Abstract

Background/aim: Amniotic membrane (AM) transplantation effectively expands the remaining limbal epithelial stem cells in patients with partial limbal stem cell deficiency. The authors investigated whether this action could be produced ex vivo.

Methods: The outgrowth rate on AM was compared among explants derived from human limbus, peripheral cornea, and central cornea. For outgrowth of human limbal epithelial cells (HLEC), cell cycle kinetics were measured by BrdU labelling for 1 or 7 days, of which the latter was also chased in primary cultures, secondary 3T3 fibroblast cultures, and in athymic Balb/c mice following a brief treatment with a phorbol ester. Epithelial morphology was studied by histology and transmission electron microscopy, and phenotype was defined by immunostaining with monoclonal antibodies to keratins and mucins.

Results: Outgrowth rate was 0/22 (0%) and 2/24 (8.3%) for central and peripheral corneal explants, respectively, but was 77/80 (96.2%) for limbal explants (p <0.0001). 24 hour BrdU labelling showed a uniformly low (that is, less than 5%) labelling index in 65% of the limbal explants, but a mixed pattern with areas showing a high (that is, more than 40%) labelling index in 35% of limbal explants, and in all (100%) peripheral corneal explants. Continuous BrdU labelling for 7 days detected a high labelling index in 61.5% of the limbal explants with the remainder still retaining a low labelling index. A number of label retaining cells were noted after 7 day labelling followed by 14 days of chase in primary culture or by 21 days of chase after transplantation to 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers. After exposure to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 24 hours and 7 day labelling, HLEC transplanted in athymic mice still showed a number of label retaining basal cells after 9 days of chase. HLEC cultured on AM were strongly positive for K14 keratin and MUC4 and slightly positive in suprabasal cells for K3 keratin but negative for K12 keratin, AMEM2, and MUC5AC. After subcutaneous implantation in athymic mice, the resultant epithelium was markedly stratified and the basal epithelial cells were strongly positive for K14 keratin, while the suprabasal epithelial cells were strongly positive for K3 keratin and MUC4, and the entire epithelium was negative for K12 keratin and MUC5A/C.

Conclusions: These data support the notion that AM cultures preferentially preserve and expand limbal epithelial stem cells that retain their in vivo properties of slow cycling, label retaining, and undifferentiation. This finding supports the feasibility of ex vivo expansion of limbal epithelial stem cells for treating patients with total limbal stem cell deficiency using a small amount of donor limbal tissue.

Keywords: amniotic membrane, ex vivo expansion, limbus, epithelium, stem cell, cell cycle kinetics, stem cell transplantation

Stem cells (SC) of the corneal epithelium have been found to be located exclusively at the limbus—that is, the anatomical junction between the cornea and the conjunctiva.1 Limbal epithelial SC are the ultimate source of regeneration of the entire corneal epithelium under both normal and injured states (reviewed in Tseng2). Studies of the epithelial phenotype have shown that the limbal basal epithelium does not express corneal epithelial specific keratin 31 or keratin 12.3,4 Studies of the cell cycle kinetics have shown that some portions of the limbal basal epithelial cells are slow cycling5,6 and label retaining.5,7 Other studies have further confirmed that limbal epithelial SC have a greater growth potential in explant cultures8 and higher clonogenicity when co-cultured on 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers,9–13 and that their proliferative potential is resistant to tumour promoting phorbol esters.5,7,14

When the SC containing limbal epithelium is partially15,16 or totally17,18 damaged, the corneal surface is invariably covered by ingrowing conjunctival epithelial cells with goblet cells, and the corneal stroma becomes vascularised with chronic inflammation. These pathological signs signify a process of conjunctivalisation and constitute the basis for the diagnosis of a number of corneal disease with limbal SC deficiency19 (for reviews see Tseng2 and Tseng and Sun20). Transplantation of an autologous or allogeneic source of limbal epithelial SC is necessary to restore vision and the normal corneal surface in these diseases (for reviews see Tseng21 and Holland and Schwartz22).

Previously, preserved human amniotic membrane (AM) has been transplanted as a substrate together with transplantation of limbal epithelial SC for treating these limbal SC deficient corneas.23–27 Interestingly, we noted that AM transplantation alone is sufficient to restore the corneal surface in which the limbus has been partially damaged,26,28 suggesting that AM may help expand the residual limbal epithelial SC. Recently, clinical29,30 and experimental31 studies have also shown that ex vivo expanded limbal epithelial cells on AM are capable of restoring the corneal surface with limbal SC deficiency. We provide here additional evidence that AM might be an ideal matrix for ex vivo preservation and expansion of limbal epithelial SC. The significance of this finding for improving clinical efficacy of transplanting limbal epithelial SC is further discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All procedures were performed according to the ARVO statement for the use of animals in ophthalmic and vision research. Balb/c athymic mice, aged 6–10 weeks, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, NC, USA). The mice were housed conventionally under temperature, humidity, and light (12 hour light cycle; lights on at 7 am) controlled conditions in filter covered cages and were kept on standard chow and water ad libitum. Before surgery, mice were anaesthetised by intramuscular injection of 14 mg/kg ketamine and 7 mg/kg xylazine and were killed by cervical dislocation.

Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), HEPES-buffer, trypsin-EDTA, amphotericin B, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). Dispase II and FITC conjugated and affinity purified goat anti-mouse IgM antibody were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapalis, IN, USA). The IgG monoclonal antibody AE5, recognising the 64 kD keratin K31 was purchased from ICN (Costa Mesa, CA, USA). The mouse monoclonal IgG antibody 15H10 directed against MUC432 was a kind gift from Kermit Carraway, PhD (University of Miami, FL, USA). The mouse monoclonal IgG antibody 19M1 directed against MUC5AC33 was a kind gift from Jacques Bara, MD (Paris, France). The FITC conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and IgM antibodies adsorbed with human serum proteins, the mouse monoclonal IgG antibody against 5 bromo 2' desoxyuridine 5'monophosphate (BrdU), BrdU, gentamicin, hydrocortisone, dimethylsulphoxide, cholera toxin (subunit A), insulin transferrin sodium selenite media, and phorbol 12 myristate 13 acetate (PMA) were all from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, USA). The mouse monoclonal antibodies AK2 to K12 keratin3,4 and AMEM2 to mucosal epithelial membrane associated glycocalyx34 were of the IgM class and developed in our laboratory. The mouse monoclonal antibody against keratin K14 was from Novocastra (Burlingame, CA, USA). The Vectastain Elite ABC Kit for mouse IgG was obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). The tissue culture plastic plates (six well) were from Becton Dickinson (Lincoln Park, NJ, USA). Culture plate inserts used for fastening AM were from Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA). The anti-mouse lymphocyte serum was purchased from Accurate Chemicals Co (Westbury, NY, USA).

Explant cultures on amniotic membrane

Human tissue was handled according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Corneoscleral tissues from human donor eyes, aged 30–50 years, were obtained from the Florida Lions Eye Bank (Miami, FL, USA). The tissue was rinsed three times with DMEM containing 50 μg/ml gentamicin and 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin B. After careful removal of excessive sclera, iris, corneal endothelium, conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule, the remaining tissue was placed in a culture dish and exposed for 5–10 minutes to Dispase II (1.2 U/ml in Mg2+ and Ca2+ free Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS)) at 37°C under humidified 5% carbon dioxide. Following one rinse with DMEM containing 10% FBS, the tissue was subdivided by a trephine into three portions—that is, the central cornea (7.5 mm in diameter), the peripheral cornea (7.5 mm to 1 mm within the limbus), and the limbus (the remainder). Each of these three portions was then cut into cubes of approximately 1 × 1.5 × 2.5 mm by a scalpel.

Preserved human AM was kindly provided by Bio Tissue (Miami, FL, USA), and fastened onto a culture insert as recently reported.35 On the centre of AM a tissue cube was placed (Fig 1A) and cultured in a medium described by Jumblatt and Neufeld36 made of an equal volume of HEPES buffered DMEM containing bicarbonate and Ham's F12, and supplemented with 5% FBS, 0.5% dimethyl sulphoxide, 2 ng/ml mouse EGF, 5 μg/ml insulin, 5 μg/ml transferrin, 5 ng/ml selenium, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 30 ng/ml cholera toxin, 5% FBS, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin B. Cultures were incubated at 37°C under 5% carbon dioxide and 95% air and the medium was changed every 2–3 days while the extent of each outgrowth was monitored with a phase contrast microscope.

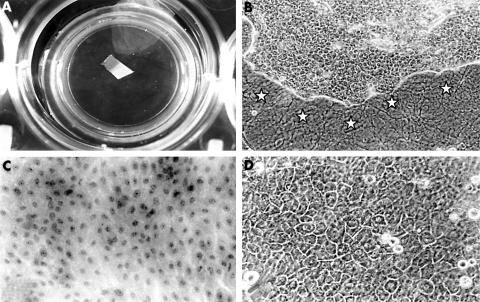

Figure 1.

HLEC growth on AM culture system. (A) The explant was placed in the centre of AM, which was fastened onto a culture insert. (B) One week after culturing HLEC outgrowth was noted (with the border marked with stars). (C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining, and (D) phase contrast image of a representative cell culture exhibiting a cohesive sheet of uniformly small, cuboidal, and compactly basal epithelial cells. Magnification: 40× (B) and 200× (C, D).

BrdU labelling

When the outgrowth reached 5–8 mm in diameter, explant cultures were incubated with a fresh medium containing 10 μM BrdU for 1 (n = 20 for the limbus and n = 2 for the peripheral cornea) or 7 days (n = 13 for the limbus). Some limbal cultures (limbus: n = 4) after 7 day labelling were chased for 14 days by switching to the BrdU free medium. A separate experiment was carried out by transplanting an AM sheet of 6 mm diameter which contained the HLEC outgrowth with 7 day BrdU labelling, to a secondary culture (n=10), which had been laid down with a mitomycin C treated 3T3 fibroblast feeder layer prepared in a conventional manner,12 and then chased for 14 days. All samples were fixed in cold methanol and processed for immunostaining. In a subset of experiments HLEC on AM (n = 7) were treated for 24 hours with 1.0 μg/ml PMA, and then continuously labelled with BrdU for 7 days. Four cultures were processed directly for immunostaining, while the remaining three were subcutaneously transplanted in nude mice (see below) and chased for 9 days in vivo.

Subcutaneous implantation in athymic Balb/c mice

Because our preliminary experiments showed that subcutaneous implantation in athymic Balb/c mice showed a striking non-specific inflammatory response with macrophages around the abdominal rectus muscle, we found it necessary to tame such inflammation by intraperitoneal injections of 0.5 ml anti-mouse lymphocyte serum37–39 1 day before and 2 days after implantation.

After the skin covering the rectus abdominis was undermined to expose an area measuring approximately 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm, HLEC cultured on AM for 2–3 weeks were implanted subcutaneously onto the fascial surface of the muscle, and the skin flap was then closed with a running, coated Vicryl 7-0 suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). Postoperatively, gentamicin ointment was applied once daily on the wound. A firm subcutaneous nodule formed during an 8 day period was excised together with the surrounding skin and the muscle for histology and immunostaining.

