Abstract

Aims: To investigate whether cryopreserved donor cornea could be used for therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) to eradicate the infection, obviate complications, and preserve anatomical integrity in severe fungal keratitis.

Methods: In this retrospective, consecutive case series, 45 eyes of 45 patients with severe fungal keratitis, which exhibited anterior chamber collapse, corneal perforation, and/or large suppurative corneal infiltrate, received therapeutic PKP after removal of the infected corneal tissue, irrigation of the anterior chamber by 0.2% fluconazole solution, iris dissection of fibrinoid membrane, and iridectomy and therapeutic PKP using corneas cryopreserved at −20°C.

Results: Among 45 eyes, 39 eyes (86.7%) were successfully eradicated the fungal infection without recurrence and maintained their anatomical integrity without any complication. Four of 45 eyes (8.9%) showed postoperative rise of intraocular pressure, of which three were controlled with subsequent antiglaucoma surgeries, whereas one eye needed additional antiglaucoma medications. Two of 45 eyes (4.4%) were enucleated because of uncontrollable fungal infection and secondary retinal detachment, respectively. 23 eyes received subsequent optical PKP and, among them, 21 maintained clear corneal grafts and two suffered from graft failure due to allograft rejections.

Conclusion: Cryopreserved donor corneas are effective substitutes in therapeutic PKP to control severe fungal corneal infection and preserve the global integrity, and may offer additional advantages over conventional PKP in reducing allograft rejection, eradicating fungal infection during the postoperative period, and improving the success of optical PKP for visual rehabilitation.

Keywords: fungal keratitis, penetrating keratoplasty, corneal tissue, itraconazole, fluconazole

Because of the recent development of more potent but less toxic antifungal agents, major advances have been made in the treatment of local and systemic fungal infections, especially if definite diagnosis and proper management are made at an early stage.1–11 Nevertheless, refractory fungal keratitis still possesses a therapeutic challenge as it may progress to corneal perforation and fungal endophthalmitis.12–17 Without prompt and effective management, accompanied inflammation may also result in extensive anterior or posterior iris synechia, secondary intractable glaucoma, and even extrusion of intraocular contents.12–17 To arrest infectious progress, avoid disastrous complications, and preserve the globe integrity, therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) has been advocated for severe fungal keratitis.18–27

We report here that donor cornea preserved at −20°C may be an alternative tissue for therapeutic PKP in severe fungal keratitis. We also discuss how cryopreserved corneas might have theoretical advantages over the conventional corneas for therapeutic PKP in such a clinical setting. Furthermore, the timing and surgical technique of this procedure and selection of antifungal agents are also discussed based on our experiences gained in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study of consecutive case series, approved by the institutional ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from each patient who participated in this study.

Patients

From May 1995 to May 2001, there were 45 eyes of 45 patients that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were those patients who had severe fungal keratitis and received therapeutic PKP using cryopreserved donor cornea. Furthermore, corneal scraping for microbial cultures was made before surgery and definite fungal pathogens were identified in all patients. The exclusion criterion was that postoperative follow up should be at least 6 months. There were 31 males and 14 females, with a mean age of 40.1 (SD 11.2) years (range 23–67 years). Before surgery, these patients demonstrated one of the following signs of the corneal fungal infection and the surgery was considered inevitable. Twenty nine eyes showed collapse of the anterior chamber by fibrinoid membrane formation following hypopyon absorption when the fungal infection had been controlled by antifungal medications (Fig 1A). Fourteen eyes showed a small corneal perforation despite the fungal infection had partially been controlled by antifungal agents as judged by clinical results showing clearing of infiltrate margins, drying of ulcer bases, lessening of hypopyon, and regression of conjunctival hyperaemia (Fig 2A). One eye showed a large corneal perforation concomitant with extensive suppurative necrosis (Fig 3A). Three eyes showed an infiltrate larger than 8 mm in diameter and corneal ulceration with retrocorneal plaque or anterior chamber inflammatory mass. The fungal hyphae penetrating through the Descemet’s membrane and spreading into the anterior chamber were suspected in this situation.

