Abstract

Background: 214 orthoptists’ infants have been followed for up to 15 years, relating neonatal misalignment (NMs) behaviour to onset of convergence and 20 Δ base out prism response, and also to later childhood ocular abnormalities.

Methods: In a prospective postal survey, orthoptist mothers observed their own infants during the first months of life and regularly reported ocular behaviour and alignment, visual development, and any subsequent ocular abnormalities.

Results: Results confirm previously reported characteristics of NMs. Infants who were misaligned more frequently were misaligned for longer periods (p <0.01) and were later to achieve constant alignment (p <0.001) but were earlier to attempt first convergence (p = 0.03). Maximum NM frequency was usually found at or before the onset of first convergence (p = 0.0002).

Conclusions: NMs occur in the first 2 months of life and usually reflect a normally developing vergence system. They appear to represent early attempts at convergence to near targets. Emerging infantile esotropia is indistinguishable from frequent NMs before 2 months.

Keywords: convergence, development, esotropia, infants, refractive error

Ocular behaviour in early infancy is immature. Acuity and contrast sensitivity are low (for reviews see Atkinson1 and Held2) and refractive error common until later childhood.3–7 There is a consensus that binocular vision, in terms of the ability to resolve random dot stereograms, does not develop until 12–16 weeks of life.8–12 Vergences and accommodation are immature and largely unresponsive to varying target demand.13–15 There is no clear evidence that any reliable accommodation/convergence linkages are present at this time,14,15 and if present, convergence accommodation may be just as, or more, influential than accommodative convergence.13,15 Nevertheless, when active convergence is not required, most infants’ eyes appear broadly aligned (once corrections for the large angle lambda* of infancy have been made)16–18 and studies suggest that a primitive vergence system may exist before 12 weeks that is not dependent on cortical binocularity.12,16,19

Parents of visually normal children often comment that their eyes had been “all over the place” in their first weeks. In a booklet issued to all new parents in the United Kingdom, the advice is given “at birth a baby’s eyes may roll away from each other occasionally”.20 General practitioners and health visitors only refer intermittent squinting if it persists after about 3 months of age. However, if the intermittent “strabismus” reaches an ophthalmologist before the infant is 4 months of age, these misalignments may be considered pathological. Two recent papers suggest that early intermittent esotropia resolves in 27% of referred cases,21,22 especially if they present under 12 weeks of age. The relatively small numbers reported (175 subjects provided by 137 investigators at 104 clinical paediatric ophthalmology sites) suggest that these early deviations form a very small part of the clinical ophthalmology caseload. But perhaps, instead of being rare, early squinting is so common and normal that it rarely reaches eye professionals.

A longitudinal study by the author of a group of 75 normal infants of orthoptists18 found that most neonates’ eyes were broadly aligned for most of the day, but the majority (88%) of infants showed brief periods of intermittent squinting†. The deviations were overwhelmingly short lived, convergent, large angle, unilateral, and alternating. I term these “neonatal misalignments” (NMs) because “esotropia” implies an abnormality that may not be present. Although the time scale sometimes falls outside the 1 month limit of “neonatal,” the majority of NMs do occur within the first month and are generally reducing by 2 months of age.

In later infancy, intermittent strabismus is always pathological, but the 1993 data, along with anecdotal reports, suggested that NMs are of little significance. It is possible that instead of being part of a pathological spectrum of esotropia, intermittent misalignment is normal behaviour that may “tip over” into, or overlap with, pathology, especially if excessive in early infancy, or abnormally persistent.

A second, longitudinal cohort study of 1150 children23 showed that there were subtle consequences of NMs. There was a small but significant association of frequent NMs in the first 8 weeks with later hyperopia and myopia, as well as with clinically significant esotropia or esophoria at 4 years of age, while never showing NM was significantly associated with later astigmatism.

This paper reports the orthoptists’ infants study in more detail, including additional data on the nature and frequency of NMs in an extended group that was not analysed in the original publication. The original group18 now also includes a number of infants who developed pathological strabismus and refractive error, who were excluded from the 1993 report. Unreported data on the development of convergence in relation to NMs and later refractive error are also presented. A companion paper reports in more detail the NM behaviour of those children who went on to develop referable abnormalities in later childhood. NMs will be shown to be a common occurrence of early infancy with important relevance to the development of vergence eye movements and later abnormalities.

