Abstract

Aim: To examine the relation between blood pressure and retinal microvascular abnormalities in older people.

Methods: The Cardiovascular Health Study is a prospective cohort study conducted in four US communities initiated in 1989 to 1990. Blood pressure was measured according to standardised protocols at each examination. During the 1997–8 examination, retinal photographs were taken of 2405 people aged 69–97 years (2056 without diabetes and 349 with diabetes). Signs of focal microvascular abnormalities (focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, and retinopathy) were evaluated from photographs according to standardised methods. To quantify generalised arteriolar narrowing, the photographs were digitised and diameters of individual arterioles were measured and summarised.

Results: In non-diabetic people, elevated concurrent blood pressure taken at the time of retinal photography was strongly associated with presence of all retinal microvascular lesions. The multivariable adjusted odds ratios, comparing the highest to lowest quintile of concurrent systolic blood pressure, were 4.0 (95% confidence intervals (CI): 2.4 to 6.9, p test of trend<0.001) for focal arteriolar narrowing, 2.9 (95% CI: 1.6 to 5.3, p<0.001) for arteriovenous nicking, 2.8 (95% CI: 1.5 to 5.2, p<0.001) for retinopathy, and 2.1 (95% CI: 1.4 to 3.1, p<0.001) for generalised arteriolar narrowing. Generalised arteriolar narrowing and possibly arteriovenous nicking were also significantly associated with past blood pressure measured up to 8 years before retinal photography, even after adjustment for concurrent blood pressure. These associations were somewhat weaker in people with diabetes.

Conclusions: Retinal microvascular abnormalities are related to elevated concurrent blood pressure in older people. Additionally, generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing and possibly arteriovenous nicking are related to previously elevated blood pressure, independent of concurrent blood pressure. These data suggest that retinal microvascular changes reflect severity and duration of hypertension.

Keywords: retinal microvascular disease, hypertensive retinopathy, retinal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, blood pressure

Retinal microvascular abnormalities, such as focal and generalised arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, and retinopathy (for example, microaneurysms and retinal haemorrhages) are seen fairly frequently in the adult population.1 Although these retinal abnormalities are long known to be associated with hypertension status and elevated blood pressure (BP),2–9 much remains to be understood regarding the nature of these associations. Studies have shown that retinal microvascular abnormalities can be detected even in people without a history of hypertension or diabetes,1,7 and predict incident stroke independent of measured BP levels.10 Thus, it has been suggested that some of these retinal lesions do not simply reflect current BP levels but are markers of persistent microvascular damage from hypertension.11

This hypothesis is supported by data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a large population based study of cardiovascular disease in middle aged people. The ARIC study demonstrated that generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing and arteriovenous nicking, as ascertained from retinal photographs, were strongly related not only to BP measured at the time of photography, but also independently to past BP measured 3–6 years before the photography.12 Few other population based data regarding such associations are available, particularly in older people.

The aim of this study is to examine the relation of hypertension status and concurrent and past BP to retinal microvascular abnormalities in older men and women aged 69–97 years.

METHODS

Study population

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a population based cohort study of cardiovascular disease in adults 65 years of age and older.13 The study population and conduct are described in detail elsewhere.14 In brief, recruitment of the original cohort of 5201 people took place in 1989 to 1990 in four field centres: Allegheny County, PA, USA; Forsyth County, NC, USA; Sacramento County, CA, USA; and Washington County, MD, USA. An additional 687 eligible black people were recruited from Forsyth County, Sacramento County, and Allegheny County in 1992–3. Differences between those recruited and those not recruited have been presented elsewhere.14

Retinal photographs were offered to participants who returned for the clinic examination in 1997–8, approximately 8 years after the baseline examination. Of 4249 people (95.5% of survivors) who were contacted at this examination, we initially excluded 247 people with missing data for a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (because diabetes status may complicate the understanding of the association between BP and retinal microvascular signs). Of the remaining 4002 people, 3002 were examined at the study clinics and the other 1000 were examined at home or in nursing institutions or were contacted only by mail/phone. Retinal photographs were available for 2793 people (2754 were those examined at the study clinics), but could not be graded for any retinal microvascular signs in 388 people because of poor quality due to media opacities or small pupil size. Thus, 2405 people with gradable retinal photographs were available for this study. Of these, 2056 did not have diabetes and 349 had diabetes, as defined according to the American Diabetes Association criteria15 (treatment with either oral hypoglycaemic agents and/or insulin in the year before the examination; or having a fasting blood sugar of ≥126 mg/dl for those not using any hypoglycaemic agents in the past year).

