Commotio retinae results in retinal opacification following blunt trauma. Mild commotio retinae usually settles spontaneously with minimal sequelae but more severe cases are associated with visual loss. We are not aware of any previous reports describing optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging of severe commotio retinae with an associated full thickness macular hole (FTMH).

Case report

A 15 year old boy presented 24 hours after blunt trauma from a football striking his right eye. On examination his best corrected visual acuity was counting fingers right eye and 6/6 left. Biomicroscopic examination revealed extensive commotio retinae over the posterior pole, no posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), and a FTMH. Colour photography and OCT imaging (OCT 2000 scanner, Zeiss-Humphrey) were performed (Fig 1). OCT confirms a FTMH and demonstrates extensive disruption of photoreceptor outer segments and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

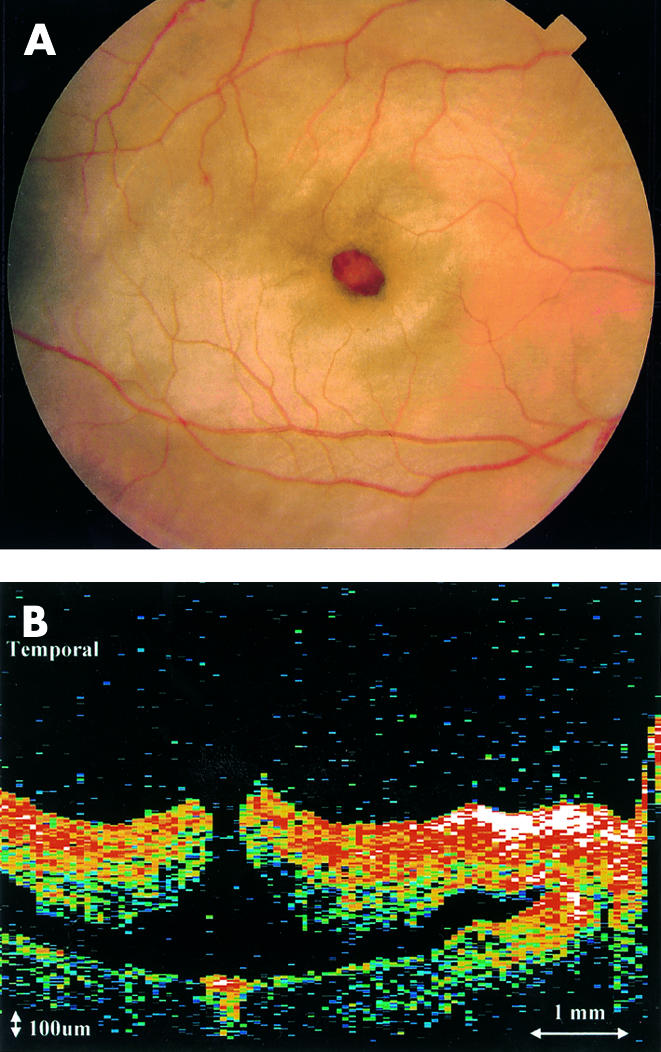

Figure 1.

(A) Right macula of 15 year old boy with extensive commotio retinae over posterior pole and an associated macular hole at 1 day after blunt injury. (B) Horizontal OCT scan through centre of macula confirms a full thickness macular hole and demonstrates extensive disruption of photoreceptor outer segment/retinal pigment epithelium layer. The optic disc is seen at the nasal edge of the scan.

He was treated conservatively with a short course of topical steroids. The colour fundus and OCT appearance at 1 month are shown in Figure 2. Despite spontaneous macular hole closure, visual acuity remained at counting fingers at 1 year follow up.

