Abstract

Aim: To identify the value of using collagen implant in deep sclerectomy.

Methods: A prospective randomised trial of 104 eyes (104 patients) with medically uncontrolled primary and secondary open angle glaucoma. All patients had deep sclerectomy (DS), half of them with and the other half without a collagen implant (CI) sutured in the scleral bed. The main outcome measures were intraocular pressure (IOP), visual acuity, number of treatments preoperative and postoperative, and Nd:YAG goniopunctures.

Results: Mean follow up period was 44.5 (SD 21) months for the DS group and 43.9 (SD 14) months for the deep sclerectomy with a collagen implant (DSCI) group. The mean preoperative IOP was 23.3 (SD 7.2) mm Hg for the DS group and 25.6 (SD 4.9) mm Hg for the DSCI group. The mean IOP at the first postoperative day was 6.1 (SD 4.21) mm Hg for the DS group and 5.1 (SD 3.3) mm Hg for the DSCI group. At 48 months IOP was reduced by 40% (14 versus 23.3 mm Hg) for the DS group and by 50% (12.7 versus 25.6 mm Hg) for the DSCI group. Complete success rate, defined as IOP lower than 21 mm Hg without medication, was 34.6% (18/52 patients) at 48 months for the DS group, and 63.4% (33/52 patients) for the DSCI group. Qualified success rate; patients who achieved IOP below 21 mm Hg with or without medication, was 78.8% (41/52 patients) at 48 months and 94% (49/52 patients) for the DSCI group. The mean number of medications was reduced from 2.1 (SD 0.8) to 1.0 (SD 1) after DS, and was reduced from 2.2 (SD 0.7) to 0.4 (SD 0.6) in the DSCI group (p = 0.001)

Conclusion: The use of a collagen implant in DS enhances the success rates and lowers the need for postoperative medication.

Keywords: deep sclerectomy, collagen, glaucoma, surgery

Deep sclerectomy (DS) is a non-penetrating filtration procedure for the surgical treatment of medically uncontrolled open angle glaucoma. The more classic trabeculectomy, with or without antimetabolites, has a well documented complication rate.1–12 Deep sclerectomy was designed in an attempt to lower the risk of incidence of such complications, thus offering both surgeon and patient a safer, more convenient option.13,14

Implants have been used in deep sclerectomy, in the hope of increasing the success rates of this surgery, and although a lot of studies have been published reporting on the success rates of the use of these implants,14–21 unfortunately, very few studies compared the success rates of deep sclerectomy with an implant to deep sclerectomy without an implant.22

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Case selection

In all, 104 eyes of 104 patients with medically uncontrolled primary and secondary open angle glaucoma were selected consecutively and randomly assigned (random figure tables were used) (table 1). The study patients were enrolled after the approval of the ethics committee of the University of Lausanne. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients selected were all medically uncontrolled with maximal medical therapy. Uncontrolled glaucoma was defined as uncontrolled intraocular pressure (IOP) (>21 mm Hg) measured with a Goldmann applanation tonometer under maximal tolerable medical treatment and with well documented progression of visual field defects and optic nerve morphology.

Table 1.

Demographics

| DS | DSCI | |

| Number of patients | 52 | 52 |

| Number of eyes | 52 | 52 |

| Females | 25 | 26 |

| Age | 71.6 (SD 11.7) | 72.3 (SD 11.9) |

| White race | 52 | 52 |

| Preoperative IOP | 22.9 | 25.6 |

| Preoperative visual acuity | 0.68 | 0.66 |

| Number of glaucoma medications | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Primary open angle glaucoma | 25 | 27 |

| Pseudoexfoliative glaucoma | 18 | 11 |

| Pseudophakic glaucoma | 6 | 10 |

| Normal tension glaucoma | 2 | 1 |

| Pigmentary glaucoma | 1 | 2 |

| Uveitic glaucoma | 0 | 1 |

DS = deep sclerectomy without a collagen implant; DSCI = deep sclerectomy with a collagen implant.

Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate, known allergy to collagen, advanced lens opacities, previous laser trabeculoplasty, and previous eye surgery less than 6 months before enrolment in this study.

Data recorded preoperatively

On the day before surgery, patients underwent best corrected visual acuity assessment (Snellen chart at 5 metres). IOP was measured using a Goldmann applanation tonometer mounted on a slit lamp. Patients also underwent biomicroscopy, gonioscopy, visual field testing using the G1 program of the Octopus 101, and fundus biomicroscopy.