Comparisons of people with (n = 2405) and without (n = 1597) retinal photographs or gradable photographs appear in Table 1. Not having photographs or gradable photographs was associated with increasing age, female sex, and black ethnicity. After controlling for age, sex, and race, those excluded had a significantly higher diastolic BP and fasting glucose and were more likely to have a history of coronary heart disease and stroke and to consume less alcohol.

Table 1.

Comparison of people included and excluded who attended the 1997–8 cardiovascular health study examination

| Adjusted means or percentage* | |||

| Included (n=2405) | Excluded (n=1597) | p Value† | |

| Age (years) | 78.3 | 80.7 | <0.001 |

| Women (%) | 60.0 | 63.6 | 0.024 |

| Black (%) | 14.6 | 21.9 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 59.2 | 57.5 | 0.394 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 132.0 | 132.9 | 0.297 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 66.5 | 67.6 | 0.010 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 101.8 | 104.4 | 0.038 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 24.7 | 30.9 | <0.001 |

| Stroke (%) | 6.2 | 11.5 | <0.001 |

| Cigarette smoking, current (%) | 6.3 | 8.0 | 0.059 |

| Alcohol consumption, current (%) | 41.4 | 26.8 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 202.4 | 201.7 | 0.641 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, and race (except for age, men and black, which are unadjusted for age, sex, and race, respectively).

†p Value represents difference in adjusted means or proportions between included and excluded.

Retinal photography and grading

Retinal photography procedures in the CHS were similar to the ARIC study, which have been previously reported in detail.16 Briefly, photographs of the retina were taken of one randomly selected eye after 5 minutes of dark adaptation and evaluated according to standardised protocols at the Fundus Photograph Reading Center, University of Madison, WI, USA by trained graders who were masked to subject identity.

Focal microvascular lesions were evaluated from the photographic slides using standardised methods.16 Focal arteriolar narrowing and arteriovenous nicking were defined as present if graded definite or probable. Retinopathy was defined as present if any of the following lesions were graded definite or probable: microaneurysms, retinal haemorrhages (blot or flame-shaped), soft exudates (cotton wool spots), hard exudates, macular oedema, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, venous beading, new vessels at the disc or elsewhere, vitreous haemorrhage, disc swelling, and laser photocoagulation scars.

For the evaluation of generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing, the photographic slides were digitised with a high resolution scanner. The diameters of all arterioles and venules coursing through a specified area half to one disc diameter from the optic disc were measured on the computer.16 The individual arteriolar and venular diameters were combined into summary measures (referred to as arteriolar and venular equivalents) using formulas by Parr17,18 and Hubbard.16 The arteriolar and venular equivalents have an approximately normal distribution, with smaller equivalents representing narrower average arteriolar and venular diameters in that eye, respectively.16

Quality control procedures were implemented during the “light box” and computer assisted grading. In the CHS, there were 71 intragrader and 69 intergrader re-readings. The intragrader kappa statistics were 0.57 for focal arteriolar narrowing, 0.49 for arteriovenous nicking, and 0.90 for retinopathy, while the intergrader kappa statistics were 0.31, 0.43, and 0.88 for the corresponding retinal lesions. For arteriolar and venular equivalents, the intragrader and intergrader intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.67 to 0.91.

Definition of hypertension status, and concurrent and past blood pressure

BP was measured annually using standardised written protocols over the study duration of 9 years (1989–98).19 Hypertension status was defined at the time of retinal photography (1997–8 examination). A person was considered to have hypertension based on systolic BP 140 mm Hg or greater, diastolic BP 90 mm Hg or greater, or the combination of self reported high BP diagnosis and use of antihypertensive medications. A person with hypertension was further classified into mutually exclusive categories: (1) treated, controlled hypertension (using antihypertensive medications, systolic BP less than 140 mm Hg, and diastolic BP less than 90 mm Hg), (2) treated, uncontrolled hypertension (using antihypertensive medications and systolic BP 140 mm Hg or greater, or diastolic BP 90 mm Hg or greater), and (3) untreated hypertension (not using antihypertensive medications and systolic BP 140 mm Hg or greater, or diastolic BP 90 mm Hg or greater).

We evaluated the associations between retinal lesions and concurrent and past BP. Concurrent BP was defined as values obtained at the time of retinal photography (1997–8). Past BP was defined as the average of values obtained up to 8 years before the retinal photography (1989–97).

Definitions of vascular risk factors

Participants underwent standardised assessment of cardiovascular risk factors, including examiner administered questionnaires, electrocardiography, carotid ultrasonography, echocardiography, and blood chemistry profiles, described in detail elsewhere.13,20–23 Coronary heart disease and stroke were ascertained and classified by an adjudication process involving previous medical history, physical examination, and laboratory criteria.20 Subclinical cardiovascular disease was defined as major electrocardiogram abnormalities, echocardiogram wall motion abnormality or low ejection fraction, increased carotid or internal carotid artery wall thickness (>80th percentile) or stenosis (>25th percentile) from vascular ultrasound examination, a decreased ankle-arm systolic BP index (less than 0.9), and positive responses to the Rose Questionnaire for angina or intermittent claudication.23 Blood collection and processing for fasting glucose have been previously presented. Cigarette smoking and use of antihypertensive medication were ascertained from questionnaires.