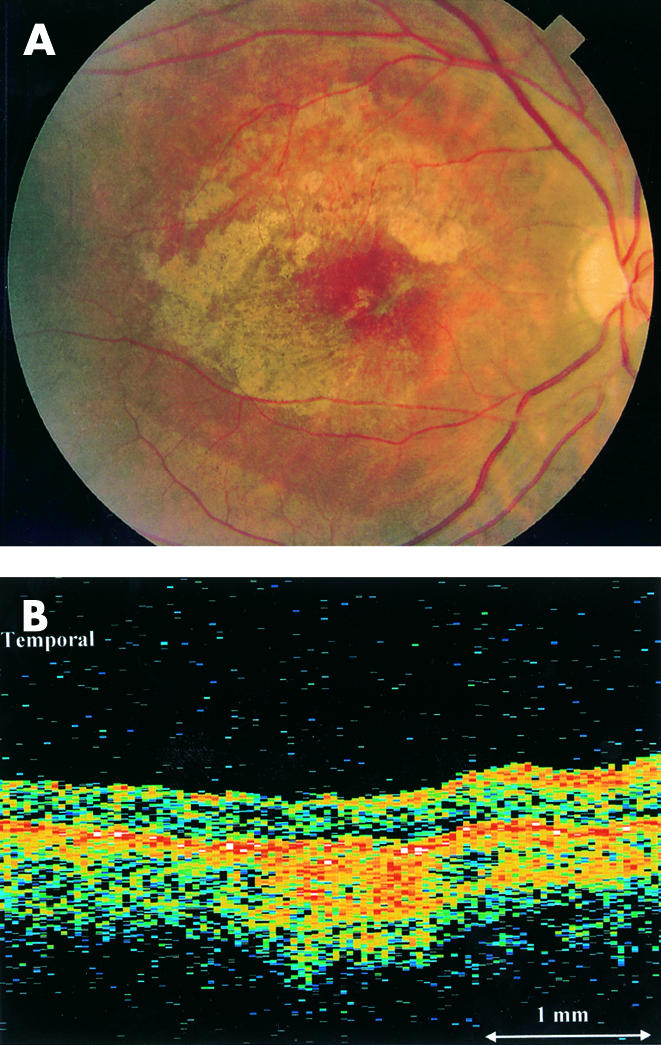

Figure 2.

(A) Right macula 1 month after injury with extensive retinal pigment epithelium disruption, marked epiretinal membrane, and spontaneous closure of the macular hole. (B) Horizontal OCT scan through centre of right macular confirms resolution of commotio retinae, spontaneous closure of macular hole, and disruption of the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium reflex.

Comment

The major site of retinal trauma appeared on OCT to be at the level of the photoreceptor outer segment/RPE interface. The OCT images are consistent with fragmentation of photoreceptor outer segments and damaged cell bodies, as suggested by Sipperley et al1 in their study of the histological changes in commotio retinae in primates.

The exact pathogenesis of macular holes remains uncertain. Ho et al2 outlined the three basic historical theories regarding aetiology—the traumatic theory, the cystic degeneration and vascular theory, and the vitreous theory. Of these, the latter has gathered the most support in the context of idiopathic macular holes.

In our case, the OCT imaging reveals that the edges of the macular hole are elliptical and irregular with no associated PVD, cortical vitreous condensation, or overlying prefoveal opacity. The characteristics suggest a different mechanism of hole formation from that proposed in idiopathic senile macular holes. We believe that mechanical distortion of the retina, relative to the vitreous and underlying sclera, created disruption of the photoreceptor outer segments and creation of a FTMH in this case. It is at the fovea and photoreceptor outer segment level that the retina has the least support from Müller cells and is therefore likely to undergo greatest deformation.

In the only previous report of OCT imaging in traumatic macular hole, a case with mild commotio retinae was described in which extensive outer retinal disruption was not observed.3 There have been some encouraging reports suggesting that vitrectomy can successfully close traumatic macular holes as well as improve visual function in many cases.4, 5 However, it seems unlikely that cases with severe commotio retinae, and associated photoreceptor/RPE damage, as demonstrated in our cases, would gain any benefit from surgical as opposed to spontaneous closure of a traumatic FTMH. The final visual prognosis is severely limited by the extent of initial photoreceptor damage, and the excessive pigment atrophy and clumping that follows.

We believe OCT imaging provides additional information both on the pathogenesis of commotio retinae and in the assessment of outer retina disruption following ocular trauma. This information may help in the selection of patients likely to benefit from surgical intervention.

References

- 1.Sipperley JO, Quigley HA, Gass DM. Traumatic retinopathy in primates. The explanation of commotio retinae. Arch Ophthalmol 1978;96:2267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho AC, Guyer DR, Fine SL. Macular hole. Surv Ophthalmol 1998;42:393–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parmar DN, Stanga PE, Reck AC, et al. Imaging of a traumatic macular hole with spontaneous closure. Retina 1999;19:470–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amari F, Ogino N, Matsumura M, et al. Vitreous surgery for traumatic macular holes. Retina 1999;19:410–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson RN, McDonald R, Lewis H, et al. Traumatic macular hole. Observations, pathogenesis, and results of vitrectomy surgery. Ophthalmology 2001;108:853–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]