Extraskeletal calcification is a common complication of chronic renal failure. Numerous locations for metastatic calcification have been described. We present an unusual case of calcium deposition in the eye.

Case report

A 33 year old woman developed chronic renal failure at the age of 15 as a result of medullary cystic kidneys. She underwent a renal transplant at the age of 17, which failed 6 years later and so she was maintained on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

The patient subsequently developed refractory secondary hyperparathyroidism with ectopic calcification and reduced bone density. Her serum biochemistry between 1992 and 1997 showed a persistently high calcium phosphate product ranging between 3.6 and 8.9 mmol/l (normal range 1.6–3.4 mmol/l) with hypercalcaemia (2.36–2.71 mmol/l (normal range 2.0–2.4 mmol/l)) and hyperphosphataemia (2.36–3.42 mmol/l (normal range 0.8–1.4 mmol/l)). Systemic complications of her disease included hypertension, avascular necrosis of both hips, and reduced left ventricular function. Total parathyroidectomy was performed in 1997 with the aim of controlling her biochemical abnormalities. As a result, her calcium phosphate product had improved to 4.4–4.8 mmol/l and a year later, her bone density had returned to normal.

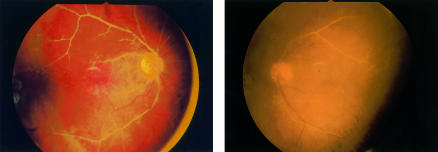

She initially presented to the eye clinic in 1994 with ocular complications of hypercalcaemia. She had recurrent episodes of conjunctivitis, band keratopathy requiring multiple excimer laser therapy, and central posterior subcapsular lens opacities. Fundus examination revealed calcified and attenuated arterioles bilaterally with ischaemic changes (Fig 1). She developed secondary neovascularisation with subsequent bilateral vitreous haemorrhages, with vision of counting fingers in the right eye and hand movements in the left eye. Pars plana vitrectomy and cataract extractions were performed in each eye, followed by a YAG capsulotomy on her left eye 4 months postoperatively. Her most recent corrected visual acuity was 6/12 in each eye.

Figure 1.

Bilateral retinal arteriolar calcification.

Comment

Metastatic calcification occurs as a result of biochemical abnormalities of calcium and phosphate. It is distinguished from dystrophic calcification, which occurs in previously damaged tissue.

Causes of metastatic calcification include abnormal dietary intake of calcium or vitamin D, extensive bone destruction as in osteomyelitis, or metastatic tumours. In patients with chronic renal failure, it is usually a consequence of secondary hyperparathyroidism. This is the physiological hypertrophy of the parathyroid glands, which occurs in response to hypocalcaemia. The resulting increase in parathyroid hormone levels causes increased bone resorption and hence a rise in serum calcium and phosphate levels.

An important factor affecting the incidence of soft tissue calcification is a high serum calcium phosphate product.1 If the concentrations of calcium and phosphorus rise beyond a critical level, their solubility product is exceeded and precipitation occurs in tissues. Visceral deposits are an amorphous or microcrystalline compound composed of calcium, phosphate, or magnesium whereas arterial deposits consist of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals.2 In arteries, calcium is principally deposited in the tunica media and internal elastic lamina.3

Common ocular sites of calcium deposition include the conjunctiva (a cause of red eyes in renal patients), and Bowman’s membrane (band keratopathy). These deposits tend to increase in extent in patients treated with regular dialysis and regress in patients receiving transplanted kidneys.4 Posterior segment calcification is less common and tends to affect the sclera and choroid. Metastatic sclerochoroidal calcifications typically occur as bilateral, multifocal, yellow fundus lesions and are usually located superotemporally.5 Massive deposition of calcium hydroxyapatite in the previtreal space in a patient with chronic renal failure has also been reported.6

The present case exhibits a unique form of metastatic calcification. In the skin, a consequence of small vessel calcification is ischaemia, which occurs as a result of endovascular fibrosis, thrombosis, or calcific obliteration.7 Theoretically, our patient’s ischaemic fundal changes may be attributed to both hypertensive retinopathy and the extensive deposition of calcium in the retinal arterioles.

This case demonstrates a dramatic and, to our knowledge, previously unreported ocular manifestation of metastatic calcification.

References

- 1.Block GA. Prevalence and clinical consequences of elevated Ca x P product in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 2000;54:318–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parfitt AM. Soft tissue calcification in uraemia. Arch Intern Med 1969;124:544–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfrey AC, Solomons CC, Ciricillo J. Extraosseous calcification-evidence for abnormal pyrophosphate metabolism in uraemia. J Clin Invest 1976;57:692–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter R, Crombie AL. Corneal and conjunctival calcification in chronic renal failure. Br J Ophthalmol 1973;57:339–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein BG, Miller J. Metastatic calcification of the choroid in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism. Retina 1982;2:76–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad R. Metastatic calcification to the peripheral fundus in chronic renal failure. Ophthalmologica 1979;179:178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer AH, Morris DJ. Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: study of three cases with literature review. Hum Pathol 1995;26:1055–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]