Chickenpox in children is usually thought of as a benign infectious disease with few ocular complications. Posterior segment involvement from primary varicella zoster infection has rarely been reported in children. We describe the clinical features and visual outcome of an unusual case of neuroretinitis presenting in a 9 year old child.

Case report

An immunocompetent 9 year old boy acquired primary varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection from his sibling and developed the characteristic exanthematous vesicular rash. Four days after the onset of the rash he woke with discomfort in his right eye and described his vision as being “all grey” on that side. He presented to the emergency department the same day and was found to have a visual acuity of 3/6 on the right and 3/3 on the left (logMAR). A relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) was present on the right. His anterior segment was quiet with no vitritis; however, he had slight macular thickening and a subtle cherry red spot on funduscopy, along with some mild peripapillary swelling and disc haemorrhage.

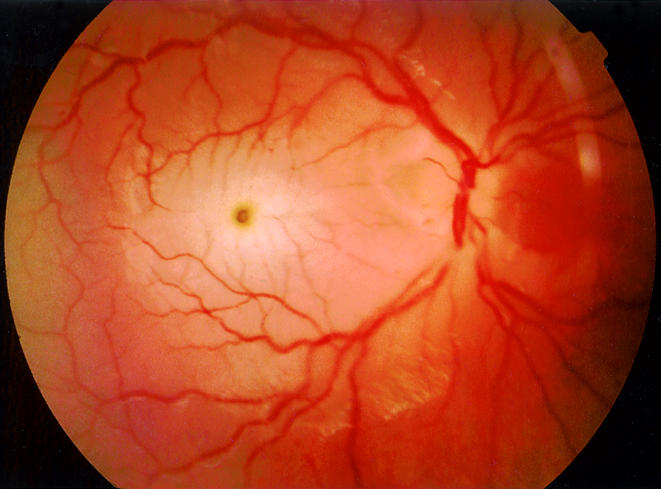

On review in the ophthalmology clinic 2 days later his vision had reduced to 1/60 (Sheridan Gardiner singles) on the right. He had no new skin lesions and all those present had crusted. No lid lesions were present. He had a marked RAPD, red desaturation, and mild conjunctival injection. His anterior segment and vitreous remained clear. The right disc was hyperaemic with peripapillary swelling and haemorrhage. The macular area was pale and oedematous (Fig 1). Examination of the left eye was completely normal.

Figure 1.

Right fundus: neuroretinitis with loss of vision to 1/60.

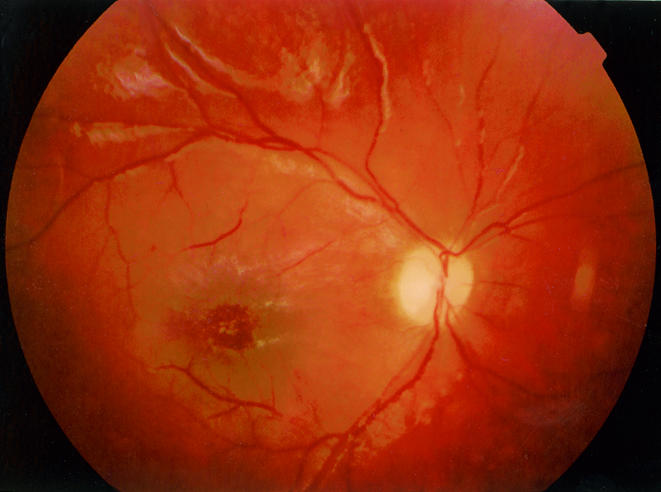

Considering the onset of ocular symptoms and signs following the appearance of the typical VZV skin lesions, a presumptive diagnosis of chickenpox neuroretinitis was made. He was admitted and commenced on intravenous aciclovir (250 mg × 3 per day). Confirmatory IgM titres for VZV were unfortunately not performed. No change in his acuity was observed over the next few days; however, his right disc was noted to become slightly pale after 2 days of treatment. At this point intravenous methyl prednisolone was instituted at a dose of 5 mg/kg per day. Despite a gradual resolution of the macular and peripapillary oedema over the next 5 days, his disc remained pale (Fig 2) and his acuity measured as 3/30 (logMAR) after 7 days of intravenous aciclovir and 5 days of methyl prednisolone. Systemically he remained completely well and afebrile on treatment. He was discharged with a further 3 day course of oral aciclovir and a 6 day reducing course of oral prednisolone.

