Abstract

Aims: To report the safety and visual outcome data of external beam irradiation for recurrent choroidal neovascularisation complicating age related macular degeneration.

Methods: Eighteen consecutive eyes received external beam irradiation with seven fractions of 2 Gy (total dose 14 Gy). The next 16 consecutive eyes received external beam irradiation with five fractions of 3 Gy (total dose 15 Gy). Main outcome measure was change in visual acuity. Secondary outcome variables were contrast sensitivity and fundus photographic/fluorescein angiographic progression.

Results: The 3 Gy fraction group lost fewer lines of distance visual acuity at the three and six month follow up. At one year follow up, this difference was not maintained with 2 Gy fraction and 3 Gy fraction eyes. At one year follow up a decrease in visual acuity of three or more lines (moderate visual loss) occurred in 58% of 2 Gy and 42% of 3 Gy fraction eyes (p<0.36). At one year follow up a decrease in visual acuity of six or more lines (severe visual loss) occurred in 41% of 2 Gy eyes and 17% of 3 Gy eyes (p<0.23). At three months follow up, 3 Gy eyes were less likely (0%) than 2 Gy eyes (47%) to show moderate visual loss (p<0.003). However, Kaplan Meier curves estimate a significantly lower rate of severe visual loss in the 3 Gy group (p = 0.02). There were no significant differences in contrast sensitivity loss or fluorescein angiographic stabilisation rates. No evidence of radiation toxicity was observed.

Conclusion: Our results are consistent with trends for a palliative benefit with higher fraction sizes and doses. The radiobiologic differences between low and high fraction size groups in this study are modest and correlate with the modest and short term difference in visual outcomes. These trends support further investigation of radiotherapy using fraction sizes of 4 Gy or higher.

Keywords: choroidal neovascularisation, age related macular degeneration, radiotherapy, external beam irradiation

The Macular Photocoagulation Study (MPS) has shown the efficacy of thermal laser photocoagulation for patients with extrafoveal or juxtafoveal classic choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) complicating age related macular degeneration (ARMD). Whereas the benefit of laser photocoagulation over observation for non-foveal classic CNV has been shown, many patients lose central visual acuity despite laser therapy.1,2 Severe visual loss in laser treated eyes is associated with recurrence of CNV.1–3

Recurrent CNV is a significant cause of failure after laser photocoagulation.4–7 Subfoveal laser photocoagulation remains controversial as treatment often causes immediate visual loss despite its long term benefit over observation, and MPS guidelines for laser photocoagulation are applicable only to a minority of patients. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin has been shown to be beneficial for treating classic or predominantly classic subfoveal CNV complicating ARMD8 and somewhat beneficial for subfoveal occult CNV.9 Although the trials investigating photodynamic therapy were not designed to evaluate treatment efficacy for a smaller subgroup with recurrent subfoveal CNV, visual acuity loss rates did not differ between photodynamic treated and observed eyes with recurrent CNV.8 In addition, a pilot study suggests no reason to prefer submacular surgery over laser photocoagulation for eyes with subfoveal recurrent CNV.10

Thus, additional treatments for recurrent subfoveal CNV require investigation. One such potential treatment is radiation. Most clinical studies have employed external beam irradiation using standard fractions of approximately 2 Gy to a total of 10–20 Gy for new subfoveal CNV. Some uncontrolled, non-randomised studies report minimal or no therapeutic external beam irradiation effect,11–13 whereas others report a moderate benefit with standard fractions.14–17 Higher fractions and doses of external beam irradiation18 and other modalities such as brachytherapy17,19 or proton beam irradiation20,21 have also been examined. Some evidence of angiographic regression of CNV has been observed with higher fractions, especially after proton beam irradiation, but radiation retinopathy rates are significant.21

The eight well controlled, randomised published studies available to date, comparing radiation with observation indicate that higher non-standard fractions22–29 may be beneficial. These randomised, controlled studies investigated radiotherapy for new subfoveal CNV, but did not include eyes with recurrent CNV.

