Abstract

Aims: To study the ocular manifestations and their severity in children with Graves' disease.

Methods: All patients with Graves' disease having regular follow up in a paediatric endocrine clinic were recruited for the study. A comprehensive ophthalmic assessment including ocular motility, exophthalmometry, intraocular pressure (IOP), slit lamp, and fundus examinations was performed.

Results: 83 patients (72 female, 11 male) aged 16 years or below were examined. All are Chinese. Ocular symptoms occurred in 12 patients. Ocular signs of ophthalmopathy were documented in 52 patients (62.7%). Most of them presented with eyelid abnormalities such as lid oedema, lid lag, and lagophthalmos, whereas lower lid retraction was the commonest clinical sign noted (38.6%). Diffuse conjunctival injection was found in four patients (4.8%). 10 patients (12.0%) had mild proptosis of less than 3 mm. Only one patient (1.2%) had limited extraocular motility in extreme gaze. Punctate epithelial corneal erosions were reported in 11 patients (13.3%).

Conclusions: This is the largest series on the ocular complications of childhood Graves' disease in the literature. Although 52 patients (62.7%) were identified with positive ocular changes, none of them had visual threatening complications or debilitating myopathy.

Keywords: Graves' ophthalmopathy, ocular complications, children

The ocular changes associated with thyroid dysfunction have been recognised for more than 150 years, yet controversy still remains regarding the pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and management of this disease.1–3 A combination of more laboratory and clinical studies is essential to improve the understanding of this complex disease.

Graves' ophthalmopathy is an organ specific autoimmune process strongly linked to Graves' hyperthyroidism.4 Although the hyperthyroidism can be successfully treated, it is often the ophthalmopathy that produces the greatest long term disability in patients with this disease.5 Eyelid retraction, proptosis, periorbital oedema, chemosis, and disturbances of ocular motility can lead to both cosmetic and functional sequelae. In some cases, the disease may progress to visual loss as a result of exposure to keratopathy or compressive optic neuropathy.6

The information on Graves' ophthalmopathy is less well established in children than in adults. Most of the serious conditions described in the adult series7–9 were only occasionally reported in the paediatric age group.10–12 There have been a few series of paediatric cases of Graves' disease in the literature describing the eye manifestations.12–14 However, the number of cases in these studies were relatively small, ranging from eight to 43, and they were mainly in white patients.

In our study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence and severity of ophthalmopathy in a larger group of Graves' patients with onset of disease younger than 16 years. In addition, we compared and contrasted the clinical presentations in Chinese patients with those of previously reported studies.

PATIENTS

This was a cross sectional study. All patients with confirmed diagnosis of Graves' disease and with regular follow up in the paediatric endocrine clinic of the Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong in 1998 were recruited to the study. The diagnosis of Graves' disease was based on clinical and laboratory findings of diffused enlargement of thyroid gland, raised free thyroxine or tri-iodothyronine levels, suppressed thyroid stimulating hormone levels, and the presence of thyroid receptor antibodies measured by a radioreceptor method (RSR Limited, UK).15 All patients and the parents of the patients were informed of the study and written consent was obtained. Information regarding ocular symptoms, family history, smoking history, and associated systemic disease was also obtained in the same setting. The records of the patients were reviewed to evaluate the recent thyroid disease status and the treatment regimen. All patients were clinically euthyroid at the time of their ocular examinations.

METHODS

Standardised examination

The comprehensive ophthalmic examination was performed in a standardised way for all patients. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was documented by Snellen chart. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured in primary position and upward gaze. Eyelid, conjunctiva and ocular motility status were assessed. Retraction of either upper or lower eyelid was defined as any exposed superior or inferior sclera beyond the limbus in the primary gaze. Degree of proptosis was measured by the Hertel exophthalmometer. Proptosis was defined as the measurement of anteroposterior protrusion of the globe >19 mm from the orbital rim in either eye or any discrepancy in the degree of protrusion of the two eyes by >1 mm.16 Corneal involvement was assessed with fluorescein staining under slit lamp microscopy. The relation of their thyroid functions and ocular manifestations were also evaluated.