Statistical methods

We compared characteristics between people included and excluded from this study using analysis of covariance models to adjust for age, sex, and race. Focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, and retinopathy were analysed as binary variables. The retinal arteriolar and venular diameter equivalents were initially analysed as continuous variables. The retinal arteriolar equivalent was also categorised into quintiles and generalised arteriolar narrowing was defined as the lowest quintile of the arteriolar equivalent.

We used logistic regression to determine the odds ratios for a specific retinal lesion (focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, retinopathy, and generalised arteriolar narrowing) by hypertension status and by quintiles or a 10 mm Hg increase in systolic and diastolic BP. All models were adjusted for age, sex, and race. In multivariate models, we also adjusted for presence of coronary heart disease (yes, no), stroke (yes, no), subclinical cardiovascular disease (yes, no), fasting glucose (mg/dl), cigarette smoking status (ever, never), and antihypertensive medication use (yes, no). In analyses of associations for past BP, we adjusted for concurrent BP and antihypertensive medication use (yes, no).12 We performed all analysis separately in people with and without diabetes.

To reduce the effect of magnification differences between photographs (for example, because of refractive errors), we repeated these analysis by combining the arteriolar and venular equivalents into an arteriole to venule ratio (AVR),16 with generalised arteriolar narrowing defined as the lowest quintile of the AVR. As previously reported, the AVR compensates somewhat for possible magnification differences between eyes (an AVR of 1.0 suggests that arteriolar diameters were, on average, the same as venular diameters in that eye, while smaller AVR suggests narrower arterioles).12,16

RESULTS

Among people without diabetes (n = 2056), retinal microvascular lesions were more frequent in those with hypertension, particularly those with treated but uncontrolled hypertension and those with untreated hypertension, than people without hypertension or with treated and controlled hypertension (Table 2). Compared to people without hypertension, the age, sex, and race adjusted odds ratios for treated but uncontrolled hypertension ranged from 1.2 for generalised arteriolar narrowing to 3.0 for retinopathy, while the odds ratios for untreated hypertension ranged from 1.4 for retinopathy to 4.9 for focal arteriolar narrowing. The pattern of associations was largely similar in men and women.

Table 2.

Retinal microvascular characteristics, by hypertension status, non-diabetic people

| Focal arteriolar narrowing | Arteriovenous nicking | Retinopathy | Generalised arteriolar narrowing | |||||

| No (%) | OR (95% CI) | No (%) | OR (95% CI) | No (%) | OR (95% CI) | No (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| All people* | ||||||||

| Normotensive | 785 (6.1) | 1.0 | 797 (5.9) | 1.0 | 749 (5.6) | 1.0 | 736 (17.5) | 1.0 |

| Hypertensive | ||||||||

| Controlled | 473 (5.1) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 486 (6.6) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) | 436 (6.9) | 1.1 (0.7 to 2.0) | 438 (18.9) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) |

| Uncontrolled | 338 (16.0) | 2.8 (1.8 to 4.2) | 355 (12.1) | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.2) | 344 (16.0) | 3.0 (2.0 to 4.6) | 331 (20.5) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7) |

| Untreated | 183 (24.0) | 4.9 (3.1 to 7.7) | 191 (9.4) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.9) | 178 (7.9) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.6) | 175 (28.6) | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.9) |

| Men† | ||||||||

| Normotensive | 338 (5.3) | 1.0 | 346 (5.8) | 1.0 | 319 (4.7) | 1.0 | 321 (19.0) | 1.0 |

| Hypertensive | ||||||||

| Controlled | 179 (1.7) | 0.3 (0.1 to 1.1) | 186 (5.9) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.2) | 167 (1.8) | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.3) | 166 (20.5) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) |

| Uncontrolled | 106 (11.3) | 2.3 (1.1 to 4.9) | 114 (11.4) | 2.1 (1.0 to 4.3) | 113 (14.2) | 3.2 (1.5 to 6.8) | 104 (20.2) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) |

| Untreated | 63 (15.9) | 3.6 (1.6 to 8.4) | 64 (7.8) | 1.4 (0.5 to 3.9) | 56 (10.7) | 2.5 (0.9 to 6.7) | 61 (32.8) | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.9) |

| Women† | ||||||||

| Normotensive | 447 (6.7) | 1.0 | 451 (6.0) | 1.0 | 430 (6.3) | 1.0 | 415 (16.4) | 1.0 |