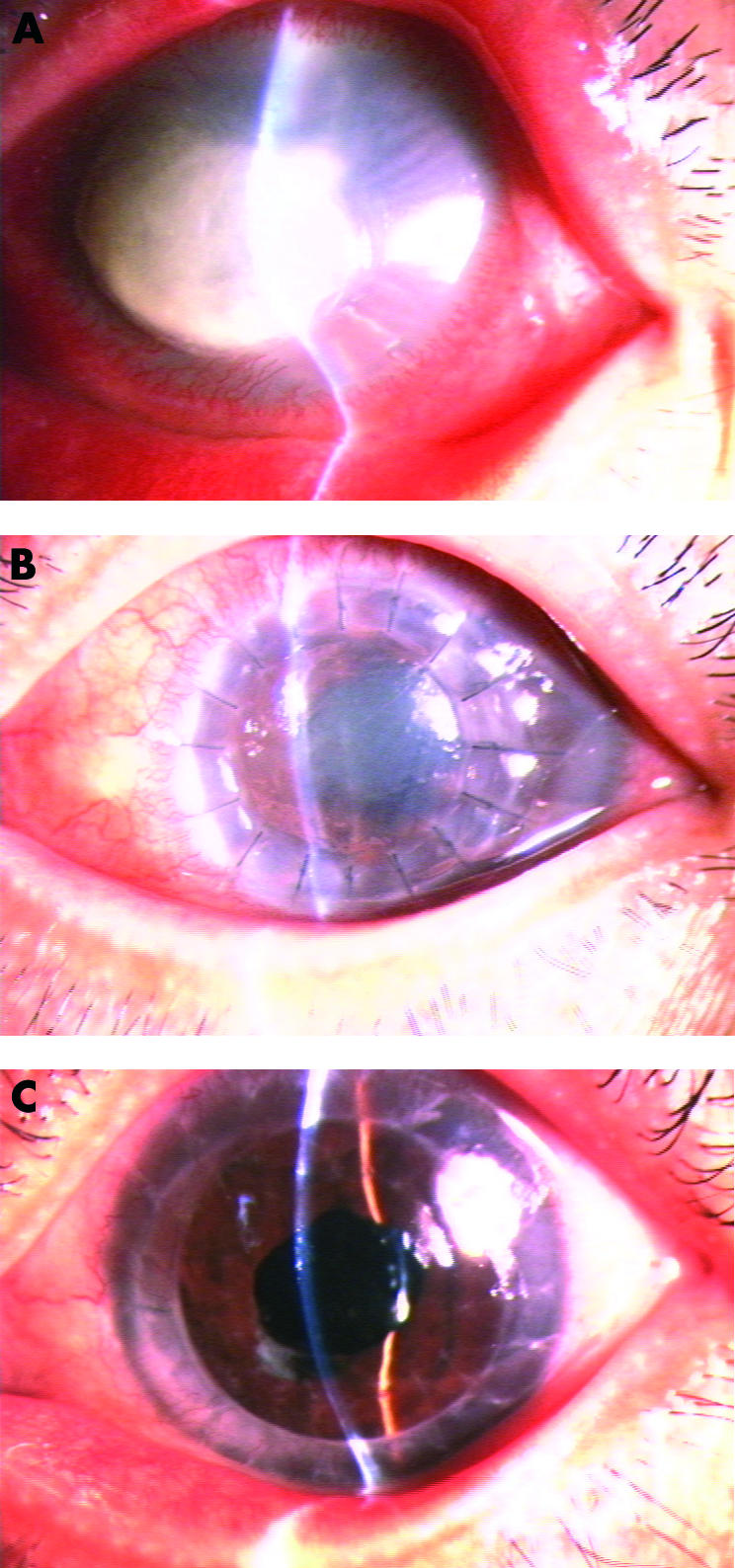

Figure 1.

(A) Case No 1 was a 56 year old female with Aspergillus corneal infection in her left eye for 37 days. The whole anterior chamber collapsed due to extensive fibrinoid membrane formation following absorption of severe hypopyon. (B) Thirty four days after therapeutic PKP using a cryopreserved donor cornea. An eccentric corneal graft which was mildly cloudy was noted concomitantly with mild conjunctival hyperaemia. A deep anterior chamber, posterior synechia of the iris, and cataract were observable through the mildly oedematous corneal graft. (C) Nine months after therapeutic PKP, the patient received a centric optical PKP and ECCE with IOL implantation. The second corneal graft had been clear for 28 months and the final visual acuity was 20/32.

