A lthough the treatment of microbial keratitis has changed with the introduction of new antimicrobials, the management principles still remain the same. In general, suspected microbial keratitis is treated with empirical therapy of intensive topical broad spectrum antimicrobials. This is because delaying treatment until the diagnosis is confirmed may worsen the visual outcome and allow further complications. Whether there is a need for microbiological investigation for all patients is contentious, as is empirical primary treatment with fluoroquinolone monotherapy.

WHAT CAUSES MICROBIAL KERATITIS?

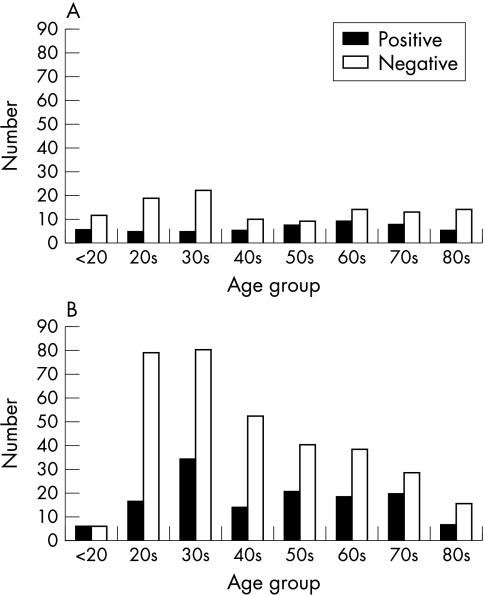

Microbial keratitis is rare in the absence of predisposing risk factors. In the past trauma and ocular surface compromise (for example, bullous keratopathy, exposure, etc) were the major risks. However, with the introduction of soft contact lenses and their widespread use since the 1980s, the demographic profile of those presenting with suspected microbial keratitis has changed. Figure 1 shows the demographic change in the age groups of those presenting with suspected microbial keratitis from 1985 to 1995 at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, United Kingdom.

Figure 1.

(A) Corneal scrape results by age group, Moorfields Eye Hospital, 1985. (B) Corneal scrape results by age group, Moorfields Eye Hospital, 1995.

The change in the presentation of suspected microbial keratitis over time was also reflected in the types of micro-organisms cultured as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variation in the organisms cultured from corneal scrapes at Moorfields Eye Hospital from 1985 to 1995

| Staphylococcus sp | Streptococcus sp | Pseudomonas | Gram negatives | Acanthomoeba | Fungi | |

| 1985 | 29% | 22% | 19% | 25% | 0% | 13% |

| 1995 | 34% | 13% | 21% | 12% | 13% | 6% |

Not only are there temporal changes in the pattern of presentation of microbial keratitis, there are also geographic differences in the pattern of presentation. Table 2 shows the different patterns of infection from reports of keratitis from various locations around the world.

Table 2.

Regional variation in the organisms cultured from corneal scrapes

| Staphylococcus | Streptococcus | Pseudomonas | Gram negatives | Fungi | |

| New York, USA | 49% | 9% | 8% | 22% | 3% |

| Florida, USA | 16% | 8% | 19% | 9% | 35% |

| South Africa | 45% | 29% | 4% | 14% | 3% |

| Nepal | 23% | 37% | 11% | 14% | 17% |

| Bangladesh | 2% | 24% | 22% | 5% | 45% |

| Melbourne, Australia | 48% | 13% | 7% | 14% |

So it is evident that the empirical choice of antibiotics in the primary treatment of suspected microbial keratitis requires local contemporaneous data regarding the spectrum of disease. For such data to be collected it is necessary for patients to have a microbiological investigation, which not only provides information on the pattern of presentation, but may also provide important information regarding the change in antibiotic sensitivities with time.

DOES THIS MEAN THAT EVERY PATIENT SHOULD BE SCRAPED FOR MICROBIOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION?

Certainly there is evidence that this not the norm among general ophthalmologists in the United States. A survey by McDonnell in 1992 found that only 14 (23%) of 64 randomly selected general ophthalmologists considered a scrape necessary all the time.1 Perhaps the change in presentation of suspected microbial keratitis at Moorfields provides part of the explanation; there are more young patients, probably contact lens wearers, often with a negative corneal scrape culture. The availability of potent monotherapy “off the shelf” has also allowed general ophthalmologists to treat suspected microbial keratitis successfully without the need to refer patients to corneal specialists who would be more likely to use microbiological investigation and extemporaneous fortified topical antibiotic preparations.

