Retinal arterial occlusions may be primarily or secondarily associated with low retinal arterial pressure. Based on previous ophthalmodynamometric studies1–6 the purpose of the present study is to estimate the retinal vessel pressure in patients with central retinal artery or branch retinal artery occlusions and patients with amaurosis fugax.

Case report

This prospective clinical non-interventional comparative study included nine eyes of seven patients (mean age 68.8 (SD 13.7) years) with central retinal artery occlusion (n = 1 eye), branch retinal artery occlusion (n = 2), ischaemic ophthalmopathy (n = 2), or amaurosis fugax (n = 4). An age matched control group consisted of 27 eyes of 21 subjects attending the hospital because of cataract or refractive problems. After medical pupil dilatation, a conventional Goldmann contact lens fitted with a pressure sensor mounted into the holding ring was put onto the cornea. By slightly pressing the contact lens, pressure was applied onto the globe, and the pressure when the central retinal vein or artery started to pulsate was noted. The methods applied in the study adhered to the tenets of the declaration of Helsinki. The method has already been described in detail.6

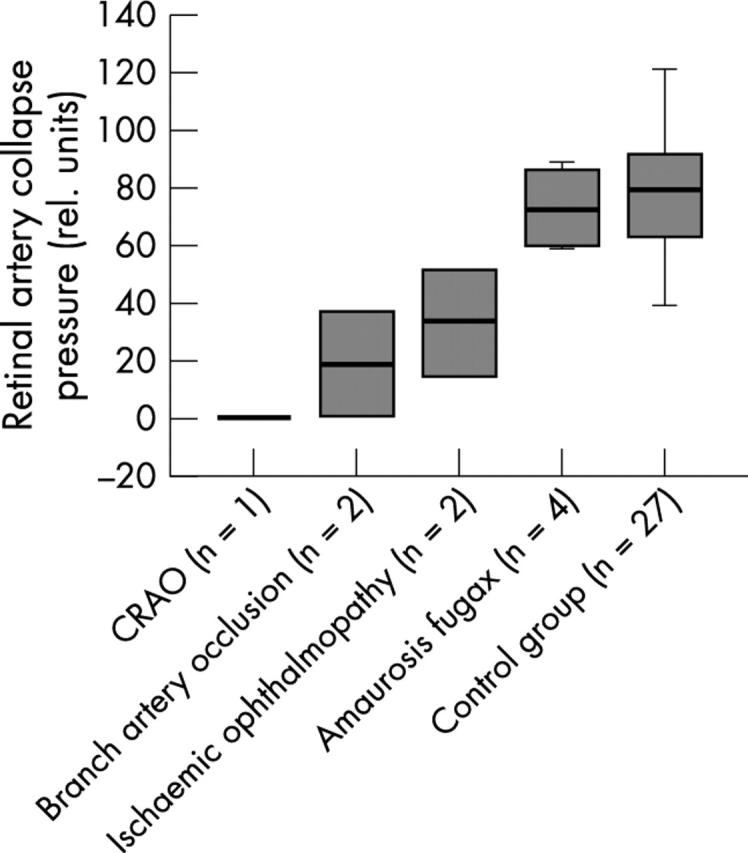

In the study group, central retinal artery collapse pressure measured 43.9 (SD 33.4) arbitrary units (AU) and was significantly (p = 0.004) lower than in the control group (78.0 (SD 19.2) AU) (fig 1). Within the study group, central retinal artery collapse pressure was lowest in the eye with central retinal artery occlusion, showing a pulse synchronic movement of the erythrocyte column in the vessel without applying any pressure onto the globe. In the two eyes with branch retinal artery occlusion, collapse pressure in the arterial branch lying in the oedematous part of the fundus measured 36.7 AU and 0 AU respectively. These values were significantly (p = 0.005) lower than the values obtained in the control group (fig 1). In the eyes with branch retinal artery occlusion, collapse pressure in the arterial branch in the non-oedematous part of the fundus was in the normal range (93.1 AU and 93.3 AU, respectively). In the patient suffering from ischaemic ophthalmopathy, central retinal artery collapse pressure was lower in the eye more severely affected than in the contralateral eye (14.7 AU v 51.7 AU). Both values were significantly (p = 0.02) lower than the values of the control group. In the eyes with amaurosis fugax, mean central retinal artery collapse pressure measured 73.0 (SD 15.4) AU which was not significantly (p = 0.55) different from central retinal artery collapse pressure in the control group (fig 1). Central retinal vein collapse pressure did not vary significantly between the study groups and the control group (8.8 (SD 12.2) AU v 6.1 (SD 8.4) AU; p = 0.54).

Figure 1.

Box plots showing the retinal artery collapse pressure in the study group of patients with central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), branch retinal artery occlusion, ischaemic ophthalmopathy, amaurosis fugax, and in the control group.

Comment

Central retinal artery collapse pressure as determined by the new ophthalmodynamometric technique was significantly lower in eyes with retinal artery occlusive diseases than in normal eyes (fig 1). Correspondingly, in the eyes with branch retinal artery occlusions, measurements were lower in the arterial branch affected by the occlusion than in the retinal artery branch with intact perfusion. As a corollary, in the patient suffering from ischaemic ophthalmopathy, the central retinal artery collapse pressure was lower in the eye more severely affected because of a complete stenosis of the carotid artery than in the contralateral eye. Interestingly, the eyes with amaurosis fugax did not show significantly lower measurements than normal eyes. This agrees with previous studies using other ophthalmodynamometric techniques for evaluation of carotid artery perfusion.4 In conclusion, using a new ophthalmodynamometer with biomicroscopic observation of central retinal vessels during the examination, central retinal artery collapse pressure measurements were significantly lower in eyes with retinal arterial occlusive diseases than in normal eyes. Future studies may show whether determination of the central retinal artery collapse pressure in patients with increased risk for retinal arterial occlusions may be suitable to predict which patients have a higher risk for eventual retinal artery occlusion compared with other patients with a similar risk profile.

Proprietary interest: none.

References

- 1.Rios-Montenegro EN, Anderson DR, David NJ. Intracranial pressure and ocular hemodynamics. Arch Ophthalmol 1973;89:52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yablonski M. A new fundus lens ophthalmodynamometer. Am J Ophthalmol 1978;86:644–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krieglstein GK, da Silva FA. Comparative measurements of the ophthalmic arterial pressure using the Mikuni dynamometer and the Stepanik-arteriotonograph. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol 1979;212:77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaret CR, Sacks JG, Holm PW. Suction ophthalmodynamometry in the diagnosis of carotid stenosis. Ophthalmology 1979;86:1510–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Entenmann B, Robert YC, Pirani P, et al. Contact lens tonometry—application in humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997;38:2447–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jonas JB. Reproducibility of ophthalmodynamometric measurements of the central retinal artery and vein collapse pressure. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87:577–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]