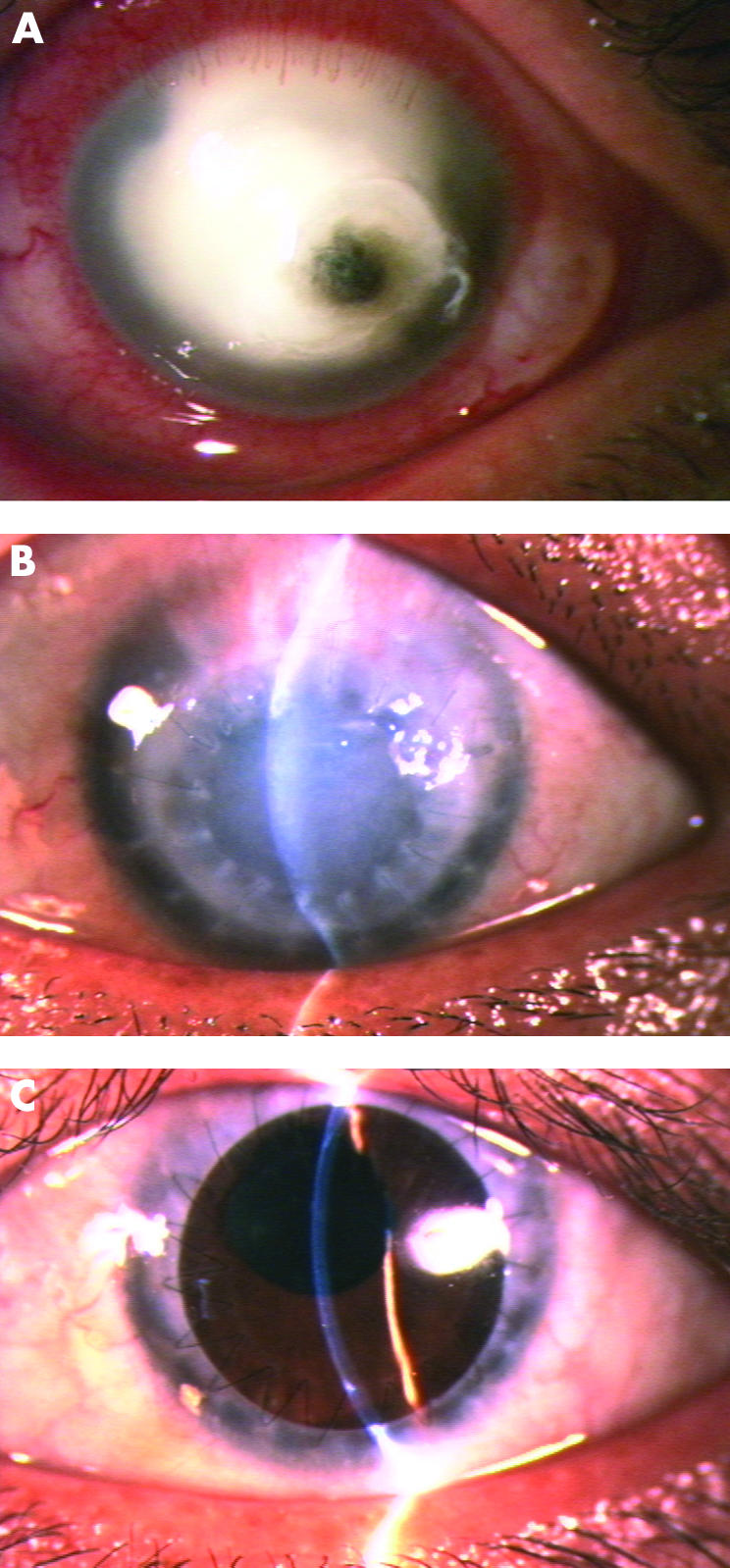

Figure 2.