METHODS AND SUBJECTS

Recruitment has already been described in detail.18,24 Orthoptist mothers were recruited while pregnant and reported their infant’s ocular behaviour on postal questionnaires at the end of the first and second weeks of life, monthly up to 6 months and then at 1.0, 3.5 and 5.0 years. Numbers are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Numbers followed at each age group

| Age | No |

| Up to 3 months | 215 |

| Up to 6 months | 188 |

| up to 1 year | 159 |

| Up to 3.5 years | 98 |

| Up to 5 years | 66 |

| >6 years | 55 |

Observations of the frequency, characteristics, and stimuli to misalignment were made (specifically not using corneal reflection position because the large angle lambda of infancy can be misleading17,25–28). Basic orthoptic tests were also carried out by the mothers, looking at quality of fixation, gross pursuit movements, convergence to near point from birth, and 20Δ base out prism response from 3 months. Refractive, visual, or motility defects were reported at diagnosis. All neonatal observations were made before any subsequent ocular abnormalities were detected.

Analysis was carried out using SPSS software. t Tests, ANOVA, and Tukey’s post hoc tests were used for parametric data and χ2 tests for non-parametric data.

RESULTS

Characteristics of neonatal misalignments

The additional dataset collected since 1993 showed no systematic difference from the original study results.24 The data have been pooled to provide greater power to the analysis. These extended results will be described briefly.

Transient esodeviations are common in months 1–4. In month 1, 73.2% were misaligned at some time (21.6% less than once a day, 15% once a day, 23.2% up to 10% of the time, 7.8% for 11–30% of the time, and 4.7% for more than this). They were reducing by 2 months (when only 49% of subsequently normal infants showed any deviation at all) and, in the visually normal infants, gone by 4 months.

The only infants (n=2) still misaligned at 4 months were in the process of developing true infantile esotropia, confirming the findings of The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group.21,22 All other infants were constantly aligned at 4 months. Those destined to develop subsequent manifest deviations of later onset were all aligned, with normal binocular and acuity responses, until at least 2 years of age.

The two infants destined to be infantile esotropes were indistinguishable from the subsequently normal children in the first 2 months with frequent, but not constant, esodeviation. However, when the “normals” started to show fewer NMs at around 2 months, these infants were becoming more constantly misaligned. Although constantly manifest by 4 months, the angle of deviation continued to increase until strabismus surgery on both infants was undertaken at around 9 months. Two further infants with similar characteristics have been observed in the infant vision laboratory in a group to be reported separately. One infant who needed frequent general anaesthetics was misaligned for 48 hours after each anaesthetic during her first year but at no other time and is now visually normal.

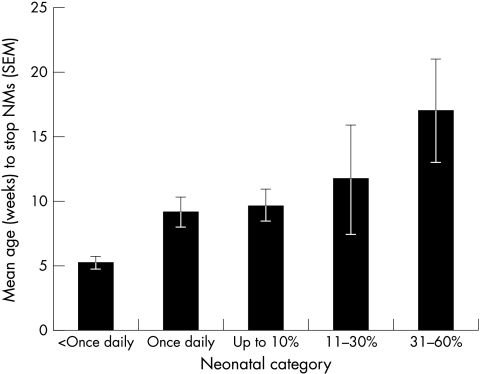

A one way ANOVA showed a highly significant effect of frequency of NMs on age at which NMs ceased (F5,205= 6.662, p <0.001). Those with most frequent NMs were later to cease squinting (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Mean age in weeks when neonatal misalignment (NMs) ceased by neonatal frequency category. More frequently misaligned infants were older when NMs ceased. Constant misalignments excluded because of unreliable data (see text).

Of the infants who squinted in the first month, 29.3% squinted momentarily, 59.6% for a few seconds, 8.8% for a few minutes, and 0.6% (two infants) for 10–60 minutes at a time (neither of whom later proved to be infantile esotropes). There was a weak, but significant, correlation between frequency and duration of misalignment when it occurred (Spearman’s rho: r2 = 0.18, p<0.01). Infants who squinted most frequently generally squinted for longer—for example, only 0.05% of infants who squinted only once daily did it for more than a few seconds, whereas 19% of those who squinted 11–30% of the time squinted for a few minutes. There were no sex differences in severity of any squint (t = 0.037, p = 0.7), age to start squinting (t = 0.2, p = 0.8), age at time of worst squinting (t = −0.93 p = 0.3), or age to stop squinting (t = 0.6, p = 0.5).

