Ocular toxoplasmosis may be remarkably atypical in situations of evident immunosuppression such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, malignancy, and use of chronic immunosuppressive drug therapy.1 Aggressive forms in immunocompetent hosts are very rare.2,3 We present a case of severe, bilateral necrotising retinitis by Toxoplasma gondii initially misdiagnosed as an acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome, in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diabetes mellitus type 2, who was taking medium dose prednisone.

Case report

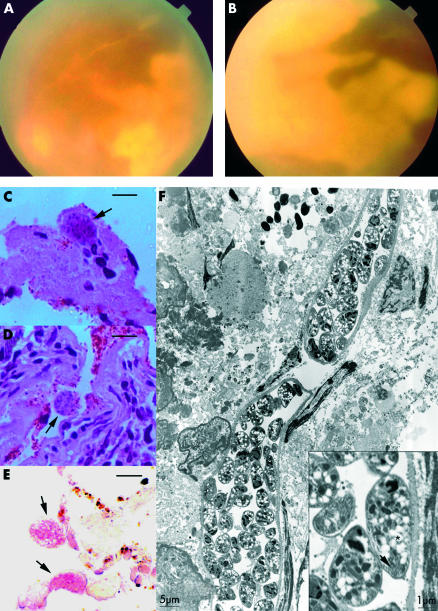

A 47 year old woman reported a 3 month history of rapid visual loss in the right eye followed by a decrease in her left eye vision 2 months later. Twenty days before the onset of ocular symptoms the patient had a seizure. Her medical history showed a SLE,4 with an active lupus central nervous system disease controlled with prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/day), and type 2 diabetes mellitus. At her first visit to our service, visual acuity was hand movements in both eyes. Slit lamp examination showed 3+ aqueous cells and flare, and 2+ anterior vitreous cells in both eyes. The fundus showed a 2+ vitreous haze and almost 360° creamy white necrotising retinitis extending from the ora serrata to the posterior pole, including the macula in both eyes (Fig 1A and B). Thumbprint patches at the border between necrotic and scanty normal retina could be observed, and also diffuse vascular attenuation.

Figure 1.

(A) Fundus appearance of the left eye. (B) Fundus appearance of the right eye. (C) Light micrograph shows necrotic retina with occasional inflammatory cells and Toxoplasma cyst (arrow). (D) Light micrograph shows the necrotic retinal pigment epithelium with Toxoplasma cysts (arrow) and the choroid with a dense infiltrate of lymphocyte and plasma cells (haematoxylin and eosin, bar = 10 μm). (E) Immunohistochemistry with alkaline phosphatase. Two Toxoplasma cysts (arrows) positively dyed pink (bar = 10 μm). (F) Electron micrograph of a paraffin embedded tissue post processed for electron microscopy of the chorioretinal biopsy shows two Toxoplasma cysts with micronemes (inset, arrow) and white spherules with hazy borders amylopectin granules (inset, asterisk). The inset shows higher magnification of a bradizoite, showing typical apical structures. Magnification is represented in standard bars.

Cerebral spinal fluid analysis showed pleocytosis, hypergammaglobulinaemia, and negative serology, including VDRL. Complement level was normal, anti-double stranded DNA and anti-cardiolipin (ACL) antibodies were negative, and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was normal, not fulfilling the international consensus criteria to antiphospholipid syndrome.5 Serum anti-Toxoplasma and anti-herpes virus IgG were positive by enzyme immunoassays, while anti-HIV-1 and HIV-2 was negative. Tests for specific IgM were all negative; serum FTA-Abs was positive; VDRL was negative. Complete blood count and platelets were normal. Chest x ray was also normal.

A presumptive diagnosis of ARN was made in a patient with active systemic lupus disease. Intravenous aciclovir was introduced and prednisone therapy was maintained.

Owing to failure of the antiviral treatment and ocular disease progression, the patient underwent a chorioretinal biopsy of the right eye for a definite diagnosis, mainly to discharge a tumoral retinochoroidal infiltration. Two blocks of choroid and retina, and also a vitreous sample, were obtained. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was unexpectedly positive for T gondii and negative for the herpesvirus family (CMV, HSV-1 and HIV-2, VZV), Treponema pallidum, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The biopsy showed a necrotic retina, with few remaining retinal cells. Within the necrotic retina there were occasional lymphocytes and a number of T gondii cysts (Fig 1C). The choroid was densely infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig 1D). T gondii in the necrotic retina was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Fig 1E). Inside intact cyst walls, viable Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites bearing micronemes, polysaccharide granules, and apical complex were observed at electron microscopy (Fig 1F). Desmont’s coefficient was negative (anti-T gondii vitreous titre = 2256; anti-T gondii serous titre = 2736; total vitreous IgG = 678 mg/dl; total serous IgG = 1314 mg/dl).