We performed a non-randomised, uncontrolled study of external beam irradiation for recurrent subfoveal CNV complicating ARMD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty four patients with ARMD and recurrent subfoveal (classic and/or occult) CNV after previous laser photocoagulation were eligible for inclusion in this non-randomised dose escalation study. Patients were enrolled in the study from March 1995 to May 1999.

Best corrected distance visual acuity was recorded on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study chart (ETDRS). Phakic patients were assessed in the study and non-study eye for extent of nuclear sclerosis, cortical cataract, and posterior cataract using a subjective 0–4 grading system. Contrast threshold for large letters was measured at a distance of 1 m by using the Pelli-Robson chart. Colour stereo photography and fluorescein angiography was performed.

Medical history included age, sex, hypertension or on antihypertensive (yes, no), smoking status (no, quit, currently), aspirin or coumadin intake (yes, no), and vitamin intake (yes, no). Follow up evaluations were performed at 3, 6, 12, 24 and 52 weeks after enrollment, and planned at one year intervals thereafter for four years. This report emphasises the results at one year.

Radiation planning and treatment

Patients underwent conventional simulation followed by CT localisation or by a CT-simulator in preparation for use of a small treatment port, as described previously.29 Seven fractions of 2 Gy (total 14 Gy) or five fractions of 3 Gy (total 15 Gy) were administered over seven or five consecutive business days, respectively. Treatment was prescribed to the 90% isodose line.

Clinical vision measures

The primary outcome variable measured at each examination was distance visual acuity (DVA). Secondary outcome variables were contrast sensitivity (CS) and angiographic/photographic appearance. DVA at each time point was analysed for group differences using Wilcoxon rank sums test. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to test the difference between the treatment groups (2 Gy fraction versus 3 Gy fraction) for the decrease in DVA across the entire study time frame. Contrast sensitivity values were recorded from the Pelli-Robson chart as the base-10 log of CS.

Angiographic and photographic grading

Fluorescein angiograms and colour photographs were reviewed and graded in a masked manner with respect to treatment group. Fluorescein characteristics were graded for CNV size, CNV characteristics (Table 1), number of previous laser treatments for CNV, eligibility for laser according to MPS guidelines (yes, no), foveal involvement of previous laser scar (yes, no), and laser scar (MPS disc area) by the Scheie Eye Institute reading centre in a masked fashion.

Table 1.

Fluorescein angiography grading

| Parameter | Grade |

| CNV characteristic | Classic, alone |

| Predominantly classic | |

| Minimally classic | |

| Occult, alone | |

| CNV size | ⩽1MPS DA |

| >1–⩽2 MPS DA | |

| >2–⩽3.5 MPS DA | |

| >3.5–⩽4 MPS DA | |

| >4–⩽6 MPS DA | |

| >6–⩽9 MPS DA | |

| >9 MPS DA | |

| CNV size+laser scar | ⩽1 MPS DA |

| >1–⩽2 MPS DA | |

| >2–⩽3.5 MPS DA | |

| >3.5–⩽4 MPS DA | |

| >4–⩽6 MPS DA | |

| >6–⩽9 MPS DA | |

| >9 MPS DA | |

| CNV+blood+EBF+SPED | ⩽1MPS DA |

| >1–⩽2 MPS DA | |

| >2–⩽3.5 MPS DA | |

| >3.5–⩽4 MPS DA | |

| >4–⩽6 MPS DA | |

| >6–⩽9 MPS DA | |

| >9 MPS DA | |

| Classic CNV size | ⩽1MPS DA |

| >1–⩽2 MPS DA | |

| >2–⩽3.5 MPS DA | |

| >3.5–⩽4 MPS DA | |

| >4–⩽6 MPS DA | |

| >6–⩽9 MPS DA | |

| >9 MPS DA | |

| Subretinal haemorrhage | None |

| ⩽25% of clinical macula | |

| >25% of clinical macula | |

| 100% of clinical macula (arcade to arcade) | |

| Subretinal fibrosis | ⩽25% of clinical macula |

| >25% of clinical macula | |

| 100% of clinical macula (arcade to arcade) |

CNV, choirodal neovascularisation; EBF, elevated blocked fluorescence; SPED, serous pigment epithelial detachment.