Immunostaining

For BrdU labelling, the flat mount preparation of the epithelial outgrowth on AM was used directly, and the tissue from athymic mice was subjected to frozen sections of 6 μm thickness in OCT (Tissue Tek, Sakura FineTEK, Torrance, CA, USA). After the sample was air dried, rehydrated for 5 minutes in PBS, treated with 2N HCl at 37°C for 60 minutes to denature DNA, and neutralised in boric acid (pH 8.5) for 20 minutes, incorporated BrdU was detected by immunostaining with a mouse anti-BrdU antibody followed by a Vectastain Elite Kit which was processed according the recommendations of the manufacturer. The slides were finally counterstained with eosin. Under 400× magnification, positive nuclei were counted among the total nuclei within the entire field, and a total of two to four fields were counted per specimen. The labelling index was expressed as the number of positively labelled nuclei/the number of all nuclei × 100%.

For other immunostaining work, sections were preincubated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide to eliminate endogenous peroxidase, and with goat serum (1:1000) to prevent non-specific staining. After rinsing twice for 5 minutes with PBS, they were incubated with each of the following mouse monoclonal antibodies with respective dilution: AE5 (1:100), AK2 (1:500), K14 (1:40), AMEM2 (1:300), MUC4 (1:400), and MUC5AC (1:100). After twice washing with PBS for 5 minutes, they were incubated with an FITC conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG at 1:100 for K14, AE5, MUC4, and MUC5AC or goat anti-mouse IgM at 1:100 for AK2 and AMEM2). After two additional PBS washes, sections were mounted with an anti-fade solution and analysed with a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Transmission electron microscopy

Selected specimen were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 1% formaldehyde and processed for conventional transmission electron microscopy. Samples were rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3), postfixed in 1% osmium tretroxide, and embedded in Epon. Semithin sections were stained with 1% methylene blue, 1% Azure II, and 1% borax. Ultrathin sections were cut and conventionally stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and finally examined with a Philips EM 420 electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

The differences in outgrowth rate between explant cultures from the limbus, peripheral, and central cornea were analysed with Fisher's exact test. Data from the proliferation assay were analysed by paired or unpaired Student's t test, as appropriate. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Epithelial morphology

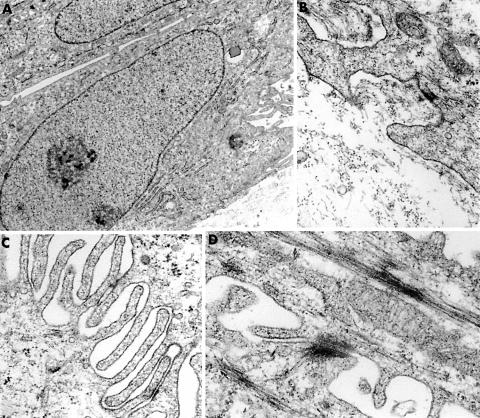

The rate of epithelial outgrowth was slow for the first week, but became rapid from then on and frequently reached a size of 2–3 cm in diameter in 2–3 weeks. The basal epithelial cells of the outgrowth of HLEC in 1 week was uniformly small, cuboidal, and with an areal ratio of close to 1:1 between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Fig 1B–D), similar to that of conjunctival epithelial cells grown in the same culture system.35 The outgrowth reached confluence—that is, the limit of the membrane fastened to a 35 mm insert, in 4–5 weeks. As with conjunctival epithelial cultures,35 the resultant epithelial sheet of HLEC cultures remained as two to four cell layers and had scanty cytoplasm in the basal cells (Fig 2A). Transmission electron microscopy showed that occasionally there were hemidesmosomes anchored in a rudimental to partially developed basement membrane of AM (Fig 2B), a finding similar to that was recently reported.29 In these presumably basement membrane deficient areas of AM, attachment of basal cells seemed to be mediated by microfibrillar structures and by protrusions of the basal cell membrane into the superficial stroma of AM (Fig 2B). Interestingly, these basal cells developed prominent intercellular digitation commonly seen in conjunctival, but not corneal, epithelial cells (Fig 2C). Formation of desmosomes was more pronounced in the superficial cell layers (Fig 2D). HLEC grown on AM could be maintained for more than 2 months during which time the majority of the basal HLEC still remained uniformly small, some cells increased intracytoplasmic vacuoles, and superficial cells showed desquamation.

Figure 2.

Ultrastructural appearance of HLEC on AM culture. (A) A basal cell with a scanty cytoplasm. (B) Hemidesmosomes anchored to a rudimentary to partially developed basement membrane of AM were infrequently observed. Attachment of the basal cell was in some areas mediated by small protrusions of its basal cell membrane into the superficial stroma of AM. (C) These basal cells developed intercellular digitation with poor formation of desmosomes. (D) Formation of desmosomes was more pronounced in the superficial cell layers. Magnification: 6350× (A); 36 000× (B); 30 000× (C); and 36 000× (D).

