Posterior polar cataracts are relatively uncommon yet they pose a significant challenge to the cataract surgeon. Cataract surgery in these cases is frequently accompanied by a high incidence of posterior capsule rupture (PCR).

Morphology

Posterior polar cataracts are associated with remnants of the hyaloid system or the tunica vasculosa lentis.1 These cataracts may also occur without any relation to hyaloid remnants and appear as circular or rosette shaped opacities; they are hereditary and usually transmitted as a dominant trait. The gene for this has been mapped to chromosome 16q22.2

Classification3

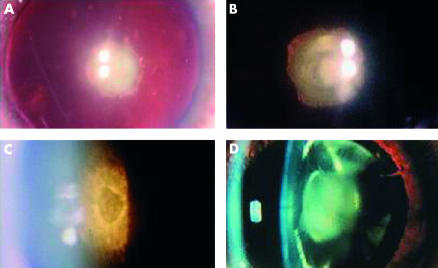

See Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Classification of posterior polar cataracts

| Type 1 | Opacity associated with posterior subcapsular cataract. |

| Type 2 | Opacity with ringed appearance like an onion. |

| Type 3 | Opacity with dense white spots at the edge often associated with thin or absent posterior capsule. |

| Type 4 | Combination of the above 3 types with nuclear sclerosis. |

Figure 1.

(A) One spot polar cataract. (B) Onion polar cataract. (C) Polar cataract with hole in posterior capsule. (D) Polar cataract with nuclear sclerosis.

Methods

The incidence of posterior polar cataracts in our centre is approximately 5 per 1000. We conducted a retrospective review from 1994 to 1999 and identified 31 patients (36 eyes) who had surgery for posterior polar cataracts.

Results

Four eyes had PCR (11.1%) and the other 32 had uncomplicated surgery; 34 eyes achieved a best corrected visual acuity of 6/12 or better (94.4%).

Comment

Our series showed a PCR rate of 11.1% in contrast with the 26% incidence reported by Osher et al4 and 36% by Vasavada and Singh.5 No hydrodissection was attempted and only careful controlled hydrodelineation was performed. This was done using small aliquots of balance salt solution (BSS) to loosen the nucleus while simultaneously watching the capsular bag to ensure that the fluid wave passed gently. In some cases, no hydroprocedures were necessary as there was slow separation of the nucleus by the BSS flowing from the phaco tip.

Vasavada and Singh described the use of step by step chop in situ and lateral separation to minimise stress on the capsule-zonule complex.6,7 We preferred the use of the “lambda” technique which involved sculpting in the shape of the Greek letter (λ), followed by cracking along both “arms” and removal of the central piece first. The advantage of this is its gentleness in not stretching the capsule while removing the quadrants, especially the first one. We emphasise that this is our preferred technique and other techniques would be equally effective in skilled hands.

We also used low vacuum, low aspiration, and low inflow parameters to ensure a more stable anterior chamber; bottle height was at 50 cm, vacuum at 100 mm Hg, and aspiration flow rate at 20 ml per minute. Optimum power setting was achieved when minimal movement of the nucleus occurred while sculpting.

The epinucleus and cortex were removed using manual dry aspiration with Simcoe cannula. This method is gentler as we believe that the aspiration pressure is more controllable with our “million dollar” hands. There is also no “after aspiration” effect which in the automated unit can continue for several milliseconds even after the foot has been taken off the pedal. The disadvantage of manual aspiration is the increased surgical time.

The status of the posterior capsule (PC) dictated the action of the surgeon. If the PC was absent or torn but with no vitreous loss, a dispersive viscoelastic was injected over the defect to tamponade and push the vitreous face backwards. A dispersive rather than a cohesive viscoelastic is preferable as it is more adapted to maintaining a space and stabilising the anterior vitreous face. If there was PCR with vitreous loss, a two port anterior vitrectomy was performed. Intraocular lens implantation in these cases would depend on the extent of the PCR and the integrity of the remaining PC.

Surgical management of posterior polar cataracts poses a special challenge to the cataract surgeon. It is important that the surgeon and the patient understand the technical difficulties associated and are aware of potential complications. It may be prudent to address these cases at the end of an operating list or to shorten the list in anticipation of prolonged surgical time. The surgeon should use a technique that he or she is most familiar and comfortable with. With emphasis on gentleness, together with patience and a well practised technique, the incidence of PCR can be minimised in phacoemulsification for posterior polar cataracts.

References

- 1.Luntz MH. Clinical types of cataracts. Duane’s Ophthalmology 1996; CD ROM.

- 2.Maumenee III. Classification of hereditary cataracts in children by linkage analysis. Ophthalmology 1979;86:1554–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anon. Consultation section: Cataract surgical problem. J Cataract Refract Surg 1997;23:819–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osher RH, Yu BC, Koch DD. Posterior polar cataracts: a predisposition to intraoperative posterior capsular rupture. J Cataract Refract Surg 1990;16:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasavada A, Singh R. Phacoemulsification in eyes with posterior polar cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasavada A, Singh R. Step-by-step chop in-situ and separation of very dense cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998;24:156–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasavada A, Singh R. Surgical techniques for difficult cataracts. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1999;10:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]