Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare skin neoplasm. Tang and Toker1 first described MCC in 1978 and since then 19 cases in association with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) have been reported.2–5 To the best of our knowledge, involvement of the eyelid by MCC has never been reported in the literature in association with CLL.

Case Report

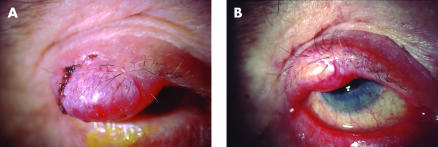

An 84 year old white man was referred with an 8 week history of a painless lump on his right upper eyelid (Fig 1A). He was complaining of visual obscuration secondary to a mechanical ptosis. Ophthalmic history was unremarkable and specifically there were no previous chalazions or trauma. On examination a firm lesion of the right eyelid measuring 2 × 1 cm with overlying telangiectatic vessels and sparing of the eyelashes was noted (Fig 1A). Further ophthalmic examination was unremarkable. General examination did not reveal any abnormalities.

Figure 1.

(A) Merkel cell tumour involving most of the upper lid causing mechanical ptosis and visual obscuration. Biopsy site is seen laterally. (B) Merkel cell tumour after treatment with radiotherapy.

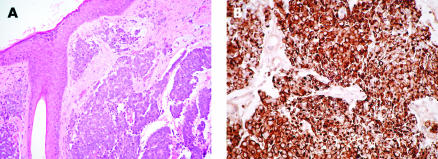

General medical history revealed that the patient had been diagnosed with CLL 11 months previously and was being treated with pulsed chlorambucil. His condition was considered to be stable by his oncologist. At the time he had a white cell count of 15.7 × 109/l. These consisted of immature lymphocytes of a B cell lineage. A full thickness incisional biopsy was performed under local anaesthesia. Histopathological examination of the biopsy sample showed an intact epidermis with the underlying dermis being infiltrated by clumps of a small cell tumour (Fig 2A). Immunostaining showed the tumour cells were negative for LCA (leucocyte common antigen), CD3 (T cell marker), CD20 (B cell marker), chromogranin, and S100 antigens. The tumour cells were positive for NSE (neuron specific enolase), EMA (epithelial membrane antigen) and CAM 5.2, which showed characteristic paranuclear accentuation (Fig 2B). Other staining techniques showed 50% of the tumour cells to be in cycle. All these features are consistent with the diagnosis of MCC.

Figure 2.

(A) Haematoxylin and eosin stain Merkel cell tumour. (B) Immunostaining with CAM5.2 showing characteristic para-nuclear accentuation.

Further investigation revealed no systemic metastasis. We opted for radiotherapy as the patient was reluctant to have surgical intervention. The patient was given a total of 40 Gy in 15 fractions. This caused the tumour to reduce in size relieving the mechanical ptosis (Fig 1B).

Comment

The recent surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) programme5 in the United States has estimated the incidence of MCC at 0.23/100 000. MCC is very rare below the age of 50 and is more common on sun exposed sites. It is an aggressive tumour with 12–45% being lymph node positive at presentation. This increases to 55–79% during the course of the disease. The 5 year survival has been reported at 30–64%.6,7 Involvement of the eyelid occurs in only 0.8% of MCC,5 and has not been reported in the literature in association with CLL.

Secondary tumours are common in B cell neoplasia with the relative risk of non-melanotic skin cancer being 4.7 in men and 2.4 in women.8 The frequency and aggressiveness of MCC and other skin neoplasms increases with immunosuppression, organ transplantation, as well as B cell neoplasia. The precise reason for such an association is not fully understood. Quaglino et al suggested that a depressed immunological system as well as exogenous oncogenic factors may, in various degrees, contribute to the development of neoplastic processes at different sites.2

The treatment is wide local excision with or without adjuvant therapy consisting of block dissection of lymph nodes or radiotherapy. Adjuvant therapy reduces local recurrence and regional failure from 39% and 46% to 26% and 22% respectively.7 Most patients die from causes directly related to the disease.7 Potentially there is an increased risk of all skin tumours including MCC in patients suffering from CLL and this diagnosis should be considered when evaluating an eyelid lesion in such patients. In a patient with reduced immunity it would be best practice to send all surgical specimens for histology even if a simple chalazion is thought to be responsible for the lid lesion.

References

- 1.Tang C, Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin: an ultrastructural study. Cancer 1978;42:2311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quaglino D, DiLeonardo G, Lallig. Association between chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and secondary tumours: unusual occurrence of a neuroendocrine (Merkell cell) carcinoma. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 1997;1:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziprin P, Smith S, Salerno G, et al. Two cases of Merkel cell tumour arising in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:525–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safadi R, Pappo O, Okon E, et al. Merkel cell tumor in a woman with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukaemia and Lymphoma 1996;20:509–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller RW, Rabkin CS. Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma: etiological similarities and differences. Cancer Epidemology, Biomarkers and Prevention 1999;8:153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw J, Rumball E. Merkel cell tumour: clinical behaviour and treatment. Br J Surg 1991;78:138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton J, Levine M, Lash R, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Surg Rev 1993;24:764–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellemgaard A, Geisler CH, Storm HH. Risk of kidney cancer and other second solid malignancies in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Eur J Haematol 1994;53:218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]