The yield from microbiological investigation may be low, despite the direct inoculation of the sample onto culture media at the time of the scrape. Reviewing the results from 18 published studies (3836 patients), a positive culture averaged 51% (95% confidence interval 34–67), and a positive Gram stain averaged 67% (95% CI 60 to 75). There are probably a number of reasons for the low yield, such as the variability in the diagnosis, operator skill producing a variable quality sample, and techniques of culture, to name but a few. However, the ulcer size definitely has an effect on the culture yield. In the UK Ofloxacin Study2 ulcer size was a significant influencing factor for the 49 of 118 (42%) patients that were culture positive (Table 3), suggesting that the microbiological investigation of corneal ulcers less than 2.0 mm2 in size is probably not worthwhile.

Table 3.

Distribution of ulcer sizes and their culture results from the UK Ofloxacin Study2

| 25th quartile | Median | 75th quartile | |

| Positive culture | 2.00 mm2 | 6.0 mm2 | 12.00 mm2 |

| Negative culture | 0.25 mm2 | 1.0 mm2 | 2.25 mm2 |

p<0.0001 Kruskal-Wallis H.

The risk of primary treatment failure varied in previous reports from 4% to 28%, the UK Ofloxacin Study found that 12% (14 of 118) failed primary treatment, and 10 of the 14 required some form of surgical intervention. Those with persistent or indolent ulceration (15 of 188, 13%) were found to have previous ocular surface disease (relative risk 12.65, 95% CI 1.72 to 93.1), or previous topical steroid use (RR 4.61, 95% CI 1.88 to 11.08). Slowly healing ulcers (17 patients, 14%) were also related to ocular surface disease (RR 14.5, 95% CI 1.98 to 105.48) but also a positive culture (RR 4.58, 95% CI 1.59 to 13.2).2

Thus, the results from the UK Ofloxacin Study suggest that young patients with small ulcers do well and are unlikely to be culture positive. However, large (>5 mm2) culture positive ulcers in elderly patients (>60 years old) had 5.5 times the risk of primary treatment failure than others. Culture positive ulcers were also more likely to take longer to heal.2

For the individual patient, a positive culture result from microbiological investigation is more often useful as a prognostic indicator than having diagnostic significance, given that 80%+ will be treated satisfactorily with empirical broad spectrum antibiotics. However, as already stated, the combined local results from microbiological investigation will guide the ophthalmologist’s choice of empirical therapy in the first place. When an individual fails primary treatment, an initial positive culture result will guide the choice of secondary therapy, perhaps reducing further delay in resolution of the infection.

SHOULD PRIMARY TREATMENT OF SUSPECTED MICROBIAL KERATITIS RELY ON FLUOROQUINOLONE MONOTHERAPY?

Obviously the local demographic and the clinical presentation must influence the choice of therapy. In urban societies, for those unlikely to fail primary treatment (that is, young patients with a small ulcer), monotherapy with an “off the shelf” preparation is a convenient low risk option. This would seem to be common practice as the McDonnell survey suggested.1

For the “at-risk” population, the elderly with large ulcers and previous ocular surface disease, ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin monotherapy were as effective as the previous convention (fortified gentamicin combined with a fortified cephalosporin) in a number of randomised controlled trials.3–5 However, if there are concerns about the possibility of a pneumococcal infection or there are resistant Gram positive organisms within the local demographic, a combination of the fluoroquinolone and a fortified cephalosporin would be a better alternative to fortified gentamicin. Although efficacious, fortified aminoglycosides are considerably more toxic to the ocular surface than fluoroquinolones, and may result in delayed healing, and other problems. Cephazolin 5% would be a good choice—add 2.5 ml to 1000 mg cephazolin powder then add to 17 ml Liquifilm Tears; this will be stable for 28 days if refrigerated.

In the UK Ofloxacin Study resistant organisms were found in both treatment arms of the trial, and primary treatment failure occurred equally as often for the conventional therapy (fortified cefuroxime and gentamicin) as it did for ofloxacin monotherapy.2 So it is important to be able to recognise those patients at risk of primary treatment failure (for example, the elderly with large ulcers), and have a management algorithm that identifies and manages those treatment failures early, regardless of the initial treatment instituted.