| Hypertensive | ||||||||

| Controlled | 294 (7.1) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) | 300 (7.0) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) | 269 (10.0) | 1.7 (0.9 to 2.9) | 272 (18.0) | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.7) |

| Uncontrolled | 232 (18.1) | 3.1 (1.9 to 5.2) | 241 (12.4) | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.6) | 231 (16.9) | 3.0 (1.8 to 5.1) | 227 (20.7) | 1.3 (0.8 to 1.9) |

| Untreated | 120 (28.3) | 5.6 (3.3 to 9.8) | 127 (10.2) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.5) | 122 (6.6) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.4) | 114 (26.3) | 1.8 (1.1 to 3.0) |

No (%) represents the number of participants (prevalence of retinal microvascular lesion) within a specific hypertensive category. Generalised arteriolar narrowing defined as the lowest quintile of the arteriolar equivalent distribution in the population.

*Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of retinal microvascular lesion, comparing a specific hypertensive category to normotensive, adjusted for age, sex, and race.

†Odds ratio adjusted for age and race only.

All retinal microvascular lesions were monotonically associated with concurrent systolic BP. The age, sex, and race adjusted odds ratios, comparing the highest to lowest systolic BP quintiles, ranged from 1.9 for generalised arteriolar narrowing to 3.7 for focal arteriolar narrowing (Table 3). These associations were not altered in multivariate analyses adjusting for presence of cardiovascular diseases, cigarette smoking, fasting glucose, and other variables. Associations for concurrent diastolic BP were similar (data not shown).

Table 3.

Retinal microvascular characteristics, by concurrent systolic blood pressure (1997–8, at the time of retinal photography), non-diabetic people

| Focal arteriolar narrowing | Arteriovenous nicking | Retinopathy | Generalised arteriolar narrowing | |||||

| No (%) | OR (95% CI) | No (%) | OR (95% CI) | No (%) | OR (95% CI) | No (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age, sex, and race adjusted* | ||||||||

| 1st quintile | 388 (5.7) | 1.0 | 393 (4.6) | 1.0 | 357 (5.0) | 1.0 | 356 (14.0) | 1.0 |

| 2nd quintile | 372 (4.0) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.3) | 385 (4.9) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) | 353 (6.2) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.3) | 354 (18.9) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) |

| 3rd quintile | 338 (5.9) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.8) | 344 (10.5) | 2.4 (1.3 to 4.3) | 318 (5.3) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) | 315 (19.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) |

| 4th quintile | 361 (14.1) | 2.6 (1.5 to 4.3) | 375 (6.1) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.5) | 357 (10.9) | 2.2 (1.2 to 3.9) | 341 (22.6) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.6) |

| 5th quintile | 320 (19.4) | 3.7 (2.2 to 6.2) | 332 (13.3) | 3.0 (1.7 to 5.4) | 322 (14.0) | 2.8 (1.6 to 5.0) | 314 (23.6) | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.9) |

| p<0.001‡ | p<0.001‡ | p<0.001‡ | p=0.001‡ | |||||

| Multivariable adjusted† | ||||||||

| 1st quintile | 368 (6.0) | 1.0 | 374 (4.8) | 1.0 | 341 (4.7) | 1.0 | 338 (14.2) | 1.0 |

| 2nd quintile | 356 (4.2) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.3) | 368 (4.6) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.9) | 340 (6.2) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.5) | 340 (18.5) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.1) |

| 3rd quintile | 323 (6.2) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.9) | 329 (10.0) | 2.2 (1.2 to 4.0) | 305 (5.6) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.3) | 301 (20.6) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) |

| 4th quintile | 344 (14.0) | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.3) | 357 (5.9) | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.4) | 340 (11.2) | 2.3 (1.3 to 4.3) | 322 (22.7) | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.6) |

| 5th quintile | 303 (19.8) | 4.0 (2.4 to 6.9) | 314 (13.1) | 2.9 (1.6 to 5.3) | 308 (14.0) | 2.8 (1.5 to 5.2) | 296 (24.7) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.1) |

| p<0.001‡ | p<0.001‡ | p<0.001‡ | p<0.001‡ | |||||

No (%) represents number of participants (proportion with retinal lesions) by BP quintile. In multivariate models, numbers are reduced due to missing covariate data. Generalised arteriolar narrowing defined as the lowest quintile of the arteriolar equivalent distribution in the population.

*Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of retinal microvascular lesion, comparing a specific BP quintile versus the 1st, adjusted for age, sex, and race.

†Additional adjustment for presence of coronary heart disease, stroke, subclinical cardiovascular disease, fasting glucose, smoking, and antihypertensive medication use.

‡p Value represents test of increasing trend over BP quintiles.