RESULTS

A total of 83 paediatric patients with the systemic Graves' disease were studied. There were 72 females and 11 males. The median age of onset of Graves' disease was 11 years (mean 9.5 (SD 4.8) years). At the time of their ocular examinations, the subjects had been followed up at the paediatric endocrine clinic for a median duration of 45 months (mean 51.3 (29) months). Although 15 patients (18.1%) had more than one relapse, most of them (68 patients, 81.9%) were either in remission or receiving their first course of oral treatment at the time of assessment. Both active and chronic disease states were present in the group. Fifty four patients (65.1%) were still taking medical treatment while 29 (34.9%) were in remission. Among the subjects, family history (mother, father, or siblings) of thyrotoxicosis was positive in 16 (19.3%) subjects; 79 patients (95.2%) were non-smokers, three patients (3.6%) were smokers, and one patient (1.2%) was an ex-smoker. On the other hand, 41 patients (49.4%) had household members who smoked currently. None of the patients had associated systemic disease, such as thyroid dermopathy, acropachy, myasthenia gravis, or diabetes mellitus.

All patients were treated with oral antithyroid medication only and none received radioactive iodine treatment.

Among the 83 patients, 12 (14.5%) reported ocular symptoms. These included pain, foreign body sensation, photosensitivity, epiphora, and diplopia. Most of the patients had eyelid signs, four patients (4.8%) had upper lid retraction, 32 (38.6%) had lower lid retraction, five (6.0%) had lid oedema, and five (6.0%) had lid lag. Lagophthalmos was found in eight patients (9.6%) while diffuse conjunctival injection was present in four patients (4.8%). Ten patients (12.0%) were detected to have mild proptosis. When comparing the IOP measured in upgaze and primary gaze, six patients (7.2%) had higher measurement in upgaze position by 3 mm Hg or more. Only one patient (1.2%) had limited extraocular motility in extreme gaze. On the other hand, 11 patients (13.3%) stained positive with fluorescein in their corneas. Clinically, all of them had punctate epithelial erosions; no superior limbic keratitis or corneal ulceration was detected. None of the patients was found to have visual impairment or optic nerve dysfunction.

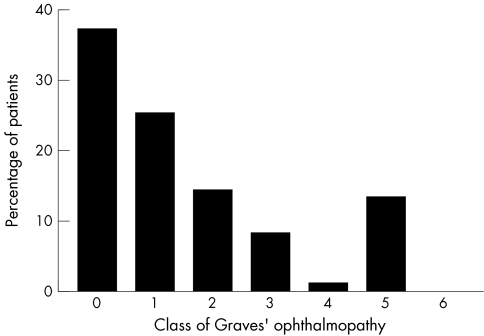

In categorising the ocular manifestations of Graves' diseases with an abridged NOSPEC classification into classes 0 to 6, 31 patients (37.3%) would be in class 0, 21 (25.3%) in class 1, 12 (14.5%) in class 2, seven (8.4%) in class 3, one (1.2%) in class 4, 11 (13.3%) in class 5, and 0 in class 6 (Fig 1).17

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of severity according to the abridged classification of eye changes in Graves' disease.

In defining the risk factors, we could not find any positive correlation between the ophthalmic manifestations with disease status, family history of Graves' disease, or smoking.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of Graves' disease in adults has been reported to be between 15–20 per 100 000 per year.15 Graves' disease in children, however, has been reported to be rare and the calculated incidence was only 0.79 per 100 000 in Danish children.18 On the other hand, a recent study in Hong Kong Chinese has documented an incidence of 6.5 per 100 000 children.19 Marked differences exist between adults and children as well as Chinese and other ethnic groups in Graves' disease.

Similarly, Graves' ophthalmopathy also behaves differently in different age and ethnic groups. Bartley et al reported the ophthalmic manifestations and complications in an adult series of 120 patients with Graves' disease, the frequency of exophthalmos could be as high as 60.8% (73 out of 120 patients), restrictive extraocular myopathy 42.5% (51 patients), and optic nerve dysfunction 5.8% (seven patients).7 In our study only 12.0% (10 patients) had exophthalmos, 1.2% (one patient) had mild restrictive myopathy, and no patient had optic nerve dysfunction. Previous studies on dysthyroid ophthalmopathy in children also suggested that the degree of ophthalmopathy appears to be substantially more benign than that found in adults.12,14 The low frequency of extraocular myopathy in the paediatric group remains unknown. It is postulated to be related to the lower levels of thyroid antibody.13 One of the diagnostic parameters for thyroid myopathy is the IOP elevation on upward gaze. In this study, six out of 83 subjects had more than 3 mm Hg difference. This seems to be in contrast with the very low frequency of mild restrictive myopathy (one out of 83). However, the utility of IOP change on upgaze in clinical practice remains controversial.20–22 In Reader's study on 100 healthy eyes, the mean increase in IOP at 20 degree upgaze was 1.75 (SD 1.49) mm Hg. Five subjects had an increase in IOP of 4 mm Hg and one subject had a 6 mm Hg increase.23 Therefore, the pressure elevation has to be interpreted very carefully.