For overall grading of follow up angiograms and photographs, when there was an increase in size of the membrane and/or increase in haemorrhage or subretinal fluid from baseline, the membrane was graded as worsened. When there was no change in the size of the membrane without increased haemorrhage or subretinal fluid, the membrane was graded as stable. When there was a decrease in the degree of leakage or membrane size with improvement in haemorrhage or subretinal fluid, the membrane was graded as improved.

Statistical methods

Categorical data were analysed using χ2 unless the cells sizes were too small and then Fisher’s exact tests were used. Outcomes analysed by Kaplan-Meier analysis were “time to failure” which were different from “distribution of changes from baseline at this time”. Thus, for Kaplan-Meier analysis, follow up data include data greater than one year follow up. Changes in DVA from baseline were analysed using t tests if there were two groups tested or analysis of variance (ANOVA) if there were more than two groups or when testing for possible contributing factors. For contrast sensitivity, treatment differences in log CS were analysed using t tests. Percent contrast is reported which is the reciprocal of CS.

In May 1999 a decision was made to stop enrolment into the trial and continue follow up. One year follow up data are reported, as decreased follow up compliance occurred after one year.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Eighteen consecutive eyes (2 Gy fraction group) (“low dose” group) received external beam irradiation with seven fractions of 2 Gy (total dose 14 Gy). The next 16 consecutive eyes (3 Gy fraction group) (“high dose” group) received external beam irradiation with five fractions of 3 Gy (total dose 15 Gy). The distributions of baseline factors are outlined in Table 2 and were examined for differences between the groups. Variables were similarly distributed between the two groups. However, patients randomised to 3 Gy fraction group showed a lower proportion of hypertensives.

Table 2.

Demographic and baseline data

| Study group | |||

| Low dose (n = 18) | High dose (n = 16) | p Value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 (44) | 3 (19) | 0.11, χ2 |

| Female | 10 (56) | 13 (81) | |

| Age | |||

| ⩽65 | 0 | 0 | 0.89, t test |

| 66–75 | 4 | 5 | |

| 76–85 | 13 | 11 | |

| ⩾86 | 1 | 0 | |

| Mean | 77 | 78 | |

| Visual acuity | |||

| ⩾20/64 | 6 (33) | 0 (0) | 0.19, Wilcoxon rank sum |

| 20/125–20/80 | 4 (22) | 9 (56) | |

| 20/250–20/160 | 3 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| ⩽20/320 | 5 (28) | 6 (38) | |

| Median | 20/100 | 20/125 | |

| CNV type | |||

| Classic only | 7 (41) | 6 (38) | 0.81, Fisher’s |

| Occult only | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | |

| Predominantly classic | 3 (18) | 3 (19) | |

| Minimally classic | 4 (24) | 6 (38) | |

| Unknown | 1 (6) | 1(6) | |

| Size: total lesion | |||

| ⩽1 | 4 (22) | 5 (31) | 0.86, Fisher’s |

| >1 to ⩽2 | 2 (11) | 3(19) | |

| >2 to ⩽3.5 | 5 (28) | 5(31) | |

| >3.5 to ⩽4 | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| >4 to ⩽6 | 2 (11) | 1(6) | |

| >6 to ⩽9 | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| >9 | 2 (11) | 1(6) | |

| Unable to grade | 0 (0) | 1(6) | |

| Size: total area plus laser scar | |||

| ⩽1 | 0 (0) | 3 (19) | 0.47, Fisher’s |

| >1 to ⩽2 | 2 (11) | 2 (13) | |

| >2 to ⩽3.5 | 5 (28) | 2 (13) | |

| >3.5 to ⩽4 | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| >4 to ⩽6 | 4 (22) | 5 (32) | |

| >6 to ⩽9 | 3 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| >9 | 3 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| Unable to grade | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| Size: area of CNV | |||

| ⩽1 | 4 (22) | 5 (31) | 0.89, Fisher’s |

| >1 to ⩽2 | 5 (28) | 5(31) | |

| >2 to ⩽3.5 | 2 (11) | 3 (19) | |

| >3.5 to ⩽4 | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| >4 to ⩽6 | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | |

| >6 to ⩽9 | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| >9 | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | |

| Unable to grade | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | |

| Size: area of classic CNV | |||

| No classic | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.43, Fisher’s |

| ⩽1 | 5 (28) | 9 (56) | |

| >1 to ⩽2 | 6 (33) | 3(19) | |

| >2 to ⩽3.5 | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | |

| >3.5 to ⩽4 | 3 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| >4 to ⩽6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| >6 to ⩽9 | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| >9 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Unable to grade | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | |

| MPS eligible | |||

| No | 13 (72) | 13(81) | 0.41, Fisher’s |

| Yes | 5 (13) | 2 (13) | |

| Unable to grade | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| Number of previous lasers | 0.6, Fisher’s | ||

| One | 11 (61) | 11 (69) | |

| Two | 5 (28) | 2 (12) | |

| Three | 2 (11) | 3 (19) | |

| Contralateral eye | 0.69, χ2 | ||

| Wet | 9 (53) | 9 (60) | |

| Dry | 8 (47) | 6 (40) | |

| Disciform scar: contralateral eye | 0.23, χ2 | ||

| Yes | 5 (28) | 8 (50) | |

| No | 13 (72) | 8 (50) | |

| Hypertensive | 0.08, χ2 | ||

| Yes | 11 (61) | 5 (31) | |

| No | 7 (39) | 11 (69) | |

| Smoking status | 0.16, Fisher’s | ||

| Currently smoking | 4 (22) | 0 (0) | |

| Quit smoking | 6 (33) | 6 (38) | |

| Never smoked | 8 (44) | 10 (62) | |

| Taking ASA or coumadin | 0.93, χ2 | ||

| Yes | 11 (61) | 10 (62) | |

| No | 7 (39) | 6 (38) | |

| Taking vitamins | 0.33, χ2 | ||

| Yes | 13 (72) | 9 (56) | |

| No | 5 (28) | 7 (44) | |

Numbers in columns are n (%) unless otherwise stated

Visual function outcomes and follow up

The number of eyes followed up for specific periods is included in Table 3. The visual acuity distributions for patients after enrolment are outlined in Table 3. The mean distance visual acuity in the 2 Gy fraction group decreased from 20/100 at baseline to 20/400 at one year follow up. The mean distance visual acuity in the 3 Gy fraction group decreased from 20/125 at baseline to 20/320 at one year follow up. There were no statistically significant differences for mean visual acuity between the two groups at any follow up period (Table 3).

Table 3.

Visual acuity distribution by time and dose

| Follow up, study group | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 3 weeks | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

| Low (n = 18) | High (n = 16) | Low (n = 18) | High (n = 15) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 13) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 16) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 11) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 12) | |

| ⩾20/64 | 6 (33) | 0 (0) | 6 (33) | 1 (7) | 2 (12) | 1 (8) | 3 (18) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 1 (9) | 2 (12) | 1 (8) |

| 20/125 to 20/80 | 4 (22) | 9 (56) | 4 (22) | 7 (47) | 2 (12) | 5 (38) | 2 (12) | 8 (50) | 3 (18) | 2 (18) | 1 (6) | 1 (8) |

| 20/250 to 20/160 | 3 (17) | 1 (6) | 2 (11) | 2 (13) | 7 (41) | 1 (8) | 4 (24) | 2 (12) | 2 (12) | 2 (18) | 2 (12) | 1 (8) |

| ⩽20/320 | 5 (28) | 6 (38) | 6 (33) | 5 (33) | 6 (35) | 6 (46) | 8 (47) | 6 (38) | 10 (59) | 6 (55) | 12 (71) | 9 (75) |

| Median | 20/100 | 20/125 | 20/125 | 20/125 | 20/200 | 20/160 | 20/200 | 20/160 | 20/400 | 20/320 | 20/400 | 20/320 |

| p Value Wilcoxon | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.95 | 0.41 | 0.62 | 0.67 | ||||||

The distribution of change in distance visual acuity from the initial visit is outlined in Table 4. At three and six months there was a statistically significant difference in changes in distance visual acuity from baseline between the two groups as the 3 Gy fraction group lost less lines of distance visual acuity. At one year follow up, this difference was not maintained with 2 Gy fraction and 3 Gy fraction eyes losing a mean of 3.6 and 3.1 lines of distance visual acuity, respectively (Table 4, Fig 1). Possible contributing factors at baseline were analysed by ANOVA for effect on visual acuity outcomes and were found not to effect visual acuity changes at one year (data not shown).