(A) Case No 2 was a 34 year old female with Fusarium corneal infection in her left eye for 29 days. A large corneal infiltrate with a small perforation and a flat anterior chamber were observed. (B) Seven months after therapeutic PKP using a cryopreserved donor cornea. An eccentric corneal graft with significant stromal oedema and a reconstructed anterior chamber, and non-conjunctival inflammatory reaction were noted. The peripheral recipient corneal margin had become scarred. (C) The patient received an optical PKP 7 months after therapeutic PKP, resulting in a clear and centric corneal graft for 8 months, with a partial anterior synechia and a mildly irregular pupil. The final visual acuity was 20/20.

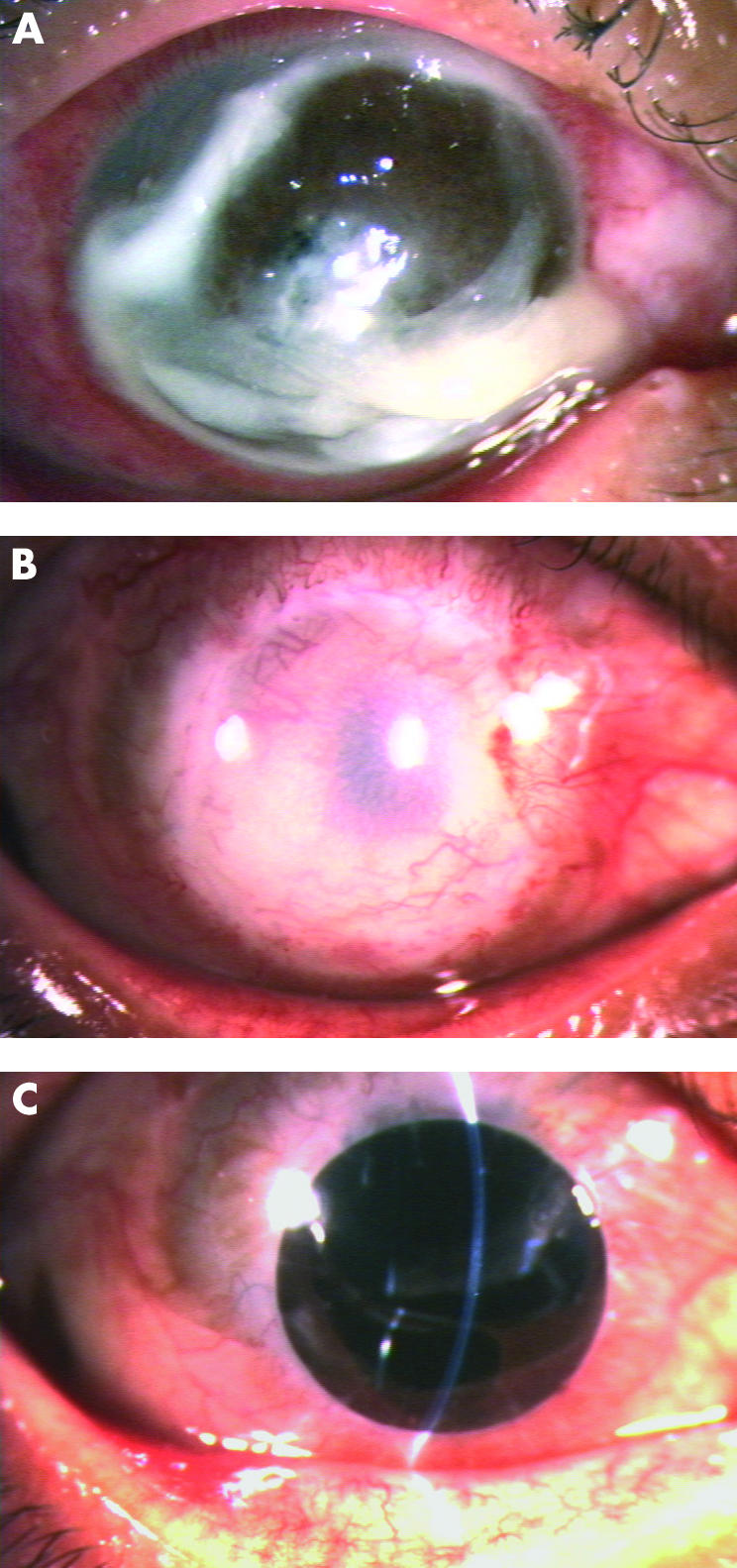

Figure 3.