Postoperative follow up

After surgery, all the previously mentioned examinations, except for visual field assessment, were conducted on the first and the seventh day as well as in 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 48, 54, 60, and 66 months. Visual field examination was repeated every 6 months.

Complications have been defined as follows. Hyphaema was considered present when erythrocytes were seen in the anterior chamber. Hypotony was defined as a postoperative IOP ⩽4 mm Hg for more than 2 weeks. Anterior chamber depth was clinically assessed in comparison with the fellow eye. Anterior chamber was considered shallow when there was an irido-corneal touch in the periphery, and flat when there was a lens corneal touch, as seen on biomicroscopy. Anterior chamber inflammation was considered to be present when flare could be seen by biomicroscopy. Choroidal detachment was considered present when seen in the peripheral retina, using an indirect ophthalmoscope. In the postoperative follow up, cataract was either observed as a direct consequence of filtration surgery, and termed “surgery related cataract,” or appeared progressively and has therefore been called “cataract progression.” Surgery related cataract has been defined by a rapid decrease (over a period of 1 month) of visual acuity and mainly the development of cortical opacity, whereas cataract progression has been defined as slow progressive decrease in visual acuity of more than two lines (Snellen chart) due to lens opacification, mainly nuclear sclerosis.

Statistical analysis

Results were analysed using the Student’s t test for comparison of means, χ2 analysis for 2×2 tables, Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and log rank test for long term success rate analysis. For comparison between groups the Wilcoxon test was used. Statistical software JMP version 4.0 (SAS institute Inc) as well as Excel 2000 (Microsoft) were used for all automated statistical analysis.

Surgical procedure

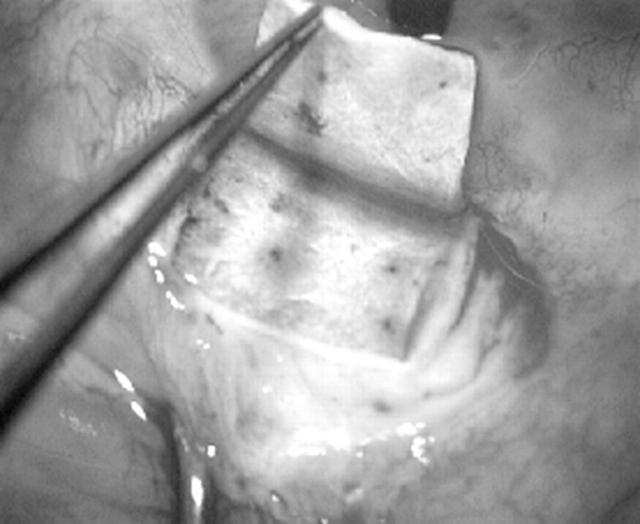

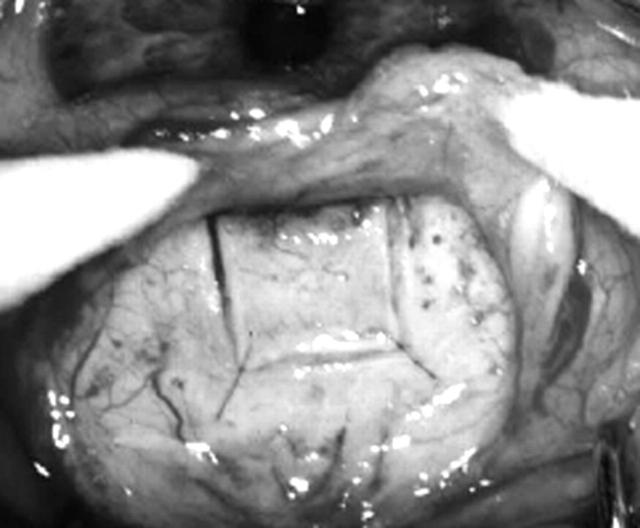

A one third scleral thickness scleral flap measuring 5×5 mm was dissected and extended 1 mm into clear cornea (fig 1). A rectangle 4×4 mm of deep sclera was then removed (fig 2). Anteriorly, the dissection was done reaching the Schlemm’s canal, which was unroofed. Moreover, anteriorly, the excision of corneal stroma was done to the level of the Descemet’s membrane. At this stage of the procedure, aqueous humour was seen to percolate through the remaining thin trabeculo-Descemet’s membrane (TDM). The collagen implant drainage device was then placed radially (fig 3), in the centre of the deep sclerectomy dissection and secured with a single 10-0 Nylon suture. The superficial scleral flap was repositioned and secured with two single 10-0 Nylon sutures (fig 4).

Figure 1.

One third 5×5 scleral thickness flap is dissected.

