Serpiginous choroidopathy is an insidious, relentlessly progressive, idiopathic inflammatory disease affecting the retinal pigment epithelium and inner choroid. Choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) is a well recognised late complication of serpiginous choroidopathy in 10–25% of affected patients.1 In all previously reported cases CNV was recognised at the time of or after the diagnosis of serpiginous choroidopathy was established.2–4 We report a patient presenting with CNV who subsequently developed clinical findings characteristic of serpiginous choroidopathy.

Case report

A 31 year old man presented with decreased vision in his right eye in July 1997. Examination revealed acuities of 20/40 right eye and 20/20 left eye with normal anterior segments. The right fundus showed subretinal fluid and haemorrhage adjacent to the disc (Fig 1A). The left eye showed an irregularity superior to the optic disc (Fig 1B). The vitreous and fundi were otherwise normal bilaterally. Fluorescein angiography (Fig 2A, B) revealed peripapillary choroidal neovascular membranes in both eyes that were treated with argon laser photocoagulation. In April 1998 and February 1999 the left eye required photocoagulation for recurrent peripapillary CNV. Evaluation for floaters in February 2000 revealed 1+ vitreous cells and new lesions in the left eye.

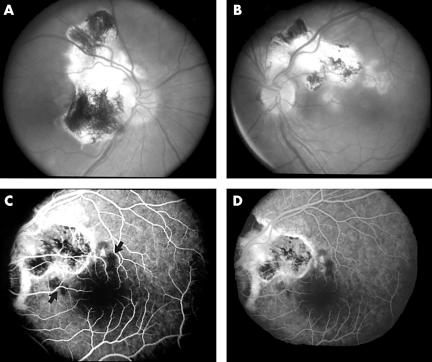

Figure 1.

July 1997. (A) The right eye shows subretinal fluid adjacent to the disc surrounded by subretinal haemorrhage extending to the fovea. (B) An undefined irregularity is noted superior to the optic disc of the left eye.

Figure 2.

(A) Angiography of the right eye reveals a wedge shaped peripapillary CNV membrane. (B) A smaller CNV membrane is present angiographically superior to the left optic disc (late phase).

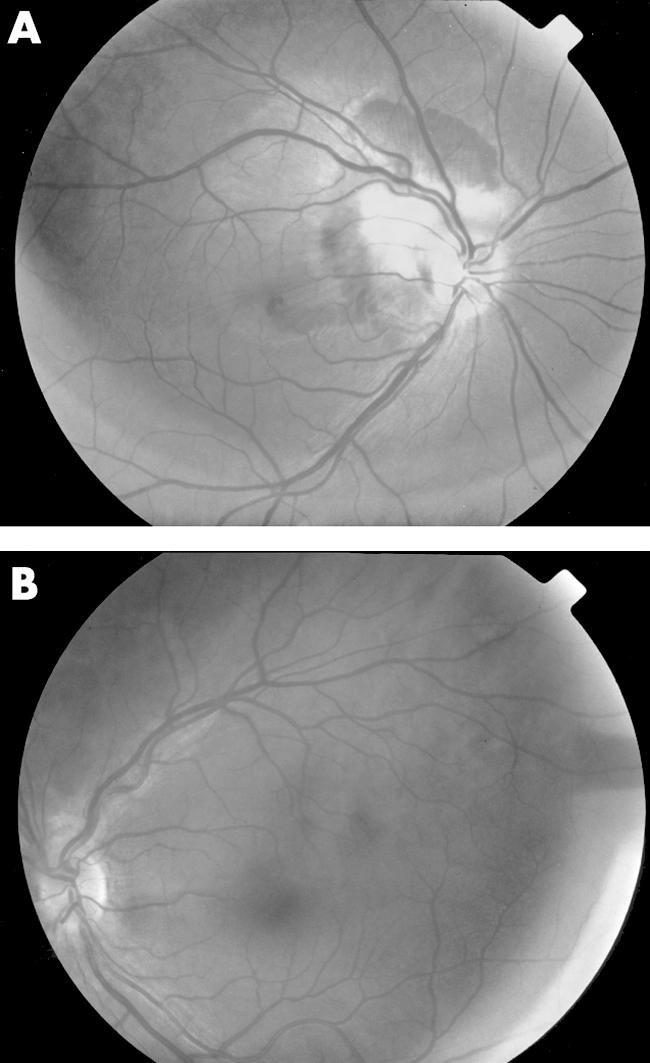

Examination at the National Eye Institute in April 2000 revealed acuities of 20/40 right eye and 20/16 left eye with normal anterior segments. The vitreous contained trace cells without haze bilaterally. The right fundus showed a large peripapillary chorioretinal scar. The left fundus revealed a chorioretinal scar superior to the disc and two yellow, irregularly circumscribed, deep macular lesions (Fig 3A, B). The retinal vessels and discs were normal and no subretinal fluid, haemorrhage, or macular oedema was noted in either eye.