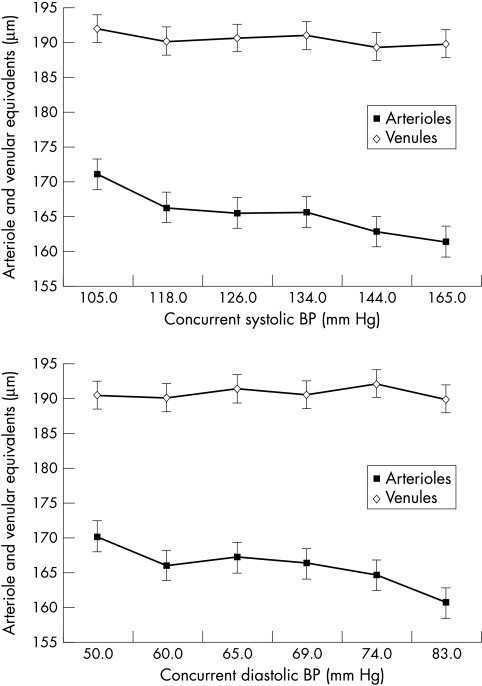

Figure 1 shows the relation between arteriolar and venular diameter equivalents and concurrent systolic and diastolic BP. Arteriolar diameter equivalents decreased with increasing concurrent systolic and diastolic BP (p<0.001 for both), suggesting that retinal arterioles were progressively narrower in those with higher BP. In contrast, venular diameter equivalent was not much changed with BP.

Figure 1.

Retinal arteriolar and venular diameters, by concurrent systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), adjusted for age, sex, and race, in non-diabetic people.

The relations between each retinal lesion and a 10 mm Hg increase in concurrent and past BP are shown in Table 4. All retinal microvascular lesions were associated with elevated concurrent BP, with adjusted odds ratio ranging from 1.11 to 1.31 and 1.17 to 1.66, for each 10 mm Hg increase in concurrent systolic and diastolic BP, respectively. Additionally, generalised arteriolar narrowing, but not other retinal lesions, was also significantly associated with past systolic (odds ratio of 1.11, p=0.008) and diastolic BP (odds ratio of 1.27, p=0.013) measured up to 8 years before retinal photography, even after adjustment for concurrent BP measurements and use of antihypertensive medication.

Table 4.

Retinal microvascular characteristics, per 10 mm Hg increase in concurrent and past systolic and diastolic blood pressure, non-diabetic people

| Focal arteriolar narrowing | Arteriovenous nicking | Retinopathy | Generalised arteriolar narrowing | |

| OR (95% CI)* | OR (95% CI)* | OR (95% CI)* | OR (95% CI)* | |

| Concurrent systolic BP, per 10 mm Hg increase | 1.31 (1.21 to 1.42) | 1.21 (1.11 to 1.32) | 1.23 (1.13 to 1.34) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18) |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.001 | |

| Past systolic BP, per 10 mm Hg increase | 1.27 (1.15 to 1.40) | 1.25 (1.12 to 1.38) | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.39) | 1.15 (1.07 to 1.24) |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | |

| Adjusted for concurrent systolic BP† | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.26) | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.32) | 1.07 (0.93 to 1.23) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.27) |

| p=0.208 | p=0.057 | p=0.382 | p=0.008 | |

| Concurrent diastolic BP, per 10 mm Hg increase | 1.66 (1.41 to 1.95) | 1.29 (1.09 to 1.52) | 1.08 (0.92 to 1.28) | 1.17 (1.04 to 1.31) |

| p<0.001 | p=0.003 | p=0.340 | p=0.010 | |

| Past diastolic BP, per 10 mm Hg increase | 1.53 (1.25 to 1.88) | 1.37 (1.11 to 1.69) | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.30) | 1.30 (1.12 to 1.50) |

| p<0.001 | p=0.004 | p=0.623 | p=0.001 | |

| Adjusted for concurrent diastolic BP† | 1.09 (0.84 to 1.42) | 1.20 (0.91 to 1.57) | 0.90 (0.69 to 1.18) | 1.27 (1.05 to 1.54) |

| p=0.522 | p=0.204 | p=0.439 | p=0.013 | |

Concurrent systolic BP represents values taken in 1997–8 (at the time of retinal photography). Past systolic BP are values averaged over 1989–97 (1–8 years before photography). Generalised arteriolar narrowing defined as the lowest quintile of the arteriolar equivalent distribution in the population.

*Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of retinal microvascular lesion, per 10 mm Hg increase in BP, adjusted for age, sex, and race.

†Additional adjustment for concurrent BP and antihypertensive medication use.