Table 4.

Visual acuity change from baseline by time and treatment

| Follow up | Follow up, study group | |||||||||

| 3 weeks | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 6 months | 12 months | ||||||

| Low (n = 18) | High (n = 15) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 13) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 16) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 11) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 12) | |

| ⩽1 line loss | 15 (83) | 13 (87) | 10 (59) | 12 (92) | 8 (47) | 15 (94) | 7 (41) | 9 (82) | 6 (35) | 5 (42) |

| 2 or 3 lines lost | 2 (11) | 2 (13) | 6 (35) | 1 (8) | 7 (41) | 1 (6) | 5 (29) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 2 (17) |

| 4 or 5 lines lost | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) | 3 (18) | 3 (25) |

| ⩾6 lines lost | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 5 (29) | 0 (0) | 6 (35) | 2 (17) |

| Mean | −0.39 | 0.07 | −1.12 | 0 | −2.76 | 0 | −2.85 | −0.36 | −3.56 | −3.08 |

| p Value Wilcoxon | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.48 | |||||

Figure 1.

Line graph showing the number of lines of distance visual acuity loss over time for the low and high dose groups.

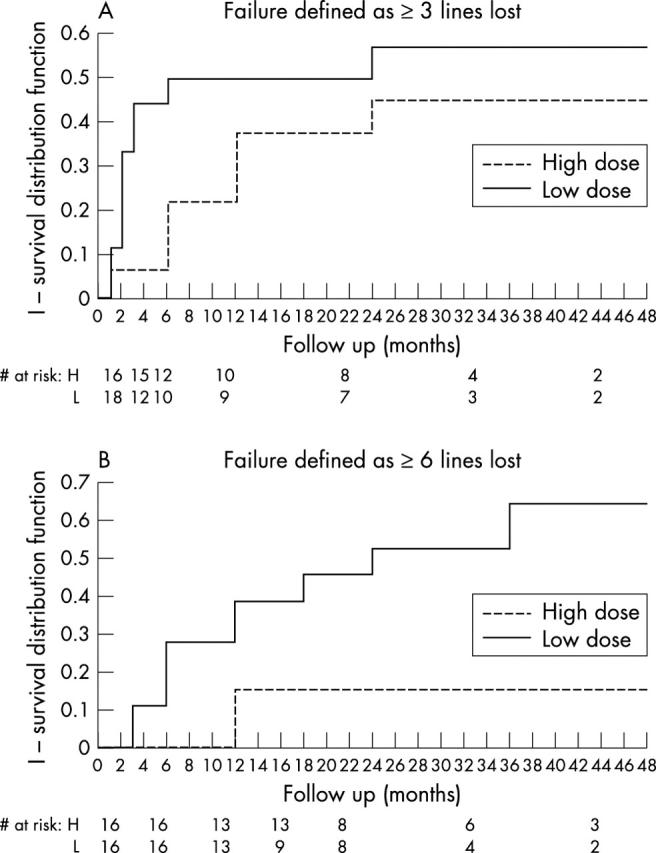

At the same one year follow up, a decrease in visual acuity of three or more lines (moderate visual loss) occurred in 10 of 17 (58%) 2 Gy fraction eyes and in five of 12 (42%) 3 Gy fraction eyes (p<0.36). At one year follow up, a decrease in visual acuity of six or more lines (severe visual loss) occurred in seven of 17 (41%) 2 Gy eyes and in two of 12 (17%) 3 Gy eyes (p<0.23). There were no statistically significant differences in the development of moderate or severe visual loss between the two groups at any follow up period except at three months where 3 Gy eyes were less likely (0%) than 2 Gy eyes (47%) to show moderate visual loss (p<0.003). However, Kaplan Meier curves estimated a significantly lower rate of severe visual loss in the 3 Gy group (p = 0.02) (Fig 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing proportion of eyes with (A) three or more and (B) six or more lines of visual acuity loss over time for the low and high dose groups.