Figure 2.

Right fundus: following treatment with intravenous aciclovir and methyl prednisolone.

Over 5 months of follow up his acuity has not improved beyond 3/30 (logMAR). The right optic disc is pale and a yellow lipid deposit is present at the macula with some reticular macular pigmentation. The left eye has been normal throughout.

Comment

Posterior segment involvement as part of primary VZV infection in children has only been reported twice to our knowledge. Copenhaver1 reported a 3 year old with bilateral papillitis and a unilateral macular lesion associated with encephalitis following VZV infection. In this case there was complete recovery of vision and resolution of the macular lesion within 3 weeks of presentation. Capone and Meredith2 describe a case of unilateral central visual loss in a 2 year old child caused by chickenpox retinitis with optic neuritis resulting in a poor visual outcome. Their patient presented with an acute exotropia 24–48 hours before the onset of cutaneous VZV. Funduscopy revealed papillitis, phlebitis, and a macular lipid star; retinal opacification just outside the arcades and scattered intraretinal haemorrhages were also described. In these two cases sequential acuity measurement or photography were not possible because of the young age of the subjects.

Our case is particularly interesting, not only because these are the first published fundal photographs of VZV neuroretinitis in a child, but also because of the relatively mild ocular findings which have resulted in severe visual loss. The young age of the patient is atypical of ocular VZV infection.3 Adults who contract primary VZV infection tend to run a more severe course than children.4 Ocular complications in children are extremely rare.5

The typical posterior segment involvement of VZV is acute retinal necrosis (ARN).4 The youngest case of ARN in association with chickenpox has been reported in a 4 year old.5 In adults, ARN is described as being less severe when presenting at the time of primary zoster infection than as a result of secondary reactivation of latent, previously acquired VZV.6 The changes typical of ARN were absent in this case. Unilateral papillitis and retinitis confined to the macular area were the main features. Optic neuritis has been reported by several authors in association with primary VZV.7–9 Many of these cases are bilateral and coincident with encephalitis7 or occurring in those who are immunocompromised.8 Unilateral optic neuritis has been described in an 18 year old several weeks following a varicella rash which remitted without sequelae following the administration of corticosteroid.9

The mainstay of treatment of VZV retinitis is with intravenous aciclovir. Whether any advantage is gained in administering systemic steroid with the aciclovir is controversial.4 We do not know if a more positive visual outcome may have been achieved if intravenous therapy had been commenced on presentation. It is therefore suggested that prompt treatment of VZV retinitis with intravenous aciclovir be started in patients, particularly in a child, presenting with any posterior segment signs.

References

- 1.Copenhaver RM. Chickenpox with retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1966; 75:199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capone A, Meredith TA. Central visual loss caused by chickenpox retinitis in a 2-year-old child. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;113:592–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Gelder RN, Willig JL, Holland GN, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 as a cause of acute retinal necrosis syndrome in young patients. Ophthalmology 2001;108:869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoser SL, Forster DJ, Rao NA. Systemic viral infections and their retinal and choroidal manifestations. Surv Ophthalmol 1993; 37:313–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee WH, Charles SJ. Acute retinal necrosis following chickenpox in a healthy 4 year old patient. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:667–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culbertson WW, Brod RD, Flynn HW, et al. Chickenpox-associated acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1641–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selbst RG, Selhorst JB, Harbison JW, et al. Parainfectious optic neuritis. Report and review following varicella. Arch Neurol 1983;40:347–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MS, Cooney EL, Stoessel KM, et al. Varicella zoster virus retrobulbar optic neuritis preceding retinitis in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology 1998;105:467–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pina MA, Ara JR, Capablo JL, et al. Myelitis and optic neuritis caused by varicella. Rev Neurol 1997;25:1575–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]