In week 1, 48.6% of NMs were unilateral (one eye fixing), 13.7% were bilateral (neither eye fixing the target) and 37.7% varied. There is a highly significant logarithmic trend (r2 = 0.95, p <0.001) for a rapid increase to unilaterality in the first month. Even if NMs are merely inappropriate convergence, the infants generally fix with one eye; 64% of the deviations freely alternated, 33% showed slight fixation preference, and only 3% were consistently in the same eye.

The vast majority (87.1%) of NMs were convergent, with a few (7.4%) showing both convergent and divergent deviations at different times. Only 5.2% were always divergent. Over the past 5 years, the orthoptist parents have been asked to estimate of the size of the deviation. Most report angles of >30Δ eso. Many parents of infants tested before this question was included enclosed photographs of their babies with similarly large angles.

At first, many NMs (30.7%) were not associated with any specific stimulus or behaviour. Later, attempting near fixation rapidly becomes the most common precipitating stimulus (53.8% at 3 months of age).

Many mothers commented on how surprised they had been at the size and frequency of the deviations, and their later complete resolution. Those reporting on second or third children commented on how one infant’s behaviour was often very different from that of earlier siblings.

Seventeen (7.9%) parents noticed transient nystagmus in the first 2 weeks, which subsequently resolved completely. This was usually jerky, intermittent, and on lateral gaze. Most of the mothers commented that it did not look like the end positional nystagmus commonly seen in older children, but occurred nearer to the primary position. No question had been asked about this on the questionnaire, the parents adding it as a spontaneous comment, so the true incidence cannot be established. Further details were unavailable. This appears to be the first time that this has been reported in normal neonates.

Relation to convergence

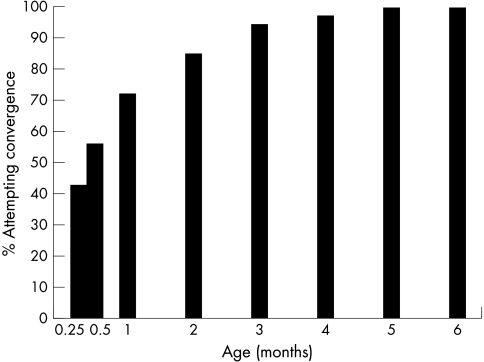

The mothers were asked when their infants first attempted reliable and repeatable convergence to near targets. This was similar to the “first vergence” assessed by Thorn et al,16,29 and did not specify a specific near point or quality of movement. The target was whatever the mothers found most successful, generally the mother’s face. Convergence was generally more delayed in most infants than was steady fixation or following, which were usually elicited by the second week of age; 42.9% attempted convergence in week 1, with the percentage rising logarithmically with age (r2 = 0.97) (Fig 3). By month 4, only four infants (2%) were still not seen to converge. There were no sex differences (t = −0.4, p = 0.6).

Figure 3.

Percentage of infants attempting convergence to a near target. Logarithmic increase in convergence responses in first 2 months of life (r2 = 0.97).

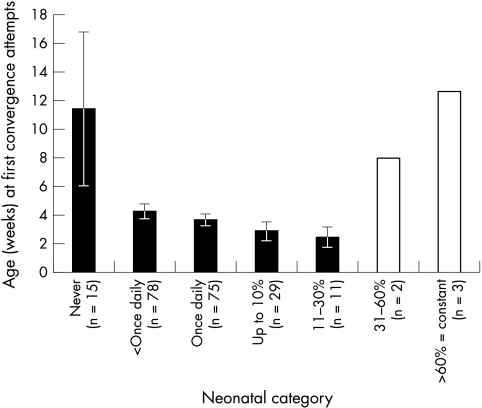

Figure 4 appears to illustrate that both frequent and rare NMs are associated with later first convergence. However, the data from the seven infants with NMs for >30% of the day (not shaded in Fig 4) have been excluded as unreliable. The wording of the question was “Is normal convergence attempted?” NMs are usually reported to occur at the time of attempted near fixation. An orthoptist could easily interpret very frequent NMs, which occurred on attempted near fixation, as “abnormal” convergence and so would answer “no” to the question. A “yes” response would only be used once NM had stopped when older. Secondly, if NMs occurred every time convergence was attempted, it is impossible to differentiate NM from attempted convergence. They would therefore answer “no” to the normal convergence question. These few children may not have been genuinely later to start to converge; indeed their frequent NMs might have been a sign of very early, but inaccurate, convergence.