According to the international abridged classification of the eye changes of Graves' disease (Table 1),17 we grouped our patients into classes 0 to 6 and compared them with similar studies (Table 2). Among the four studies, ours has the largest number of patients.12–14 The proportion of patients with positive ocular manifestations was the highest in this cohort (62.7% in the current study). Eyelid signs were the predominant complication in all studies. Symptomatic conditions and soft tissue involvement occurred in about 10–15% of all patients. Exophthalmos did present in this age group but was uncommon. In Liu's series,11 all the children had prominent proptosis and were associated with a hyperthyroid state. In contrast, some of our patients were found to have mild proptosis despite being euthyroid. More importantly, 11 patients were found to have corneal complications in the current study but none in the other studies. Nevertheless, all of them only had mild punctate epithelial erosions rather than any vision threatening corneal condition. This might be related to the high incidence of lower lid retraction and lagophthalmos as the lesions were located at the inferior periphery of the cornea. The punctate epithelial erosions in the cornea can be managed with lubricating eye drops; however, the treatment may need to be continued even if the Graves' disease is in remission.

Table 1.

Abridged classification of eye changes of Graves' disease

| Class | Definition |

| 0 | No physical signs or symptoms |

| 1 | Only signs, no symptoms (signs limited to upper eyelid retraction, stare, and eyelid lag) |

| 2 | Soft tissue involvement (symptoms and signs) |

| 3 | Proptosis |

| 4 | Extraocular muscle involvement |

| 5 | Corneal involvement |

| 6 | Sight loss (optic nerve involvement) |

Table 2.

Severity of Graves' ophthalmopathy in different studies

| Uretsky13 | Young14 | Gruters15 | Present study | |

| Age of onset (range in years) | 1–17 | 5–20 | Not mentioned | 2–16 |

| Number of cases | 23 | 33 | 43 | 83 |

| Abridged classification | ||||

| Class 0 | 11 (47.8%) | 17 (51.5%) | 24 (55.8%) | 31 (37.3%) |

| Class 1 | 8 (34.8%) | 12 (36.4%) | 16 (37.2%) | 24 (28.9%) |

| Class 1 | 8 (34.8%) | 12 (36.4%) | 16 (37.2%) | 19 (22.9%) |

| Class 2 | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (9.1%) | 0 | 12 (14.5%) |

| Class 3 | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (3.0%) | 3 (7.0%) | 4 (4.8%) |

| Class 3 | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (3.0%) | 3 (7.0%) | 7 (8.4%) |

| Class 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2%) |

| Class 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (13.3%) |

| Class 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Graves' disease clusters in families but the importance of heredity in the pathogenesis of the associated ophthalmopathy is unclear. In the present study, 16 patients (19.3%) had a positive family history of Graves' disease. We did not examine the family members of patients to document the family history of Graves' ophthalmopathy for further correlation. From the literature, Villanueva24 had studied the family history of 114 consecutive, ethnically mixed patients with severe Graves' ophthalmopathy. Only three of the 114 patients had a family history of severe Graves' ophthalmopathy, which were all in second degree relatives. His data did not support a major role for familial factors in the development of severe Graves' ophthalmopathy.

