Birdshot retinochoroidopathy is a chronic posterior segment inflammatory disease with a characteristic clinical presentation and strong correlation with the HLA-A29 antigen.1,2 In this report, we describe the histopathological findings in the eye of a patient with this disease.

Clinical presentation

A 49 year old white man was referred to the Proctor Medical Group in 1996 for evaluation of multifocal choroiditis (MFC). This had been an incidental finding on routine examination by his primary ophthalmologist. The patient was bothered by his refractive error, but denied problems with night or colour vision, and did not notice floaters.

The patient’s past ocular history was notable for myopic correction since childhood. Radial keratotomy (RK) had been performed in both eyes in 1993, with subsequent fluctuations in his refraction. His past medical history was notable for a small cutaneous melanoma removed 5 months before presentation. He had been started on oral prednisone for his MFC before his referral to Proctor.

Best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes, and the intraocular pressures were 14 mm Hg. External examination was unremarkable, and the anterior segments showed RK scars and no inflammation. Trace vitreous cell was noted in both eyes. The optic nerve heads appeared pink and healthy, and the vasculature was unremarkable.

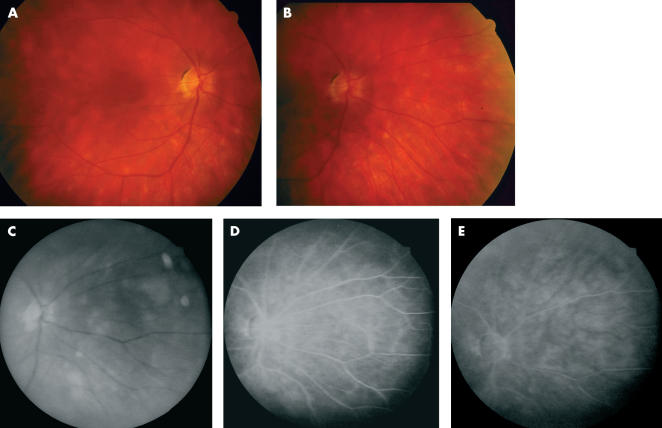

Multiple cream-coloured round and oval spots were scattered throughout the posterior poles of both eyes, more prominent nasally (Figs 1A and B). The spots averaged approximately 500 μm in diameter, and were deep to the neural retina. The macula in each eye was flat with appropriate pigmentation. The fundus had a very “blond” appearance consistent with the patient’s complexion.

Figure 1.

Clinical and fluorescein angiographic (FA) findings. (A) Right eye, posterior pole. (B) Right eye, nasal mid-periphery, showing characteristic birdshot lesions. (C) Red free photograph, right eye nasal mid-periphery. (D) FA, mid-phase, same view as (C). (E) FA, late phase, same view.

An examination for posterior uveitis included angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and lysozyme levels, a purified protein derivative (PPD) test, a chest x ray, fluorescent treponemal antibody (FTA) titres, and an HLA panel. The only remarkable finding was the presence of the HLA-A29 antigen. The characteristic fundus appearance together with the HLA-A29 antigen indicated the diagnosis of birdshot retinochoroidopathy.

The patient returned to the care of his primary ophthalmologist, and for the next 6 years perceived no changes in his visual function. Periodic fluorescein angiograms were performed during this period (Figs 1C, D, E), and on these the fundus lesions were much less evident than on clinical examination. No vasculitis, cystoid macular oedema, or optic nerve head inflammation were ever apparent.

In December, 2001, the patient sustained a myocardial infarction and died. In accordance with the patient’s wishes, the right eye was enucleated post mortem and sent to the Hogan Eye Pathology laboratory, University of California San Francisco.

Histopathological evaluation

The corneal scleral rim had been harvested (inadvertently, unaware of the history of RK) by a local eye bank. The globe was submitted in formalin and, lacking the cornea, was grossly distorted. A 4 mm segment of optic nerve was attached.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining was used to evaluate the microscopic sections.

The sclera was unremarkable. The anterior segment was markedly distorted as a result of the corneal harvesting, and it was impossible to evaluate the iris and anterior chamber angle. The lens was artefactually luxated. The ciliary body and anterior choroid appeared unremarkable.

Multiple foci of predominantly lymphocytes were located at various levels of the choroid, occasionally occupying the full choroidal thickness, and abutting the choroidal vascular channels (Figs 2A, B, C). Rare plasma cells were seen, and some foci were associated with haemorrhage. A few foci contained epithelioid cells, and there was no necrosis.

Figure 2.

Histopathological sections, haematoxylin and eosin staining. (A) Low power photomicrograph showing three foci of lymphocytic infiltrates (arrows) in the choroid (×5 magnification). (B) Higher power photomicrograph of focal lymphocytic infiltrate in the choroid. The choriocapillaris (top) is not involved (×50 magnification). (C) Choroidal lymphocytic focus abutting choroidal vessels (×50 magnification). (D) Lymphocytes surround a retinal vessel (focal retinal vasculitis) (×50 magnification). (E) Focal lymphocytic infiltrate (arrow) in prelaminar optic nerve (×25 magnification).

