Adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium is a rare tumour. Many are diagnosed retrospectively either after excision or enucleation, as malignant melanoma is suspected.1 We report a series of four patients found to have adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium and discuss the clinical features and unusual behaviour of these neoplasms.

Case reports

We reviewed the histopathological reports in the ophthalmic pathology archive dating from 1980 to date and identified four patients who had the histopathological diagnosis of adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium. We crosschecked the details with the clinical oncology database. We reviewed their notes for features that would help us to identify this ciliary body tumour clinically. The salient features of these patients are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical details of the patients with adenoma of the pigment epithelium of ciliary body

| No | Age/sex/race | VA | Size (mm) | Clinical features | Surgery | Recurrence | Year of diagnosis | Complication |

| 1 | 40/M/W | 6/5 | 8×7×1 | Angle invasion | Local resection | No | 1992 | RD repair |

| 2 | 62/F/A | 6/6 | 5×3×1 | Angle invasion, cataract | Local resection | No | 1996 | |

| 3 | 65/F/W | 6/18 | 8×6×4 | Sentinel vessel, pigment dispersion | Local resection | No | 1998 | RD repair |

| 4 | 54/M/W | 1/60 | 5×4×4 | Secondary glaucoma, pigment dispersion | Enucleation | No | 1999 |

M = male, F = female, W = white, A = Asian, RD = retinal detachment, VA = visual acuity.

Patient 1 was reported elsewhere in 1994.2 He had a dark brown multinodular mass in the inferotemporal anterior chamber angle of the left eye. His tumour was a relatively small but invasive lesion. Patient 2 was the only non-white patient with this condition in our series. Her tumour was an incidental finding when she presented to an ophthalmologist with allergic conjunctivitis. The tumour was small and dark brown. The tumour had invaded the anterior chamber angle and the root of the iris occupying one clock hour of the angle (Fig 1A, B, and C). Adenoma of the ciliary body was suspected, as she was non-white and the degree of anterior chamber invasion appeared disproportionate to the size of the tumour.

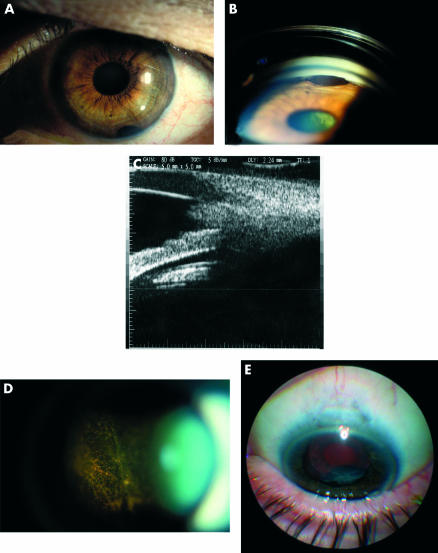

Figure 1.

(A) A small ciliary body adenoma invading the angle in patient 2. (B) Gonioscopic view of the ciliary body adenoma (A) that had invaded the angle and the root of the iris, also showing the localised cataract through the pupil. (C) Ultrasound biomicroscopy of the adenoma of ciliary body shown in (A) and (B). (D) Pigment clumps in the vitreous in patient 3. (E) Shows the adenoma of the ciliary body, the dark iris, and the trabeculectomy site in patient 4.

Floaters and blurred vision were the presenting symptoms in patient 3. The vitreous showed presence of pigment clumps and the extensive pigment dispersion made the media hazy (Fig 1D). The tumour was a solid dark brown lesion arising from the ciliary body between the 12 and 1 o'clock meridians. The clinical differential diagnosis was between malignant melanoma and adenocarcinoma of the pigment epithelium of ciliary body.

Patient 4 was initially treated for acute angle closure glaucoma in another hospital. Trabeculectomy was performed to achieve control of intraocular pressure. Postoperatively, he was found to have a lesion behind the crystalline lens. He underwent phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation to improve visualisation of the lesion. A black ciliary body mass was seen (Fig 1E). This prompted his referral to the oncology service in June 1999. Control of the intraocular pressure proved refractory even with additional medical treatment.

Pigment dispersion was seen in patients 3 and 4. This was mainly in the vitreous of patient 3 but in both the vitreous and the anterior segment of patient 4. There was heterochromia of the iris in patient 4. No angle invasion was seen in these two patients.

Other associated features were a localised cataract in patient 2, tractional retinal detachment and secondary glaucoma in patient 4. Patient 3 had an episcleral sentinel vessel over the tumour. None of these patients had any history of ocular trauma or intraocular inflammation. Ultrasound biomicroscopy (Fig 1C) helped us to evaluate these tumours in more detail.

The first three patients underwent local resection of the tumour in the form of iridocyclectomy under hypotensive anaesthesia. The last patient had enucleation as he opted to have the eye removed because of the poor visual prognosis for that eye as a result of secondary glaucoma, extensive pigment dispersion, and tractional retinal detachment.