Epithelial phenotype

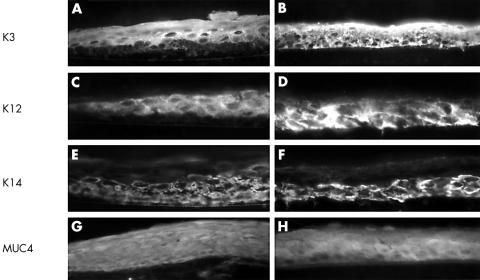

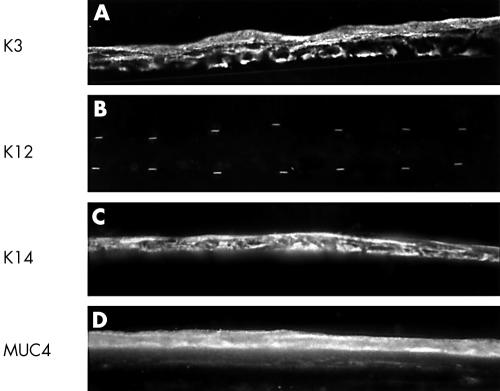

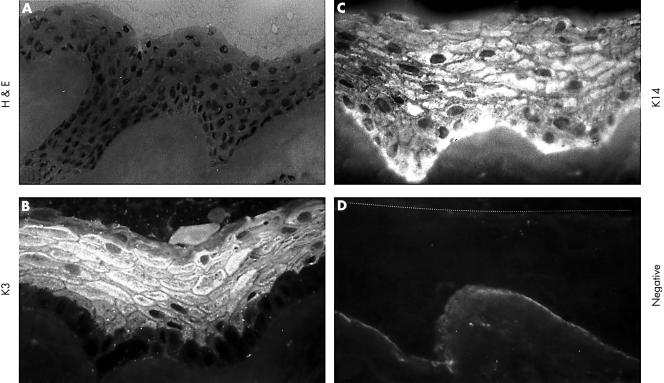

To examine the epithelial phenotype, we immunostained with a panel of monoclonal antibodies to mucins and keratins. To verify their antigenic epitopes, we first stained normal ocular surface epithelia in vivo. As reported,1 AE5 antibody, which recognises K3 keratin, stained the suprabasal limbal epithelium (Fig 3A) and the full thickness of the central corneal epithelium (Fig 3B), but not the conjunctival epithelium (not shown). AE5 antibody stained suprabasal HLEC cultured on AM for 13 or 21 days (Fig 4A). Immunostaining for K12 keratin by AK2 was also positive for limbal suprabasal epithelial cells (Fig 3C) and for the full thickness of the corneal epithelium (Fig 3D), but negative for the conjunctival epithelium in vivo. HLEC on AM were negative for AK2 (Fig 4B). K14 keratin was expressed in the basal and suprabasal cell layers of the conjunctival (not shown), limbal (Fig 3E) and peripheral corneal epithelium, but was predominantly in the basal epithelial cells of the central corneal epithelium (Fig 3F). HLEC cultured on AM showed full thickness staining to K14 keratin after 13 days (Fig 4C) and 21 days of culturing, when occasionally a stratified epithelium developed. MUC4 was found in vivo throughout the whole limbal (Fig 3G) and corneal (Fig 3H) epithelial layer. HLEC cultured on AM showed full thickness positive labelling with MUC4 after 13 and 21 days of culturing (Fig 4D). MUC5AC recognises conjunctival goblet cell secreted mucins and stains conjunctival goblet cells in vivo.32 MUC5AC did not stain any cells cultured on AM (not shown). AMEM 2 revealed a membrane bound staining throughout the corneal, limbal, conjunctival epithelial layer, with a stronger staining towards the apical ocular surface.15 AMEM 2 did not stain HLEC cultured on AM (not shown). Collectively, these results indicate that the resultant phenotype of HLEC grown on AM retained a limbal origin, was predominantly basal epithelial cells, and remained undifferentiated.

Figure 3.

Immunostaining of keratins K3 (A, B), K12 (C, D), and K14 (E, F), and MUC4 (G, H) in the normal limbal (A, C, E, and G) and corneal (B, D, F, and H) epithelium. K3 keratin and K12 keratin were expressed by the suprabasal limbal epithelium (A, C) and the full thickness of the central corneal epithelium (B, D). K14 keratin was expressed strongly in basal and suprabasal limbal (E) and predominantly basal corneal epithelium (F). MUC4 was expressed in the full thickness of the limbal (G) and corneal epithelium (H). The dotted line (A, C, and E) indicates the border between basal limbal epithelium and stromal tissue. Magnification: 400× (A–H).

Figure 4.

Immunostaining of keratins K3 (A), K12 (B), and K14 (C), and MUC4 (D) of HLEC grown on AM cultures. K3 keratin was expressed by suprabasal cell layers (A). K12 keratin was not expressed (B). K14 keratin was expressed by all cell layers (C). MUC4 was also expressed by all cell layers (D). The dotted line (A) indicates the extent of HLEC cultured on AM. Magnification: 40× (A–D).

Differentiation of human limbal epithelial cells after subcutaneous grafting into Balb/c athymic mice

To promote epithelial differentiation, we transplanted AM with HLEC outgrowth into the subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen in seven athymic Balb/c mice for 8 days. Excluding one dying of bleeding, four of the remaining six mice (66.6%) showed graft survival evidenced by the formation of a stratified epithelium resembling a normal limbal epithelium in vivo. Figure 5 depicts the stratified epithelium of a representative sample consisting of one layer of small round to cuboidal basal epithelial cells, three to four layers of wing cells, and three to four layers of flattened superficial layers (Fig 5A). The staining by AE5 antibody was negative in the basal cell layer, but positive in suprabasal and superficial epithelial cells (Fig 5B), a pattern identical to that of the normal human limbal epithelium. The staining by AK2 antibody was weakly positive in the superficial epithelial layers (not shown). The staining to K14 keratin was positive throughout the entire stratified epithelium including the basal cell layer (Fig 5C). MUC4 was diffusely expressed by all cell layers (not shown), a pattern also resembling that of the normal limbal epithelium in vivo. Staining for MUC5AC and by AMEM2 antibody was all negative (Fig 5D). Taken together, these data support the notion that subcutaneous transplantation in nude mice promotes epithelial stratification with proper differentiation into a phenotype resembling the normal limbal epithelium.

Figure 5.

HLEC on AM after subcutaneous implantation in athymic Balb/c mice. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin staining showed a markedly stratified epithelium with cuboidal basal epithelial cells. (B) K3 keratin was not expressed by the basal layer, but was strongly expressed by all suprabasal and superficial epithelial cells. (C) K14 keratin was expressed by all layers. (D) Negative control. The dotted line indicates the upper border of the stratified epithelium. Magnification: 200× (A); 400× (C, D).