OTHER MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Often it is much easier to start than to stop the treatment. The signs of resolution are subtle; however, the symptoms are often a good early guide. Toxicity from the treatment may obscure signs of resolution, particularly if the initial intensive treatment is overly prolonged and utilises toxic antibiotics such as the aminoglycosides. So treatment should be considered as two phases—the initial intensive treatment to sterilise the cornea, followed by the healing phase, with prophylactic doses of antimicrobials to prevent further infection.

Initial treatment should be intensive with hourly application of antibiotic to “marinade” the eye so that the corneal tissue is rapidly saturated with a high antibiotic concentration. A high concentration (usually exceeding the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) by a number of log units) can be achieved within a few hours, so that 48 hours of sustained high concentrations is usually enough to eliminate most bacterial infections, sometimes even those organisms only partly sensitive to the antibiotic. Sustained intensive treatment day and night for the first 48 hours, then hourly by day for the next 2–3 days, would allow for more than an adequate chance of sterilising the corneal ulcer. Admission to hospital to ensure compliance and observe the clinical response is frequently required for the elderly with large ulcers, particularly if there is corneal thinning. For smaller shallow ulcers a shorter intensive period may be adequate, and these may be managed on an outpatient basis. The results from any corneal scrape, with sensitivities, may be used to rationalise or modify treatment at 48 hours. It is worthwhile adding oral doxycycline to the therapy if the ulcer is large and there is corneal thinning. At a dose of 100 mg twice a day, doxycycline is a metalloproteinase inhibitor and may help prevent corneal perforation.6

Lack of clinical response requires secondary management which is best undertaken by corneal specialists, especially if an exotic organism is involved or if corneal perforation is impending.

Following the initial treatment phase the antibiotic application is reduced to four times a day to allow for healing of the epithelial defect. Tapering the initial therapy offers no clinical advantage and is only likely to increase the likelihood of toxicity. The healing phase may be prolonged for large culture positive ulcers, especially in the elderly who may also have ocular surface disease. It is important to optimise the ocular surface environment, correcting any factors such as aqueous tear deficiency, Meibomian gland disease, exposure, etc. Topical steroids are often required to settle the resultant inflammation from the keratitis and may ultimately be necessary to promote healing of the epithelial defect.7,8 These are used with caution in those patients who had fungal keratitis; however, a pronounced inflammatory response from a fungal infection may be difficult resolve otherwise. Poor healing ulcers may require management by a corneal specialist.

CONCLUSIONS

The initial management of suspected microbial keratitis with intensive empirical antimicrobials is largely successful with whatever primary management regime used. However, the unique combination of pathogen and host response may result in an adverse outcome despite optimal management.9 Vigilance and a secondary management algorithm for such cases is required. It is the early identification of those at risk, and those that are failing the initial management, that will prevent loss of the eye and ultimately improve the chance of an acceptable visual outcome for the patient.

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonnell PJ, Nobe J, Gauderman WJ, et al. Community care of corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;114:531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morlet N, Minassian D, Butcher J. Risk factors for treatment outcome of suspected microbial keratitis. Ofloxacin Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:1027–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks DJ Abrams DA, Sarfarazi FA, et al. Comparison of ciprofloxacin to conventional antibiotic therapy in the treatment of ulcerative keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1993;115:471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien TP, Maguire MG, Fink NE, et al and the Bacterial Keratitis Study Research Group. Efficacy of ofloxacin vs cefazolin and tobramycin in the therapy for bacterial keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:1257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ofloxacin Study Group. Ofloxacin monotherapy for the primary treatment of suspected microbial keratitis. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1902–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralph RA. Tetracyclines and the treatment of corneal stromal ulceration. Cornea 2000;19:274–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leibowitz Hm, Kupferman A. Topically administered corticosteroids. Effect on antibiotic-treated bacterial keratitis. Ophthalmology 1980;98:1287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern GA, Buttross M. Use of corticosteroids in combination with antimicrobial drugs in the treatment of infectious corneal disease. Ophthalmology 1991;98:847–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coster DJ, Badenoch PR. Host, microbial and pharmacological factors affecting the outcome of suppurative keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1987;71:96–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FURTHER READING

- The American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred practice pattern bacterial keratitis. San Francisco: AAO.

- Allen BDS, Dart JKG. Strategies for the management of microbial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1995;79:777–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu HC. Microbiological aspects of fluoroquinalones. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;112:15S–24S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TTL, Sethi C, Daniels JT, et al. Mattrix metalloprotienases in disease and repair processes in the anterior segment. Surv Ophthalmol 2002;47:239–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]