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) did not appear involved in the underlying choroidal process.

Additional foci of lymphocytes were found surrounding some of the retinal blood vessels (Fig 2D). The neural retina showed no cellular infiltration and appeared normal, although artefactual disorganisation of the photoreceptor outer segments made evaluation of this cell layer inconclusive.

The prelaminar optic nerve head showed an additional lymphocytic focus (Fig 2E), while the remainder of the optic nerve was unremarkable.

Conclusion

This study finds that birdshot retinochoroidopathy is characterised by lymphocytic aggregations with their foci in the deep choroid, with additional foci in the optic nerve head and along the retinal vasculature. In all likelihood, the choroidal foci correspond to the fundus spots for which this condition is well known. These histopathological findings are consistent with the angiographic observations in patients with this condition, and may explain the electroretinographic (ERG) changes seen in the advanced stages of this disease.

The characteristic fundus spots, light degree of vitreous inflammation, HLA-A29 antigen, and lack of other contributory laboratory findings strongly support the diagnosis of birdshot choroidopathy in this patient. The HLA-A29 antigen is closely associated with this condition,1,3 and this association is so well established that the diagnosis of birdshot is increasingly considered problematic without it.

The histopathological description of our patient’s eye contrasts with an earlier report describing the histopathology of a blind, phthisical eye believed to have been affected by birdshot choroidopathy.3 That eye showed diffuse granulomatous inflammation in the outer retinal layers, with less inflammation in the choroid. Important differences in clinical presentation between our patient and the patient described in that report include: (1) our patient had the HLA-A29 antigen, while the patient in that report did not; (2) our patient’s eye was neither blind nor phthisical. In light of these differences, the histopathological findings described in this report are probably more characteristic than those reported earlier for this disease.

The fundus lesions in birdshot choroidopathy did not stand out on fluorescein angiography (FA) in this patient, and lack of fluorescence is not uncommon in this condition,1 and may represent “very early” phases of the birdshot lesions.1,4 On histopathology, the neural retina, retinal pigment epithelium, and in many areas the choriocapillaris appeared unaffected by the inflammatory process, and could potentially have obscured fluorescence of the deeper structures.4 Many patients with advanced birdshot show optic nerve head inflammation and diffuse retinal vascular leakage on FA.4,5 Our patient did not have these findings, although his eye did show a small optic nerve head lymphocyte focus and limited retinal perivascular infiltration. It seems likely that these early changes would have become evident on FA eventually if they had had time to advance.

Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography reveals birdshot lesions as hypofluorescent choroidal patches which outnumber those seen clinically.6 These patches most probably correspond to the deep choroidal lymphocytic foci seen microscopically, which are hypofluorescent because they exclude the surrounding deep choroidal vasculature. Presumably, the lymphocytic foci that characterise this condition must achieve a certain diameter, density, and perhaps inward extension before being apparent clinically.

Electroretinogram (ERG) changes characteristic of this disease include a preserved a-wave, with diminished amplitude and increased latency time of the b-wave, suggesting impairment of the inner retina.7–9 Retinal vasculopathy (determined angiographically), rather than the extent of RPE/choroidal complex involvement, has also been noted to correlate with electro-oculogram (EOG) changes.7 One may speculate that the retinal perivascular lymphocytic infiltration seen in this patient progresses, in advanced stages, to inner retinal ischaemia with the observed ERG and EOG manifestations. Electroretinography was not undertaken in our patient because initially this was not essential to the diagnosis, and subsequently the patient did not follow up in our referral centre.

This report of histopathological findings in the eye of a patient with birdshot choroidopathy represents the first such description from an HLA-A29 patient. The microscopically observed changes shed light on what the fundus spots in this condition are composed of, and to some extent explain the angiographic finding in this disease.

Funding source: none

The authors have no proprietary interest in this study.

References

- 1.Gasch AT, Smith JA, Whitcup SM. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan SJ, Maumenee AE. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;89:31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nussenblatt RB, Mittal KK, Ryan S, et al. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy associated with HLA-A29 antigen and immune responsiveness to retinal S-antigen. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94:147–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeHoang P, Ryan S. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. In: Wilhelmus KR, ed. Ocular infection and immunity. St Louis: Mosby, 1996:570–8.

- 5.Soubrane G, Bokobza R, Coscas G. Late developing lesions in birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;109:204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Geronimo F, Glacet-Bernard A, Coscas G, et al. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy: measurement of the posterior fundus spots and macular edema using a retinal thickness analyzer, before and after treatment. Eur J Ophthalmol 2000;10:338–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priem HA, De Rouck A, De Laey JJ, et al. Electrophysiologic studies in birdshot chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;106:430–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirose T, Katsumi O, Pruett RC, et al. Retinal function in birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1991;69:327–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan HJ, Aaberg TM. Birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1980;90:773–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]