Proliferation of ex vivo expanded HLEC

There were no outgrowths (0%) out of 22 central corneal explants tested, while there was some outgrowth in two out of 24 (8.3%) peripheral corneal explants. In contrast, abundant outgrowth was noted in 77 out of 80 (96.2%) limbal explants (p <0.0001, Fisher's exact test). These results suggest that AM preferentially supports the outgrowth of epithelial progenitor cells derived from the limbus.

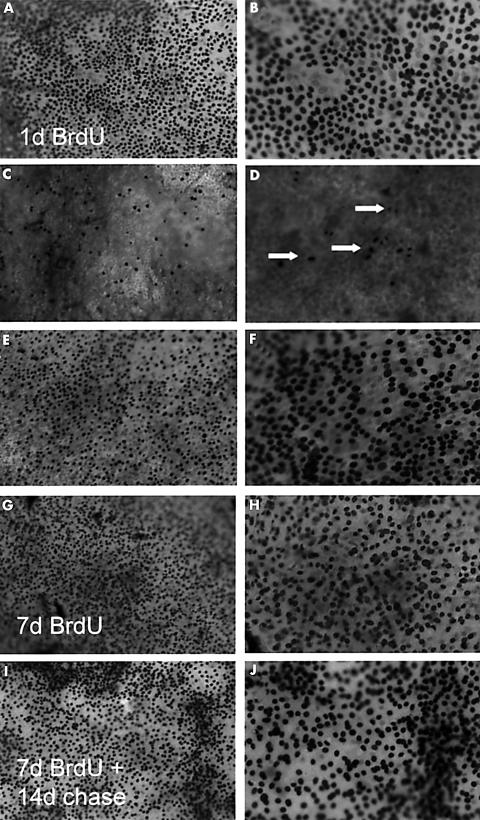

To determine the cell cycle, we labelled the S phase with BrdU, an analogue of thymidine, for 24 hours in 2–3 week old cultures. In all limbal explants tested, 35% of them had a mixed pattern with areas of a moderate high labelling index (mean 44.3% (SE 15.3%), n = 7) (Fig 6A and 6B), while the majority (65%) had a uniformly low labelling index (3.3% (3.3%), n = 13) (Fig 6C and 6D) (p<0.0001, unpaired t test). In contrast, the outgrowth from all (100%) peripheral corneal explants had a uniformly high labelling index (61.7% (2.2%), n=2) (Fig 6E and 6F), indistinguishable from that shown in Figure 6A and 6B. These results indicated that 24 hour BrdU labelling predominantly labelled rapid cycling progenitor cells in the peripheral cornea. The patchy pattern of high labelling index in some limbal explants might be caused by the inclusion of peripheral corneal transient amplifying cells. To confirm that the low labelling index of the limbal outgrowth was indeed a result of slow cycling progenitor cells but not because of post mitotic differentiated cells, we labelled a total of 13 limbal explants continuously for 7 days. The results showed that eight of them (61.5%) showed a high labelling index of 75.5% (10.9%) (Fig 6G and 6H), while the remaining five (38.5%) still showed a low labelling index of 10.01% (10.8%) (p<0.0001, unpaired t test). This result indicated that the majority of limbal epithelial explants had a slower cell cycle, and some of them had a cell cycle length longer than 7 days.

Figure 6.

Cell cycle analysis using BrdU labelling. After 24 hours of labelling (1d BrdU), 35% of all limbal explants tested had a mixed pattern with areas of relatively high labelling index (A, B), while the remaining 65% had a low labelling index (C, D). Arrows indicate those positive nuclei. All peripheral corneal explants had a uniformly high labelling index (E, F). After a continuous labelling for 7 days (7d BrdU), 61.5% of primary HLEC cultures showed a high labelling index (G, H), but the remainder still had a low labelling index (not shown). These 7 day labelled cultures were chased for 14 days, the label index remained high (I, J). Magnification: 100× (A, C, E, G, and I); 200× (B, D, F, H, and J).