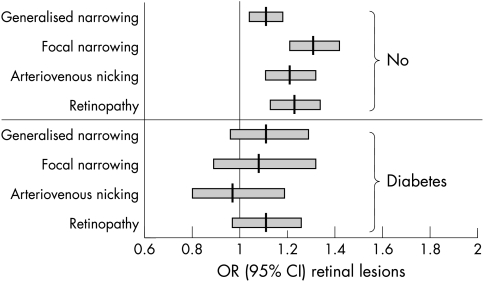

We repeated analyses in people with diabetes (n = 343). In general, although the associations were somewhat weaker in people with diabetes than in those without, the overall direction and pattern were similar (odds ratio for retinal lesions associated with a 10 mm Hg increase in concurrent systolic BP in people with and without diabetes are shown in Fig 2). Similarly, analyses stratified by age group (69–79 versus 80 and older), sex, and race did not substantially alter the results (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for retinal lesions, per 10 mm Hg increase in concurrent systolic BP, in people with and without diabetes.

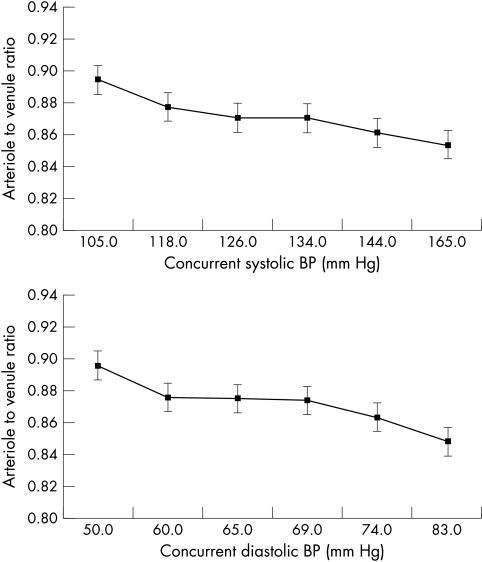

Finally, we examined the relations of the ratio of arteriolar and venular diameter equivalents (AVR) to systolic and diastolic BP (Fig 3). After adjusting for age, sex, and race, the AVR decreased with increasing concurrent systolic and diastolic BP, suggesting that retinal arterioles were progressively narrower, compared to venules, with increasing levels of BP. When we repeated all analysis with generalised arteriolar narrowing defined as the lowest quintile of the AVR, similar results as those described were found (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Retinal arteriole to venule ratio, by concurrent systolic and diastolic blood pressure, adjusted for age, sex, and race, in non-diabetic people.

DISCUSSION

Routine retinal evaluation to detect signs of retinopathy in people with hypertension is recommended for the purpose of cardiovascular risk stratification.24 However, the utility of such an evaluation is dependent on a clear understanding of the relation between hypertension status, BP, and retinal microvascular abnormalities lesions. Our current study provides important insights into these associations in a population based sample of older men and women aged 69–97 years. Firstly, we showed that people with poorly controlled or untreated hypertension were at the highest risk of having retinal microvascular abnormalities. Secondly, we found strong and graded associations between elevated BP and retinal microvascular abnormalities that were independent of the presence or absence of subclinical and clinical cardiovascular disease, cigarette smoking, fasting glucose, and use of antihypertensive medication. Finally, we demonstrated that generalised arteriolar narrowing, as ascertained from a quantitative assessment of arteriolar diameters from digitised retinal photographs, appears to be independently associated with past BP measured up to 8 years before the photography.

The association between hypertension status and retinal microvascular lesions in the CHS population is comparable with previous clinic based,2–4 and population based5–9 studies in younger people. Our study adds to these data by showing that among hypertensive people, those whose BP was uncontrolled despite treatment or who were not on treatment were more likely to have retinal microvascular lesions than those with good BP control. This pattern has also been observed in two previous population based studies that also used retinal photographic grading to define microvascular lesions. In the Beaver Dam Eye Study, non-diabetic people aged 43–84 years with untreated or uncontrolled hypertension were significantly more likely to have focal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nicking, and retinopathy than those with hypertension with adequate BP control.7 Similarly, in the Blue Mountains Eye Study, non-diabetic people aged 49 years and older with untreated or uncontrolled hypertension were more likely to have retinopathy than those with controlled hypertension.25 Since retinal microvascular lesions are correlated with end organ damage elsewhere26 and independently predict stroke,10 these data further support the importance of appropriate BP control in reducing hypertensive associated complications.