Histopathologically, these tumours showed heavy pigmentation. Mitotic activity was absent or low. Invasion of ciliary muscle and the iris root was seen in patients 1 and 2. Patient 3 had a cystic adenoma with cells forming gland-like structures around central cysts.

Comment

Our series highlights the paradoxical behaviour of adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium. Smaller lesions invaded the angle and larger lesions caused extensive pigment dispersion although non-invasively. Angle invasion resulted in these tumours being seen and resulted in the presentation of patients 1 and 2. Blurred vision due to pigment dispersion in the vitreous resulted in the presentation of patient 3. Angle closure glaucoma and pigment dispersion were the main features of patient 4. Shields et al1 presented a series of eight patients with adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium and described their clinical features. In their series they found an association with cataract, vitreous haemorrhage, and neovascular glaucoma.

Pigment dispersion was seen in two of our patients. The presence of pigment clumps and extensive pigment dispersion in the vitreous of patient 3 (Fig 1D) is unique and has not been reported before. Chang et al3 in 1979 reported the presence of pigment in the retrolental space adjacent to the tumour in a case of adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium. Extensive pigment dispersion in vitreous had been reported in malignant melanoma of the choroid4 but to our knowledge not in adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium.

Secondary glaucoma from intraocular tumours is well known. In their survey of intraocular tumours causing secondary glaucoma Shields et al5 reported on 2704 eyes. Of the five adenomas of the ciliary body one was from ciliary pigment epithelium. None of these had secondary glaucoma. Of the ciliary body melanomas, 17% had secondary glaucoma. Angle closure was responsible for secondary glaucoma in 12% of the eyes with ciliary body melanoma. In their series in 1999 Shields et al1 had one patient who had neovascular glaucoma secondary to adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium. Patient 4 in our series presented with secondary angle closure glaucoma.

Malignant melanoma of ciliary body is known to invade the anterior chamber angle. Chang et al3 reported angle invasion in adenoma of the pigment epithelium of ciliary body. Shields et al6 reported a patient in whom invasion of the iris stroma by an adenoma of ciliary pigment epithelium was documented with progressive growth. They initially suspected this to be a tumour of the iris but on later evaluation showed the origin from the ciliary body. The presenting feature in patients 1 and 2 in our series was similar, although the ciliary body origin was recognised initially. In patient 2 the diagnosis of adenoma of ciliary body was strongly suspected preoperatively, as the tumour that had invaded the angle was very small. Invasion of the angle by ciliary body melanomas usually does not occur until they have attained a larger size. Invasion of the angle has also been described in melanocytoma of the ciliary body.7 They too tend to be relatively larger when they invade the angle, unlike the adenomas that we described. Iris melanocytomas undergo central necrosis and cause pigment dispersion and glaucoma.8 However the necrotic centre is absent in adenomas.

One of our patients (patient 1) had a sentinel vessel. Sentinel vessels are typically thought to be associated with malignancy. However, this is not always the case. Presence of a sentinel vessel indicates ciliary body involvement. Fine needle aspiration biopsy may be considered for aiding diagnosis of malignancy. However, its role in the diagnosis of these lesions may be limited. Absence of malignant cells does not always rule out the presence of malignancy.

Our study highlights the paradoxical behaviour of adenoma of the pigment epithelium of ciliary body that has not been emphasised before. Adenoma of the pigment epithelium of the ciliary body should be kept in mind if there is extensive pigment dispersion by larger tumours and invasion of the anterior chamber angle by relatively small tumours.

References

- 1.Shields JA, Shields CL, Gunduz K, et al. Adenoma of the ciliary body pigment epithelium: the 1998 Albert Ruedemann, Sr, memorial lecture, part 1. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:592–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rennie IG, Faulkner MK, Parsons MA. Adenoma of the pigmented ciliary epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:484–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang M, Shields JA, Wachtel DL. Adenoma of the pigment epithelium of the ciliary body simulating a malignant melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1979;88:40–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Baba F, Hagler WS, De la Cruz A, et al. Choroidal melanoma with pigment dispersion in vitreous and melanomalytic glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1988;95:370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields CL, Shields JA, Shields MB, et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of secondary intraocular pressure elevation in eyes with intraocular tumours. Ophthalmology 1987;94:839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shields JA, Eagle RC, Shields CL, et al. Progressive growth of benign adenoma of the pigment epithelium of the ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1859–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LoRusso FJ, Boniuk M, Font RL. Melanocytoma (magnocelluler nevus) of the ciliary body: Report of 10 cases and review of literature. Ophthalmology 2000;107:795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fineman MS, Eagle RC, Shields JA, et al. Melanocytomalytic glaucoma in eyes with necrotic iris melanocytoma. Ophthalmology 1998;105:492–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]