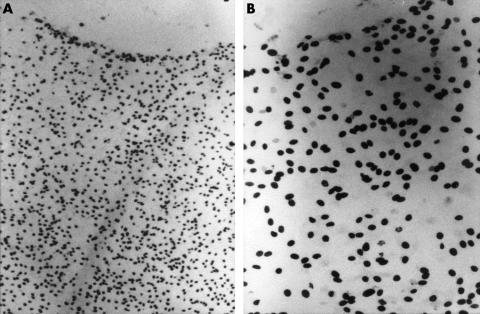

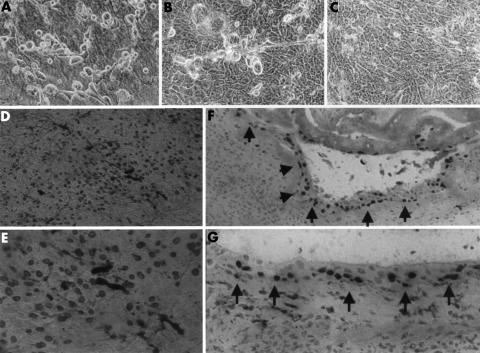

After a continuous labelling for 7 days and a chase for 14 days, HLEC showed a uniformly high labelling index (94.7% (3.5%), n=4) (Fig 6I and 6J). In a separate experiment, we transplanted 6 mm or 7 mm diameter sample of HLEC laden AM, which had been labelled with BrdU for 7 days, onto 3T3 feeder layers. We continued to detect BrdU retaining nuclei after 21 days of chase in this secondary outgrowth (Fig 7). These results showed that HLEC on AM had a number of label retaining cells after prolonged chase, a property further confirming their slow cycling nature. In a subset of experiments, HLEC on AM were treated for 24 hours with 1.0 μg/ml PMA, and labelled continuously with BrdU for 7 days. Phase contrast microscopy revealed that there was increased cellular desquamation after the treatment with PMA (Fig 8A). These changes were observed in some areas leading to a total loss of adherent cells and exposure of the underlying AM stroma, while in other areas adherent cells were less affected. Continuous desquamation was still noted 3 days after treatment (Fig 8B). Remaining adherent cells proliferated to form a cohesive sheet after 7 days (Fig 8C), when they were continuously labelled with BrdU. A high labelling index was noted with BrdU positive cells either as single cells scattered randomly or close to one another in a patch (Fig 8D and 8E), supporting the notion that they were PMA resistant progenitor cells. These cells and AM were transplanted to the subcutaneous space in athymic Balb/c mice and chased for 9 days. The resultant stratified epithelium showed that the majority of label retaining cells were located at the basal layer and some were scattered in the suprabasal cell layers (Fig 8F and 8G). Taken together, these data support the notion that AM cultures preferentially permitted outgrowth from limbal explants, of which the progenitor cells retained the slow cycling property and their proliferative capacity was not inhibited by PMA treatment. After continuous labelling by BrdU, these progenitor cells still retained labels following a prolonged period of chase in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 7.

Label retaining cells after transplantation to 3T3 feeder layers. Secondary outgrowth derived from a 6 mm or 7 mm diameter sample of HLEC laden AM on a 3T3 feeder layer showed numerous label retaining cells after prolonged BrdU labelling for 7 days and 21 days of chase. Magnification: 40× (A); 200× (B).

Figure 8.

Labelling retaining cells after PMA treatment. (A) This phase contrast micrograph reveals increased desquamation leading to denuded AM in some areas of HLEC outgrowth 1 day after PMA treatment. (B) Continuous desquamation was still noted 3 days after PMA treatment. (C) A cohesive monolayer of compact epithelium was noted 7 days after PMA treatment. (D, E) After continuous BrdU labelling for 7 days, a number of cells were labelled on the epithelial sheet. (F, G) After BrdU labelling for 7 days, subsequent implantation into nude mice, and chase for 9 days, the majority of BrdU labelled cells remained in the basal cell layer in the stratified epithelium. Arrows indicate the basally labelled nuclei. Magnification: 80× (D); 100× (F); 200× (A, E, and G); 400× (B, C).

DISCUSSION

In this study we presented a colossus of experimental evidence to support the hypothesis that AM cultures preferentially preserve and expand limbal epithelial SC.

The basal cell layer of HLEC grown on AM was uniformly small, compact, and cuboidal, and had a scanty cytoplasm, poor formation of desmosomal junctions, and rarely developed hemidemosomes (Figs 1 and 2). The expression of cornea specific keratins 3 and 12 was positive on the suprabasal layers. To prove that these basal epithelial cells are indeed undifferentiated, we transplanted the outgrowth together with AM into the subcutaneous environment of nude mice, a manoeuvre previously used to examine SC function of the intestinal epithelial SC40,41 and isolated ocular surface epithelial cells11,42 by promoting proper differentiation. As a result, the transplanted HLEC was markedly stratified and exhibited a phenotype resembling that of the normal limbal epithelium in vivo (Fig 5)—that is, the lack of expression of keratins 3 and 12 in the basal epithelial layer.1,3 These data indicate that the progenitor cells of HLEC are indeed preserved during the expansion by AM cultures.

The outgrowth from limbal explants was preferentially promoted when compared to those derived from the peripheral cornea and central cornea. As a matter of fact, the central cornea did not yield any outgrowth. The lack of supporting progenitor cells from the central cornea was different from those reported using the plastic culture8 or 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers,9 of which both permitted some growth from the human central corneal epithelium. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that AM cultures are more selective for supporting the growth of limbal progenitor cells. Using a similar AM culture, Koizumi et al,43 however, reported that rabbit central corneal explants still generate some outgrowth although to a lesser extent than limbal explants. We attribute such a discrepancy to the difference in the species used because the rabbit central corneal epithelium is known to be more proliferative than the human one.6,14 Taken together, these findings provide additional support for the concept that the limbus contains SC of the corneal epithelium.1

To prove that these ex vivo expanded epithelial progenitor cells possess SC characteristics, we performed cell cycle analysis by BrdU labelling. In vivo, under the normal state the corneal epithelium incorporates pulse administered [3H] thymidine, suggesting that it contains more rapid cycling cells.5,10,44 This notion was also illustrated in this study by a uniformly high labelling index of 61% in the outgrowth of all peripheral corneal explants following 24 hour BrdU labelling. A similar high labelling index was noted in some areas of 35% of the limbal outgrowth tested, suggesting that these limbal explants might have included transient amplifying cells from the peripheral cornea. Alternatively, they might have permitted some differentiation of limbal SC into rapid cycling cells. Notable was the finding that the majority of the limbal explants (65%) showed a low (less than 5%) labelling index, which was increased to 61.5% after a 7 day continuous labelling period. This finding confirmed that the low labelling index noted after 24 hour labelling was indeed the result of slow cycling of the progenitor cells and not a result of post mitotic differentiation. Collectively, these findings indicate that the outgrowth of limbal explants predominantly contains slow cycling progenitor cells, and that 24 hour BrdU labelling is a technique useful to distinguish them from rapid cycling progenitor cells.