The contrast threshold was compared between the two groups (Table 5, Fig 3). There were no statistically significant differences in the development of severe contrast loss between the two groups at any follow up period.

Table 5.

Contrast sensitivity threshold by time and treatment

| Follow up, study group | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 3 weeks | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 6 months | 12 months | |||||||

| Low (n = 16) | High (n = 16) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 15) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 13) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 16) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 12) | Low (n = 17) | High (n = 13) | |

| ⩽10% | 5 (31) | 5 (31) | 5 (29) | 6 (40) | 5 (29) | 4 (31) | 4 (24) | 8 (50) | 3 (18) | 4 (33) | 2 (12) | 4 (31) |

| 11% to 49% | 8 (50) | 9 (56) | 9 (53) | 7 (47) | 8 (47) | 8 (62) | 7 (41) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (59) | 5 (42) | 6 (35) | 5 (38) |

| ⩾50% | 3 (19) | 2 (13) | 3 (18) | 2 (13) | 4 (24) | 1 (8) | 6 (35) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (23) | 3 (25) | 9 (53) | 4 (31) |

| p Value (t test) | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.2 | ||||||

Figure 3.

Line graph showing the change in contrast sensitivity over time for the low and high dose groups.

Fluorescein angiography and fundus photography

Fluorescein angiography was performed at all visits for 15 of 18 and for 10 of 16 patients in the 2 and 3 Gy fraction groups, respectively. Fluorescein angiography was performed at baseline and at the one year visit for 16 of 18 patients and for 13 of 16 patients in the 2 and 3 Gy fraction groups, respectively. Two and 3 Gy fraction groups did not differ at baseline with regard to various fluorescein angiographic features (Table 2). For 2 and 3 Gy fraction groups, the one year follow up visual acuity line loss rates were not statistically different for eyes with classic, mixed, or occult CNV or laser eligible CNV at baseline (data not shown).

Choroidal neovascularisation characteristics (Table 1) at baseline did not influence visual acuity loss rates (data not shown). CNV growth rates did not differ between the 2 and 3 Gy groups. The 2 and 3 Gy groups at one year showed a mean increase in CNV size of 1.2 and 2.4 disc diameter categories, respectively (p<0.28), a mean increase in CNV size+all of 0.9 and 2.5 disc diameter categories, respectively (p<0.08), and a mean increase in classic CNV size of 2.2 and 1.7 disc diameter categories, respectively (p<0.69). For both groups, the presence or absence of blood or fibrosis at baseline did not influence visual acuity loss rates (data not shown).

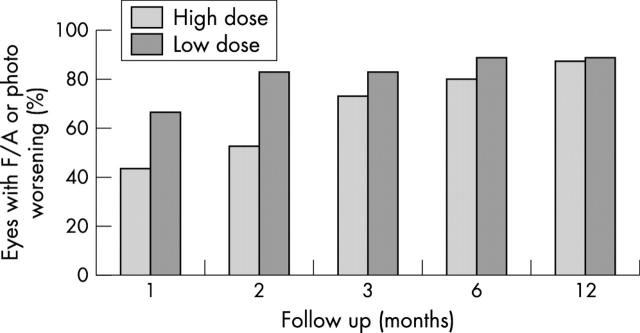

At one year follow up, the 2 and 3 Gy groups were graded overall as worsened by fluorescein angiography and/or fundus photography for 16 of 18 and 13 of 15 eyes respectively; no statistically significant differences in fluorescein angiographic and/or fundus photographic deterioration across time were found (p<0.167) (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Bar graph showing percentage of eyes with angiographic and/or photographic worsening at different time points for each group.

Complications

No evidence of acute or subacute radiation toxicity was observed. Radiation optic neuropathy or retinopathy was not observed in either group.