Figure 4.

Neonatal frequency category versus age at first attempts at convergence. Unshaded columns denote very small numbers and equivocal responses excluded from main analysis (see text for discussion).

If these seven infants (3%) are excluded, one way ANOVA showed a significant effect of neonatal frequency group (F2.653, df 4,203, p = 0.03) with a highly significant linear trend (F7.79, df 1203, p=0.006) for the more frequently squinting infants (in the groups up to 30% of the time) to be earlier to converge.

This study can also clarify whether squinting precedes or follows first convergence. NM incidence increased slightly after week 1, whereas convergence often started slightly later. χ2 Analysis of whether the time of “worst NMs” preceded or followed first reports of convergence was highly significant (p=0.0002) with 43% of infants showing worst NMs before first convergence, 36% simultaneously, and only 20% showing most NMs after the first onset of convergence.

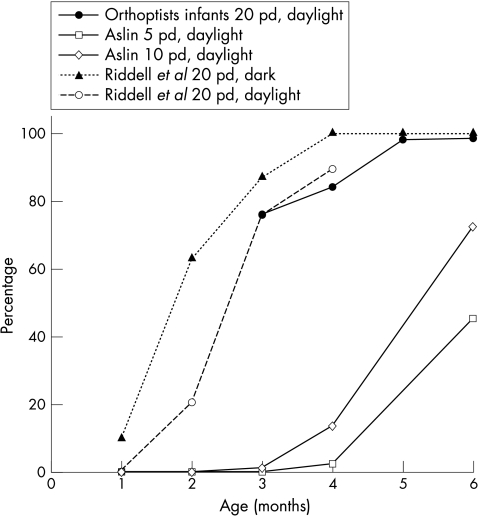

The 20Δ base out prism test was also used to investigate the onset of convergence. Responses from this group are combined with other published data19,30 in Figure 5. Responses here are almost identical to the data presented by Riddell et al.19 Using a 20Δ prism seemed to produce earlier vergence responses than those reported by others using smaller prisms.30,31 The similarity of these independent groups suggests that larger prisms are easier to overcome than smaller.

Figure 5.

Development of base out prism response. Orthoptists infants compared with published studies by Aslin (1977) and Riddell et al (1999). Permission granted for use of data by Elsevier Science.

It therefore appears likely that NMs represent a first sign of inaccurate attempts at convergence. The relation of NMs to later ocular abnormalities will be reported in the accompanying paper

DISCUSSION

The results of this follow-up observational study confirm that neonatal ocular misalignments are common and appear to be associated with the very early exercise of vergence. This study was able to follow the infants very closely, and reporting occurred at the time of observation. Fleeting NMs are more likely to have been spotted by the more expert and interested orthoptist observers, accounting for a lower incidence of “never seen to squint” than in the previously published cohort paper23 (26.8% compared to 44.8%).

Although eyecare professionals may look upon NMs as pathological, they are rarely seen as abnormal by those in primary health care. In a community setting, parents can be reassured that most normal infants will be growing out of NMs by 2 months and will have stopped altogether by 4 months. Referral should be arranged for any infant whose NM behaviour worsens after 2 months or who has an intermittent deviation after 4 months. Frequent NMs and truly never being misaligned may carry a small increased risk of later ocular problems (see companion paper), but most intermittently squinting neonates will progress to normal alignment, binocularity, and emmetropia.

If seen as part of a clinical paediatric ophthalmology caseload, it is not possible to differentiate frequent (but normal) NMs from an emerging infantile esotropia in an infant of less than 2 months of age. The importance of an accurate case history is emphasised because a (necessarily) brief outpatient examination may show a convergent deviation in a very young infant (especially when near fixation tasks that often elicit NMs are required of the infant) that is only intermittently present at home. The parents may report a “birth onset” squint and pathological esotropia may be erroneously diagnosed, but the infant eventually grows out of the deviation. This may account for at least some of the infants reported by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group.21,22 Frequent NMs and emerging infantile esotropia may be separate clinical entities with similar neonatal characteristics, or alternatively, a general predisposition for eso convergence errors in early infancy may “tip over” into true esotropia if binocular single vision development does not progress normally.