Various studies25,26 suggested that other factors, rather than major genes, were likely to predispose certain individuals to severe Graves' ophthalmopathy. Smoking and radioactive iodine treatment have been implicated in the manifestations of thyroid ophthalmopathy.19 Mann27 reported a sevenfold increase in risk of thyroid associated orbitopathy, and the number of cigarettes smoked per day appeared to be a significant independent determinant for the incidence of proptosis and diplopia. We also included the patients' smoking history and environment with cigarette smoking in our study. Both the number with proptosis and smokers in the current study were small such that a definitive conclusion regarding the relation of active or passive smoking and childhood thyroid eye disease cannot be made from this study. Radioiodine treatment was not a factor contributing to the development of ophthalmopathy in our subjects as none received such treatment.

In conclusion, ocular manifestations are common in paediatric Graves' disease. However, they are much milder than in adult Graves' ophthalmopathy. Among the 52 patients (62.7%) with positive ocular changes, none of them had visual threatening complications or debilitating myopathy. Most of the patients only required treatment with lubricating eye drops.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Supported in part by the Action for Vision Eye Foundation, Hong Kong.

Proprietary interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waldhausen JH. Controversies related to the medical and surgical management of hyperthyroidism in children. Semin Pediatr Surg 1997;6:121–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrie WE. Graves' ophthalmopathy. West J Med 1993;158:591–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glaser NS, Styne DM. Predictors of early remission of hyperthyroidism in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:1719–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahn RS, Dutton CM, Natt N, et al. Thyrotropin receptor expression in Graves' orbital adipose/connective tissues: potential autoantigen in Graves' ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:998–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter JA, Utiger RD. The ophthalmopathy of Graves' disease. Annu Rev Med 1992;43:487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeatts RP. Graves' ophthalmopathy. Med Clin North Am 1995;79:195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartley GB, Fatourechi V, Kadrmas EF, et al. Clinical features of Graves' ophthalmopathy in an incidence cohort. Am J Ophthalmol 1996;121:284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadrmas EF, Bartley GB. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. A prognostic sign for severe Graves' ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmology 1995;102:1472–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Char DH. The ophthalmopathy of Graves' disease. Med Clin North Am 1991;75:97–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metz HS, Woolf PD, Patton ML. Endocrine ophthalmomyopathy in adolescence. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1982;19:58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu GT, Heher KL, Katowitz JA, et al. Prominent proptosis in childhood thyroid eye disease. Ophthalmology 1996;103:779–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uretsky SH, Kennerdell JS, Gutai JP. Graves' ophthalmopathy in childhood and adolescence. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:1963–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young LA. Dysthyroid ophthalmopathy in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1979;16:105–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruters A. Ocular manifestations in children and adolescents with thyrotoxicosis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 1999;107(Suppl 5):S172–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker DJ, Phillips DI. Current incidence of thyrotoxicosis and past prevalence of goitre in 12 British towns. Lancet 1984;2:567–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quant JR, Woo GC. Normal values of eye position and head size in Chinese children from Hong Kong. Optom Vis Sci 1993;70:668–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartley GB. Evolution of classification systems for Graves' ophthalmopathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;11:229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perrild H, Lavard L, Brock-Jacobsen B. Clinical aspects and treatment of juvenile Graves' disease. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 1997;105(Suppl 4):55–7:55–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong GW, Cheng PS. Increasing incidence of childhood Graves' disease in Hong Kong: a follow-up study. Clin Endocrinol 2001;54:547–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamblin GT, Harper DG, Galentine P, et al. Prevalence of increased intraocular pressure in Graves' disease–evidence of frequent subclinical ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 1983;308:420–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen C, Stetz D, Roman SH, et al. Prevalence and clinical associations of intraocular pressure changes in Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1985;61:183–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spierer A, Eisenstein Z. The role of increased intraocular pressure on upgaze in the assessment of Graves ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmology 1991;98:1491–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reader AL III. Normal variations of intraocular pressure on vertical gaze. Ophthalmology 1982;89:1084–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villanueva R, Inzerillo AM, Tomer Y, et al. Limited genetic susceptibility to severe Graves' ophthalmopathy: no role for CTLA-4 but evidence for an environmental etiology. Thyroid 2000;10:791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winsa B, Mandahl A, Karlsson FA. Graves' disease, endocrine ophthalmopathy and smoking. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1993;128:156–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tallstedt L, Lundell G, Taube A. Graves' ophthalmopathy and tobacco smoking. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1993;129:147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann K. Risk of smoking in thyroid-associated orbitopathy. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 1999;107(Suppl 5):S164–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]