Figure 2.

4×4 Deep scleral flap is dissected and excised unroofing Schlemm’s canal.

Figure 3.

The collagen implant is sutured in the scleral bed.

Figure 4.

The superficial flap is repositioned, loosely tied, and the conjunctiva and Tenon are closed.

Surgery was considered a complete success when IOP was ⩽21 mm Hg without glaucoma medication and a qualified success when IOP was ⩽21 mm Hg with or without glaucoma medication. It was considered a failure when IOP was >21 mm Hg with or without glaucoma medication, or when an eye required further glaucoma drainage surgery, developed phthisis bulbi, or lost light perception.

When the filtering bleb at any postoperative visit was encysted or showed signs of fibrosis, subconjunctival injections of 5 mg of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) were administered in the lower quadrant, opposite the deep sclerectomy site. The subconjunctival injections consisted of 0.1 ml of a 50 mg/ml solution of 5-FU (250 mg/5 ml of 5-fluorouracil, Roche, Basle, Switzerland).

Goniopuncture with the Nd:YAG laser was performed when the filtration through the TDM was suspected to be insufficient, either because of a shallow filtration bleb or elevated IOP. Laser goniopuncture was considered a success when final IOP was <18 mm Hg, or when the decrease in IOP was >5 mm Hg with initial pressure of ⩽23 mm Hg.

RESULTS

The mean follow up period was 44.5 (SD 21) months for the DS group, and 43.9 (SD 14) months for the DSCI group. The mean preoperative IOP was 23.3 (SD 7.2) mm Hg for the DS group, and 25.6 (SD 4.9) mm Hg for the DSCI group. The mean IOP at the first postoperative day was 6.1 (SD 4.21) mm Hg for the DS group, and 5.1 (SD 3.3) mm Hg for the DSCI group. The IOP at 3 months was reduced by 43% (13.15 v 23.3 mm Hg) for the DS group, and was reduced by 51% (12.4 v 25.6 mm Hg) for the DSCI group. At 48 months IOP was reduced by 40% (14 v 23.3 mm Hg) for the DS group, and was reduced by 50% (12.7 v 25.6 mm Hg) for the DSCI group, thus showing stability of IOP postoperatively for both groups (table 2).

Table 2.

Intraocular pressure (IOP)

| IOP | DS | DSCI | p Value |

| Preoperative | 22.90 | 25.60 | 0.06 |

| Day 1 | 5.90 | 5.17 | 0.1 |

| Week 1 | 9.30 | 7.10 | 0.05 |

| Month 1 | 15.20 | 12.00 | 0.01 |

| Month 2 | 13.88 | 11.90 | 0.02 |

| Month 3 | 13.06 | 12.04 | 0.2 |

| Month 6 | 13.66 | 13.60 | 0.4 |

| Month 9 | 13.80 | 14.10 | 0.5 |

| Month 12 | 14.00 | 14.30 | 0.3 |

| Month 18 | 14.45 | 13.11 | 0.1 |

| Month 24 | 15.10 | 12.60 | 0.04 |

| Month 30 | 13.70 | 12.50 | 0.1 |

| Month 36 | 13.40 | 12.30 | 0.1 |

| Month 48 | 13.50 | 12.70 | 0.2 |

Complete success rate, defined as IOP lower than 21 mm Hg without medication, was 34.6% (18/52 patients) at 48 months for the DS group, and 63.4% (33/52 patients) for the DSCI group. Qualified success rate was patients who achieved IOP below 21 mm Hg with or without medication, and was 78.8% (41/52 patients) at 48 months and 94% (49/52 patients) for the DSCI group. The mean number of medications per patient was reduced from 2.1 (SD 0.8) to 1.0 (SD 1) after DS, and was reduced from 2.2 (SD 0.7) to 0.4 (SD 0.6) in the DSCI group (p = 0.001).

Of the 52 eyes on which DS was performed, 11 required re-operations (trabeculectomy, DS or DSCI), or did not achieve an IOP below 21 mm Hg with or without medications, constituting 21%. Of the 52 eyes on which DSCI was performed, two required re-operations, one patient had trabeculectomy with mitomycin C and the other had DSCI constituting 4%.

Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) dropped on the first postoperative day from a mean of 0.68 (SD 0.2) preoperatively, to a mean of 0.38 (SD 0.2) for the DS group, and from 0.66 (SD 0.3) to 0.50 (SD 0.2). Visual acuity returned to preoperative levels 1 week after surgery and remained stable over the next 4 years achieving a mean BCVA of 0.56 (SD 0.2) and 0.58 (SD 0.3) at 24 months for the DS and the DSCI group respectively. At 48 months there was a mean BCVA of 0.57 (SD 0.2) and 0.55 (SD 0.3) for the DS and the DSCI group respectively.