A central question has been whether some retinal characteristics, as detected clinically, reflect transient effects of elevated BP or are markers of cumulative damage from hypertension.1 To address this, we examined their associations with concurrent and with past BP. We found that generalised arteriolar narrowing was independently related to both concurrent and past BP, which is consistent with histopathological data that show retinal arteriolar narrowing results from intimal thickening and medial hyperplasia, hyalinisation, and sclerosis of arteriolar walls.11 Arteriovenous nicking was associated independently with concurrent BP and possibly past systolic BP (p=0.057). In contrast, focal arteriolar narrowing and retinopathy were related only to concurrent BP. These results are supported by data from the ARIC study that also show associations between generalised arteriolar narrowing (detected using an identical method from digitised photographs) and arteriovenous nicking with past BP measured 3–6 years before photography, despite adjustment for concurrent BP.12 Thus, both the CHS and the ARIC data support the concept that generalised arteriolar narrowing and possibly arteriovenous nicking are markers of persistent arteriolar damage from hypertension, whereas focal narrowing and retinopathy reflect more transient effects of current BP levels.

It is interesting that people with the highest quintile of blood pressure were only 1.9 times more likely to have generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing than those with the lowest quintile of blood pressure (see Table 3), suggesting that many people with higher blood pressure may not have generalised arteriolar narrowing and, conversely, many with lower blood pressure may have some degree of arteriolar narrowing. This finding is consistent with observations by Leishman3 and Scheie4 that generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing results from a combination of hypertension and arteriolosclerosis.

We found slightly weaker associations between concurrent BP and the presence of retinal microvascular abnormalities in people with diabetes (see Fig 2). This was somewhat unexpected, and appears contrary to research indicating that BP control is particularly important in reducing the risk of diabetic retinopathy.27,28 However, selective mortality may have affected these associations since it is known that among people with diabetes, those with elevated BP and retinopathy have higher mortality rates.29 Another possible explanation is that diabetes and glucose affects the physiology and anatomy of the retinal microcirculation,30,31 which may mask potential associations between BP and the presence of retinal abnormalities. In any case, differences between people with and without diabetes were modest and not statistically significant.

Of all the hypertensive retinal changes, generalised arteriolar narrowing has traditionally been the most difficult to diagnose either clinically or from standard grading of retinal photographs.1 In the CHS and the ARIC study, we developed a new approach to quantify its presence and severity by measuring diameters of retinal arterioles on digitised photographs. For analytical purposes, we defined generalised narrowing as arteriolar equivalent values falling within the lowest quintile or 20th percentile of the population distribution. An important consideration was whether potential magnification differences between photographs resulted in substantial bias in this definition (for example, vessel calibre may be artificially magnified in photographs of myopic eyes). One approach we had previously used was to combine the arteriolar and venular diameter equivalents into a ratio (the AVR), since retinas with artificially “magnified” arterioles can be expected to have “magnified” venules.16 A smaller AVR therefore indicates a narrower arterioles with respect to venules. Overall, we found no substantial difference in the association between arteriolar diameters equivalent (Fig 1) or the AVR (Fig 3) and BP. Although the AVR is understood to represent generalised arteriolar narrowing and appears to independently predict stroke,10 caution is advised regarding the use of a ratio to infer relations about its components (that is, use of the AVR to understand relations about arteriolar diameters), since spurious correlations can result.32

What are the clinical implications of the study? The strong associations between elevated blood pressure and the occurrence of retinal microvascular abnormalities in this study appear to support the current recommendations for routine retinal evaluation in people with hypertension.24 However, the retinal changes in the CHS were documented using standardised photographic and computer based grading methods. It is likely that direct ophthalmoscopy by family physicians or internists will be even more imprecise for detecting these lesions.33 Thus, it remains uncertain that a clinical retinal evaluation in people with hypertension is useful. A more immediate impact of our study findings lies in its relevance to cardiovascular research. Recent studies have suggested that an assessment of the retinal microvasculature and its changes from photographs may provide critical insights into the contribution of microvascular processes to the risk of stroke,10 coronary heart disease,34 and cognitive impairment.35

There are several limitations of this study. Firstly, selective mortality may have obscured some relevant associations and enhanced others. Retinal photography was obtained approximately 9 years after the baseline and it is possible that hypertensive participants with retinal abnormalities are more likely to die during this period, which would mask possible associations between some lesions (for example, focal arteriolar narrowing) and BP. Secondly, the CHS did not employ pharmacological pupillary dilatation before photography and used non-stereoscopic retinal photograph of only one eye to determine the presence of retinal microvascular abnormalities. As a result, there may be more variability in the grading of specific lesions, compared to grading of stereoscopic retinal photographs of two eyes taken through dilated pupils in the Beaver Dam Eye Study.6 For example, the reproducibility of the grading of focal arteriolar narrowing was only “fair to moderate” (based on the scale proposed by Landis and Koch36) and could be further improved. In fact, the imprecision may have resulted in some attenuation of the association between blood pressure and the retinal microvascular changes. Thirdly, since hypertension is strongly associated with the occurrence of retinal microvascular changes, it is possible that adjusting for concurrent BP may not be sufficient to remove its impact on the past BP associations (for example, residual confounding from concurrent BP may explain the association between past BP and generalised arteriolar narrowing). However, the consistency of the results with the ARIC study makes this less likely. Finally, these analyses were cross sectional and it is impossible to distinguish cause (for example, past BP) and effect (for example development of generalised arteriolar narrowing)