Cataract progression was defined as the clinical grade (0–4) increasing by one or more grade at one year from baseline for nuclear sclerosis (NS), cortical changes (CS), and posterior subcapsular cataract. At one year follow up, there were no differences in the rate of cataract progression between 2 and 3 Gy fraction groups for NS, CS, and PSC (Fisher’s exact two tail test, p<1.000, 1.000, 1.000, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The results of our non-randomised, uncontrolled dose escalation study indicate a modest and short term reduction in the rate of visual loss for eyes receiving 3 Gy fractions. The 3 Gy fraction group lost fewer lines of visual acuity than the 2 Gy fraction group at the three and six month follow up periods. This difference was not maintained at one year follow up. We found no evidence of fluorescein angiographic stabilisation of CNV for either group. Significant radiation-induced complications were not observed.

Our data represent the largest reported series of eyes with recurrent CNV and age related macular degeneration undergoing radiotherapy. Review of the literature concerning radiotherapy for recurrent CNV found no controlled studies and indicates limited evidence for a treatment benefit with standard fraction sizes and a possible benefit with non-standard fraction sizes.

In the largest case series reported previously, Finger et al17 used external beam irradiation (12–15 Gy in fractions of 1.8 Gy) and palladium 103 plaque brachytherapy in 22 and two recurrent CNV eyes, respectively. Fifty eight percent of eyes showed ophthalmoscopic/angiographic stabilisation or improvement. Forty two percent of eyes, however, lost two or more lines of visual acuity.17 Finger et al19 later used palladium 103 brachytherapy (dose range of 14–18 Gy) to treat six eyes with recurrent CNV. All six eyes remained within three lines of baseline visual acuity; two of the six eyes showed improved visual acuity. Ophthalmoscopic/angiographic appearance was reported to improve in five eyes and stabilised in one eye.19 Chakravarthy et al14 treated two eyes with recurrent subfoveal CNV with the same dose (external beam irradiation with five fractions of 3 Gy) as our high dose group and three eyes with five fractions of 2 Gy. In eyes receiving 3 Gy fractions, visual acuity improved in one eye and worsened in one eye. In eyes receiving 2 Gy fractions, visual acuity was unchanged in one eye and worsened in two eyes.14 Holz et al30 used stereotactic radiotherapy (eight fractions of 2 Gy) for six eyes with recurrent CNV. Visual acuity worsened in five eyes and improved in one eye. Proton beam irradiation (one fraction of 8 or 14 Gy) was used in two eyes with recurrent CNV.21 Visual acuity in the 8 Gy eye decreased from 20/500 to 20/1600, whereas acuity improved from 20/100 to 20/40 in the 14 Gy eye.21 Finally, 1515 and 1831 eyes with recurrent CNV have been treated with standard 2 Gy fractions, but data are not interpretable due to the nature of these reports.

Our results for treated recurrent subfoveal CNV are also consistent with information obtained from the eight published, randomised radiotherapy trials for new subfoveal CNV22–29 indicating a palliative beneficial effect with higher total doses22,29 and especially with higher fraction sizes.22,23,25