There were no significant operative complications recorded in this series. Postoperative complications that occurred are listed (table 3). No shallow or flat anterior chamber, no bleb related endophthalmitis, and no surgery induced cataract were observed in both groups. However, nine patients (17%) in the DS group and 11 patients (21%) in the DSCI group showed a progression of pre-existing senile cataract. Injections of 5-FU were performed on 21 patients who underwent DS and 17 patients who underwent DSCI.

Table 3.

Complications

| Complications | DS | DSCI |

| Early | ||

| Hyphaema | 8 | 4 |

| Dellen | 3 | 2 |

| Hypotony | 0 | 0 |

| Seidel | 2 | 7 |

| Choroidal deatchment | 5 | 6 |

| Choroidal detachment time | 0,4 | 0,25 |

| Shallow anterior chamber | 0 | 0 |

| Late | ||

| Needling | 3 | 2 |

| Cyst | 21 | 11 |

| Cataract | 9 | 11 |

| Others | ||

| 5-FU | 20 | 17 |

| Number of injections | 2,3 | 3 |

| Mean time of injection | 1,2 | 2,17 |

Goniopuncture with Nd:YAG laser was performed on 22 patients (42%) of the DS group and 25 (48%) of the DSCI group (table 4). The mean time between DS and goniopuncture was 23 (SD 20) months versus 14.8 (SD 13) months in the DSCI group, the mean IOP before goniopuncture was 23.6 (SD 5.8) and 18.8 (SD 4.2) mm Hg for the DS and the DSCI groups, respectively. The mean IOP after goniopuncture was 17.9 (SD 10) and 10 (SD 6) mm Hg for the DS and the DSCI groups, respectively (p = 0.01).

Table 4.

Nd:YAG goniopuncture

| DS | DSCI | |

| Number | 21 | 25 |

| YAG time | 23.7 | 14.8 |

| IOP before | 23.6 | 18.8 |

| IOP after | 16.7 | 10.04 |

DISCUSSION

Most surgeons prefer to delay surgery23 because of the potential vision threatening complications of classic trabeculectomy,1–12 with or without antimetabolites. In spite of the tendency to delay surgery, it remains a very effective way of lowering IOP. Bylsma24 suggested that if the safety margin of glaucoma surgery could be increased significantly without sacrificing efficacy, surgical intervention for glaucoma might be considered earlier.

In an attempt to avoid the numerous postoperative complications of trabeculectomy, several techniques of non-perforating filtration surgery have been described. Zimmerman and co-workers25,26 reported positive results of non-penetrating trabeculectomy in phakic and aphakic patients. Stegmann et al27 were the first to describe viscocanalostomy, in which the scleral space was filled with a viscoelastic substance, and they reported complete success of 82.7% and qualified success in 89.0% of patients at 35 month follow up.

The major advantage of non-penetrating glaucoma surgery is that it prevents the sudden hypotony that occurs following trabeculectomy by creating progressive filtration of aqueous humour from the anterior chamber to the subconjunctival space, without perforation of the eye. In an experimental model, Vaudaux and Mermoud28 studied the aqueous dynamics through the remaining thin TDM, and found that the outflow resistance was low but sufficient enough to avoid the immediate postoperative complications often seen after trabeculectomy.

In an effort aimed at enhancing the success rates of non-penetrating glaucoma surgery, Kozlov and co-workers14 reported on the use of a collagen implant. This collagen implant is a crosslinked, collagen based biocompatible material made primarily from porcine scleral tissue. Dahan proposed an unabsorbable implant (unpublished data), and Stegmann et al on the other hand used high viscosity hyaluronic acid.27 Those authors reported their results, but none proved the efficacy of their implants by comparing the procedure with and without an implant.

In the available literature there is a great deficiency in studies that compare DS to DS with the use of an implant, with only one study by Sanchez and co-workers,22 which compares DS with and without a collagen implant. They have reported better complete and qualified success rates in the DSCI group. The need for postoperative glaucoma medications was significantly lower when a collagen implant was used, and they concluded that the collagen implant increases the success rate of DS and lowers the need for postoperative glaucoma medications. Unfortunately the study had a relatively low follow up period (9.7 (SD 6.5) months for DSCI and 9.0 (SD 4.8) months for DS). Our results compare favourably with Sanchez and co-workers’ study22 but with a much longer follow up. Both complete and qualified success rates were in favour of DSCI. The need for postoperative medications was significantly reduced with the use of an implant. Complication rates were quite similar with insignificant differences between the DS and the DSCI group.