Based on these results, aciclovir was discontinued and oral anti-Toxoplasma treatment was initiated with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid supplementation. After a 1 month treatment retinal lesions started to heal, yet no improvement of visual acuity was observed.

Comment

The present case was atypical because of an extensive bilateral necrotising retinitis and obliterative vasculitis, with no pre-existing chorioretinal scars. Three factors could have conferred a mild degree of immunosuppression to this patient: SLE, diabetes mellitus,6,7 and prednisone at medium dose.8 It is recognised that retinal vasculitis and immunosuppression increase the risk of a herpetic9 and, to a lesser extent, a toxoplasmic, infection. Ocular toxoplasmosis associated with collagen vascular disorders is a rare event10 and has been described after aggressive immunosuppressive therapy. On the other hand, retinal vasculitis occurs in less than 10% of SLE patients, particularly in those presenting with antiphospholipid syndrome, which makes them susceptible to retinal infection.11 In the present case, laboratory findings consistent with antiphospholipid syndrome were absent. The pre-existence of widespread SLE retinal vasculopathy could be inferred by the active lupus central nervous system disease.12 Therefore we speculate that the active SLE associated with diabetes mellitus and the use of corticosteroid increased the patient’s susceptibility to infection leading to this atypically severe ocular toxoplasmosis.

The causative agent was initially diagnosed as T gondii based on PCR analysis of a vitreous sample and confirmed by histopathological findings of the chorioretinal biopsy. In the present case, the biopsy was also useful to discharge any tumoral infiltration.13 Although the local production of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies is also considered a useful parameter, the high intraocular total IgG titre found in this case, probably caused by a breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier, was responsible for the false negative Desmont’s coefficient. The simple observation of Toxoplasma cysts is not indicative of active infection. However, the presence of multiple cysts, aside from a positive immunohistochemistry test in a symptomatic patient, allowed an accurate diagnosis.

Taking into account that the fundus characteristics strongly suggested a herpetic acute retinal necrosis, one could interpret the PCR as being a false negative result because of both, either a previous aciclovir treatment14 or a lack of sensitivity. Nevertheless, the disease progression despite antiviral therapy, the absence of any viral particles on electron microscopy, in conjunction with all the evidence pointing to a toxoplasmic retinitis, makes the possibility of a combined infection still possible, but remote.

Based on the present case that showed an atypically severe form of ocular toxoplasmosis in a patient with a vasculopathy because of collagen and metabolic vascular disorders, we suggest that cases of severe necrotising retinitis be evaluated expeditiously to exclude conditions that mimic ARN. A less invasive vitreal PCR and, when indicated, an early retinochoroidal biopsy may yield a definite diagnosis avoiding any delay in introducing effective treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by FAPESP no 98/00256-3. Dr Heitor Franco de Andrade Junior of the Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, University of São Paulo School of Medicine, provided helpful suggestions for revision of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis in the immunocompromised host. Int Ophthalmol 1989;13:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabates R, Pruett RC, Brochkurst RJ. Fulminant ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1981;92:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girard P, Kohen D, Chevalier C, et al. Necrose retinienne aigue et toxoplasmose oculaire. Bull Soc Ophtalmol 1984;84:751–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries AS, et al. The 1982 classification criteria of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson WA, Gharavi AE, Koike T, et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report on an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1309–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moutschen MP, Scheen AJ, Lefebvre PJ. Impaired immune responses in diabetes mellitus: analysis of the factors and mechanisms involved. Relevance to the increased susceptibility of diabetic patients to specific infections. Diabete Metab 1992;18:187–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson, MW, Greven, CM, Jaffe, GJ, et al. Atypical, severe toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis in elderly patients. Ophthalmology 1997;104:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson D, Wolchok E. Ocular toxoplasmosis in an adult receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 1976;94:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rappaport KD, Tang WM. Herpes simplex virus type 2 acute retinal necrosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Retina 2000;20:545–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Held R, Eckardt C. Bilateral traction detachment in necrotizing retinitis as a sequela of toxoplasmosis. Fortschr Ophthalmol 1990;87:206–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinkhoff AV, Beattie CW, Chalmers A. Retinopathy in systemic lupus erithematosus: relationship to disease activity. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1152–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafford-Brady FJ, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, et al. Lupus retinopathy. Patterns, association and prognosis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:1105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Topilow HW, Ackerman Al, Friedman A . Progressive outer retinal necrosis (letter). Ophthalmology 1995;102:1737–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toyoda M, Carlos JB, Galera OA, et al. Correlation of cytomegalovirus DNA levels with response to antiviral therapy in cardiac and renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 1997;63:957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]