Post-laser recurrent CNV has a very poor visual outcome with (thermal laser, PDT, or submacular surgery) or without treatment. Interpretation of, or clinical recommendations from our radiation study or from the mixed results of the randomised radiation studies22–29 is limited. Our study has a small sample size and no control group. In addition, radiotherapy outcomes for recurrent CNV do not necessarily correlate with those for new subfoveal CNV. Despite these limitations, our results are consistent with trends for a palliative benefit with higher fraction sizes and doses. The radiobiologic differences between our low and high fraction size groups are modest and correlate with the modest and short term difference in visual outcomes. These trends support further investigation of radiotherapy using fraction sizes of 4 Gy or higher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank June Benson and Diane Leibach for their technical expertise. The authors thank Kevin Thompson, MD and Brad Wall for performing literature searches. Supported by a Departmental Award from Research to Prevent Blindness, NY, USA and by the Knights Templar Education Foundation of Georgia, Inc, GA, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Laser photocoagulation for juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization: five-year results from randomized clinical trials. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:500–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Argon laser photocoagulation for neovascular maculopathy after five years: results from randomized clinical trials. Arch Ophthalmol 1991;109:1109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. The influence of treatment extent on the visual acuity of eyes treated with krypton laser for juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:190–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorenson JA, Yannuzzi LA, Shakin JL. Recurrent subretinal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 1985;92:1059–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Recurrent choroidal neovascularization after argon laser photocoagulation for neovascular maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1986;104:503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Laser photocoagulation of subfoveal recurrent neovascular lesions in age-related macular degeneration: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1991;109:1232–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Persistent and recurrent neovascularization after laser photocoagulation for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:489–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treatment of Age-related Macular Degeneration with Photodynamic Therapy (TAP) study Group. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: one-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials: TAP report 1. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:1329–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verteporfin in Photodynamic Therapy Study Group. Verteporfin therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: two-year results of a randomized clinical trial including lesions with occult with no classic choroidal neovascularization: verteporfin in photodynamic therapy Report 2. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:541–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Submacular Surgery Trials Pilot Study Investigators. Submacular surgery trials randomized pilot trial for laser photocoagulation versus surgery for recurrent choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration: I. Ophthalmic Outcomes: Submacular Surgery Trials Pilot Study Report Number 1 Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:387–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spaide RF, Guyer DR, McCormick B, et al. External beam radiation therapy for choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 1998;105:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stalmans P, Leys A, Van Limbergen E. External beam radiotherapy (20 Gy, 2 Gy fractions) fails to control the growth of choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: A review of 111 cases. Retina 1997;17:481–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Postgens H, Bodanowitz S, Kroll P. Low-dose radiation therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1997;235:656–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakravarthy U, Houston RF, Archer DB. Treatment of age-related subfoveal neovascular membranes by teletherapy: A pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol 1993;77:265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freire J, Longton WA, Miyamoto CT, et al. External radiotherapy in macular degeneration: Technique and preliminary subjective response. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys 1996;36:857–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart PM, et al. Teletherapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization of age-related macular degeneration: results of follow-up in a non-randomized study. Br J Ophthalmol 1996;80:1046–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finger PT, Berson A, Sherr D, et al. Radiation therapy for subretinal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 1996;103:878–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergink GJ, Deutman AF, Van Den Broek JECM, et al. Radiation therapy for age-related subfoveal choroidal neovascular membranes. Doc Ophthalmol 1995;90:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finger PT, Berson A, Ng T, et al. Ophthalmic plaque radiotherapy for age-related macular degeneration associated with subretinal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;127:170–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yonemoto LT, Slater JD, Friedrichsen EJ. Phase I/II study of proton beam irradiation for the treatment of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: treatment techniques and preliminary results. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys 1996;36:867–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaxel CJ, Friedrichsen EJ, Smith JO, et al. Proton beam irradiation of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Eye 2000;14:155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergink GJ, Hoyng CB, van der Maazen RWM, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial on the efficacy of radiation therapy in the control of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: radiation versus observation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1998;236:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Char DH, Irvine A, Posner MD, et al. Randomized trial of radiation for age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;127:574–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valmaggia C, Ries G, Ballinari P. Radiotherapy for sub-foveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciulla TA, Danis RP, Klein SB, et al. Proton therapy for exudative age-related macular degeneration: a randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;134:905–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi H, Kobayashi K. Age-related macular degeneration: Long-term results of radiotherapy for subfoveal neovascular membranes. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:617–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart PM, Chakravarthy U, Mackenzie G, et al. Visual outcomes in the subfoveal radiotherapy study. A randomized controlled trial of teletherapy for age-related macular degneration. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Radiation Therapy for Age-related Macular Degeneration (RAD) Study Group. A prospective, randomized, double-masked trial on radiation therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration (RFtudy). Ophthalmology 1999;106:2239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus DM, Sheils WC, Johnson MH, et al. External Beam Irradiation of Subfoveal Choroidal Neovascularization Complicating Age-Related Macular Degeneration: one-year results of a prospective, double-masked, randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:171–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holz FG, Engenhart R, Bellmann C, et al. Stereotactic radiation therapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Front Radiat Ther Oncol 1997;30:238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Hollander F, Stalmans P, Van Limbergen E, et al. Retrospective study on the evolution of visual acuity after external beam radiotherapy (20 Gy, 2 Gy fractions) for subfoveal choroidal neovascular membranes in ARMD. Bull Soc Belge Ophthalmol 1998;270:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]