(A) Case No 3 was a 38 year old male with Verticillium corneal infection in his right eye for 21 days. An extremely large corneal perforation concomitant with extensive suppurative tissue necrosis was noted. (B) A large cryopreserved corneal button involving the whole perforation and infiltrate area was transplanted at 6 months after therapeutic PKP. There was corneal scarring with moderate neovascularisation. The patient exhibited elevated intraocular pressure, which was controlled by a subsequent trabeculectomy combined with intraoperative 0.02% mitomycin C for 5 minutes. (C) The patient received a centric optical PKP and ECCE with IOL 6 months after therapeutic PKP resulting in a clear corneal graft for 5 months with a dilated pupil, and the IOL was mildly dislocated upward. The final visual acuity was 20/125.

Donor corneal preparation

All donor corneas were evaluated and preserved at Zhejiang University Eye Bank, had primary corneal endothelial deficiency or cell loss, and were pronounced unsuitable for optical PKP. They were then preserved at −20°C in a balanced salt solution (Alcon Lab, Inc, TX, USA) containing 50 μg/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 μg/ml neomycin, and 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B. The average duration of cryopreservation before surgical use was 9.5 (SD 8.3) months.

Surgical techniques

All therapeutic PKPs were performed by the same surgeon (YYF). If the corneal infection was associated with pre-Descemet’s ulcer or small perforation, corneal trephination was performed with caution and a diamond knife was used to enter the anterior chamber followed by injection of a viscoelastic material to deepen the peripheral anterior chamber and release anterior synechia. Corneal scissors were used to complete the trephination. If corneal perforation was large and concomitant with severe suppurative necrosis, and trephination was thought to be impossible, the suppurative tissue was removed by forceps and scissors, and the irregular margin of recipient bed was trimmed by scissors. In non-perforated corneas either with invisible anterior chamber or with severe hypopyon, trephination was performed to involve the entire infiltrate in the same manner as conventional PKP. After the infected corneal tissue was removed and the recipient bed was prepared, the anterior chamber was washed with 50 ml fluconazole solution (2 mg/ml) through a blunt 27 gauge needle to clean the fibrinoid purulence. The fibrinoid membrane on the iris surface and/or on the pupil area was carefully peeled off by forceps. If the recipient bed was round, a donor corneal button with 0.5 mm oversize was chosen, whereas if the recipient bed was irregular, the donor cornea was trimmed to fit the bed. The donor-recipient junction was sewn by 10-0 Nylon interrupted sutures. An iridectomy was performed through a limbal paracentesis or through the donor-recipient junction. At the end of the surgery, the anterior chamber was deepened by BSS (Alcon Lab, Inc, TX, USA). The crystalline lens was inadvertently removed in one eye during the removal of fibrinoid membrane; all others were left untouched even though some opacity was noted during therapeutic PKP.

Medications and follow up

Based on the clinical impression of fungal keratitis after scraping, oral itraconazole 300 mg daily was immediately initiated for all 45 patients at the time of their referral. In 14 patients, a combination of oral itraconazole 300 mg daily and intravenous fluconazole 200 mg twice daily was added 5–7 days after oral itraconazole treatment because no significant improvement was observed. In addition, subconjunctival injections of 0.2% fluconazole (1 ml) twice daily were added in seven of these 14 patients. Additionally, all patients received 3% ofloxacin eye drops (Santen Pharmaceutical Co, Osaka, Japan) four times daily to prevent bacterial infection. The same regimen that demonstrated its efficacy preoperatively was continued postoperatively. During systemic administration of antifungal agents, the levels of hepatic enzymes were monitored every 2 weeks. If there was a rise of hepatic enzymes, the systemic drugs were tapered or withdrawn. Otherwise, these drugs were tapered according to the regression of conjunctival hyperaemia, corneal infiltration and inflammatory reaction in the anterior chamber. After complete resolution of inflammatory reaction, oral itraconazole 100 mg daily was still continued for one more month.

All patients were hospitalised for the first 7–10 days after operation, and were followed up weekly for the first month, every 2 weeks for 2 months, monthly for a minimum of 6 months, and at different intervals thereafter.

RESULTS

Microbial pathogens isolated from these 45 eyes included Fusarium (14), Aspergillus (12), Verticillium (7), Microsporum (5), Streptomyces (3), Nocardia (1), Mucor (1), Epidermophyton (1), and Aureobasidium (1).

