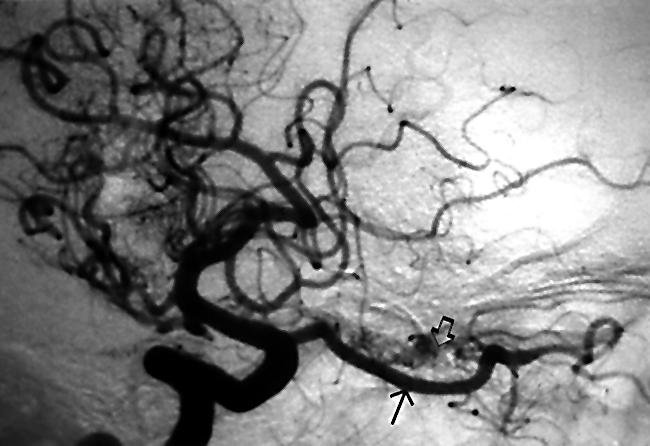

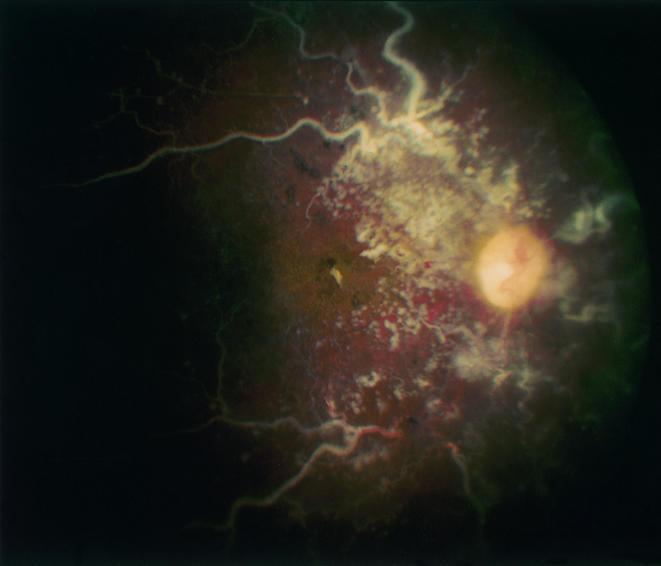

Visual acuity was no light perception in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. The right pupil was unreactive to light. The left pupil was sluggishly reactive and there was a right afferent pupillary defect. Slit lamp examination showed conjunctival venous engorgement in the right eye. Retinal examination disclosed white, sclerotic major retinal vessels, with no evidence of retinal vascular perfusion in the right eye (Fig 2). The major retinal vessels were surrounded by non-perfused clusters of white, racemose, telangectatic, vessels (Fig 1). The left optic nerve showed band atrophy with corresponding nerve fibre layer dropout but no other retinal abnormality.

Figure 2.

Internal carotid artery angiogram, arterial phase, demonstrating marked enlargement of the ophthalmic artery (bottom right, arrow). The right optic nerve is honeycombed by a vascular malformation (open arrow).

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph of right eye demonstrating self obliterated retinal arteriovenous malformation. Sclerotic major retinal vessels are surrounded by smaller racemose ghost vessels.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed numerous vascular channels permeating the right basal ganglia, anterior portion of the midbrain, prefrontal gyrus, optic chiasm, and the right orbit. The deep hemispheric portion of the lesion showed surrounding oedema. CT scanning showed punctate and conglomerate calcifications in the malformation, as well as enlargement of the right optic canal. Cerebral angiography demonstrated an angiomatous vascular malformation that permeated the basal ganglia as well as the optic chiasm region and extended into the right orbit (Fig 2). There was a relative lack of deep venous drainage in the chiasmatic region of the malformation, with diversion to the Sylvian vein system and over the convexities to the sagittal sinus. The lack of hypertrophy in these draining venous channels, together with the regional oedema on magnetic resonance imaging, suggested a recent obstruction of vascular flow within the angiomatous malformation.

Comment

The syndrome of unilateral retinocephalic arteriovenous malformation was first described in 1937 by Bonnet et al.8 Six years later, Wyburn-Mason published his report in the English language.9 These congenital unilateral retinocephalic arteriovenous malformations may involve the visual pathways from the retina and optic nerve to the ipsilateral occipital cortex, and may involve the chiasm, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, midbrain, and cerebellum.10 Since these arteriovenous malformations are high flow systems in which veins are exposed to arterial blood pressures, they are susceptible to turbulent blood flow and to vessel wall damage which can lead to thrombosis and occlusion.7 Over time, components of an angiomatous malformation can grow, haemorrhage, sclerose, thrombose, and involute.7

Our patient had longstanding involution of his retinal arteriovenous malformation, with new neurological symptoms resulting from thrombosis of the intracranial component of the tumour. Spontaneous occlusion of the major venous drainage within the deep cerebral hemisphere and optic chiasm may have caused headaches by producing regional oedema or by diverting flow to other venous structures. Since the major venous drainage within the malformation was already occluded at the time of presentation, no treatment was advised. The complex evolution of clinical signs in our patient underscores the need to distinguish disease progression from spontaneous involution in symptomatic patients with Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

References

- 1.Höök O, Johanson C. Intracranial arteriovenous aneurysm. A follow-up study with particular attention to their growth. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatr 1958;80:39–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conforti P. Spontaneous disappearance of cerebral arteriovenous angioma. Case report. J Neurosurg 1971;34:432–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin J, Misko JC, Seres JL, et al. Spontaneous angiographic disappearance of a cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Third reported case. Arch Neurol 1973;28:195–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekking HM. Arteriovenous aneurysm of the retina with spontaneous regression. Ophthalmologica 1955;130:113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augsburger JJ, Goldberg RE, Shields JA, et al. Changing appearance of retinal arteriovenous malformation. Albrecht von Graefes Arch Klin Ophthalmol 1980;215:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansour AM, Wells CG, Jampol LM, et al. Ocular complications of arteriovenous communications of the retina. Arch Ophthalmol 1989;107:232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schatz H, Chang LF, Ober RR, et al. Central retinal vein occlusion associated with retinal arteriovenous malformation. Ophthalmology 1993;100:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnet P, Dechaume J, Blanc E. L'anévrysme cirsoïde de la rétine (anévrysme recémeux): ses relations avec l'anéurysme cirsoïde de la face et avec l'anévrysme cirsoïde du cerveau. J Med Lyon 1937;18:165–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyburn-Mason R. Arteriovenous malformation of the mid-brain and retina, facial naevi, and mental changes. Brain 1943;18:165–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Théron J, Newton TH, Hoyt WF. Unilateral retinocephalic vascular malformations. Neuroradiology 1974;7:185–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]