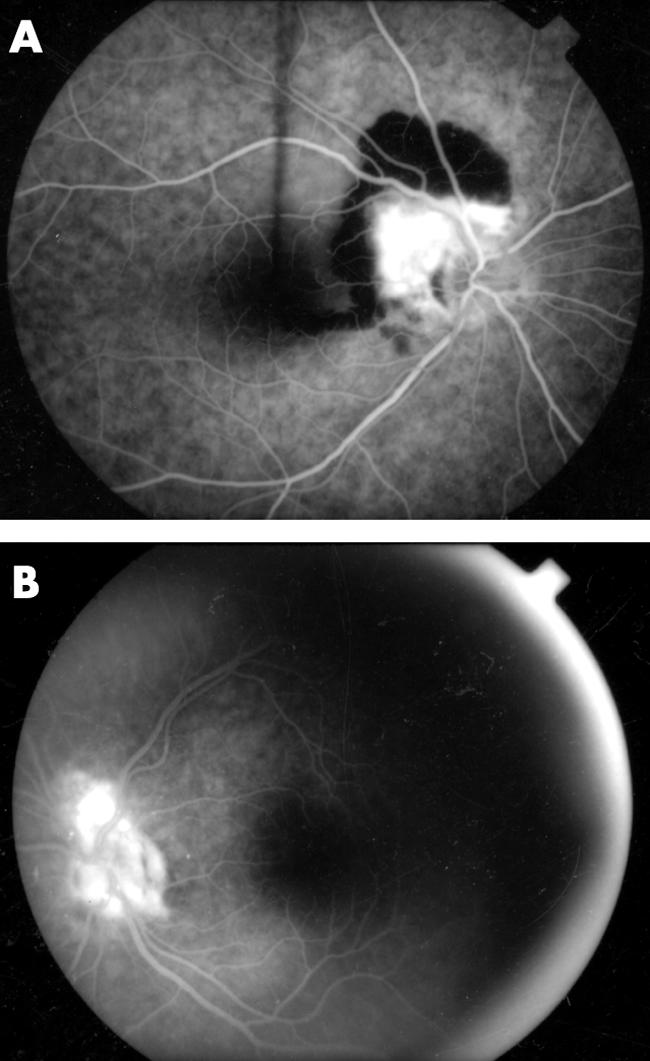

Figure 3.

April 2000. (A) The right eye shows a large peripapillary chorioretinal scar resulting from previous laser photocoagulation of the initial CNV lesion. (B) A similar photocoagulation scar is present in the left eye which also shows two non-contiguous active serpiginous lesions. The fluorescein angiogram of the left eye shows early hypofluorescence (C, arrows) corresponding to the locations of the active serpiginous lesions that later become hyperfluorescent (D).

Fluorescein angiography revealed early hypofluorescence and late hyperfluorescence corresponding to the macular lesions in the left eye (Fig 3C, D) with no evidence of CNV in either eye. Laboratory studies were non-diagnostic. A diagnosis of serpiginous choroidopathy was made based on the clinical and fluorescein characteristics of the macular lesions in the left eye.

Comment

CNV in serpiginous choroidopathy is associated with a poor visual prognosis.5 In a small study CNV was reported to develop within 16 months of the serpiginous diagnosis.3 In a larger retrospective study of 53 serpiginous patients active CNV was found in three patients at the time of initial diagnosis and in three others within 2–17 months.4 Our patient differs from those previously reported in that he was diagnosed and treated for idiopathic CNV before the recognition of clinical findings diagnostic of serpiginous choroidopathy. Other causes of posterior uveitis associated with CNV and chorioretinal lesions similar to those seen in our patient include acute posterior multifocal pigmented placoid epitheliopathy (APMPPE), presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS), sarcoidosis, multifocal choroiditis, birdshot chorioretinopathy, and toxoplasmosis. As with most cases of serpiginous choroidopathy, the CNV in these entities typically occurs late in the disease course.

The exact pathogenesis of idiopathic CNV is unknown. CNV in eyes with uveitis, however, is believed to develop in direct response to the intraocular inflammation which may alter the balance between vascular growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and inhibitors.1,6 In the early stages of development active serpiginous lesions and CNV may appear as poorly defined subretinal lesions difficult to differentiate by ophthalmoscopy. Typically with fluorescein angiography classic CNV and serpiginous lesions are readily distinguished as the former shows early hyperfluorescence while the latter characteristically shows early blockage. Occult CNV, which may show subtle or less pronounced early hyperfluorescence with late leakage, however, may be more difficult to distinguish from an early serpiginous lesion.

This case illustrates that serpiginous choroidopathy may present with CNV. In contrast to idiopathic CNV, optimal treatment of CNV in patients with uveitis may require immunosuppressive treatment that addresses the underling ocular inflammation with or without adjunctive laser therapy.1,6 Further investigation is needed to better define the role of emerging therapies for CNV such as photodynamic therapy which may offer promise for the treatment of CNV in uveitis patients.7

Financial support: none.

References

- 1.Kuo IC, Cunningham ET Jr. Ocular neovascularization in patients with uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2000;40:111–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jampol LM, Orth D, Daily MJ, et al. Subretinal neovascularization with geographic (serpiginous) choroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol 1979;88:683–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erkkila H, Laatikainen L. Subretinal and disc neovascularization in serpiginous choroiditis. Br J Ophthalmol 1982;66:326–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenkranz MS, Gass JD, Clarkson JG. Atypical serpiginous choroiditis. Arch Ophthalmol 1982;100:1773–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erkkila H, Laatikainen L. A follow up study of serpiginous choroiditis. Acta Ophthalmol 1981;59:707–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dees C, Arnold JJ, Forrester JV, et al. Immunosuppressive treatment of choroidal neovascularization associated with endogenous posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:1456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farah ME, Costa RA, Muccioli C, et al. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;124:137–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]