After a continuous labelling for 7 days, a large number of the labelled progenitor cells still retained their labels despite 14 or 21 days of chase in the primary culture or following transplantation onto 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers, respectively. The detection of label retaining cells offers another piece of evidence confirming that these progenitor cells are slow cycling in generating their offspring. One might suspect that these slow cycling and label retaining properties of HLEC progenitor cells might be an artefact of AM cultures, which had slowed down cell turnover via differentiation. To rule out this possibility, we briefly exposed them to PMA, a phorbol ester tumour promoter known to cause a divergent response to SC and TAC in epidermal keratinocytes45 46 and ocular surface epithelia.5,7 14 We noted that exposure to PMA for 24 hours increased cell desquamation in some adherent cell layers, indicating the existence of more differentiated TAC, which are known to cease mitosis and undergo terminal differentiation upon exposure to this tumour promoter.7,14,45,46 However, the remaining adherent cells proliferated as evidenced by their continuous growth into a larger epithelial sheet and incorporation of BrdU for 7 days (Fig 8). This experiment proves that AM cultures maintain PMA resistant progenitor cells. Moreover, after subcutaneous transplantation in nude mice, these labelled progenitor cells predominantly remained at the basal level and retained their labels even after 9 days of chase (Fig 8). These findings provide another strong piece of evidence to support the notion that a subpopulation of expanded HLEC are indeed SC, which are known to proliferate and retain labels after treatment with such a tumour promoter.5,7,14

After xenotransplantation to nude mice, the resultant stratified epithelium on AM showed negative staining to K3 keratin in the basal epithelium, and to K12 keratin in both the basal and suprabasal epithelium. The former was identical to what has been reported in the limbal epithelium in vivo, whereas the latter was different. Our preliminary study in rabbits showed that the additional negative staining in the suprabasal epithelium was a result of hyperproliferation in the limbal epithelium. This notion was supported by the finding that the staining for K14 keratin was basal and suprabasal in the resultant epithelium on AM following xenotransplantation while the staining of K14 keratin was only basal in the limbal epithelium in vivo. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism of this different staining pattern.

Previously, epithelial SC have been expanded by co-cultured 3T3 fibroblasts.9,11,13,47–49 Such ex vivo expanded epithelial SC have been used to reconstruct skin following burns50 and in eyes with total limbal SC deficiency.51 The fact that limbal epithelial SC can be preserved and expanded by AM cultures without the inclusion of 3T3 fibroblasts reduces the potential risk of using a mouse derived cell line in human trials. Such ex vivo expanded limbal SC on AM also make it easier to transfer to the recipient eye during surgery. The clinical efficacy of this new approach of transplanting limbal epithelial SC for treating corneal diseases has been reported in a short term study in rabbits31 and clinical patients29,30 with unilateral partial or total limbal SC deficiency. This new approach provides an advantage over the conventional limbal conjunctival autograft52 by reducing the risks to the donor eye inasmuch as a small biopsy of approximately less than 1.5 mm2, but not two large strips of the limbal tissue, will be removed.

In conclusion, strong experimental evidence has been gathered to support the hypothesis that AM cultures preferentially preserve and expand limbal epithelial SC that retain their in vivo characteristics of undifferentiation, slow cycling, label retaining, and resistance to a phorbol ester tumour promoter. Studies to elucidate how such a culture system achieves this novel action may help unravel the secret how the “stemness” of epithelial SC is maintained. This culture system may serve as a first step towards engineering various epithelial tissues and developing new therapeutics targeted at epithelial SC in the future.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Public Health Service research grant No EY 06819 to SCGT from Department of Health and Human Services, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, and in part by a research fellowship grant (Me 1623/1–1) to DM from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn, Germany.

Proprietary interest: SCGT has obtained a patent for the method of preparation and clinical uses of amniotic membrane.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schermer A, Galvin S, Sun T-T. Differentiation-related expression of a major 64K corneal keratin in vivo and in culture suggests limbal location of corneal epithelial stem cells. J Cell Biol 1986;103:49–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tseng SCG. Regulation and clinical implications of corneal epithelial stem cells. Mol Biol Rep 1996;23:47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen WYW, Mui M-M, Kao WW-Y, et al. Conjunctival epithelial cells do not transdifferentiate in organotypic cultures: expression of K12 keratin is restricted to corneal epithelium. Curr Eye Res 1994;13: 765–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C-Y, Zhu G, Converse R, et al. Characterization and chromosomal localization of the cornea-specific murine keratin gene Krt1.12. J Biol Chem 1994;260:24627–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotsarelis G, Cheng SZ, Dong G, et al. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell 1989;57:201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng SCG, Zhang S-H. Limbal epithelium is more resistant to 5-fluorouracil toxicity than corneal epithelium. Cornea 1995;14: 394–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavker RM, Wei ZG, Sun TT. Phorbol ester preferentially stimulates mouse fornical conjunctival and limbal epithelial cells to proliferate in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998;39:301–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebato B, Friend J, Thoft RA. Comparison of central and peripheral human corneal epithelium in tissue culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1987;28:1450–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindberg K, Brown ME, Chaves HV, et al. In vitro preparation of human ocular surface epithelial cells for transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993;34:2672–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavker RM, Dong G, Cheng SZ, et al. Relative proliferative rates of limbal and corneal epithelia. Implications of corneal epithelial migration, circadian rhythm, and suprabasally located DNA-synthesizing keratinocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1991;32:1864–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Z-G, Lin T, Sun T-T, et al. Clonal analysis of the in vivo differentiation potential of keratinocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997;38:753–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng SCG, Kruse FE, Merritt J, et al. Comparison between serum-free and fibroblast-cocultured single-cell clonal culture systems: evidence showing that epithelial anti-apoptotic activity is present in 3T3 fibroblast conditioned media. Curr Eye Res 1996;15:973–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellegrini G, Golisano O, Paterna P, et al. Location and clonal analysis of stem cells and their differentiated progeny in the human ocular surface. J Cell Biol 1999;145:769–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruse FE, Tseng SCG. A tumor promoter-resistant subpopulation of progenitor cells is present in limbal epithelium more than corneal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993; 34:2501–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JJY, Tseng SCG. Corneal epithelial wound healing in partial limbal deficiency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1990;31:1301–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JJY, Tseng SCG. Abnormal corneal epithelial wound healing in partial thickness removal of limbal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1991;32:2219–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang AJW, Tseng SCG. Corneal epithelial wound healing in the absence of limbal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1991;32:96–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruse FE, Chen JJY, Tsai RJF, et al. Conjunctival transdifferentiation is due to the incomplete removal of limbal basal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1990;31:1903–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puangsricharern V, Tseng SCG. Cytologic evidence of corneal diseases with limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology 1995;102:1476–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng SCG, Sun T-T. In: Brightbill FS, ed. Corneal surgery: theory, technique, and tissue. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby, 1999:9–18.