Change in frequency of NMs over the first 3 months of life may be a more important diagnostic clue than age of onset or time spent misaligned per se. Misalignments that are worsening at 2 months are likely to develop into infantile esotropia, while non-pathological NMs generally reduce from 1 month of age, but may still be seen until 3 months.

The orthoptists reported overwhelmingly large, intermittent esodeviations, not exodeviations as reported by Archer et al.32 It is improbable that these are pseudo-deviations because the angles are generally very large and orthoptists, unlike lay parents, are unlikely to be misled by epicanthus. If pseudo-strabismus were to be the cause of an apparent squint, the large angle lambda of early infancy,27,33 if anything, creates a significant bias towards pseudo-exotropia if corneal reflections are used to assess alignment.16,17

Convergence was reported from the very first weeks, earlier than previously reported by some authors,16,29 but not others.14,15,17 NMs appear to occur at or just before the time that convergence emerges and rapidly cease once vergence becomes reliable. If vergence develops early, infants are initially likely to spend more of their waking hours misaligned, but unless these misalignments are very frequent and worsening after the first month, they are less likely to go on to have a later abnormality (see companion paper).

NMs also appear to provide a useful research tool for the study of the emerging vergence system because they are large and easy to detect. The relation of NMs to accommodation measured objectively in a laboratory setting will be the subject of a future paper in preparation. In a clinical setting, awareness of what parents are describing when they say their babies’ eyes are “all over the place” or “unfocused” can help to differentiate pathology more accurately in the few, and avoid anxiety for many others.

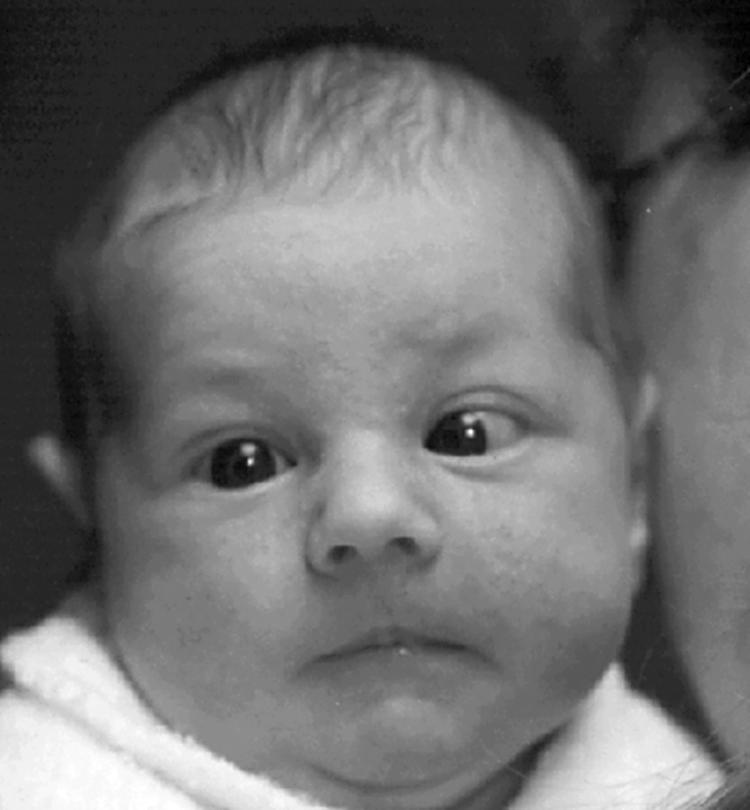

Figure 1.

Neonatal misalignments in a normal infant aged 5 weeks. These deviations were observed for a few seconds at a time for up to 10% of waking hours. They were reducing at 2 months and resolved by 3 months. She is now orthophoric and has normal binocular vision and acuity.

Footnotes

Angle lambda is the angle between the pupillary axis and the line of sight formed at the centre of the pupil. A positive angle lambda causes the corneal reflection to be nasal to the pupil centre. The terms angle alpha or angle kappa are often used synonymously and are almost identical.

“Squinting” and “NMs” denote ocular misalignment that may be unilateral or bilateral and may or may not be pathological. At this age it is not possible to differentiate those infants who will progress to show pathological strabismus from those who will subsequently develop normal binocular vision.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson J. The developing visual brain. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 2000.