After therapeutic PKP, all 45 patients were followed up for a mean of 13.9 (SD 6.8, range 7–37) months. Thirty nine of 45 eyes (86.7%) showed successful eradication of corneal fungal infections without recurrence, and their globe integrity was preserved without intractable complications after surgery. Four of 45 eyes (8.9%) developed elevated intraocular pressure after surgery even though corneal fungal infection was eradicated. Three of these four eyes with secondary glaucoma were successfully treated with a trabeculectomy combined with intraoperative application of 0.02% mitomycin C for 5 minutes; the remaining one required additional antiglaucoma medications. One of 45 eyes (2.2%) was enucleated as the fungal infiltration spread into the graft and the sclera shortly after surgery, and resulted in extensive corneoscleral melt. One of 45 eyes (2.2%), in which the crystalline lens was simultaneously removed during therapeutic PKP, lost its light perception 2 months after surgery because of retinal detachment, and was eventually enucleated as a result of phthisis.

One day after surgery fibrinoid exudate in the anterior chamber was remarkably visible in 31 of 45 eyes, but regressed thereafter, and the anterior chamber was cleared in 7 days after surgery. Seven of 45 eyes were left with a retrocorneal membrane. Complete corneal epithelialisation was observed in 5 days following therapeutic PKP in 44 of 45 eyes. Within 1 month after surgery, the corneal graft had mild oedema but was sufficiently clear enough to observe the anterior chamber. From then on, increasing stromal oedema and opacity in the graft was observed, but the anterior chamber was still visible. Corneal scarring of the graft and of the recipient peripheral cornea gradually occurred but neovascularisation was usually mild to moderate (Fig 1B, 2B, 3B).

With respect to antifungal medications, 31 patients received only oral itraconazole either preoperatively or postoperatively. Fourteen patients received a combination of oral itraconazole and intravenous injections of fluconazole, of whom seven received additional subconjunctival injections of 2 mg/ml fluconazole twice daily for 7–10 days. Although intravenous and subconjunctival injections of fluconazole were withdrawn in 2 weeks in these 14 patients, oral itraconazole was continued in 43 patients for a period of 2.3–3.9 months (mean 3.06 (0.56) months). Eight patients demonstrated temporary elevation of hepatic enzymes during systemic antifungal administration, but returned to a normal level after withdrawal of intravenous fluconazole and/or tapering of the oral itraconazole dosage.

Twenty three of 45 eyes (51.1%) were subsequently regrafted by optical PKP using donor corneas with a healthy endothelium at least 6 months following therapeutic PKP. The optical PKP was performed in all these eyes with a smaller recipient bed size (ranged from 7.25 to 7.50 mm in diameter) than the original therapeutic PKP. Eleven eyes received simultaneous extracapsular cataract extraction and posterior chamber IOL implantation during the optical PKP. During the extracapsular cataract extraction, a fixed pupil with posterior synechia was observed in five eyes, which required sphintectomies to enlarge the pupil, and suturing at the conclusion. During the follow up period of 5–31 months (mean 12.4 (8.1) months) after optical PKP, two of 23 eyes (8.7%) experienced a graft failure as a result of immunological rejection and 21 of 23 eyes (91.3%) retained a clear graft (Fig 1C, 2C, 3C). Postoperatively, the final visual acuity was 20/50 or better in 17 (73.9%) eyes, and 20/200 or better in 20 (86.9%) eyes, and less than 20/200 in three (13.0%) eyes of these 23 eyes.

DISCUSSION

It was apparent that fungal keratitis in these 45 eyes had developed into a very serious condition. This was attributed partly to the fact that most patients lived in remote rural areas and were inaccessible to modern medical facilities. Therefore, on patient referral, diagnosis and proper management for the fungal keratitis had been delayed. Owing to the severity of fungal keratitis, we performed therapeutic PKP using cryopreserved donor corneas. Thirty nine of 45 eyes (86.7%) showed successful eradication of fungal infections and preservation of globe integrity following this type of therapeutic PKP in conjunction with systemic and/or subconjunctival triazole antifungal agents. Four of 45 eyes (8.9%) were complicated by secondary glaucoma, and two of 45 eyes (4.4 %) were enucleated because of uncontrollable fungal infection and retinal detachment, respectively.