Retinal microvascular changes have recently been shown to predict stroke,10 independent of measured BP and other cardiovascular risk factors. Our data suggest that generalised arteriolar narrowing and possible arteriovenous nicking reflect persistent arteriolar damage from hypertension, which provides a possible explanation for their independent associations with stroke. These data further suggest that a quantitative assessment of retinal microvascular changes using standardised photographic techniques, including computer assisted measurements of arteriolar narrowing, may provide important information in understanding the microvascular processes associated with the development of cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Cardiovascular Health Study contract (NHLBI HC-97-06) and the American Diabetes Association (TYW).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BEK, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and their relations with hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and mortality. Surv Ophthalmol 2001;46:5980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagener HP, Clay GE, Gipner JF. Classification of retinal lesions in the presence of vascular hypertension. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1947;45:57–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leishman R. The eye in general vascular disease: hypertension and arteriosclerosis. Br J Ophthalmol 1957;41:641–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheie HG. Evaluation of ophthalmoscopic changes of hypertension and arteriolar sclerosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1953;49:117–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svardsudd K, Wedel H, Aurell E, et al. Hypertensive eye ground changes: prevalence, relation to BP and prognostic importance. Acta Med Scand 1978;204:159–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE, et al. Blood pressure, hypertension and retinopathy in a population. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1993;91:207–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE, et al. Hypertension and retinopathy, arteriolar narrowing, and arteriovenous nicking in a population. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE. The relation of systemic hypertension to changes in the retinal vasculature. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1997;95:329–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein R, Sharrett AR, Klein BEK, et al. Are retinal arteriolar abnormalities related to atherosclerosis? The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1644–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong TY, Klein R, Couper DJ, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and incident strokes. The Atherosclerosis Risk in the Communities Study. Lancet 2001;358:1134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tso MOM, Jampol LM. Pathophysiology of hypertensive retinopathy. Ophthalmology 1982;89:1132–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharrett AR, Hubbard LD, Cooper LS, et al Retinal arteriolar diameters and elevated blood pressure: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150:263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol 1991;1:263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, et al. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 1993;3:358–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association. Cclinical practice recommendations 1997. Diabetes Care 1997;20(Suppl 1):S1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hubbard LD, Brothers RJ, King WN, et al. Methods for evaluation of retinal microvascular abnormalities associated with hypertension/sclerosis in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Ophthalmology 1999;106:2269–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parr JC, Spears GFS. General caliber of the retinal arteries expressed as the equivalent width of the central retinal artery. Am J Ophthalmol 1974:472–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Parr JC, Spears GFS:Mathematic relationships between the width of a retinal artery and the widths of its branches. Am J Ophthalmol 1974:478–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Tell GS, Rutan GH, Kronmal RA, et al. Correlates of blood pressure in community-dwelling older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Hypertension 1994;23:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, et al. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, et al. Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1999;340:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbins J, Wahl P, Savage P, et al. Hematological and biochemical laboratory values in older Cardiovascular Health Study participants. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:855–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuller L, Borhani N, Furberg C, et al. Prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease and association with risk factors in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 1994;139:1164–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Sixth Report. NIH publication no 98-4080, 1997

- 25.Yu T, Mitchell P, Berry G, et al. Retinopathy in older persons without diabetes and its relationship to hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breslin DJ, Gifford RW Jr, Fairbairn JF II, et al. Prognostic importance of ophthalmoscopic findings in essential hypertension. JAMA 1966;195:335–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BE, et al. Relation of ocular and systemic factors to survival in diabetes. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:266–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tooke JE. Microvascular function in human diabetes. A physiological perspective. Diabetes 1995;44:721–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caballero AE, Arora S, Saouaf R, et al. Microvascular and macrovascular reactivity is reduced in subjects at risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 1999;48:1856–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE, et al. A cohort study of the relationship of diabetic retinopathy to blood pressure. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:601–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes:UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998;317:703–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kronmal RA. Spurious correlation and the fallacy of the ratio standard revisited. J R Stat Soc 1993;156:379–92. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimmitt SB, West JN, Eames SM, et al. Usefulness of ophthalmoscopy in mild to moderate hypertension. Lancet 1989;1:1103–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Community Study. JAMA 2002;287:1153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and cognitive impairment in middle-aged persons. The Atherosclerosis Risk in the Communities Study. Stroke 2002;33:1487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]