Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is the most common ocular adnexal lymphoid proliferation. These neoplastic lesions have a more indolent course than non-MALT lymphomas, are usually found in the older age groups (50–70 years), are usually limited to localised (stage I) disease at presentation, and radiotherapy and chemotherapy have been the mainstay of treatment.1

Case report

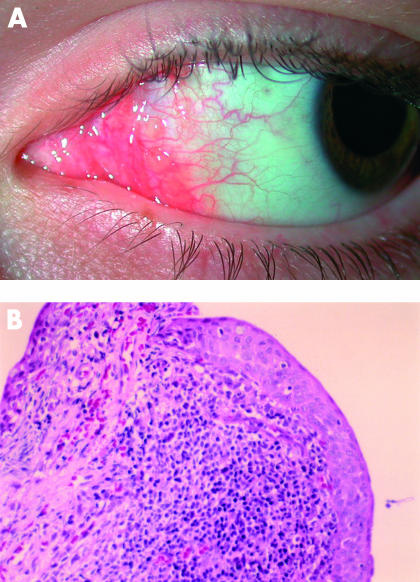

A 15 year old male was referred by an ophthalmologist after an 8 month history of unusual painless follicles at both nasal fornices (Fig 1A). There were no visual symptoms and, based on a working diagnosis of an atypical vernal reaction, topical steroid treatment had resulted in mild size reduction of the lesions. Incisional biopsy was performed after the lesions remained static for 3–4 months.

Figure 1.

(A) Conjunctival MALT lymphoma, nasal fornix of left eye. (B) Histological section of conjunctival mucosa demonstrating dense lymphoid infiltrate (haematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×200).

The patient’s visual acuity was 6/4 in both eyes and intraocular pressures measured 15 mm Hg in each eye. Slit lamp examination demonstrated small follicular deposits in both nasal fornices and nasal palpebral conjunctiva. The rest of the ocular examination was unremarkable. Review of systems was negative and the patient’s past medical history and family medical history did not reveal the presence of lymphoproliferative or autoimmune diseases. There were no findings suggestive of Sjögren’s syndrome and physical examination was normal.

The limited amount of biopsy tissue was divided for routine processing and flow cytometry; frozen tissue was therefore unavailable. Histologically a dense lymphoid infiltrate including benign appearing lymphoid follicles was identified (Fig 1B). Lymphoid follicles were surrounded by centrocytic-like cells and small lymphocytes, some of which infiltrated the conjunctival epithelium. Flow cytometry identified a monoclonal B cell population with a CD5−, CD20+, CD10 equivocal phenotype. The histopathological findings in isolation may have represented either an early marginal zone lymphoma or a benign B cell follicular hyperplasia. Absolute distinction on the small amount of tissue was not possible. However, in conjunction with the flow cytometric finding of a monoclonal B cell population, a diagnosis of low grade B cell lymphoma (probably of MALT type) could be made.

Systemic disease was excluded after the following investigations: lumbar puncture; bone marrow aspirate and trephine; CT chest, abdomen, pelvis and sinuses; gallium scan. The patient was subsequently treated with 10 intralesional injections of 10 × 106 IU of interferon alfa (IFN-α) over a 4 week period; no side effects were noted during this time. Complete resolution was achieved at 2 months, with no sign of recurrence after 18 months’ follow up.

Comment

Conjunctival lymphoma is mostly a disease of the elderly, with Shields et al reporting a mean age of diagnosis of 61 years.2 While not a common disease, Akpek et al suggest that its prevalence is higher than previously recognised, and that vigilance is required in patients with chronic ocular irritation and conjunctivitis who do not respond to conventional therapy.3 This is the youngest case of conjunctival lymphoma that we know of in the literature; hence conjunctival lymphoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of atypical conjunctival lesions in younger patients.

Treatments outlined by Shields et al included radiotherapy (44%), complete excisional biopsy (36%), observation (9%), chemotherapy (6%), and cryotherapy (4%).2

Radiotherapy has been widely used with successful results3–6 but ocular morbidity in the form of corneal ulcer, radiation induced cataract and ocular lubrication disorders have been reported.4,7 Intralesional IFN-α is a relatively new therapy which has been shown to be both effective and safe in a small number of cases.1,5,8,9 Non-sight threatening ocular complications such as subconjunctival haemorrhage and local chemosis have been reported, as well as minor transient systemic effects including headaches, nausea, fevers, chills, and myalgia.5 Administration of intralesional IFN-α is also a relatively simple and quick procedure. It shows great promise as a first line agent to treat conjunctival lymphoma, but long term follow up is needed.

References

- 1.Blasi MA, Gherlinzoni F, Calvisi G, et al. Local chemotherapy with interferon-α for conjunctival mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Ophthalmology 2001;108:559–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields CL, Shields JA, Carvalho C, et al. Conjunctival lymphoid tumours. Clinical analysis of 117 cases and relationship to systemic lymphoma. Ophthalmology 2001;108:979–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akpek EK, Polcharoen W, Ferry JA, et al. Conjunctival lymphoma masquerading as chronic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 1999;106:757–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heuring AH, Franke FE, Hütz WW. Conjunctival CD5+ MALT lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:498–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahill MT, Moriarty PA, Kennedy SM. Conjunctival “MALToma” with systemic recurrence. Arch Ophthalmol 1998; 116:97–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scullica L, Manganelli C, Turco S, et al. Bilateral non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the conjunctiva. Eye 1999; 13:379–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessel EM, Henk JM, Whitelocke JF, et al. Ocular morbidity after radiotherapy of orbital and conjunctival lymphoma. Eye 1987;1:90–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lachapelle KR, Rathee R, Kratky V, et al. Treatment of conjunctival mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with intralesional injection of interferon alfa-2b. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:284–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cellini M, Possati GL, Puddu P, et al. Interferon alpha in the therapy of conjunctival lymphoma in an HIV+ patient. Eur J Ophthalmol 1996;6:475–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]