- 21.Tseng SCG. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, eds. Duane's clinical ophthalmology. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1994:1–11.

- 22.Holland EJ, Schwartz GS. The evolution of epithelial transplantation for severe ocular surface disease and a proposed classification system. Cornea 1996;15:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JC, Tseng SCG. Transplantation of preserved human amniotic membrane for surface reconstruction in severely damaged rabbit corneas. Cornea 1995;14:473–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsubota K, Satake Y, Ohyama M, et al. Surgical reconstruction of the ocular surface in advanced ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1996;122:38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimazaki J, Yang H-Y, Tsubota K. Amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction in patients with chemical and thermal burns. Ophthalmology 1997;104:2068–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tseng SCG, Prabhasawat P, Barton K, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation with or without limbal allografts for corneal surface reconstruction in patients with limbal stem cell deficiency. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsubota K, Satake Y, Kaido M, et al. Treatment of severe ocular surface disorders with corneal epithelial stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson DF, Ellies P, Pires RTF, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for partial limbal stem cell deficiency: long term outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:567–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai RJF, Li L-M, Chen J-K. Reconstruction of damaged corneas by transplantation of autologous limbal epithelial cells. N Engl J Med 2000;343:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwab IR, Reyes M, Isseroff RR. Successful transplantation of bioengineered tissue replacements in patients with ocular surface disease. Cornea 2000;19:421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koizumi N, Inatomi T, Quantock AJ, et al. Amniotic membrane as a substrate for cultivating limbal corneal epithelial cells for autologous transplantation in rabbits. Cornea 2000;19:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inatomi T, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, et al. Expression of secretory mucin genes by human conjunctival epithelia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:1684–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bara J, Gautier R, Mouradian P, et al. Oncofetal mucin M1 epitope family: characterization and expression during colonic carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer 1991;47:304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang AJW, Tseng SCG. Development of monoclonal antibodies to rabbit ocular mucin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1987;28:1483–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meller D, Tseng SCG. Conjunctival epithelial cell differentiation on amniotic membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999;40:878–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jumblatt JE, Neufeld AH. Beta-adrenergic and serotonergic responsiveness of rabbit corneal epithelial cells in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1983;24:1139–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maki T, Gottschalk R, Wood ML, et al. Specific unresponsiveness to skin allografts in anti-lymphocyte serum treated, marrow-injected mice: Participation of donor marrow-derived suppressor T cells. J Immunol 1981;127:1433–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gray JG, Monaco AP, Wood ML, et al. Studies on heterologous anti-lymphocyte serum in mice. J Immunol 1966;96:217–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood ML, Monaco AP, Gozzo J, et al. Use of homozygous allogeneic bone marrow for induction of tolerance with anti-lymphocyte serum: dose and timing. Transplant Proc 1971;3:676–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booth C, O'Shea JA, Potten CS. Maintenance of functional stem cells in isolated and cultured adult intestinal epithelium. Exp Cell Res 1999;249:359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kedinger M, Simon-Assmann PM, Lacroix B, et al. Fetal gut mesenchyme induces differentiation of cultured intestinal endodermal and crypt cells. Dev Biol 198;113:474–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei Z-G, Sun T-T, Lavker RM. Rabbit conjunctival and corneal epithelial cells belong to two separate lineages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:523–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koizumi N, Fullwood NJ, Bairaktaris G, et al. Cultivation of corneal epithelial cells on intact and denuded human amniotic membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000;41:2506–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haddad A. Renewal of the rabbit corneal epithelium as investigated by autoradiography after intravitreal injection of 3H-thymidine. Cornea 2000;19:378–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuspa SH, Ben T, Hennings H, et al. Divergent responses in epidermal basal cells exposed to the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecacanoylphorboAB-13-acetate. Cancer Res 1982;42:2344–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furstenberger G, Gross M, Schweizer J, et al. Isolation, characterization and in vitro cultivation of subfractions of neonatal mouse keratinocytes: effects of phorbolesters. Carcinogenesis 1986;7: 1745–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rheinwald JG, Green H. Serial cultivation of strains of human epidermal keratinocytes: the formation of keratinizing colonies from single cells. Cell 1975;6:331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrandon Y, Green H. Three clonal types of keratinocytes with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987;84:2302–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobayashi K, Rochat A, Barrandon Y. Segregation of keratinocyte colony-forming cells in the bulge of the vibrissa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:7391–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Green H, Kehinde O, Thomas J. Growth of cultured human epidermal cells into multiple epithelia suitable for grafting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1979;76:5665–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pellegrini G, Traverso CE, Franzi AT, et al. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surface with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet 1997;349:990–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kenyon KR, Tseng SCG. Limbal autograft transplantation for ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology 1989;96:709–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]