- 2.Held R. Normal visual development and its deviations. In: Lenerstrand G, von Noorden G, Campos E, eds. Wenner Gren Symposium No 49. Stockholm: Macmillan, 1988:247–57.

- 3.Atkinson J, Braddick O, French J. Infant astigmatism: its disappearance with age. Vis Res 1980;20:891–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson J, Braddick O, Robier B, et al. Two infant vision screening programmes: prediction and prevention of strabismus and amblyopia from photo- and videorefractive screening. Eye 1996;10(Pt 2):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gwiazda J, Thorn F, Bauer J, et al. Emmetropisation and the progression of manifest refraction in children followed from infancy to puberty. Clin Vis Sci 1993;8:337–44. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gwiazda J, Thorn F. Development of refraction and strabismus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1998;9:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrlich D, Braddick O, Atkinson J, et al. Infant Emmetropization: longitudinal changes in refraction components from nine to twenty months of age. Optom Vis Sci 1997;74:822–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birch E. Stereopsis in infants and its developmental relation to visual acuity. In: Simons K, ed. Early visual development, normal and abnormal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993:224–36.

- 9.Birch E, Gwiazda J, Held R. The development of vergence does not account for the onset of stereopsis. Perception 1983;12:331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birch E, Gwiazda J, Held R. Stereoacity development for crossed and uncrossed disparities in human infants. Vis Res 1982;22:507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Held R, Birch E, Gwiazda J. Stereoacuity of human infants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1980;77:5572–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Held R. Two stages in the development of binocular vision and eye alignment. In: Simons K, ed. Early visual development, normal and abnormal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993:250–7.

- 13.Currie D, Manny R. The development of accommodation. Vis Res 1997;37:1525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hainline L, Riddell P, Grose Fifer J, et al. Development of accommodation and convergence in infancy. Behav Brain Res 1992;49:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner J, Horwood A, Houston S, et al. Development of the response AC/A ratio over the first year of life. Vis Res 2002;42):2521–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorn F, Gwiazda J, Cruz A, et al. The development of eye alignment, convergence, and sensory binocularity in young infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994;35:544–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hainline L, Riddell P. Binocular alignment and vergence in early infancy. Vis Res 1995;35:3229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horwood A. Maternal observations of ocular alignment in infants. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1993;30:100–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riddell P, Horwood A, Houston S, et al. The response to prism deviations in human infants. Curr Biol 1999;9:1050–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohner N, Phillips A, Ford K. Birth to five. London: Health Promotion England, 1999.

- 21.Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. The clinical spectrum of early onset esotropia: experience of the congenital esotropia observational study. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Spontaneous resolution of early onset esotropia: experience of the congenital esotropia observational study. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horwood A, Williams B. Does neonatal ocular misalignment predict later abnormality? Eye 2001;15:485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwood A. Preliminary results of observation of the development of eye movement control in babies. In: Tillson G, ed. Advances in amblyopia and strabismus. Proceedings of the VIIth International Orthoptic Congress, 1991. Nuremberg, Germany: Fahner-Verlag, 1991:11.

- 25.Slater A, Findlay J. The corneal reflection technique and the visual preference method: sources of error. J Exp Child Psychol 1975;20:240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slater A, Findlay J. Binocular fixation in the newborn baby. J Exp Child Psychol 1975;20:248–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riddell P, Hainline L, Abrahamov I. Calibration of the Hirschberg test in human infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994;35:538–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hainline L, Riddell P. Eye alignment and convergence in young infants. In: Vital-Durand F, Atkinson J, Braddick O, ed. Infant vision. Oxford: Oxford Science Publications, 1996:221–48.

- 29.Thorn F, Gwiazda J, Cruz A, et al. Eye alignment, sensory binocularity, and convergence in young infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992;33(supp):713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aslin R. Development of binocular fixation in human infants. J Exp Child Psychol 1977;23:133–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coakes R, Clothier C, Wilson A. Binocular reflexes in the first 6 months of life: preliminary results of normal infants. Child Care Health Devel 1979;5:405–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Archer S, Sondhi N, Helveston E. Strabismus in infancy. Ophthalmology 1989;96:133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slater A, Findlay J. The measurement of fixation position in the newborn baby. J Exp Child Psychol 1972;14:349–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]