Several surgical interventions have been proposed for treating fungal keratitis, including simple debridement, excisional keratectomy, cover of conjunctival flap and therapeutic PKP.15,16,19,23,25 Our results support the notion that therapeutic PKP is an effective means of eradicating the infection and preserving the globe integrity,18–27 and in many circumstances is inevitable. Previously, healthy donor corneas have been used for therapeutic PKP in severe fungal keratitis.18–27 An obvious disadvantage is the fact that immunological graft rejection occurs more often in these eyes with active inflammation. Killingsworth et al23 believed that the main purposes of therapeutic PKP are to control refractory corneal infection and to tectonically re-establish the structural integrity of the eye globe. Therefore, it makes no difference if a donor cornea button is obtained with or without a healthy endothelium. The use of cryopreserved corneas without a healthy endothelium also solves the problem of donor shortage in China. The present study demonstrated that cryopreserved donor corneas could still be used effectively for therapeutic PKP in treating severe fungal keratitis even in such a case with an extremely large perforation (Fig 3A and B). Cryopreserved corneas at −20°C can be stored for a long time, and satisfy the emergency need of therapeutic PKP. Because the cryopreserved donor cornea is devoid of live cells, there is no need to use postoperative corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents to prevent or suppress allograft rejection, obviating reactivation of fungal infection. After the global integrity has been preserved and ocular inflammation has subsided for a while, a smaller optical PKP can be performed electively for visual rehabilitation. This may increase the likelihood of success of optical PKP.

Several points of surgical techniques are worth mentioning. The first is that the timing of surgical intervention should balance the need to minimise the risk of spreading fungal pathogens to a deeper tissue by surgery if the infection is not controlled and the need to restore globe integrity to minimise the risk of secondary glaucoma. Thus, we advise that the therapeutic PKP be performed after initiation of antifungal drugs for 7–10 days when the cornea is not perforated or has only a small perforation. This was based on our observation that oral itraconazole alone or combined with systemic and subconjunctival fluconazole for 3–7 days had a significant effect in controlling corneal fungal infection judged by the clearing of the infiltrate margin, drying of the ulcer base, lessening of hypopyon, and regression of conjunctival hyperaemia. However, if the cornea has a large perforation, therapeutic PKP should be performed sooner if not immediately. The second important point is to wash the anterior chamber with 0.2% fluconazole, carefully remove fibrinoid membrane extending onto the iris/lens surface, and lyse the anterior synechia as thoroughly as possible. The third point is to perform an iridectomy at the end of the surgery to prevent secondary glaucoma especially as we noted that there was invariably postoperative fibrin exudation. The fourth point is to avoid removing the crystalline lens even if it appears opaque during therapeutic PKP to preserve the iris-lens diaphragm so that the spread of fungal pathogens into the vitreous cavity can be prevented. The cataract surgery can be easily and safely performed during secondary optical PKP.

There is no doubt that selection of antifungal agents is critical for treating severe fungal keratitis. Triazoles are newly developed antifungal agents with broad spectrum antifungal action, and have been used widely in treating systemic fungal infections and in ophthalmic mycoses such as keratomycoses and fungal endophthalmitis.1–11 We thus chose itraconazole, in some cases combined with fluconazole, in this study. Itraconazole, one of the triazoles, is a broad spectrum, orally active, triazole, has favourable pharmacokinetics, and is effective against many mycopathogens with low toxicity.1–3 Although itraconazole and fluconazole are triazoles, itraconazole can only be used orally, and fluconazole can be used orally and also intravenously and subconjunctivally. Previous studies have demonstrated that there is a difference in the antifungal spectrum between itraconazole and fluconazole.1–3 Multiple routes of administration have been suggested for fluconazole in treating keratomycosis.15 Our data demonstrated that simultaneous multiple routes and a combined use of itraconazole and fluconazole could control the fungal keratitis in 14 cases, which initially showed a delayed response to itraconazole. Further controlled clinical studies are needed to substantiate the necessity of simultaneous multiple routes of itraconazole and fluconazole administration in corneal fungal infections.