Conclusion

The use of a collagen implant in DS seems to enhance the success rates and lower the need for postoperative medications. Issues concerning the mechanisms of function of the implant, and the effect of size, material, and shape of the implant on the success rates still deserve further attention.

Presented in the ARVO meeting, Ft Laudedale, Florida, USA, April, 2001.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akafo SK, Goulstine DB, Rosenthal AR. Long-term post trabeculectomy intraocular pressures. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1992;70:312–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brubaker RF, Pederson JE. Ciliochoroidal detachment. Surv Ophthalmol 1983;27:281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Ermo F, Bonomi L, Doro D. A critical analysis of the long-term results of trabeculectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 1979;88:829–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman J, Gupta M, Bunke A. Endophthalmitis after trabeculectomy. Arch Ophthalmol 1978;96:1017–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gressel MG, Parrish RK, Heuer DK. Delayed nonexpulsive suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:1757–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kao SF, Lichter PR, Musch DC. Anterior chamber depth following filtration surgery. Ophthalmic Surg 1989;20:332–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills KB. Trabeculectomy: a retrospective long-term follow-up of 444 cases. Br J Ophthalmol 1981;65:790–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molteno AC, Bosma NJ, Kittelson JM. Otago glaucoma surgery outcome study: long-term results of trabeculectomy—1976 to 1995. Ophthalmology 1999;106:1742–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruderman JM, Harbin TS Jr, Campbell DG. Postoperative suprachoroidal hemorrhage following filtration procedures. Arch Ophthalmol 1986;104:201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart WC, Shields MB. Management of anterior chamber depth after trabeculectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;106:41–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson PG, Jakeman C, Ozturk M, et al. The complications of trabeculectomy (a 20-year follow-up). Eye 1990;4 (Pt 3) :425–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaidi AA. Trabeculectomy: a review and 4-year follow-up. Br J Ophthalmol 1980;64:436–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fyodorov SN. Non penetrating deep sclerectomy in open-angle glaucoma. Eye Microsurgery 1989;2:52–5 [In Russian]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozlov VI, Bagrov SN, Anisimova SY, et al. Nonpentrating deep sclerectomy with collagen. Eye Microsurgery 1990;3:44–6 [In Russian]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiou AG, Mermoud A, Hediguer SE, et al. Ultrasound biomicroscopy of eyes undergoing deep sclerectomy with collagen implant. Br J Ophthalmol 1996;80:541–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiou AG, Mermoud A, Underdahl JP, et al. An ultrasound biomicroscopic study of eyes after deep sclerectomy with collagen implant. Ophthalmology 1998;105:746–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demailly P, Jeanteur-Lunel MN, Berkani M, et al. [Non-penetrating deep sclerectomy combined with a collagen implant in primary open-angle glaucoma. Medium-term retrospective results]. J Fr Ophtalmol 1996;19:659–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlen ME, Sanchez E, Schnyder CC, et al. Deep sclerectomy with collagen implant: medium term results. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mermoud A, Schnyder CC, Sickenberg M, et al. Comparison of deep sclerectomy with collagen implant and trabeculectomy in open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaarawy T, Karlen M, Schnyder C, et al. Five-year results of deep sclerectomy with collagen implant. J Cataract Refract Surg 2001;27:1770–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sourdille P, Santiago PY, Villain F, et al. Reticulated hyaluronic acid implant in nonperforating trabecular surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:332–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez E, Schnyder CC, Sickenberg M, et al. Deep sclerectomy: results with and without collagen implant. Int Ophthalmol 1996;20:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 4. Comparison of treatment outcomes within race. Seven-year results. Ophthalmology 1998;105:1146–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bylsma S. Nonpenetrating deep sclerectomy: collagen implant and viscocanalostomy procedures. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1999;39:103–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmerman TJ, Kooner KS, Ford VJ, et al. Effectiveness of nonpenetrating trabeculectomy in aphakic patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg 1984;15:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman TJ, Kooner KS, Ford VJ, et al. Trabeculectomy vs. nonpenetrating trabeculectomy: a retrospective study of two procedures in phakic patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg 1984;15:734–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stegmann R, Pienaar A, Miller D. Viscocanalostomy for open-angle glaucoma in black African patients. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaudaux J, Mermoud A. Aqueous dynamics after deep sclerectomy: in vitro study. Ophthalmic practice 1998;16:204–9. [Google Scholar]