In the treatment of keratomycosis, another problem is to prevent its recurrence. Previous studies have shown that recurrences occur upon withdrawal of antifungal agents,15 presumably due to incomplete extermination of the fungal pathogen in the tissue. To guard against the recurrence, criteria to guide the drug tapering and withdrawal are important. In this study we relied on clinical judgments, such as complete resolution of conjunctival hyperaemia, no infiltration except oedema in the corneal graft, and no cells in the anterior chamber. With all of these criteria met, oral itraconazole 100 mg daily is continued for one more month. This guideline led us to a clinical cure without recurrence in all 43 cases of keratomycosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sheehan DJ, Hitchcock CA, Sibley CM. Current and emerging azole antifungal agents. Clin Microbio Rev 1999;12:40–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Rosso JQ, Gupta AK. Oral itraconazole therapy for superficial, subcutaneous, and systemic infection. A panoramic view. Postgrad Med 1999;Spec No:46–52. [PubMed]

- 3.Guzek JP, Roosenberg JM, Gano DL, et al. The effect of vehicle on corneal penetration of triturated ketoconazole and itraconazole. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1998;29:926–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarro J, Akiti T, Almada-Horta R, et al. Mycotic keratitis due to curvularia senegalensis and in vitro antifungal susceptibilities of curvularia spp. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:4170–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton K, Miller D, Pflugfelder SC. Corneal chromoblastomycosis. Cornea 1997;16:235–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thakar M. Oral fluconazole therapy for keratomycosis. Acta Ophthalmol 1994;72:765–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Day DM. Orally administered antifungal therapy for experimental keratomycosis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1990;88:685–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan M, Panda A, Gupta SK. Management of human keratomycosis with miconazole. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1989;17:295–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Khan R, Sharma S, et al. Clinical and experimental mycotic corneal ulcer caused by Aspergillus fumitatus and the effect of oral ketoconazole in the treatment. Mycopathologia 1989;106:133–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt C, Perel Y, Harousseau JL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of itraconazole oral solution in neutropenic children during long-term prophylaxis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001;45:1561–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luttrull J, Wan WL, Kubak BM, et al. Treatment of ocular fungal infections with oral fluconazole. Am J Ophthalmol 1995;119:477–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah CV, Jones DB, Holz ER. Microsphaeropsis olivacea keratitis and consecutive endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:142–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang MX, Shen DJ, Liu JC, et al. Recurrent fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis. Cornea 2000;19:558–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Feuer W, et al. Endophthalmitis associated with microbial keratitis. Ophthalmology 1996;103:1864–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liesegang TJ. Fungal keratitis. In: Kaufman HE, Barron BA, Mcdonald MB, eds. The cornea. 2nd ed. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998:219–45.

- 16.Arffa RC. Grayson’s diseases of the cornea. 3rd ed. Chap 10. St Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1991:199–223.

- 17.Mizunoya S, Watanabe Y. Paecilomyces keratitis with corneal perforation salvaged by a conjunctival flap and delayed keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 1994;78:157–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh G, Malik SR. Therapeutic keratoplasty in fungal corneal ulcers. Br J Ophthalmol 1972;56:41–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forster RK, Rebell G. Therapeutic surgery in failures of medical treatment for fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1975;59:366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanitato JJ, Kelley CG, Kaufman HE. Surgical management of peripheral fungal keratitis (keratomycosis). Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:1506–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fong LP, Ormerod LD, Kenyon KR, et al. Microbial keratitis complicating penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology 1988;95:1269–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nobe JR, Moura BT, Robin JB, et al. Results of penetrating keratoplasty for the treatment of corneal perforations. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:939–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Killingsworth DW, Stern GA, Driebe WT, et al. Results of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology 1993;100:534–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panda A, Khokhar S, Rao V, et al. Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in nonhealing corneal ulcer. Ophthalmic Surg 1995;26:325–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cristol SM, Alfonso EC, Guildford JH, et al. Results of large penetrating keratoplasty in microbial keratitis. Cornea 1996;15:571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg P, Gopinathan U, Choudhary K, et al. Keratomycosis: clinical and microbiologic experience with dematiaceous fungi. Ophthalmology 2000;107:574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonas JB, Rank RM, Budde WM. Tectonic sclerokeratoplasty and tectonic penetrating keratoplasty as treatment for perforated or predescemetal corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]